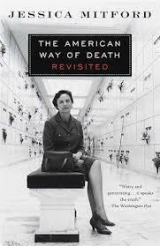

Текст книги "The American Way of Death Revisited"

Автор книги: Jessica Mitford

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

6. THE RATIONALE

A funeral service is a social function at which the deceased is the guest of honor and the center of attraction…. A poorly prepared body in a beautiful casket is just as incongruous as a young lady appearing at a party in a costly gown and with her hair in curlers.

—CLARENCE G. STRUB AND L. G. FREDERICK, The Principles and Practices of Embalming

The words “costly gown” are the operative ones in the above paragraph, culled from a standard embalming-school textbook. The same thought is often expressed by funeral men: “Certainly, the incentive to select quality merchandise would be materially lessened if the body of the deceased were not decontaminated and made presentable,” says De-Ce-Co, the publication of a funeral supply company. And Mr. T. E. Schier, president of the Settegast-Kopf Funeral Home in Houston, Texas, says, “The majority of the American people purchase caskets, not for the limited solace from their beauty prior to funeral service, or for the impression that they may create before their friends and associates. Instead, they full-heartedly believe that the casket and the vault give protection to that which has been accomplished by the embalmer.”

One might suppose—and many people do—that the whole point of embalming is the long-term preservation of the deceased. Actually, although phrases like “peace-of-mind protection” and “eternal preservation” crop up frequently in casket and vault advertising, the embalmers themselves know better. For just how long is an embalmed body preserved? The simple truth is that a body canbe preserved for a very long time indeed—probably for many years, depending upon the strength of the fluids used, and the temperature and humidity of the surrounding atmosphere. Cadavers prepared for use in anatomical research may outlast the hardiest medical student. The trouble is, they don’t look very pretty; in fact they tend to resemble old shoe leather.

The more dilute the embalming fluid, the softer and more natural-appearing the guest of honor. Therefore, the usual procedure is to embalm with about enough preservative to ensure that the body will last through the funeral—generally, a matter of a few days. “To the ancient embalmer permanent preservation was of prime importance and the maintenance of a natural color and texture a matter of minor concern; to us the creation and maintenance of a lifelike naturalness is the major objective, and post-burial preservation is incidental…. The Egyptian embalmer’s subjects have remained preserved for thousands of years—while the modern embalmer sometimes has to pray for favorable climatic conditions to help him maintain satisfactory preservation for a couple of days.” The same textbook, The Principles and Practices of Embalming, cautioning the neophyte embalmer on the danger of trying to get by with inadequate embalming, says, “But if we were to approach the average embalmer and tell him that the body he had just embalmed would have to be kept on display for a month or two during the summer, what would his reaction be? To fall in a dead faint from fright, no doubt.”

No matter what the more gullible customers may be led to believe about eternal preservation in the privacy of the arrangements-room conference, undertakers do not try to mislead the serious investigator about this. They will generally admit quite readily that their handiwork is not even intended to be permanent.

If long-term preservation is not the embalmer’s objective, what then is?

Clearly, some rather solid-sounding justifications for the procedure had to be advanced, above and beyond the fact that embalming is good business for the undertaker because it helps him to sell more expensive caskets.

The two grounds chosen by the undertaking trade for defense of embalming embrace two objectives near and dear to the hearts of Americans: hygiene, and mental health. The theory that embalming is an essential hygienic measure has long been advanced by the funeral industry. A much newer concept, that embalming and restoring the deceased are necessary for the mental well-being of the survivors, is now being promoted by industry leaders; the observer who looks closely will discover a myth in the making here. “Grief therapy,” the official name bestowed by the undertakers on this aspect of their work, has long been a second line of defense for the embalmers.

The primary purpose of embalming, all funeral men will tell you, is a sanitary one, the disinfecting of the body so that it is no longer a health menace. More than one writer, soaring to wonderful heights of fantasy, has gone so far as to attribute the falling death rate in this century to the practice of embalming (which, if true, would seem a little shortsighted on the part of the practitioners): “It is a significant fact that when embalming was in its infancy, the death rate was 21 to every 1,000 persons per year, and today it has been reduced to 10 to every 1,000 per year.” The writer magnanimously bestows “a great deal of credit” for this on the medical profession, adding that funeral directors are responsible for “about 50 percent of this wonderful work of sanitation which has so materially lowered the death rate.” When embalmers get together to talk among themselves, they are more realistic about the wonderful work of sanitation. In a panel discussion reported by the National Funeral Service Journal, Dr. I. M. Feinberg, an instructor at the Worsham College of Mortuary Science, said, “Sanitation is probably the farthest thing from the mind of the modern embalmer. We must realize that the motives for embalming at the present time are economic and sentimental, with a slight religious overtone.”

Whether or not the undertakers themselves actually believe that embalming fulfills an important health function (and there is evidence that most of them really do believe it), they have been extraordinarily successful in convincing the public that it does. Outside of medical circles, people who are otherwise reasonably knowledgeable and sophisticated take for granted not only that embalming is done for reasons of sanitation but that it is required by law.

In an effort to sift fact from fiction and to get an objective opinion on the matter, I sought out Dr. Jesse Carr, chief of pathology at San Francisco General Hospital and professor of pathology at the University of California Medical School. I wanted to know specifically how, and to what extent, and in what circumstances, an unembalmed cadaver poses a health threat to the living.

Dr. Carr’s office is on the third floor of the San Francisco General Hospital, its atmosphere of rationality and scientific method in refreshing contrast to that of the funeral homes. To my question “Are undertakers, in their capacity of embalmers, guardians of the public health?” Dr. Carr’s answer was short and to the point: “They are not guardians of anything except their pocketbooks. Public health virtues of embalming? You can write it off as inapplicable to our present-day conditions.” Discussing possible injury to health caused by the presence of a dead body, Dr. Carr explained that in cases of communicable disease, a dead body presents considerably less hazard than a live one. “There are several advantages to being dead,” he said cheerfully. “You don’t excrete, inhale, exhale, or perspire.” The body of a person who has died of a noncommunicable illness, such as heart disease or cancer, presents no hazard whatsoever, he explained. In the case of death from typhoid, cholera, plague, and other enteric infections, epidemics have been caused in the past by the spread of infection by rodents and seepage from graves into the city water supply. The old-time cemeteries and churchyards were particularly dangerous breeding grounds for these scourges. The solution, however, lies in city planning, engineering, and sanitation, rather than in embalming, for the organisms which cause disease live in the organs, the blood, and the bowel, and cannot all be killed by the embalming process. Thus was toppled—for me, at least—the last stronghold of the embalmers; for until then I had confidently believed that their work had value, at least in the rare cases where death is caused by such diseases.

Dr. Carr has carried on his own campaign for a decent, commonsense approach to cadavers. The morgue in his hospital was formerly a dark retreat in the basement, “supposedly for aesthetic and health reasons; people think bodies smell and are unhealthy to have around.” Objecting strongly to this, Dr. Carr had the autopsy rooms moved up to the third floor along with the offices. “The bodies aren’t smelly, they’re not dirty—bloody, of course, but that’s a normal part of medical life,” he said crisply. “We have so little apprehension of disease being spread by dead bodies that we have them up here right among us. It is medically more efficient, and a great convenience in student teaching. Ten to twenty students attend each autopsy. No danger here!”

A body will keep, under normal conditions, for twenty-four hours unless it has been opened. Floaters, explained Dr. Carr in his commonsense way, are another matter; a person who has been in the Bay for a week or more (“shrimps at the orifices, and so forth”) will decompose more rapidly. They used to burn gunpowder in the morgue when floaters were brought in, to mask the smell, but now they put them in the Deepfreeze, and after about four hours the odor stops (because the outside of the body is frozen) and the autopsy can be performed. “A good undertaker would do his cosmetology and then freeze,” said Dr. Carr thoughtfully. “Freezing is modern and sensible.”

Anxious that we not drift back to the subject of the floaters, I asked about the efficacy of embalming as a means of preservation. Even if it is very well done, he said, few cadavers embalmed for the funeral (as distinct from those embalmed for research purposes) are actually preserved.

“An exhumed embalmed body is a repugnant, moldy, foul-looking object,” said Dr. Carr emphatically. “It’s not the image of one who has been loved. You might use the quotation ‘John Brown’s body lies a-moldering in the grave’; that really sums it up. The body itself may be intact, as far as contours and so on; but the silk lining of the casket is all stained with body fluids, the wood is rotting, and the body is covered with mold.” The caskets, he said, even the solid mahogany ones that cost thousands of dollars, just disintegrate. He spoke of a case where a man was exhumed two and a half months after burial: “The casket fell apart and the body was covered with mold, long whiskers of penicillin—he looked ghastly. I’d rather be nice and rotten than covered with those whiskers of mold, although the penicillin is a pretty good preservative. Better, in fact, than embalming fluid.”

Will an embalmed corpse fare better in a sealed metal casket? Far from it. “If you seal up a casket so it is more or less airtight, you seal in the anaerobic bacteria—the kind that thrive in an airless atmosphere, you see. These are the putrefactive bacteria, and the results of their growth are pretty horrible.” He proceeded to describe them rather vividly, and added, “You’re a lot better off to be buried in an aerobic atmosphere; otherwise the putrefactive bacteria take over. In fact, you’re really better off with a shroud, and no casket at all.”

Like many another pathologist, Dr. Carr has had his run-ins with funeral directors who urge their clients to refuse to consent to postmortem medical examinations. The funeral men hate autopsies; for one thing, it does make embalming more difficult, and also they find it harder to sell the family an expensive casket if the decedent has been autopsied. There are, said Dr. Carr, three or four good concerns in San Francisco that understand and approve the reasons for postmortem examination; these will help get the needed autopsy permission from the family, and employ skilled technicians. “It’s generally the badly trained or avaricious undertaker who is resistant to the autopsy procedure. They all tip the hospital morgue men who help them, but the resistant ones are obstructive, unskilled, and can be nasty to the point of viciousness. They lie to the family, citing all sorts of horrible things that can happen to the deceased, and while they’re usually very soft-spoken with the family, they are inordinately profane with hospital superintendents and pathologists. In one case where an ear had been accidentally severed in the course of an autopsy, the mortician threatened to showit to the family.”

In a 1959 symposium in Mortuary Managementon the attitudes of funeral directors towards autopsies, some of this hostility to doctors erupts into print. One undertaker writes, “The trouble with doctors is that they think they are little tin Gods, and anything they want, we should bow to, without question. My feeling is that the business of the funeral director is to serve the family in the best way he knows how, and if the funeral director knows that an autopsy is going to work a hardship, and result in a body that would be difficult to show, or that couldn’t be shown at all, then I think the funeral director has not only the right, but the duty, to advise the family against permitting an autopsy.” Another, defending the pathologists (“After all, the medical profession as a whole is reasonably intelligent”), describes himself as a “renegade embalmer where the matter of autopsies is concerned.” He points to medical discoveries which have resulted from postmortem examination; but he evidently feels he is in a minority, for he says, “Most funeral directors are still ‘horse and buggy undertakers’ in their thinking and it shows up glaringly in their moronic attitude towards autopsies.”

To get the reaction of the funeral men to the views expressed by Dr. Carr now became my objective. I was not so much interested, at this point, in talking to the run-of-the-mill undertaker, as in talking to the leaders of the industry, those whose speeches and articles I had read in the trade press—in short, those who might be termed the theoreticians of American funeral service. They, I felt, would have at their fingertips any facts that might bolster the case for embalming, and would be in a position to speak authoritatively for the industry as a whole.

In this, I was somewhat disappointed. The discussions seemed inconclusive, and the funeral spokesmen themselves often appeared to be unclear about the points they were making.

My first interview was with Dr. Charles H. Nichols, a Ph.D. in education from Northwestern University, who became the educational director of the National Foundation of Funeral Service. Among his published works are “The Psychology of Selling Vaults” and “Selling Vaults,” which appeared in the Vault Merchandiserin 1954 and 1956 respectively. His duties at the foundation include lecturing to undertakers at the School of Management on such subjects as “Counseling in Bereavement.”

Dr. Nichols readily volunteered the information that embalming has made an enormous contribution to public health and sanitation, that if done properly it can disinfect the dead body so thoroughly that it is no longer a source of contamination. “But isa dead body a source of infection?” I asked. Dr. Nichols replied that he didn’t know. “What about foreign countries where they do not as a rule embalm; is much illness caused by failure to do so?” Dr. Nichols said he didn’t know.

Mr. Wilber Krieger was an important figure in funeral circles, for he was not only managing director of an influential trade association, National Selected Morticians, but also director of the National Foundation of Funeral Service. To my question “Why is embalming universally practiced in the United States?” he answered that there is a public health factor: germs do not die with the host, and embalming disinfects. I told him of my conversation with Dr. Jesse Carr, and of my own surprise at learning that even in typhoid cases, embalming is ineffective as a safety measure against contagion; upon which he burst out with, “That’s a typical pathologist’s answer! That’s the sort of thing you hear from so many of them.” Pressed for specific cases of illness caused by failure to embalm, Mr. Krieger recalled the death from smallpox of a prominent citizen in a small Southern community where embalming was not practiced. Hundreds went to the funeral to pay their respects, and as a result a large number of them came down with smallpox. Unfortunately, Mr. Krieger had forgotten the name of the prominent citizen, the town, and the date of this occurrence. I asked him if he would check on these details and furnish me with the facts; however, he has not yet done so.

I had no better luck in a subsequent conversation with Mr. Howard C. Raether, executive secretary of the National Funeral Directors Association (to which the great majority of funeral directors belong), and Mr. Bruce Hotchkiss, vice president of that organization and himself a practicing undertaker. In this case, our conversation was recorded on tape. I asked what health hazard is presented by a dead body which has not been opened up, for purposes of either autopsy or embalming.

MR. RAETHER: Well, as an embalmer, Bruce, aren’t there certain discharges that come from the body without it having been opened up?

MR. HOTCHKISS: Yes, most assuredly from—orally—depending upon the mode or condition preceding death.

Then I asked, “Can you give any place, then, where the public health has been endangered—give us the place and the time?”

They could not. We talked around the point for several minutes, but these two leaders of an industry built on the embalming process were unable to produce a single fact to support their major justification for the procedure. I told them what Dr. Carr had said about embalming and public health. “Do you have any comment on that?” I asked. Mr. Raether answered, “No; but we can take a look-see and try to give you some instances.”

When the results of the look-see arrived, eight weeks later, in the form of an impressive-looking document titled “Public Health and Embalming,” I was surprised to find that it was the work not of a medical expert but of Mr. Raether (who is a lawyer) himself. The approach was curiously oblique:

I confronted some teachers in colleges of mortuary science with the opinion of your San Francisco pathologist that embalming in no way lessens the spread of communicable disease. Their first reaction was “who is he, what is his proof?” And, rightly so. Then they add that it is not contended embalming destroys all microbes.

What iscontended? We are not told. An authority is cited that seems vaguely irrelevant. It is recommended that I read Public Health in Boston, 1630– 1822; I am assured that the dean of the American Academy of Funeral Service “has documented proof,” but no further evidence is offered. This reminds me of the old trial lawyers’ maxim: “When the law is against you, argue the facts; when the facts are against you, argue the law; when the law and the facts are against you, give the opposing counsel hell.”

A health officer, in the single reference to a source outside the funeral industry, is quoted as advancing a startlingly novel argument for embalming. It is efficacious, he declares, not only from a public health standpoint but “from the standpoint of man’s ages-long concern with life after death,” a proposition that is hard to argue against.

The only specific information offered Mr. Raether by spokesmen for the National Funeral Directors Association (NFDA)—to support the contention that embalming has value as a sanitary measure—concerned “the procedures followed at the famous Mayo Clinic, where they have a standing rule that no autopsy shall be conducted on a body unless that body is embalmed—unless they need tissue immediately. This is a standing rule for the protection of doctors and pathologists who might be working with the body.”

Unversed though I am in the procedures of doctors and pathologists, this sounded very strange to me. I wrote to the clinic in question to ask if it was true. Their answer: “Unfortunately, it appears that Mr. Raether has been misinformed concerning the attitude of the Mayo Clinic toward the embalming of bodies. We have no rule which requires that bodies be embalmed before an autopsy is performed. It is true that frequently bodies are embalmed prior to the performance of an autopsy, but this is done more for the convenience of the funeral directors than because of any insistence on our part.”

Kenneth V. Iserson is a professor of surgery and director of the bioethics program at the Medical School of the University of Arizona. After twenty years in practice treating dying patients and counseling professionals and families about sudden death, he realized, when preparing an ethics paper on teaching with donated remains, that there were huge gaps in his knowledge about what happened to dead bodies. He was prompted to investigate, and the results of his exploration were published as Death to Dust: What Happens to Dead Bodies?(Galen Press, 1994).

Dr. Iserson’s massive, comprehensive volume is easily the best work on the subject that has appeared in recent years, and it is written with a fluency that makes it accessible to the lay reader as well as the professional.

He was initially stymied by what he felt was a cover-up by a funeral industry that systematically conceals its methods. He says now, in words which have a familiar ring to me, “At the time I was writing, I had to work with several Deep Throats.”

Like Dr. Carr, Dr. Iserson has no patience with the argument that embalming is necessary because of the health hazard posed by unembalmed bodies. He quotes with approval Dr. Carr’s discussion with me, adding that the Arizona Auditor General’s Office, in a review of funeral industry practices, concluded that “the public health risks associated with the disposal of human remains are minimal”; also, a Canadian health minister, “Embalming serves no useful purpose in preventing the transmission of communicable disease.”

The clincher for Dr. Iserson is the acknowledged failure of embalmers universally to apply measures for their own protection. If embalmers are not concerned about protecting themselves, he reasons, what message does that send to the public about the claim that embalming is necessary as a public health measure? The true purpose of embalming, he suggests, is to facilitate an open-casket funeral—with the emphasis on casket. Embalming, he suggests, is a procedure that boils down to sales and profits.

The only “authoritative” voice the industry has been able to produce in rebuttal belongs to one John Kroshus, identified only as having a connection with the University of Minnesota’s program of mortuary science. Mr. Kroshus is quoted in Funeral Monitor(April 1996) as denouncing “the book” (again a phrase familiar to me) by posing the question: “If embalming is taken out of the funeral, then viewing the body will also be lost. If viewing is lost, then the body itself will not be central to the funeral. If the body is taken out of the funeral, then what does the funeral director have to sell?”

I could not have put it better.

In a curious, perhaps inevitable, reversal, the decades spent persuading the public that embalming is a sound public health measure have come back to haunt the funeral folk. Angrily protesting new Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regulations that end the practice of dumping bodily wastes and embalming fluids down drains or in Dumpsters, one mortician, according to Mortuary Management, ridiculed the “illogic of it all.” It seems, he claims, “that waste from dead people is now deemed to be more dangerous than that which comes from the living.” He goes on to protest that not one case of infection has been reported as resulting from the longstanding practice of dumping bodily wastes and embalming fluids down sewers.

If the public health benefits of embalming are elusive, ten times more so is the role of “grief therapy,” which is fast becoming a favorite with the funeral men. Trying to pin down the meaning of this phrase is like trying to pick up quicksilver with a fork, for it apparently has no meaning outside funeral trade circles. Although it sounds like a term picked up from the vocabulary of psychiatry, psychiatrists of whom I inquired were unable to enlighten me because they had never heard of it.

“Grief therapy” is most commonly used by funeral men to describe the mental and emotional solace which, they claim, is achieved for the bereaved family as a result of being able to “view” the embalmed and restored deceased.

The total absence of authoritative sources on the subject does not stop the undertakers and their spokesmen from donning the mantle of the psychiatrist when it suits their purposes. As an embalming textbook says, “In his care of each subject the embalmer has a heavy responsibility, for his skill and interest will largely determine the degree of permanent mental trauma to be suffered by all those closely associated with the deceased.”

Lately, the meaning of “grief therapy” has been expanded to cover not only the Beautiful Memory Picture but any number of aspects of the funeral. Within the trade, it has become a catchall phrase, its meaning conveniently elastic enough to provide justification for all of its dealings and procedures. Phrases like “therapy of mourning” and “grief syndrome” trip readily from industry tongues. The most “therapeutic” funeral, it seems, is the one that conforms to their pattern, that is to say, the one arranged under circumstances guaranteeing a maximum profit.

I had a long discussion with Mr. Raether about “grief therapy,” in which I sought to know what medical or psychiatric backing he could produce to substantiate the funeral industry theory that viewing the restored and embalmed body has psychotherapeutic value. He spoke of grief and ceremony; he mentioned some clergymen of his acquaintance who thought viewing the body was a valuable experience; but no qualified psychiatric reference was forthcoming.

Eventually he referred me to an article by Stanford University professor Edmund H. Volkart which had appeared in Explorations in Social Psychiatryand which allegedly supported the proposition that “viewing” was therapeutically valuable to the bereaved. Since Professor Volkart’s article was the only authoritative published work cited by Mr. Raether, it seemed advisable to check with him. Professor Volkart, who was at the time director of Stanford’s program in medicine and the behavioral sciences, wrote to me as follows:

I know of no evidence to support the view that “public” viewing of an embalmed body is somehow “therapeutic” to the bereaved. Certainly there are no statistics known to me comparing the outcomes of such a process in the United States with the outcomes of England where public viewing is seldom done. Indeed, since the public viewing of the corpse is part and parcel of a whole complex of events surrounding funerals, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to ascertain either its therapeutic or contra-therapeutic effect.

The phrase “grief therapy” is not in common usage in psychiatry, so far as I know. That the loss of any loved object frequently leads to depressions and malfunctioning of the organism is, of course, well known; what is not well known or understood are the conditions under which some kind of intervention should be made, or even the nature of the intervention.

My general feeling is that the phenomena of grief and mourning have appeared in human life long before there were “experts” of any kind (psychiatric, clerical, etc.) and somehow most, if not all, of the bereaved managed to survive. The interesting problem to me is why it should be that so many modern Americans seem more incapable of managing loss and/or grief than other peoples, and why we have such reliance upon specialists. My own hunch is that morbid problems of grief arise only when the relevant laypersons (family members, friends, children, etc.) somehow fail to perform their normal therapeutic roles for the bereaved—or may it be that the bereaved often break down because they simply do not know how to behave under the circumstances? Very few of us, I think, would be capable of managing sustained, ambiguous situations.

Demonstrably flimsy and absurd as the justifications for universal embalming and “viewing” may have been, these patently fraudulent claims of undertakers for their product remained immune from government intervention until 1984, when the Federal Trade Commission’s funeral rules were adopted. These provided, among other things, that:

It is a deceptive act or practice for a funeral provider to:

• Represent that state or local law requires that a deceased person be embalmed when such is not the case;

• Fail to disclose that embalming is not required by law except in certain special cases.

The rule went on to provide that prior approval for embalming must be obtained from a family member.

The howls of dismay that greeted these seemingly innocuous rulings were pitiful to behold. They echoed, indeed, the eruption, five years earlier, that followed the introduction of a similar requirement at a meeting of California’s State Board of Funeral Directors and Embalmers. I had special reason to take note of it at the time, because the proposer was my husband, Bob Treuhaft, who had been appointed to the board by then governor Jerry Brown.

The proposed regulation required that a responsible party confirm that he or she understood that:

Arterial embalming requires cutting into an artery and draining the blood, which is replaced by chemical preservatives for the temporary preservation of the body while awaiting interment. I understand that embalming is not required by law.

Bud Noakes, an editor of Mortuary Management, responded emotionally in a leading editorial: