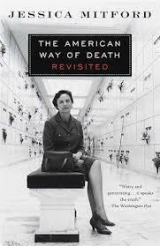

Текст книги "The American Way of Death Revisited"

Автор книги: Jessica Mitford

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

15. THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION

In 1975, after an intensive two-year study, the Federal Trade Commission’s Consumer Protection Bureau announced with much fanfare a proposed “trade rule” on funeral industry practices. The rule produced a flurry of articles in newspapers and magazines across the country, hailing it as a significant victory for consumer rights. At the heart of the original proposal were these requirements:

The Consumer’s Right to Choose. Existing industry practice was to quote a package price based on a multiple of the cost of the casket, stating that “this includes our full range of services.” The FTC rule would require itemization so that the purchaser could choose or refuse such services as embalming, use of slumber room, or grief counseling (!), with a corresponding reduction in price for unwanted items.

Prices must be quoted over the telephone. The undertakers had theretofore routinely refused to quote prices over the phone on the ground that this information was “too sensitive” to discuss by telephone. Come into my parlor, said the spider to the fly; and once there, there is little hope of escape.

Undertakers would be prohibited from misstating the law specifically with reference to embalming. They must inform the buyer that this dubious and expensive procedure (the “financial foundation of the funeral profession,” as one industry spokesman put it) is nowhere required by law. They must not tell the buyer that a casket is “required by law,” likewise untrue.

The cheapest casket must be displayed with the others. Typically, the cheapest casket would be discreetly tucked away in a closet or in the basement, where only the most persistent buyer might discover its existence.

Funeral providers would be prohibited from telling the customer that the “eternal sealer” casket will preserve the embalmed corpse for a long or indefinite time.

Arthur Angel, an FTC lawyer from 1972 to 1978 who was the main author of the rule, gave me a mini-history of its genesis. “For many years, during the fifties and sixties, the FTC had been a quiescent bureaucracy largely populated by hack lawyers from second-rate schools, and cronies recommended by politicians, mostly Southern,” he said. “This changed dramatically around 1970 or 1971 as a result of the Ralph Nader report on the FTC which roundly criticized the agency for failing to carry out its mission as watchdog in the marketplace, and the protection of consumers from abusive practices.”

It so happened that President Nixon’s son-in-law Ed Cox was a “Nader’s Raider.” He brought the report to the President, who said somewhat testily that he could not take any action on the basis of a report by Ralph Nader, but he did agree to appoint a blue-ribbon panel of American Bar Association lawyers to examine the FTC’s performance.

The panel confirmed Nader’s findings, whereupon Miles Kilpatrick, head of the panel, was appointed chairman of the FTC and its counsel, Robert Pitofsky, director of the Bureau of Consumer Protection, with the mandate to revitalize the agency.

“Beginning around 1970, and over the next four years or so, the FTC began hiring lots of new lawyers, activists from the top law schools in the country,” Angel said. “I was hired in 1972 as part of that effort.”

His description of the newcomers—“young, aggressive, disdainful of and removed from political and lobbying pressures”—was to me reminiscent of the New Dealers of the 1930s, as was the dedicated way they set about doing battle for the beleaguered consumer. First, they tried to identify especially vulnerable groups, which included the poor, the bereaved, the handicapped, the elderly. The next step was to devise projects responsive to the abuses that affected them. “One item on the list was the word ‘funerals,’ ” Angel told me. “We then read your book, Ruth Mulvey Harmer’s The High Cost of Dying, trade journals, and the like.” Out of this emerged a pilot survey of funeral prices in the District of Columbia, which led eventually to the trade-regulation rule.

To the average reader, the FTC’s proposed rule might seem mild and unobjectionable; all it sought to do was to bring the funeral transaction into line with standard fair-business practices, and to require undertakers to refrain from lying about the law concerning embalming and caskets. But the industry responded with characteristic belligerence, as to a call to arms. IT WILL BE A COSTLY WAR, declared the American Funeral Director, which described the FTC hearings as “a Soviet-style set piece staged by FTC.” The rhetoric got pretty wild. Howard C. Raether, at the time the industry’s most influential spokesman, writing in the house organ of the National Funeral Directors Association, lambasted the proposed rule as “a veiled attempt by the FTC staff to reverse the philosophy of American funeral customs, which have been historically developed within our society by the American public to effectively meet their needs when confronted by a death in the family…. There is an implication that these rules may bring about that which will be revolutionary.”

Mr. John C. Curran, past president of the New York State Funeral Directors Association, went him one better: testifying at the New York FTC hearing, he called the rule “a threat to the American way of life” and accused the FTC of “tampering with the soul of America.” The same thought was voiced in Mortuary Management:“FTC staff are trying to force their agnostic, atheistic ways on the Godfearing, traditional family-oriented America….”

As required by law, the FTC held hearings on the proposed rule in six cities across the nation, at which spokesmen for each side—consumer and industry—testified, and were then subject to cross-examination by the opposing side. I was asked to testify in favor of the rule at the hearing in Los Angeles, where, to my surprise and pleasure, the industry spokesman chosen to cross-examine me was none other than Howard C. Raether himself.

The hearing room was packed with partisans for and against: members of the Los Angeles Memorial Society, Unitarians, Quakers cheek by jowl with black-suited CEOs of the finest Los Angeles mortuaries, with plenty of press on hand to record the event. I spoke my piece, a brief rundown of how the Funeral Rule would serve to curb some of the worst excesses of undertakers, then sat back, agog for Mr. Raether’s questions.

Seeking to demonstrate that the undertaker does indeed have an obligation as “grief counselor” to guide the funeral purchaser in his choice of an aesthetically pleasing casket, he asked some hypothetical questions, and I found myself led on a merry chase into the fantasy world of the mortuary:

RAETHER: John Jones dies of a kidney disease. He is jaundiced. His wife is looking at a casket with an interior which will bring out the jaundiced condition. Should he [funeral director] suggest other caskets which would make a more aesthetic picture for the wife and members of the family?

MITFORD: Well, I like the idea of the matching casket, the jaundice-colored one. I mean, if Idied of jaundice I would rather have a jaundice-colored casket for myself. Just so with scarlet fever, I should have a red one.

There was a gratifying clatter of laughter from the pro-rule members of the audience; the black suits sat stony-faced. But Mr. Raether, not to be deterred, continued doggedly:

RAETHER: Joanna Smith is a heavy person.

MITFORD: We are all getting a little stout.

RAETHER: Her husband is looking at a casket in which the funeral director knows she will not look proper because of the size and the nature of the casket. Should he so advise the husband?

MITFORD: Well, maybe the husband is trying to guy her up a bit. Perhaps he was always saying to her, “You should go on a diet,” and now he is just getting even. Who knows?

While on the surface the outlook for successful adoption of the rule appeared bright, behind the scenes the mortuary interests were having some success. Industry leaders exhorted rank-and-file undertakers to bring pressure on their elected representatives, and were able to report occasional victories, as when Mr. Thomas H. Clark, counsel for the National Funeral Directors Association, congratulated one industry group for its lobbying efforts: “Many of you were instrumental and helpful in trying to get to the various Congressmen of the United States…. You know, we got seventy-three Congressmen and thirteen Senators who signed resolutions condemning the FTC.”

Arthur Angel and his colleagues at the Federal Trade Commission soon began to feel the impact of this activity. He told me, “By 1976 the FTC’s activism and aggressive actions against many powerful interests had galvanized escalating lobbying efforts. Lobbyists for various groups swarmed over Capitol Hill complaining about youthful zealots who were running amok and who could not be reasoned with. The FTC began to feel the pressure. To try to placate its foes, some of the FTC’s leadership began trying to moderate or weaken various projects. The attempts to weaken the Funeral Rule were part of that effort.”

By 1978 two components of the rule had already been dropped: the requirement to display the cheapest caskets with the others, and the prohibition against trying to influence the buyer in his choice of funeral. Frustrated and foreseeing correctly, as it turned out, that the rule would be further gutted, Arthur Angel resigned.

The mills of the FTC grind slowly, yet (in terms of results) exceedingly small. To those involved, the process seemed interminable—from 1973, when Arthur Angel and colleagues had begun researching the funeral industry, to announcement of the proposed trade rule in 1975, on through the public hearings to final adoption of the rule in 1984.

By 1985 it would seem that all was now in place for at least some minimal protection for the funeral buyer as provided in the rule.

However, that year I had a letter from a Mr. H., a seventy-six-year-old resident of Palo Alto, California, who was thinking about his funeral. Wishing to spare his daughter the job of arranging it, he telephoned a funeral home and asked their price for a simple cremation. About $300, said the funeral home. Mr. H.’s next step was to ask the funeral home for a written quotation. When it eventually arrived, the listed price came to $525.

Mr. H. knew all about the FTC “Funeral Rule”; he had made quite a study of it. So he wrote a letter of complaint to the San Francisco regional office. He sent me a copy of his letter together with the reply from an FTC staff member:

We have only limited resources to take formal actions against possible violators. Our actions are designed to correct those violations which affect a significant number of consumers.

That seemed to me ridiculous, for is not Mr. H. a member of the general public? And was not the funeral home’s misrepresentation exactly what the FTC rule was supposed to prevent?

My conversation with a lawyer in the same regional office, with whom I discussed this correspondence, was not reassuring. “We don’t represent individuals. This is an isolated case,” he told me. What, I asked, is considered to be “a significant number of consumers”? There is no set number, he answered. Would it be three? Six? A hundred? “I couldn’t say,” he said.

Frustrated, I telephoned FTC commissioner Patricia Bailey in Washington. She immediately saw the point; after that, things happened quickly. The director of the regional office, informed of the facts of this matter by Commissioner Bailey, promptly investigated and determined that Mr. H.’s case was “completely mishandled.” He assured me that the staff member who wrote the letter and the lawyer with whom I spoke had been “appropriately admonished.”

At the time, I thought this incident did raise some troubling questions: How many potential funeral shoppers would have the gumption of Mr. H., the tenacity to make a complaint to a government agency, and to a writer whom he had never met? Should one have to go to the expense of a phone call to Washington, D.C., to resolve the difficulty? But at least, thanks to the intervention of Commissioner Bailey, there was every reason to believe that the FTC staff members would never again treat a correspondent with a legitimate complaint in this patronizing and dismissive manner. Not so, as it turned out.

I remember once asking an editor at Lifemagazine what happens when the subject of an article complains that he or she has been misquoted, maligned, or otherwise unfairly treated by the mag. “Well, the first thing we do is to fire Murphy, and this usually satisfies the aggrieved party,” he explained. Murphy, of course, doesn’t exist except for the purpose of getting fired to placate an irate reader.

Ten years after our efforts on behalf of Mr. H., I discovered that Commissioner Bailey and I had been victims of a similar stratagem: evidently the alleged “appropriate admonishment” of some imaginary staff member was a convenient fiction adopted to shut us up.

In February 1995 I sought out Gerald Wright, the attorney responsible for enforcing the Funeral Rule in the San Francisco regional office of the FTC. What would happen today, I asked him, if an individual wrote to his office with a complaint like that of my long-ago Palo Alto correspondent? Mr. Wright produced a form letter, dated February 3, 1995, which read:

Unfortunately, we have only limited resources to take formal action against possible violators. Our actions are taken only on behalf of the general public and are designed to correct those violations which affect a significant number of consumers.

Plus ça change…

Further on enforcement, Mr. Wright told me that from 1984 to February 1995 there had been a total of thirty-eight cases “formally filed” against funeral directors; of those, only two had gone to trial. Fines imposed for violations range from $10,000 to $100,000; the average is about $30,000.

He estimated that it takes eight months to a year to finish a case. An average of a little over three cases a year for eleven years seemed very slim pickings. I asked Mr. Wright how the assignments for any given FTC project are handled—how much staff time would be allotted to enforcing the rule? Reverting to the bureaucratic idiom of his calling, he explained that the FTC employs some six hundred attorneys nationwide and three hundred economists; “about half of them will cover consumer protection measures. When you get down to enforcing the Funeral Rule, maybe two work years out of six hundred will be delegated to covering that particular rule,” but he was unable to estimate how much time he personally devoted to enforcing the Funeral Rule.

In 1990 the FTC, after a review by its Bureau of Economics Analysis, concluded—to no one’s surprise—that “the Rule has not contributed to a general reduction in the price of funerals.” By a subsequent series of capitulations to industry lobbyists, the agency has abandoned any pretense of consumer protection and has cleared the way for an era of unprecedented profitability.

In June 1994 the commission adopted an amendment to the rule to permit sellers to add their overhead to a nondeclinable fee, to cover a laundry list of items such as insurance, taxes, staff salaries, maintenance of common areas including the parking lot, and, not least, an unrestricted allowance for profit. The FTC thereby, in a single stroke, obliterated the import of itemization and the consumer’s right to choose established only a decade earlier. Package pricing, under the guise of the now FTC-endorsed nonnegotiable fee, has come back with a vengeance, and with it, for the funeral director, an exhilarating upward spiral of prices and profits.

The added fee is another device to enable the funeral seller to further confuse his already befuddled customer. In the bad old days—before there was any FTC rule and when package pricing was the norm—the consumer at least knew that the price of the casket was the cost of the entire funeral. Now, however, the standard general price list looks like this:

Pumphrey Funeral Home General Price List

| Basic services of funeral director and staff $1,525 |

| Transfer of remains to the funeral home $ 255 |

| Embalming, or $ 370 |

| No embalming, refrigeration $ 375 |

| Dressing, cosmetics, casketing $ 215 |

| Use of facilities for Viewing, per day $ 290 |

| Use of facilities for Funeral Ceremony $ 315 |

| Hearse $ 235 |

| Flower Car $ 85 |

| Sedan $ 115 |

| Limo $ 120 |

| Total for services and use of premises $3,375 |

To this must be added the cost of the casket—quoted by this mortuary in the $500 to $25,000 range—and the cost of the outside burial container or vault (required now by almost all cemeteries)—quoted range, $525 to $6,500.

The price list of the Pumphrey Funeral Home, Washington, D.C., is taken as an example because its prices fall within the middle range nationwide.

If the price of the cheapest steel casket—$2,000—is added, the funeral director’s bill comes to $5,375—exclusive of cemetery and outer container costs.

In the Houston, Texas, area, for example, the identical goods and services (cemetery and vault charges not included) can be had for as little as $1,585 or as much as $8,420.

The FTC makes no effort to ascertain whether funeral establishments are complying with the rule, Mr. Wright told me. However, in scattered parts of the country there are stalwart souls, mostly unpaid volunteers, who for some reason—often a firsthand run-in with an undertaker—have become obsessed with righting the wrongs inflicted by the industry. Such a one is Lisa Carlson, longtime consumer advocate on funeral issues and active in the nonprofit Vermont Memorial Society.

Vermont, with about five thousand deaths a year, is blessed or afflicted—depending on one’s point of view—with seventy funeral homes to handle these, meaning that each “home” averages just under 1.4 customers a week. In 1994 Lisa Carlson conducted a price survey covering 87 percent of the state’s funeral establishments: she found that nonewere in full compliance with the FTC’s Funeral Rule. After the FTC announced its new watered-down rules, the price situation deteriorated fast. In 1995 Ms. Carlson wrote a furious letter to the FTC saying that “the changes have left consumers at serious risk” and had “effectively gutted consumer protection,” since the new Funeral Rule now permits “bundling” of charges that the original rule had banned. Statewide, the already bloated nondeclinable fee had increased 28 percent in the year after the rule was amended. She cited the case of a Swanton woman whose mother’s funeral in 1993 cost $2,900. When her father died in June 1995, the identical funeral was billed at $7,100.

Five months after Gerald Wright had assured me that the FTC makes no systematic effort to discover whether funeral establishments are complying with the rule, suddenly—surprise, surprise—on July 6, 1995, the FTC came out with guns ablazing in the form of a press release headlined NATIONWIDE CRACKDOWN ON FUNERAL HOMES THAT FAIL TO PROVIDE REQUIRED CUSTOMER INFORMATION LAUNCHED BY FTC WITH STATE ATTORNEYS GENERAL. Jodie Bernstein, director of the FTC’s Bureau of Consumer Protection, is quoted as saying that “the Commission has joined forces with state Attorneys General to switch from targeting violators based on complaints to a proactive approach designed to send a no-tolerance message and follow it up with quick and sure enforcement action.”

The proactive approach, it develops, was to send “test shoppers into funeral homes in a given area to determine whether the homes provide consumers with copies of itemized price lists.” This, of course, is precisely what Lisa Carlson and memorial society colleagues around the country had been doing for years while the FTC was soundly sleeping (in fact, of the thirty-eight actions against violators resulting in fines since promulgation of the Funeral Rule fourteen years ago, over half had been turned in by members of the consumer funeral watchdog group).

So far so good, although when one reads further it turns out that the crackdown wasn’t all that nationwide, since it involved only seven of Tennessee’s 436 funeral homes, all in Nashville; nor was it all that much of a crackdown, as only three were fined, ranging from a measly $4,000 to $16,000—sums that could handily be recouped by the funeral homes from the profits of a funeral or two.

For the next six months the FTC, perhaps exhausted from its efforts in Tennessee, lay low and said nothing. On January 16, 1996, there came another press release stating that five of Florida’s 794 funeral homes—all in Tampa—were the latest to be identified in the FTC’s response to low compliance: a nationwide “crackdown.” Four of these received fines ranging from $4,000 to $35,000; one escaped any penalty by pleading poverty. The next episode in the great nationwide crackdown came shortly thereafter, when the FTC announced a “sweep” conducted in the Delaware area. This netted five violators, four of whom were fined from $3,200 to $7,700, and the fifth again let off because of the defendant’s “financial situation.”

This, then, was the sum total of the “nationwide crackdown,” which in the course of a full year had managed to miss forty-seven states altogether, had discovered no more than seventeen of the nation’s funeral homes in violation (although the FTC had reported in 1990 that less than 30 percent of all mortuaries nationwide were in compliance), and had recovered a total of $104,000 in fines.

The question remains: Why, after years of inactivity, was the “nationwide crackdown” suddenly announced in 1995? Whose idea was it?

According to Tom Cohn, one of the FTC lawyers in charge of the “sweeps,” these questions cannot be answered: “That is not public information,” he said. One could, of course, speculate that somebody—or bodies—in the FTC had begun to feel a wee bit nervous about renewed public scrutiny: Lisa Carlson and her assiduous surveys; parallel activity in many parts of the country by other consumer advocates; a documentary about funerals on “20/20”; my interview with Gerald Wright, plus numerous calls to the FTC by Karen Leonard, my persistent research assistant….

Was the FTC’s tepid burst of activity intended to assure Congress and the consumer watchdogs generally that the commission was in the arena protecting the public interest? Or was it nothing more than a maneuver to distract attention from the agency’s shameful failure to take even a single step to curb the fraud and criminal misconduct that have become endemic in an industry engaged in fixing prices at ever higher levels and profiteering at the expense of bereaved families, and that has misappropriated hundreds of millions of dollars in funds entrusted for prepayment of funerals and cemetery property?

Here, for once, was government action which produced no outcry from the industry. The reason became clear when the Funeral Monitor, a privately circulated offshoot of Mortuary Management, in its January 29, 1996, issue reported:

NATIONAL FUNERAL DIRECTORS ASSN. AND FTC STRIKE UP A DEAL:

Funeral professionals will be pleased to know that the only national organization with the size and clout to make a deal with the federal government has negotiated a bold and innovative agreement regarding enforcement of the Funeral Rule. The old confrontational enforcement approach wasn’t a notable success, so somebody said let’s try something new.

Apparently that somebody was none other than the NFDA itself, for an FTC release of January 19, 1996, announcing the plan, says:

The programs were developed by the National Funeral Directors Association and will be implemented jointly by the NFDA and the FTC…. [T]hrough these programs, the funeral industry will be working together with the FTC in a committed way to resolve low compliance with the Rule’s price disclosure requirements.

Under the new plan, no longer will funeral homes be subject to a fine for violating the rule. The FTC release states that “funeral homes that failed to give test shoppers the general price lists may have the option to enter the Funeral Rule Offenders Program. Under the program, the funeral home will make a voluntary payment to the U.S. Treasury that is lower than the civil penalty the FTC can obtain for Rule violations…. Funeral home participants will benefit from reduced legal fees, reduced and tax-deductible payments to the Treasury, and free training.”

So much for the FTC’s official concession. The Funeral Monitor’s account is a far better read, and it includes some significant items omitted from the FTC’s announcement for public consumption. Here we learn that

specifics of the FTC offenders program include: The FTC will no longer publicize the names of funeral homes accused of violating the rule. Funeral homes which violate the rule will be able to avoid a complaint filed in federal court, as well as an injunction against the funeral home and owner. And to top it off, violators will receive an emblem telling consumers that the establishment is a program participant and has voluntarily agreed to comply with the provisions of the Funeral Rule.

No wonder that NFDA executive director Robert Harden exultantly told the Monitor, “These programs create a win-win situation!”

But will the FTC be able to assure the anonymity of its favored offenders—known now only as “FROPees”—under its Funeral Rule Offenders Program? Not if the ever-troublesome band of “Memorialites”—as one industry writer has dubbed them—has its way. Exercising rights under the Freedom of Information Act to obtain the names of FROPees, the Funeral and Memorial Societies of America (FAMSA) is posting the names of offending funeral homes on its Web site: www.funerals.org/famsa/frop.htm.

But that is a small gesture compared with the current goal of FAMSA—the umbrella organization for the 125 nonprofit funeral and memorial societies in the U.S.—which is nothing less than to recast the FTC rule altogether to make it truly, in the FTC’s own words, “proactive” on behalf of the long-neglected consumer. High on the list of changes being sought are elimination of the nondeclinable fee and bringing cemeteries under coverage of the rule.