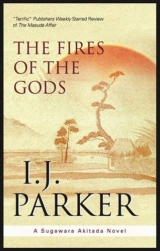

Текст книги "The Fires of the Gods"

Автор книги: Ingrid J. Parker

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

‘No. Apparently Kiyowara’s head was bashed in. I did wonder what a man of Atsunori’s rank was doing there.’

‘Yes, it’s strange.’

‘I also saw another famous gentleman. Ono Takamura was coming from the women’s quarters.’

‘The poet? He’s a favorite of the court at the moment. They say the collection he’s working on will be brilliant. A lot of people hope to be included.’ Nakatoshi pondered a moment, then said, ‘I would have thought him harmless. All he cares about is poetry and his comforts. He makes himself pleasant to people in power because they supply him with praise and luxurious surroundings. Did you know that he lives as a guest in the Crown Prince’s Palace?’

‘Does he really? I had much the same impression of the man, but I think I must try to talk to him. He may know something about other visitors that day. How does he come to be acquainted with Kiyowara’s wives?’

‘I don’t know, sir. Perhaps I can find out.’

‘Better not.’ Akitada rose. ‘Thank you, Nakatoshi. Please don’t mention this to anyone – for your sake as well as mine.’

Nakatoshi stood also. ‘Of course. But I wonder if it might not be better if I asked the questions. It’s easier for me to get access to some of the people close to Kiyowara. Won’t you let me help, sir?’

Akitada knew what he meant. Doors would be closed to him in too many quarters now. Nobody wanted to be seen to associate with those in disfavor. He smiled at Nakatoshi. ‘Not quite yet,’ he said. ‘Perhaps later.’ But he knew he would not involve this very nice young man in his troubles.

‘Be careful, sir.’

‘I’ll try to be, Nakatoshi. My best wishes to your wife.’

Nakatoshi blushed and smiled. ‘And mine to yours, sir.’

THE COURT POET

Ono’s reputation might have entitled him to quarters in a palace, but his room lacked the luxuries Kiyowara had enjoyed.

When Akitada was shown in by a palace servant, he found a somewhat mean space dominated by a small, old desk and shelving overflowing with books, scrolls, and document boxes. But the writing set on the desk was new and very beautiful. Boxes, brush holders, water containers, seals, and even the brushes were lacquered the color of autumn maples and heavily decorated with golden leaves and mother-of-pearl flowers.

Ono himself wore a casual green silk robe open over a heavy white under-robe and brilliant red trousers. This effeminate attire suited him, as did the lassitude with which he gestured towards a cushion, saying, ‘You find me hard at work, Sugawara. Please forgive the lack of amenities. When there are fires every day, one does not want to burden oneself with possessions. Alas, I cannot even offer you wine. I do not take my meals here, and my servant has gone out for ink.’

Akitada sat down. ‘Don’t concern yourself, sir. It’s very good of you to see me.’ On closer inspection, Ono was not only a handsome man, but also older than Akitada had thought. His hair, now that he was bare-headed, was turning quite gray, though the eyes were still large and bright and his face smooth. ‘I wonder,’ Akitada asked, ‘if you recall our meeting at Kiyowara’s house two days ago?’

Ono looked blank. Clearly, he had not recognized Akitada. But he smiled quickly and nodded. ‘Ah, yes. Of course. Poor Kiyowara. He has died, you know.’

‘Yes. The very day we met. I’m afraid he was too busy to see me.’

‘Ah.’ Ono nodded, but volunteered nothing else.

Akitada thought perhaps the poet was still confused and explained, ‘You were walking in the garden, reciting poetry. I was on the veranda of the reception room. Do you remember?’

Ono’s eyes lit up. ‘Oh, that poem. I’ve rewritten it completely. Wait a moment. Now, where did I put it?’ He stared at the shelves with their boxes and scrolls, shaking his head. ‘It’s a very great undertaking, putting together an anthology of the best poems of our time. There are so many submissions that my own work gets lost among them. Sometimes I despair.’

‘Please do not trouble on my account,’ Akitada said quickly. ‘It’s the murder of Kiyowara I came about. Being a close friend, you must have some thoughts on who could have killed him.’

‘Oh, I’m not a friend. No, not at all. I didn’t like the man. And I haven’t really thought much about his death.’

That was an astonishing and – under the circumstances – foolhardy admission. Akitada cheered up a little. The poet’s lack of common sense could turn out to be very helpful. He said, ‘Oh? I thought as a frequent visitor…’ and let his voice trail off.

Ono glowered. ‘Only of Hiroko and her children. I avoided Kiyowara. The man had neither taste nor talent. His was the soul of a bureaucrat.’

Being a bureaucrat himself, Akitada was not sure he liked this. ‘But if you consider his murder now, do you have any suspicions?’

Ono looked up at the ceiling and frowned in concentration. ‘I don’t know… there was some rumor. Some official was dismissed because Kiyowara insisted on it.’ He stared at his overflowing shelves for a moment, then shook his head. ‘No, I don’t recall exactly. Why do you ask?’

With an inward sigh of relief, Akitada accepted that Ono was simply too self-absorbed to care about those around him. Getting information from him was hopeless. He said blandly, ‘Just a matter of interest. With Kiyowara gone, there will be changes in appointments. Someone else will be put in his place. That can make for a powerful motive.’

‘You think so? In my world, men feel most strongly about love and art.’

‘In mine, ambition and greed are more common,’ Akitada said dryly. ‘I assume his son will succeed to the estates?’

This time, Ono got his drift and glared. ‘Katsumi is a very fine young man. He is devoted to his mother, who is my friend. I’ve known her and her son since both were children. I will not have anyone spread slanderous lies about them.’

Akitada raised his hands. ‘Forgive me. I put it badly. As I said, I know nothing of the family.’ He wondered if Ono was truly naive or so full of his own importance that he saw no need to hide his own motive or his relationship with another man’s wife. ‘I take it that the lady has influence at court on her own account?’

Ono was still irritated. He snapped, ‘Naturally. Kiyowara owed his position to her. The Minamoto daughters were raised to be great ladies, perhaps empresses. Their education and refinement are superb. Her sister is married to Yorimichi.’

Meddling in the affairs of the kuge, those of the highest rank in the nation, was like playing with fire, and Ono clearly considered his continued interest offensive. Akitada changed the subject. ‘Speaking of Lord Yorimichi, is he aware of the rumors about the rash of fires in the city?’

The poet relaxed a little. ‘Dear heavens, yes. They said the Biwa mansion would burn. Michinaga’s daughter and grandson, the retired emperor, reside there. Both Michinaga and Yorimichi went to touch their heads to the ground before the Buddha and prayed for rain. Well, there was a big fire, and then there was rain. They saved most of the palace. It is clear that the gods inspired the rumors.’ There was a pause, during which Ono stared at Akitada. ‘Fire,’ he said after a moment. ‘Now that you mention it, fire has great poetic possibilities. My own ancestress, Komachi, wrote that she was consumed by the fire of her passion. So powerful.’ His eyes grew distant. ‘I must discuss fire with Hiroko’s cousin Aoi. Yes, the sacred fire for purification – or destruction, leaving nothing but ashes – ashes to be blown away by the winds – the winds of fate.’ He swept out an arm to describe vast distances, then tapped his mouth with a forefinger and fell into an abstraction.

Akitada tried to find something to break the spell, but Ono blinked after a moment and focused on him again.

‘Umm,’ he said, ‘a very pleasant chat, my dear fellow, and so kind of you to stop by, but you can see I’m dreadfully pressed for time. You must forgive me.’

Akitada went home, not much wiser about Kiyowara’s murder and at a loss how to proceed. He changed into his old clothes and then looked in on Tamako. She was sleeping, her maid Oyuki sitting nearby sewing some tiny clothes. Seeing the small garments moved him deeply, but he was not sure if they made him happy or afraid.

He spent several hours sorting through his papers, separating ministry materials and boxing them, and looking for forgotten promises. He had never sought preferment as a reward for helping someone, but most officials relied on just that sort of thing to protect their positions or win better ones. From time to time men had thanked him, adding that he might call on them for future benefits. But he knew it was a hopeless task. He had ignored all such offers, even received some with stiff disapproval perhaps. Now that he needed help, they would claim ignorance.

Discouraged, Akitada fled outside to see if Tora was home. He found him on the small veranda behind his and Hanae’s living quarters. He was playing with his son, swinging the baby up and down as the child gurgled with laughter. Akitada’s spirits lifted.

‘Careful,’ he cried out, when the baby’s head nearly hit the roof overhang.

Tora turned, laughing and cradling his son against his chest. ‘Did you want me, sir? I just got home, and Hanae was needed in the kitchen.’

‘No, no. I came for a chat.’ Akitada sat down, dangling his feet over the edge of the veranda. ‘How Yuki has grown! He’ll surely be a big man like his father.’

Tora grinned. Holding the baby away, bare legs kicking, he looked him over proudly. ‘Better than looking like his mama. Not that it’s not very fetching in a female. Will you hold him, sir, while I get us some wine?’

The baby was bare-bottomed, but Akitada received him gladly, almost reverently. Yuki was a fine boy and a happy child. His parents doted on him. He settled the baby, pleased that he did not cry in his arms, and fell, willy-nilly, to cooing and tickling, admiring the bright eyes, the tiny, perfectly formed fingers and toes, the smiling toothless little mouth. Soon, very soon, he would hold his own son and feel a father’s pride again. There was deep joy in such brief moments – joy that would surely make up for the fears that also lurked in the corners of the mind.

Tora returned with the wine and said, ‘Wait till you hear what happened to me.’ He poured two cups, then took the baby back and set him down next to a wooden ball, a couple of smooth bamboo sticks, and a small carving of a dog.

Akitada watched the child rolling the ball back and forth and decided to buy him a toy in the market. ‘So, what have you been up to?’

‘I met Jirokichi, the Rat.’

‘No! Did you?’

‘Well, he claimed to be Jirokichi. Five young thugs were dragging him off after giving him a bad beating. I came along just in time. They thought he had gold hidden away someplace.’

‘More mischief by young ruffians. It’s becoming a city-wide problem.’

‘My thought, too. I figured the little man would be grateful and help me find the bastards that got my gold, but when I started asking questions, he clammed up and ran.’

‘Hmm. Probably afraid of retaliation.’

‘Maybe, though he’s a spunky little guy.’

‘Did you check on the fire victims?’

Tora’s face fell. ‘Yeah. The son’s not going to live either. He was delirious. About the only thing on his mind was if his father had paid some debt.’ Tora related the dying shopkeeper’s words: ‘But Father paid the money,’ and the neighbor’s comment that the old man had been a miser. ‘It’s almost as if they thought the gods punished them in some special way.’

Akitada frowned. ‘What did the cousin have to say about that?’

‘Nothing. She said he was hallucinating, but maybe he wasn’t.’

‘No, I don’t think he was. I think she’s afraid to talk because there’s a protection scheme going on. Some masterless warrior has sold his skill with the sword to tradesmen who want protection against thieves and robbers. She and the neighbor think the fire was set because they didn’t pay.’

Tora gaped at him. ‘You mean it wasn’t the gods?’

‘Of course not, though it could have been carelessness.’

Tora said eagerly, ‘Let’s go investigate it, sir, and turn the bastards in.’

‘I have my hands full, trying to clear my name. You should report this to Superintendent Kobe.’

Tora’s face fell, but it was not in his nature to be discouraged for long. ‘You’ll solve the Kiyowara murder in no time, sir. I’ll help if you need me – only, I’m not much good at chatting up the important people. I think I’ll look for Jirokichi. He’s a thief, and he knows something he doesn’t want to talk about. Maybe I can find out if there are fire setters. Then you can report it to Superintendent Kobe and the ministry, and they’ll be so pleased that they’ll beg you to come back.’

Akitada had no hope that things would work out so smoothly, but Tora’s optimism always cheered him. His eye fell on the baby. Yuki was pursuing a shiny green beetle to the edge of the veranda and was about to tumble off into the weeds below. He lunged to snatch him back to safety. ‘Let me hold him,’ he said, bouncing the baby on his knee. ‘You can’t be trusted to look after him properly.’

At that moment, there was a loud knocking at the gate, and Tora ran off to see who it was. A moment later, Akitada heard him shouting, ‘Sir? It’s a messenger for you.’

Carrying the baby, Akitada walked back to the courtyard, where he found a member of the palace guard mounted on a splendid, red-tasseled horse. The officer stared at him. ‘Are you Secretary Sugawara?’

‘Yes.’ Akitada became aware of warm moisture spreading between the baby and himself.

The guard pulled a thin rolled-up document from his tunic and handed it down. ‘No answer is expected, sir,’ he said with a sharp nod and turned his horse to trot back out into the street.

Tora closed the gate behind him and came to take his son. ‘Sorry, sir,’ he said when he saw Akitada’s robe. ‘He’s not quite housebroken yet. What is it?’

Akitada had undone the silk ties and unrolled the letter. The thick inky brush strokes swam before his eyes after the first lines. He had to force himself to go back and read the whole document again. It spelled disaster. He rolled it up again and said, ‘It’s not good, I’m afraid. I’ve been dismissed and have to hold myself ready for an investigation by the censors.’

‘The censors? I thought Kiyowara’s murder was a police matter.’

‘Officials in the imperial administration are also subject to review by the Censors’ Bureau. It’s a good rule. They make sure that officials who have committed crimes never serve in any responsible capacity in the government again.’ He did not add that such investigations usually led to exile.

He had to bear the blame for this. When you touch fire, you get burned. Far from being an absent-minded poet, Ono must have gone to report his visit, and the chancellor had acted much more quickly than even Akitada could have expected.

RAT DROPPINGS

Tora woke to the chatter of his son Yuki. The baby normally slept between his parents, but last night Tora had wanted to make love to his wife, and on such occasions they took their son into the small kitchen area and made him a bed in a large basket.

Hanae, who had been busy in the main house for the past week, was still soundly asleep. Being a considerate husband, Tora got up to make some milk gruel for the baby.

The little kitchen was still dark. Tora struck a flint and lit an oil lamp. It was unusual for Yuki to wake up before daylight. When he raised the lamp to check on his son, he saw to his amazement that Yuki seemed to be sitting on a blanket of shining gold coins. The baby squinted against the light, then crowed with laughter at the sparkling new toys.

Tora’s jaw dropped. What the devil was this? So much gold. Was it a miracle? Had the Buddha heard his bitter complaints when he had lost his winnings the other night? But there was much more here than he had lost. Tora picked up a coin and bit it. It was real. Setting down the lamp, he gathered the gold, ignoring Yuki’s wails. He counted twenty pieces. Where had they come from?

He finally picked up the baby – who was making enough noise to wake Hanae – and set him on the floor with one of the coins. Then he started the kitchen fire under the pot of gruel Hanae had prepared the night before. It was only after these chores that he turned his attention to the wet bedding in the basket. A crumpled piece of paper fluttered to the floor.

Tora snatched it up before Yuki could grasp it and flattened it out. There was writing on it – thick, poorly shaped characters – but the message was short and simple. Tora had no trouble deciphering it.

Thank you for your help. Forget about the kids.

There was no signature; instead Jirokichi had drawn a small rat.

Tora was profoundly shocked. It was not only the very large amount of gold that upset him, but also the way it had been left in his house. How had the bastard got in? And when? Had he been spying on them while they were making love? A man was not very observant at such a time. In fact, someone probably could have ripped the roof off the place, and he would not have noticed.

So, instead of gratitude, he felt a hot fury when he looked at the gold. He wanted to shove it down the little bastard’s throat.

Yuki reminded him of the gruel by whimpering. Tora hid the gold in an empty jar on the high shelf, then mixed a small amount of gruel with some cow’s milk and, taking his son on his lap, fed him his morning meal.

He decided not to tell Hanae about their night-time visitor, because it would frighten her. His master, on the other hand, must know about it right away.

As soon as Hanae joined them, yawning widely, then smiling at husband and son, he went to wash at the well, combed his hair and tied it, and put on a clean robe.

‘You look very handsome, husband,’ Hanae crooned when he came back. She came to stand on tiptoe and kiss him.

Tora briefly considered postponing his errand, but better sense won. He released Hanae regretfully and watched her take Yuki for his bath, then he scooped the gold out of the jar and hurried to the main house.

Akitada was in his study, bent over the account ledger, his face looking drawn, as if he had not slept.

‘Here,’ said Tora and deposited the two handfuls of gold coins on Akitada’s desk. ‘I found them this morning. They’re yours.’

His master regarded first the gold, then Tora. ‘Found them? Is this the gold you were robbed of?’

‘No. I suppose I earned it. It’s from Jirokichi.’ He laid the slip of paper next to the gold.

His master read the note and shook his head. ‘I can’t take this. It’s yours,’ he said, pushing the gold towards Tora. ‘Why are you so angry?’

Tora explained about the shocking intrusion into his home. ‘I was going to ram the gold down his throat, sir, but I figured you might have a need of it. For that matter, if the bastard got into our place, he may have done a bit of thieving in your house. Maybe you’d better check.’

Akitada called Seimei, and together they made a brief search of the valuables. The money box was untouched, and everything else was as it should be.

‘A clever burglar,’ said his master. ‘You may do with the gold as you see fit, but find him and see if he can help us with the fires.’

‘I thought you didn’t want to become involved in that.’

‘I have reconsidered. I may as well try to earn a living by investigating crimes.’

Tora left the gold in his master’s strongbox and went to look for Jirokichi. He started with the thief’s girlfriend.

Hoshina’s eyes narrowed when she saw him come into her wine shop. ‘Tora,’ she cried brightly. ‘You haven’t forgotten me.’ Every man in the wine shop turned to look at him.

Tora was embarrassed. The woman was almost as tall as he and nearly twice as wide. Her arms and shoulders would have done credit to any man. Besides, the hungry way she looked at him made him uncomfortable. He liked women to be dainty and a little shy.

‘Why, you’re even more handsome today,’ she trilled and sidled up close enough to stroke his chest through his blue robe.

One of the men shouted, ‘Hey, Hoshina. I want some more wine before you drag him off to have your way with him.’ The others laughed.

Tora glared around and stepped away from Hoshina. ‘I need to talk to Jirokichi,’ he told her in a low voice. ‘Where can I find him?’

She stroked his cheek. ‘Why bother with him?’ she cooed and pressed her body against his. This brought more shouts of obscenities and laughter from the audience. ‘Sit down,’ she said, pushing him. Tora sat. She blew him a kiss. ‘We’ll talk about it over a cup of wine.’ She walked away slowly, moving her hips to the hoots and whistles of the men.

So much for Jirokichi’s romance. Tora almost felt sorry for the little rat – almost, but not quite, seeing that the encounter was proving more embarrassing by the moment. Hoshina returned to more applause, with wine and freshly painted lips. She bowed to her audience, then sat down so close to Tora that their thighs touched. The other customers watched avidly.

Tora moved away a little, but she wiggled closer and whispered in his ear, ‘Bet I can make you much happier than that wife of yours.’

‘Then Jirokichi must be a lucky man,’ Tora said hoarsely and gulped some wine.

She put a hand on his thigh and let it wander higher to whistles and a bawdy request that she offer such service to all the guests. Tora had had enough. He removed her hand from his thigh, put some coppers down, and left, his face flaming. More shouts and laughter followed him out.

His failure grated. He had got nothing from the disgusting woman, and that was not like him. Perhaps marriage had ruined his style. In the old days, he would have made up to her and taken her to bed. She was crude, but that large body was voluptuous and promised a good lay, and she would have ended up telling him whatever he wanted to know.

A sudden suspicion gave him pause. Had she performed that flagrant and very public bit of seduction to drive him away because she did not want to answer questions about Jirokichi?

Tora glowered and clenched his fists. He had expected to find Jirokichi quite easily and was wearing his ordinary clothes. The trouble was that they marked him as a retainer belonging to the household of an official. And that meant he would get no information on the whereabouts of a thief.

He wandered aimlessly around the Western Market in hopes of seeing Jirokichi on his way to Hoshina. It was a waste of time, but when he passed the vegetable sellers, he encountered the handsome youth he had seen outside Hoshina’s wine shop the day before. The boy was haggling over a daikon radish and a small cabbage.

Tora gave him a nod and a grin. Being caught by another male at such an embarrassingly feminine activity made the boy flush and turn his head away.