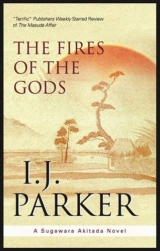

Текст книги "The Fires of the Gods"

Автор книги: Ingrid J. Parker

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

KOBE

Genba asked anxiously, ‘Sir? Sir, are you all right?’ Sitting up with Genba’s assistance, Akitada took a ragged breath. His throat still hurt from the near drowning and the gritty filth he had swallowed along with the water. His body also hurt, particularly his bad knee, but he shook his head, as much in wonder that he was still alive as to deny any injuries. ‘Tired,’ he croaked, then raised an arm to point at the constables. ‘What… brought them?’

‘When you didn’t come home by dark last night, Tora got very upset and tried to get up to go look for you…’

‘Tora – how is he?’

‘Better. The fever is coming down, but Seimei wouldn’t let him get up.’ Genba grinned. ‘No need. I was there by then. And by the way, congratulations on your new daughter. She’s a beautiful child. A princess.’

Relief and a tentative joy washed over Akitada. He was alive, and so was his family. Nothing else mattered. He tried a smile. ‘Yes, yes. Thank you. And thank you for saving my life.’

Genba gave a rumbling chuckle. ‘I did little enough, sir. It was all Superintendent Kobe’s doing. And he and I just followed Tora’s directions.’

‘Kobe? You went to Kobe?’

‘Yes, sir. Tora did say you wouldn’t like it, but I could see I would need help.’

Akitada digested that. The amazing thing was that Kobe had agreed to help. But perhaps he had been more interested in catching the gang. Sitting in the drizzle on the wet ground, Akitada considered the situation while idly picking mud from under his finger nails. Genba shuffled and cleared his throat.

Akitada looked up. ‘Oh. You did right. I owe my life to all of you.’ For the first time, he looked at his surroundings. It was still only half light, but he recognized the outline of the abandoned warehouse.

He rose unsteadily and took a few steps towards the gaggle of policemen. They were wet and had tired faces, but they grinned. Though perhaps it was his muddy appearance they found amusing.

Akitada called out, ‘Thank you. That was excellent work.’

A dry voice said, ‘Was it? It seems to me they had a very easy time of it.’

Akitada turned.

Kobe looked as wet and tired as his men. His eyes widened. ‘You look terrible,’ he said. ‘Where were you?’

Akitada nodded his head towards the muddy crater. ‘In there.’

Kobe stepped closer and looked. ‘The dear gods in heaven,’ he exploded.

‘They took exception to my asking questions of a young man in the Fragrant Peach.’ Akitada tried another smile. ‘Thanks for coming to the rescue.’

Kobe nodded. He looked uncomfortable and blustered a little. ‘You do wander into danger with the utmost unconcern. But that doesn’t excuse this. We’ve arrested everyone in the Fragrant Peach and sent them to jail. Time enough to get to the bottom of this in the morning. There was no young man, though, just an under-age girl.’

Akitada nodded. ‘She’s the daughter of the owner. He and two of his friends are deaf mutes. I doubt you’ll get anything out of them. She is normal and protects the young male. His name is Tojiro. He ran. They caught me when I followed him.’

Kobe frowned. ‘Was it that damned Kiyowara case again? You never would listen. See where it got you this time. I hear the censors have their claws into you because of it. And you with a new child to support.’

Akitada hung his head. ‘It was another case,’ he said wearily. ‘I was trying to earn money I had already spent. A question of honor rather than stubbornness.’

Kobe was not to be distracted from his lecture by mere ideals. ‘Whatever it was, the risk was too great to follow your usual obsession with solving a puzzle. Your duty is to your family first. If you needed money, all you had to do was ask me.’

The accusation was unfair, but Akitada felt tears come into his eyes at the offer of money. He was glad the light was still faint and his face was wet from rain. He was too tired for this. Hiding his emotion, he said, ‘Perhaps you’d better dismiss your men. You don’t need witnesses to read me a lecture on duty.’

Kobe muttered an apology and turned to the policemen. ‘What are you standing around for, you dolts? Get on with it. Dismissed.’ The men bowed and shuffled off.

Turning back to Akitada, Kobe said gruffly, ‘Come, we need to get you to a bathhouse.’

To Akitada’s dismay, Kobe decided to have a good soak himself. Akitada wished for nothing so much as sleep.

At this early hour, the bathing area was still empty except for a couple of attendants. They stripped. Akitada was only half awake. They sluiced themselves off, then attendants scrubbed them vigorously. This revived Akitada somewhat as his blood coursed through his body and his skin tingled. When they finally submerged their bodies in the large tub of steaming water, Akitada leaned back with a sigh and closed his eyes. His lacerated fingers burned at first in the hot water, but the pain in his knee subsided, and his sore muscles relaxed. A greater contrast between his condition in the pit and his present bliss seemed unimaginable.

‘Don’t go to sleep – at least not yet,’ Kobe said loudly.

Akitada blinked at him through the steam. ‘What?’

‘You’re still angry with me?’

Akitada was embarrassed. ‘No.’

‘I apologize. I had to try to stop you. You were headed into deep trouble. Of course, nothing I said made a difference, but I had to try.’

Overcome by the apology, Akitada said nothing for a moment, then muttered, ‘Don’t be silly. I also said some unforgivable things.’

Kobe persisted in trying to explain his motives. ‘I was afraid that you wouldn’t consider the dangers. You never do, you know.’

‘I know you thought me foolhardy. Perhaps you even thought me a fool.’

‘Never a fool.’ Kobe sighed. ‘I expect I’ll be called in today. My dismissal is overdue.’

Akitada sat up. ‘What? Why?’

Kobe chuckled mirthlessly. ‘It seems I, too, am disobedient.’

Akitada’s disobedience went back to the very beginning of his career in government, and yet he had managed to hang on – until now. ‘How did you offend?’ he asked.

‘I think they’ll call it ‘interfering in official policy’. I insisted that your only offense was trying to solve a man’s murder.’

‘You made someone angry by helping me?’

Kobe gave him a crooked grin. ‘It was the right thing to do, so don’t feel responsible.’

Akitada stared at Kobe. Their uneasy banter had turned serious.

Kobe’s lips twitched again. ‘Don’t look so worried. If anything, you’ve done me a favor. This is my chance to retire to my family’s estate in the country. I’ll be leading the simple life. Hunting, fishing, and sitting on the veranda on a summer night to compose poems to the moon.’

‘You could always have done that.’

‘Ah, but others had expectations. My aged father wished to brag about his son in the capital. My wives liked their carriage rides to visit other ladies. My sons hoped to make brilliant careers. My servants… Well, you know what servants are. They take personal pride in their masters’ worldly success.’

Akitada felt slightly sick. ‘Think how many enemies I’ve made in your household alone.’

‘Well, we must all bear the burden of our karma.’ Kobe said lightly, then changed the topic. ‘Let’s get you home.’

By the time he reached home, tiredness had seized Akitada to such an extent that he staggered. Genba had to restrain Trouble’s enthusiastic greeting. Akitada clutched the banister for a moment to steady himself. This was not good. He had to face the censors in a few hours.

Genba offered an arm, and Tora came, looking drawn and pale. Akitada was ashamed of his weakness. He pulled himself together, refused assistance, chided Tora for being out of bed, and patted Trouble’s head.

‘I’m fine, sir,’ Tora said, then added fiercely, ‘Genba told us what happened. I’ll get the bastards that did this, if it’s the last thing I do.’

Akitada wanted to protest, but Seimei joined them, looking anxious. And at the door of the house stood Tamako in her rose-colored gown, the one he liked so well, and he forgot everything else.

Though he was dreadfully tired, he found that he could walk quite well and went to her with a smile. It was not proper, but there were no strangers present, and he took his wife into his arms. For a moment, they clung to each other.

‘Are you well enough to be up?’ he murmured into her scented hair.

And she asked, ‘Are you hurt?’

They answered together, and laughed.

‘I’m just tired,’ he said, releasing her. ‘And you?’

‘Quite well, as you see.’

‘And our daughter?’

‘Come and see for yourself.’

They went to Tamako’s room, where he held his daughter until she fell asleep. He told Tamako about the pit, trying to make it sound like an adventure. The rat featured prominently in his account of their efforts at escape. It was in vain. Tamako shuddered in horror. Fortunately, the maid brought in the morning gruel, and they ate together and talked about Trouble’s latest offenses. For a short while he almost forgot the pit, as well as the dreaded hearing. But Seimei came soon enough to remind him to change into his court robes.

When he got up, Akitada found that he could barely stand. Every muscle and bone in his body, so recently soothed by the hot bath, now protested again. He gritted his teeth so Tamako would not notice, but as soon as he was out of her room, he shuffled like an old man. He had never felt less ready to fight for his reputation.

He was still struggling with his full court trousers, and trying to keep the food down, when the sound of a horse and voices outside announced a visitor. He hurried into his robe as Genba admitted the same guard officer who had brought the summons from the censors.

This time, the young man bowed. He presented a letter from Minamoto Akimoto, who told him that the hearing was postponed. He apologized for the delay, which was caused by the censors needing more time to review his documents.

The gods were not without pity.

Akitada took off his court robe and spread his bedding. He was asleep instantly.

When he woke, he blinked at the cloudy sky above the treetops and wondered what time it was.

Somewhere in the distance he heard male voices in conversation. Suddenly worried that he had slept away the whole day, he got to his feet, rolled up his bedding, and went to look for Tora, who had received short shrift earlier. After that, he would pay Kobe a visit.

He saved himself a trip. Kobe and Tora sat on the front veranda, chatting amiably.

‘I’m afraid I fell asleep,’ Akitada said sheepishly. Kobe looked as tired as before.

They smiled at him. Kobe said, ‘Seimei refused to wake you, and Tora came to keep me company. They look after you well.’

Akitada sat down beside them. ‘Yes. Too well. I meant to come to see both of you.’ He rubbed a hand over his face and found stubble. ‘What time is it?’

Kobe peered at the sky. ‘Probably the first quarter of the hour of the horse.’

‘So late,’ muttered Akitada, remembering at the same time his duties as a host. ‘It’s time for the midday meal. I hope you’ll share my simple meal.’

Kobe nodded. ‘Thank you. Tora and I were quite finished discussing his adventure when you came. You have nothing to add, do you, Tora?’

Tora shook his head. ‘Only to say again that I don’t think Jirokichi’s involved. I think he stumbled on the arson by accident.’

‘Perhaps,’ Kobe said. ‘We must find the fellow. I’ll have his girlfriend brought in.’

‘She promised to talk to me,’ Akitada said. ‘I never got back.’

Tora said, ‘You must’ve laid it on thick, sir. She wouldn’t give me so much as a comment on the weather when I talked to her.’

‘I told her you were at death’s door after saving this Jirokichi’s miserable life.’

Tora snorted. ‘Well, I’d better go feed my son.’ He bowed to Kobe and walked away. Akitada was relieved that he looked much better.

He and Kobe went to Akitada’s study, where Seimei waited with a tray holding wine and cups. ‘Will you want refreshments, sir?’ he asked Akitada.

‘The superintendent reminds me that it’s time for the midday rice. Have cook send us something.’

After Seimei left, they looked at each other in silence for a moment.

‘You had a close call,’ Kobe finally said.

‘Yes. I’m not sure Demon and I would have survived, if Genba and your men had not come when they did. The water was nearly to my head.’

Kobe raised an eyebrow. ‘Demon?’

Akitada chuckled. ‘There was a rat in the pit. He perched on my shoulder when the water rose.’

‘Dear heaven.’

‘He gave me courage. Did you find the youngster I was chasing?’

Kobe shook his head. ‘I’ve put more men on it. They’re systematically combing that part of the city. Tora says he’s one of the arsonists.’

‘Perhaps, but he was not with the others when they tortured that poor little thief.’

Kobe grimaced. ‘Jirokichi. They call him the Rat. You have a fondness for rats, it seems. He has a reputation, that one. It’s surprising that he was tortured by a gang. Thieves generally protect each other.’

‘Tora says Jirokichi works alone, and those juveniles were bent on revenge for an earlier incident. What is strange is that one gang apparently turned on the other to set him free. I think it means those boys work outside the organization. You found the evidence of arson in the warehouse?’

Kobe nodded. ‘So far, the older men and the girl haven’t talked, but I’ve postponed serious questioning until I can be there. We’re still rounding up all the street boys in the area.’

‘It struck me as significant that the gang freed Jirokichi and then let the young devils run. Perhaps one of the gang has a relative among the arsonists.’

‘Perhaps. But the protection racket run by the organization has been threatened by the fires. Merchants stop paying if their shops burn anyway.’

They sat in silence, pondering this, until Seimei and Tamako’s maid brought in trays of food. There was rice, a vegetable dish, fried bean curd, and pickled melon.

Akitada was hungry and ate with relish, but Kobe only picked at his food. He said suddenly, ‘Do you think the fires have a political purpose, that they are directed at Michinaga and his sons?’

‘Yes. But it’s hardly something I can meddle in.’

Kobe sighed. ‘I have to meddle in it, and I’m no more fit to face the consequences than you.’

‘I know. But you must inform Chancellor Yorimichi, at any rate. Can you talk about your investigation of the Kiyowara murder?’

‘Yes.’ Kobe speared some melon with a chopstick and chewed. ‘As I said, the suspicion falls on the son. He was overheard quarreling with his father. When we asked him about that, he was evasive and looked frightened. So far his mother has protected him, and word has come down from the chancellor’s office to handle the family gently.’ Kobe grunted his disgust.

‘What about the weapon?’

‘No sign of it, but we could not very well search the mother’s pavilion. Whatever it was, it crushed the skull in several places. Most of the damage was to the front of the head. You would think Kiyowara would have defended himself against the attack, but perhaps the first blow was unexpected and struck with great strength. A man, even a young man, could deliver such blows in anger. And he kept striking after his father was down.’

Akitada tried to imagine Katsumi in a violent rage and failed.

Kobe asked, ‘What will you do about the case?’

‘I cannot return to the residence, but mean to talk to the major-domo again. He lives outside. I’ll let you know if there is any new information.’

Kobe pushed his bowl aside. It was still half full. ‘Well, I’d better go and arrest the son.’

Akitada said quickly, ‘Don’t! There might be another explanation. Let me ask a few more questions.’

‘Very well, but it cannot wait much longer. I’ll be following up the business of the arsonists until I hear from you.’

Akitada reached across his desk and opened a small box, taking from it Tora’s amulet. ‘Tora found this in the street after he collided with one of the young rascals. I believe it may belong to the youth Tojiro.’ He waited until Kobe had opened the pouch and looked at the amulet inside. ‘I want to know more about that boy who looks like Katsumi. This is a religious object. I’ll start with Abbot Shokan, I think. He has lost an acolyte and has been suppressing information.’

Kobe reinserted the amulet and handed it back to Akitada. He frowned. ‘Do you think this Tojiro is related to the Kiyowaras or that he is the abbot’s missing lover? You can’t have it both ways.’

Yes, that was the problem. Back in the pit, with Demon perching on his shoulder, it had seemed entirely feasible. Akitada said evasively, ‘I wish I knew. Perhaps it’s a family keepsake. And Tojiro keeps appearing in both cases.’

Kobe gestured towards the amulet. ‘You have only that amulet and a vague resemblance to young Kiyowara. It seems farfetched.’

‘Yes. I had not meant to tell you this much.’

Kobe chuckled and got up. ‘Well, let me know what happens. It’s time I went to see what our prisoners have to say for themselves.’

THE SANDALWOOD TREE

It rained off and on throughout the day, but Akitada enjoyed the excursion. He was finally back on his own horse. The animal was his single weakness for luxury, and he had steadfastly turned down astonishing offers for it from wealthy and powerful men.

Besides, the rain had cleansed the air over the capital, which had been heavy with the stench of smoke and wet rubble for weeks. In the country, the farmers tended their fields, opening sluices to control the abundance of water that had gathered in ditches and holding ponds. The crops looked green and healthy.

Later, in the forest, dripping branches released their moisture in a sibilant cadence, and small birds groomed themselves among the wet branches.

Abbot Shokan received Akitada eagerly. ‘You’ve found him,’ he cried. ‘I knew it. If anyone could, it would be you. Come, come. Sit and tell me. Did you bring him back with you? But no, they would have told me. When will he return?’

Akitada sat, waiting out the effusion. Perhaps his lighter mood had shown in his face. He rearranged his expression. ‘I am very sorry to disappoint Your Reverence, but if I have found your acolyte, I have misplaced him again.’

Shokan’s face fell. ‘What can you mean?’

‘I believe I found him briefly, but he escaped. At the moment, the police are looking for him. He seems to be involved in setting all those fires that have plagued the city for so long.’

Shokan’s lower lip trembled. ‘That cannot be,’ he muttered. ‘He would never… It would be a betrayal of all his principles…’ His voice trailed off, and he shot Akitada a frightened glance.

‘I think Your Reverence knows that the crown prince has enemies at court and in the nation.’

Shokan tried to look blank. ‘What? I cannot imagine what you mean. You must do what you can to rescue the boy if he is arrested.’

‘I am afraid I cannot do that, Reverence. But Superintendent Kobe is a fair man. He will not hold him, if the youngster is innocent.’

Shokan sat for several long moments, staring at Akitada. ‘Then he’s lost,’ he said heavily after a while and bowed his head. ‘He showed such promise. They say the sandalwood tree is fragrant in its first leaves. That is the way he came to me, a young sandalwood tree. Oh, the corruption of this world must be terrible if it swallows up even the innocent children.’

Akitada was uncomfortable in the presence of such grief coming from an old, fat man who had led a life of ease. He thought it hypocritical, though clearly the emotion was real. Perhaps this was what happened to those living ‘above the clouds’. They no longer had any connection with the poor, the laborers, the market women, the prostitutes, and all the innumerable peddlers, traders, and entertainers that scratched out a living from each other and from those just slightly better off than they.

It was even doubtful that this imperial prince-turned-cleric knew anything of Akitada’s world.

His voice harsher, he said, ‘Surely a man of Your Reverence’s status in the political and spiritual spheres can intercede and change even a condemned man’s fate. In fact, you never needed me for that.’ He reached in his sleeve and brought out the amulet. Placing it before the abbot, he asked, ‘Have you ever seen this?’

The abbot snatched up the little pouch and removed the amulet with shaking fingers. ‘Yes,’ he said. ‘Yes. It’s Kansei’s. I gave it to him.’

‘My retainer tangled with one of the arsonists as they were running from the fire. He dropped it.’

The abbot clutched the amulet to his chest. ‘The man could have stolen it.’

Akitada lost his patience. ‘The boy is now known as Tojiro. I think it is time, Reverence, that you told me the truth about his background.’

Abbot Shokan seemed to shrink into himself. ‘I have not lied to you,’ he said softly. ‘I wanted only the best for a child given into my care. And you are wrong about what I can do for him. My hands are tied by my vows. I cannot interfere in legal matters.’

Akitada did not believe this for a moment, but he softened his tone. ‘Without knowing his story, I cannot go to Superintendent Kobe to speak on his behalf.’

Shokan gave him a hopeless look. ‘Then he has already been arrested.’ For a moment it looked as if he would cry like a child.

Akitada did not set him straight.

Shokan said dully, ‘A woman who claimed to be his mother brought him here. That is the truth. He was five and already beautiful. She – her name was Ako – wanted him to receive an education and offered to pay a small sum every year for his upkeep. She did not keep her word, but in time I saw his lively intelligence and began to take a personal interest in him. He seemed to like his life here, and when he was twelve, we decided that he should become an acolyte. His mother agreed readily.’ Shokan made a face. ‘A greedy woman. She wanted money. That such a child should have been born to her!’ Shokan sighed heavily and wiped his eyes. ‘I paid what she asked. He grew more beautiful every year, but he took little interest in the austerities of our lives, and he ran off all too often. He said he went to see his mother. If so, she had a bad influence on him. I decided to postpone his tonsure.’

And that, of course, explained why the young acolyte looked no different from any other boy. Akitada was not sure if he liked the abbot’s story. It might be true that Shokan, being cut off from the world, had taken a fatherly interest in a poor child and furthered his education, and that the boy had been tempted by the livelier world outside the monastery. It was equally possible that the boy had been forced into a sexual relationship he had no taste for and had run away. But he could not ask these questions and therefore focused on something else. ‘Are you certain that the woman was really his mother?’

Shokan said quickly, ‘No. I wondered many times, but the boy claimed she was.’

‘And you really have no idea where I might find her?’

‘None. I never saw her again after I paid her, and the monk I sent to look for her said she had disappeared. I confess I did not look very hard for her.’

‘Are you aware of any connection between the boy or his mother with the Kiyowara family?’

‘Kiyowara? No.’

Akitada, doubting Shokan’s memory, said, ‘Kiyowara was the Junior Controller of the Right. He was murdered a few days ago.’

Shokan blinked. ‘Really? I take little interest in worldly matters. Kiyowara? He must be one of the new men. There is too much violence. We live in the latter days of our faith. What makes you think Kansei had any connection with the man?’

‘He bears a rather striking resemblance to the young Kiyowara heir. Could he be the murdered man’s son?’

Shokan looked astonished and then a little excited. ‘I have no reason to think so, but I always felt that he was an unusual child. It surely would make this an extraordinary story.’

Stranger things had happened, Akitada thought, but he decided that he must ask another man about this. He took back the amulet, promised to keep Shokan informed about the boy’s fate, and left.

As he walked back to get his horse, it occurred to him that he might as well talk to the monk who had come to his house. He had surprised him with his disapproval of the acolyte and the abbot’s concern. He looked around and saw a group of small boys sitting under a pine tree. They were peering at a small bamboo cage.

Akitada joined them and admired the large, fierce-looking cricket inside. With the ease of upper-class children, they instantly included him in their discussion.

‘Maro caught him. We’re going to catch another and make them fight,’ said one.

‘He’ll be a vicious fighter,’ said another.

Their ages ranged between five and nine years. Maro was an older boy, but it was the youngest who was most impressed with the insect’s viciousness. The child was very much as Yori had been before his death. The pain of that memory was still sharp, but Akitada reminded himself of the little girl at home. Would she catch crickets some day? Perhaps not. Girls were more likely to collect fireflies. After an exchange of a few observations on crickets and other small creatures, he asked, ‘Would one of you know where I might find Saishin?’

They looked at each other and made faces. Maro got up reluctantly. ‘I’ll take you, sir,’ he offered.

‘Thank you. That’s very good of you,’ Akitada told him. They started across the monastery compound. ‘Do you by any chance remember the boy Kansei?’

Maro nodded. ‘He was one of the big boys. He was very disobedient,’ he said, ‘but His Reverence liked him, so he got away with it.’ He sounded matter-of-fact and a little envious.

‘Ah. What sorts of things did he do?’

‘Well, he ran away a lot. And then the monks would have to go search for him and that made them cross.’ Maro grinned. ‘And he didn’t do his sutra readings. And he’d go into the woods with a bow and arrow and shoot birds and things. The monks said he’d come to no good.’

‘And Saishin? He didn’t like Kansei much either, did he?’

‘Oh, Saishin hated him. We think it’s because His Reverence liked Kansei the most, even though Saishin is the best monk we have.’

‘The best? Really?’

The boy nodded. ‘Oh, yes. He performs more austerities than anyone, and he’s forever praying. See? There he is now.’ Maro stopped and pointed at the dark figure of a monk seated outside one of the temple halls. Saishin was in meditation pose, his hands on his knees, his eyes closed.

Maro said in a whisper, ‘I’ll leave you then, sir,’ bowed, and ran off at top speed.

Akitada decided that the boys had liked Kansei. There had been that small note of admiration in Maro’s tone when he had mentioned Kansei’s disobedience. They did not like Saishin.

Akitada approached the seated monk. The sound of his steps crunching the gravel did nothing to interrupt his meditation. Akitada was forced to clear his throat.

The hooded eyes opened slowly and looked at him. Saishin’s expression did not change.

‘You may recall coming to my house not long ago,’ Akitada said.

After a disconcertingly long moment, Saishin nodded. ‘I remember.’

‘It occurred to me that you might have some information that would help us find the lost boy.’

‘It is not likely.’

‘Was it you who saw Kansei with some other youths in the market?’

‘Yes.’

Akitada snapped, ‘Look, His Reverence wants the boy found. The least you can do is make an effort. Do you want me to go back and tell him you refused to answer my questions?’

Saishin did not react to this threat. He said in the same flat tone, ‘That would be a lie.’

‘You don’t want him found and returned to the monastery. Am I right?’

This time the pause was even longer. Saishin blinked and said, ‘It would be better for the monastery if he did not return.’

‘Why?’

‘He doesn’t belong.’

‘That’s nonsense. He’s been living here since he was five years old.’

‘He doesn’t belong.’

‘You mean he wouldn’t make a good monk?’

‘That, too.’

Akitada bit his lip. ‘Can you at least describe the boys you saw with him?’

Saishin frowned. ‘Scum. Criminals. Sometimes there were only two, sometimes five or six. They were his age, but bad. They had knives and the scars from knife fights. Devil’s spawn, all of them.’

‘No doubt,’ Akitada said dryly. ‘Do I take it that you kept a regular watch on the market area in order to keep the abbot informed about Kansei’s company?’

Saishin flushed. ‘I may have combined other errands with keeping an eye on one of our acolytes.’

And that meant that Saishin had done his best to blacken the boy’s reputation with the abbot. It might be immaterial, but Akitada kept it in mind.

‘What about the boy’s mother. Do you know where she lives?’

‘No. His Reverence asked me to find her, but she had moved away.’

Akitada gave up and got his horse.

At home, Trouble greeted him with the usual exuberance, but Genba and Seimei had their heads together studying a piece of paper.

Akitada dismounted and waited for Genba to take his horse to the stable. ‘Where’s Tora?’ he asked, looking around.

‘Tora got tired of sitting around so he offered to go to run an errand for cook,’ Genba said. ‘He’ll be back soon.’

Seimei still stood with the piece of paper in his hand. ‘What is it?’ Akitada asked. ‘Did someone bring a message?’

Seimei came and said, ‘After a fashion, sir.’ He held out the scrap of paper. It was dirty and crumpled, and Akitada hesitated to take it. ‘It was wrapped about a large stone and thrown over the back wall,’ Seimei explained.

Akitada took it and smoothed it out. The writing was in a good hand. It said, ‘Beware of fire.’