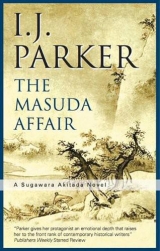

Текст книги "The Masuda Affair "

Автор книги: Ingrid J. Parker

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

She raised her hand to touch his cheek. ‘Oh, Akitada,’ she murmured, ‘please forgive me for what I said. And for what I thought.’

He put his hand over hers. The tears in her eyes brimmed over, and he took her in his arms. They stood, clinging together, under the empty swallow’s nest.

After a long moment, he said, ‘There’s nothing to forgive. This has been very hard for you, too.’

She clutched at him. ‘I said those terrible things because I wanted to hurt you. I thought you did not love us anymore.’

At the time he had in fact turned away from her and given his heart to another woman, a woman of whom he still sometimes thought with a desire that heated his body. He did not know any longer what he felt for Tamako. Struggling with his cursed honesty, he let pity overcome the urge to stop a scene that was rapidly disintegrating into something he was not ready for. He said nothing, but held her a little closer and stroked her hair.

After a moment, she disengaged herself with an embarrassed laugh and brushed the tears from her face. ‘Your arm? Has it been seen to?’

‘Yes. Seimei put some salve on it.’

‘Please come inside and tell me what happened in Otsu.’

They sat across from each other near the fallen blind, and he told her. He added, ‘Genba asked what happened, but I was too tired to deal with his questions or to discuss Tora’s absence, which seemed to trouble him more.’

‘Genba is worried about Tora?’

Akitada was a little hurt that she should be distracted so easily from his problem to Tora’s. Her lashes were still wet from tears and her nose was pink. For a moment, she reminded him of the boy. A ridiculous notion. He pulled himself together and said, ‘Tora seems to have left my employ.’

‘What?’ This time the shock in her voice and face was palpable. ‘Akitada, what happened? Something must be dreadfully wrong for Tora to leave you.’

He snapped, ‘Nothing out of the ordinary. Tora is once again besotted with some whore from the quarter. He has no control over his sexual urges the moment a loose woman makes eyes at him.’

She flinched at his language. ‘Tora has a kind heart,’ she said. ‘He does not make distinctions.’

He snorted.

‘Please don’t be this way, Akitada. I think you must have misunderstood something. This isn’t like Tora.’ When he shook his head stubbornly, her eyes flashed and she cried, ‘Oh, Akitada, think! Whatever Tora has done, don’t forget what you owe him. He saved your life. He came for you in Sado. He fought beside you. You must find him and bring him back. Neither of you will ever be happy again unless you do.’

He was surprised at her urgency and digested this in silence. She was right, of course, and that rankled. He had thought himself the injured party and was still not altogether convinced that he wasn’t. ‘What do you suggest I do?’ he grumbled. ‘Do you want me to question every madam, porter, and whore in the quarter until I find him? And then apologize because I have found his work unsatisfactory lately?’ He turned and pointed an accusing finger at the ragged hole in the veranda floor. ‘This would never have happened, nor this –’ he gestured towards the stained ceiling – ‘nor all the other leaks in our roofs, nor the crumbling outer wall, nor the gods know what else, if Tora had done even a part of the chores he owed me.’

She closed her eyes briefly before his anger, then said, ‘You’re right, but you must find him all the same. There are more important things owed between you. Do you really want to lose Tora, too?’

He brushed a weary hand across his face. ‘What does it matter? What does anything matter?’

‘Oh, Akitada.’ Tamako jumped up and stamped her foot. ‘It matters to me. It matters to Tora. It matters to all of us who care about you.’

His resistance crumbled. He looked up at her uncertainly. ‘You really think I should look for Tora?’

‘Of course.’

‘But what about the boy?’

‘You said he was safe. Find Tora first. The rest will fall into place.’

‘Well …’

‘Please.’

Akitada saw the entreaty in her eyes and sighed. ‘Very well. But if he doesn’t have a very good explanation for this latest stunt, I’ll be done with him.’

‘Thank you.’ She smiled.

His heart lifted a little. Whatever Tora was up to, the search would take his mind off his other troubles. He rose and glanced towards the veranda. ‘Stay off those boards until they are mended. If you and Seimei will make a list of repairs and leave it on my desk, I will see what can be done. I’ll try to be back for the evening rice.’

Lord Sadanori

The sun was up when Tora got back to the capital. He was limping badly and put one foot in front of the other by sheer willpower. There was a hole in one of his boots, and the sharp gravel of the highway had cut his foot. He was no longer hungry, though he had eaten nothing since the previous morning, but the lack of food and sleep made him light-headed.

Perhaps he had made this dreadful trip for nothing. Perhaps Hanae would receive him with a hug and a smile. She would make him sit down on the front steps beside the morning glory vine and take off his boots. Then she would bathe his sore feet and bandage them, feed him some warm rice gruel, and hold him in her arms.

But Hanae was not home. Only the white cat greeted him, mewing plaintively and rubbing against his legs. The cat was Hanae’s, just as Trouble was his. Ordinarily, the cat did not care much for Tora, whom it seemed to consider an interloper. Trouble did not discriminate. He loved both his owners equally. But now the cat, an opportunistic creature, was distraught and, thinking it had been abandoned by its mistress, it greeted Tora effusively.

Followed by the mewing cat, Tora limped to the backyard. He drank at the well and washed his face and hands. Then he filled the dog’s dry water bowl. The cat drank daintily, twitching its tail. It preferred fish broth.

‘Make yourself useful,’ growled Tora, taking off his boots to wash his wounded foot. ‘Catch some rats. Your mistress always said you were a good mouser.’ The cat pressed its head into his hand and purred. Tora thought of Hanae and felt pity for the animal. ‘I’m hungry myself,’ he said apologetically.

The boots were in bad shape, but he had no others. Barefoot, he limped back to the veranda, found the key where they hid it under a rock behind the vine, and unlocked the door. The stale air and silence of emptiness greeted him and made his heart heavy again. He took off his sword and hung it on its nail. Since he was no longer in the service of a noble family, he could be arrested for wearing a sword in the capital. Plus, if Hanae returned, she would know he had been here. The mewing cat had followed him inside and was investigating both rooms for its mistress. Tora found a worn pair of straw sandals and cut inserts from these for his boots. Then he wrapped his lacerated foot in old rags and slipped the boots back on. In the kitchen, he rummaged about for food, but Hanae had cleaned up and the larder was bare.

‘Come on,’ he told the cat. They went back out and Tora re-locked the house and hid the key again. With a sigh he left, closing the gate carefully behind himself. The cat jumped up and over and mewed loudly. Tora kept walking. When he reached the corner, he glanced back. The cat had followed him halfway along the block and sat in the middle of the road looking after him.

Near the market, he used his last copper to buy a rice cake from a street vendor and ate it on the way. Following the directions from the fat servant in Uji, he reached Sadanori’s residence quickly. He did not expect to find Hanae there, but hoped to learn something about its owner.

The nobleman’s large compound occupied an entire city block and was walled all around. Its main gate on Muromachi Street stood open on a scene of great activity.

A small crowd had gathered on either side of the gate, and Tora joined them. They watched as a train of porters and carts tried to deliver building supplies, while inside grooms and servants clustered around an ornate, painted ox-drawn carriage. An irate little man in the white clothes of an upper servant jumped around in front of the train of porters, waving his arms and shouting for them to stop, to go away, to back up, to go around to the other gate. The men at the head of the train stopped, but the others were pressing forward from behind. In due course, trouble ensued. Two porters were crowded aside by a cart backing up and dropped a load of planks on someone’s foot. Cries and curses followed. A mule shied and galloped into the cluster of servants, shedding roof tiles from the basket strapped on its back. The servants scattered, frightening the ox. The ox made for the stable building with its handler hanging on to the reins and digging in his heels to stop him. Outside the gate, the lumber bearers faced off against the tile carriers because one man had been trampled by a member of another group. Boards and beams lay everywhere, and large baskets spilled clay tiles into the street. The watching crowd cheered.

Tora used the fracas to slip into the courtyard undetected. When the ox had pulled away the carriage, it had revealed a nobleman in a rich red silk robe and black court hat. He wore a sword and held a gilded fan, with which he fanned a round, pale face with a small mustache and chin beard. Beside him stood Ishikawa, a head taller and much slimmer and still in the clothes he had worn in Uji. Both stared at the commotion with identical expressions of shock and disbelief.

Tora ducked behind a pile of stacked firewood, squatted down, and peered around the corner. The man in red must be Sadanori. Ishikawa had ridden back from Uji posthaste to report Tora’s visit. The temptation to confront the great lord and wipe that smug, superior expression off his face was great, but Tora resisted. He wished he knew what they had talked about, but was even more curious about His Lordship’s intentions. Had he just stepped from the elegant carriage, or was he about to leave in it?

Eventually, order was restored, and the ox driver backed the carriage to where it had stood before. The workmen and porters gathered up their mules and scattered goods and left, and Lord Sadanori and Ishikawa walked around the carriage. After some more words with Ishikawa, Sadanori got into it.

There was a chance, a small chance, that the bastard had hidden Hanae elsewhere, but had spent the night in his own residence. And now he was reporting for duty at the palace. Tora knew very well what full court attire looked like.

The carriage turned and headed out the gate, the front runner shouting, ‘Make way,’ the red silk tassels on the black ox bobbing, the green-and-gold carriage swaying between its two huge black-lacquered wheels, and a retinue of servants in white jackets and short, full-legged pants trotting along on both sides.

And then the gate closed after them.

Tora sat behind the wood stack and thought about what he had just witnessed. Hanae was not likely to be in Lord Sadanori’s women’s quarters, playing nursemaid to his children and discussing her future duties with the pregnant wife. There was no pregnant wife, according to Sadanori’s mother. And Ishikawa had dashed back here to report Tora’s visit. All of this suggested that Sadanori had indeed abducted Hanae and that she was hidden elsewhere. Had Sadanori given Ishikawa instructions about her?

Tora peered around the wood pile. Ishikawa was walking towards the inner gateway. Tora could see the tops of trees beyond. From the distance came the sound of hammering. Ishikawa had probably gone to check on the arrival of the pack train at the other gate. Wherever Hanae was, Sadanori must think her well-hidden.

‘Yoi!’ a voice shouted practically into his ear. A bearded man was looking down at him over the top of the wood pile. ‘What do you think you’re doing there, you lazy turd? Sleeping in the middle of the day? Move your sorry arse and go to work.’

Tora shot up. The man was the senior servant who had tried to stop the pack train. ‘Er,’ Tora stammered, trying to think of some explanation for what he was doing there.

‘You thought you could just hide back here and then show up tonight with the rest of them to collect your wages,’ the servant said, waving an accusing finger. He eyed Tora’s blue robe, no longer neat or particularly clean after his excursions, but still better than the average laborer’s shirt and loin cloth, and frowned. ‘Who are you anyway? You with the supervisor’s staff?’

‘Yes,’ Tora lied. The building project, whatever it was, needed professional supervision, and Sadanori’s servants must be used to strangers roaming about. He yawned hugely. ‘Sorry,’ he said with a grin. ‘Been up all night writing changes and checking orders. I was just grabbing a little shut-eye until they get unloaded.’

The servant looked at Tora’s red-rimmed eyes and tired face. Oh. Sorry I woke you, friend. Go back to sleep.’

‘Thanks, but now I’m awake, I’ll stroll over and see what’s happening.’

‘Keep to the far side of the lake. The ladies don’t like strange men walking about near the house.’

Tora gave the man a wave and set off towards the inner gate. He tried not to limp too noticeably. All this talk about sleep had made him realize how tired he was. But now that he was in the badger’s den, he was not about to leave without seeing everything there was to see and perhaps learning a few things in the process.

The smaller gate led on to a wide inner courtyard that stretched between the main house and its two wings all the way to an artificial lake. Tora considered ignoring the servant’s warning, but if he got caught near the women’s quarters, all hell would break loose. So he followed the path around the lake to the sounds of sawing and hammering.

A separate hall was nearing completion. The framework was up, and so was the roof. Beyond the construction site was the east gate, where the pack train had arrived and was unloading supplies. Sadanori did not spare money on his projects. At least twenty carpenters with their assistants were at work on the building. They were raising more columns, sawing boards for floors and verandas, and carving banisters, railings, brackets, and ornaments for the eaves.

Ishikawa stood in front of the building. He was talking to a short, corpulent man in a plain gray silk robe. The man held a roll of papers in one hand and gesticulated with these from the goods to various groups of craftsmen. Tora guessed that he was the building supervisor. It all looked harmless and normal enough.

He crept a little closer. At the gate they were still unloading and stacking boards. The supervisor interrupted his conversation with Ishikawa and turned to one of the carpenters. Ishikawa scanned the area. Tora busied himself picking up remnants of wood and other building debris, hoping Ishikawa would not pay attention to a mere worker.

When he heard a shout, he jumped and risked a glance, but the supervisor’s anger was directed at a carpenter, who rose from his labors and stood, shaking his head. Evidently, he was in trouble. Ishikawa joined them. The supervisor pointed to the gate. The carpenter pleaded. Ishikawa became impatient. He said something to the supervisor, turned, and stalked off in the direction of the main house.

Tora considered following Ishikawa, but the supervisor cut off the carpenter’s pleading and went to talk to another group of workers. The carpenter, an elderly man, gathered his tools and walked out of the east gate, his hanging head and slumping shoulders showing his dejection. Tora followed.

The gate opened on Karasuma Street. The carpenter turned south. Tora caught up with him at Sanjo Avenue. ‘Hey,’ he called out. The carpenter did not turn; he appeared sunk in despair. When Tora touched his shoulder, he stopped and looked up. On closer inspection, the man did not look very promising. Tora took in his emaciated frame, the rheumy eyes, the toothless mouth, and wondered if he had darkened his thin hair to appear younger. He bit his lip, no longer sure what to do.

‘Sorry to rush after you, uncle,’ he said, ‘but I heard what just happened. You got fired, didn’t you?’

The old man nodded. He ran the back of his hand across moist eyes. ‘I’m a good carpenter,’ he said sadly. ‘The best. And I work fast. But my back’s bad, and I can’t lift heavy beams. So I’m no good anymore.’ He looked sorrowfully at his wooden toolbox and sighed. ‘I’ll have to sell my tools for a few coppers.’

‘Don’t do that. I know where there’s some work.’

The carpenter looked up, hope in his eyes. ‘Where?’ he asked. ‘I’ll do anything. May the Buddha reward you! We’ve almost no food left at home.’

‘I’ll tell you, if you’ll tell me about Sadanori and Ishikawa.’

The old man blinked. ‘The great live above the clouds. I’m only a simple man.’

Tora had never been troubled by his own lowly status and had little respect for men who behaved like Sadanori – or Ishikawa. ‘If you keep your eyes and ears open, you learn things,’ he pointed out. ‘What did Ishikawa and your supervisor talk about before you got fired?’

‘The hall. Mr Ishikawa complained about the money and how long it was taking. As if the great lord didn’t have all the money in the world!’

‘What’s the hall for?’

‘They say it was meant for a favorite, but was never finished. Now he wants to live in it himself. Calls it the Lake Hermitage.’

Nothing in that. Nobles were always pretending that the world wearied them and they only wanted a simple life. ‘Did Ishikawa say where he was off to in such a hurry?’

‘He’s riding to Otsu.’

‘Otsu? Why?’

The carpenter did not know. Tora decided that Ishikawa had gone to visit his mother. ‘You hear any talk about Sadanori’s affairs?’ The carpenter looked blank. ‘I mean with women. Courtesans, entertainers?’

The old man grinned. ‘The great lord spends time in the pleasure quarter. Is that what you mean?’

It was hot, and the sun was already high. Tora felt lightheaded with exhaustion and lack of food. He was frustrated that he was not getting anywhere, but some remnant of pity for the old man kept him from shouting at him. ‘You were there yesterday. Did you see a sedan chair delivering a young woman? About the middle of the morning?’

‘No. I think the ladies come and go by the north gate.’

So much for that. Tora did not really believe that Sadanori would bring Hanae to his home, anyway. ‘What about Ishikawa?’

‘Ishikawa’s the betto. He runs everything. Him and the lord are like this.’ The carpenter put two fingers together. ‘He’s the lord’s eyes and ears.’

Tora sighed. ‘All right. Go to Oimikado Avenue and ask for the Sugawara residence. When a big man opens the gate, tell him Tora sent you to do some work on the house.’

The carpenter bowed deeply. ‘You are a saint,’ he said. ‘I bless you. My wife blesses you. My sons, who are soldiers, bless you also, wherever they are. And so do my grandchildren and their mothers.’ He grasped Tora’s hand and kissed it.

Tora snatched his hand back. ‘Go on,’ he growled. ‘And make sure you do good work for them. They’re my people.’

He crossed Sanjo Avenue before the old man could embarrass him further. While the relationship between Ishikawa and Sadanori was something to keep in the back of his mind – Tora believed the worst of both of them – he still did not know how to find Hanae.

Worse. He was at the end of his tether. He had no patience left. Only sheer dull willpower kept his legs moving. The linings in his torn boots had shifted, and his bare soles were again scuffing the dirt in the road. Tora sat down on the other side of Sanjo, took off both boots, and examined them and his feet. One foot was bleeding through a crust of dirt and gravel; the other had developed a large blister. He had lost the straw inserts. No matter. He must go on. Rewrapping his feet, he put the torn boots back on and limped towards the pleasure quarter.

He should have gone directly to Hanae’s dancing teacher, but Master Ohiya was one person Tora preferred to avoid. They were acquainted, but not on friendly terms, and for very similar reasons. Each despised the other, regarding him as Hanae’s certain doom, as a seducer and destroyer of something precious. Tora thought Ohiya no better than a pimp who trained innocent young girls to become prostitutes. While he had nothing against prostitution in general, he was not so tolerant about his wife’s activities. Ohiya, on the other hand, knew that he had discovered and perfected a fine talent with prospects of a great public career until a low-class yokel had ruined her. Their contest over Hanae had ended with Tora’s victory and Ohiya’s bitter enmity.

Tora trudged through the quarter, from wine house to wine house, asking for Hanae or one of her friends. Nobody had seen his wife recently. He had expected that. But finding and speaking to the girls who might know something because she had worked with them brought him more trouble than he had bargained for.

It was afternoon, and the women were either still asleep or dressing for their nightly engagements. Tora was exhausted, dizzy from heat and hunger, and in pain. His appearance was no longer reassuring. His clothes looked dirty and wrinkled, his boots gaped, revealing dirty toes, he was unshaven, and his hair had come loose. Besides, he had developed a manner of glowering at people from bloodshot eyes. He was not welcome. Doors were slammed in his face. No longer able to draw on his stock of charm and flattery, he resorted to demands and threats. One woman cursed him and emptied a bucket of night soil on him when he turned away. Most of it missed, but enough soaked the back of his blue robe to add a fetid stench to his other unlovely attributes.

When he finally found a girl who knew Hanae, she looked at him askance and suggested that Hanae must have come to her senses and left him. To emphasize the point, she told him that Sadanori had shown a great interest in Hanae. And she said that he should ask Rikiju if he didn’t believe her.

Rikiju took pity on him. Tora found her in a rented room in the back of a disreputable restaurant. She was in her thirties, an example of what happened to women in the pleasure quarter if they did not find a lifelong patron before their youth faded. Her old robe hung open, revealing too much of a bony figure. From a hook hung her only good gown: the silk stained and torn, and the embroidered flowers faded. She wore no make-up, and her face was both haggard and puffy from late nights and too much cheap wine. But she commiserated with him and offered to share the modest meal she was eating.

‘You look terrible,’ she said. ‘Eat just a little.’

Tora thought the same of her and shook his head. He told her what had happened.

‘Well,’ she said dubiously, sucking the last bits of food from her bowl, and then wiping it with one of her fingers, ‘if it’s Sadanori who got her, she won’t be getting back today.’ She licked her finger and wiped it on the sleeve of her robe. ‘He goes to that much trouble only when he’s serious.’

‘He’s done it before?’

‘So they say.’

‘I know he took her, and I’m going to get her back if I have to fight him and a thousand armed guards.’ Tora trembled with rage at the thought of Sadanori raping his Hanae.

She eyed him with concern and shook her head. ‘You won’t find her. He’s probably taken her to a private house. He’s done it before. The best thing is to wait for her to come back. He gets tired after a while. They say he’s one of those men who want what they can’t have. It’s not getting a woman that heats his blood. Until she’s his, his fire burns hot; then he’ll lose interest quickly and send her home. Smart thing to do for Hanae is to let him have his way.’

‘Bite your tongue.’ Tora glared at her. ‘My Hanae will fight the bastard to the death.’

Rikiju looked away. ‘Hanae’s a sensible girl. She’ll be all right. Now I’ve got to get ready for work.’

‘What do you mean, she’s sensible?’

She sighed and got up. ‘Nothing. Don’t worry. Go home, Tora.’

After that, Tora was no longer quite rational. Back on the street, he pushed people out of his way and snarled when he asked for information. Most of those he accosted fled or slammed their doors. He had only one name left before he had to crawl to Master Ohiya.

The dancer Kohata was Hanae’s rival. The two women often appeared at the same parties and they competed for work. Tora tracked Kohata to the best restaurant in the quarter. To get this information, he threatened an old woman who had been hobbling out of Kohata’s home with bodily harm. She told him that the entertainer had left the previous evening for a party with important clients and had not returned yet.

At the entrance of the Fragrant Plum Blossom, Tora cornered a maid and demanded to speak to Kohata. The maid ran from him, and the restaurant’s owner arrived and threatened to call the constables. Tora pushed the man aside and went in. A young boy with the knowing face of an incipient pimp was sweeping the floor of the corridor. Otherwise the place seemed to be empty. The owner made the mistake of grabbing Tora’s arm. Tora whipped around, grasped the man’s jacket with both hands and slammed him against the nearest wall, which, being paper-thin, collapsed. Then he turned on the boy.

‘Where’s Kohata?’

The boy backed away. ‘She … she’s in the “Willow Pavilion”.’

Tora grabbed his shirt and twisted. ‘Where, you brainless oaf?’

The boy gasped, ‘In the back. Through the garden.’

Tora pushed him aside and stormed out of the restaurant’s back door and into the garden. Behind him, the owner and the boy were shouting at each other.

Tora ran to the small building under the willow tree and burst through its door without knocking. The room was empty except for a pile of silk robes and two naked lovers in an interesting configuration of entangled limbs. Under normal circumstances, Tora would have taken notice of their inventiveness, but in his mind’s eye he saw Sadanori embracing Hanae, and he went to seize the woman by the arm and pull her away from the man.

Kohata was furious. She shouted at Tora. Her frightened client, a fat old man, grabbed frantically for his clothing and stumbled into it.

Tora attempted to calm her down enough to ask her about Hanae, but his time had run out. Footsteps and shouts sounded outside. When he turned, he saw red-coated constables armed with chains and wooden clubs. Behind them came the restaurant’s owner, the boy, the maid, and assorted strangers.

Tora abandoned Kohata and dashed out through the back, vaulting over a balustrade and then scrambling over a fence. Outside, he ran for blocks until the sole of one of his boots came loose, caught, and tripped him. He fell headlong and hard, scraping his left cheek and both elbows on the gravel.

The pain cleared his head a little. He sat up, took off the ruined boot, and tossed it away. Then he got to his feet and limped to Master Ohiya’s house.

Ohiya’s young male servant answered, then tried to slam the door when he saw a disheveled, bleeding man outside. Tora snarled, ‘Out of my way,’ and pushed him aside. He found Ohiya by following drumbeats to a large room at the back of his house. Ohiya himself was beating the drum, seated cross-legged on the wooden floor while a young girl went through a dance routine and three others awaited their turn.

The girls were very young, under fifteen, and they squealed when Tora burst through the doorway.

Ohiya looked up, cried, ‘Oh!’ and stopped drumming. In a shaking voice, he asked, ‘What do you want?’

Tora cast a glance at the frightened girls huddling in a corner and said, ‘Sorry. I need a word.’

Ohiya’s eyes blinked, then narrowed in recognition. ‘Tora? What is this? How dare you burst in here like this!’

‘Hanae’s gone. Stolen. I know who has her, but I don’t know where she is. You’ve got to help me, Ohiya.’

Ohiya got to his feet. He was a slender man in his forties who whitened his face and touched his lips with red safflower juice. Today he wore his working clothes: a black silk robe under an embroidered jacket. The jacket was sufficiently feminine that, in spite of his tall figure and the male hairstyle, it and the make-up made his gender vaguely dubious. This was one of the reasons Tora despised him.

Now Ohiya curled his lip and said, ‘You look disgusting. What dog has dragged you out of the gutter?’

Tora bared his teeth and advanced on him. The girls squealed again and put their arms around each other. ‘Don’t play with me, Ohiya. Either you help me find her or I’ll know you had a hand in this.’

Ohiya skipped a few steps away. ‘Don’t you dare touch me, you brute.’

Tora backed the dance master against the wall. Leaning forward until they were practically nose to nose, he snarled, ‘Tell me where Sadanori’s hidden her or I’ll make sure that you never dance again.’

‘I know nothing,’ Ohiya squealed. ‘Don’t touch me, you monster!’

Tora held a fist under his nose, and Ohiya screamed for help. Outside, other shouts answered. A moment later the room was full of burly men, some of them constables. Next, Tora was clubbed over the head and thrown on the floor, with two hefty men sitting on him and an excited babble of voices dinning into his ears. Waves of pain, fragments of Ohiya’s complaints, prattle from the four little maidens, questions by constables, and excited chatter from neighbors and bystanders washed over him like a deluge – along with the knowledge that he had bungled the most important job of his life. He closed his eyes.

![Книга [The Girl From UNCLE 01] - The Global Globules Affair автора Simon Latter](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-the-girl-from-uncle-01-the-global-globules-affair-170637.jpg)