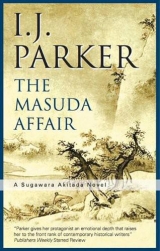

Текст книги "The Masuda Affair "

Автор книги: Ingrid J. Parker

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

SEVENTEEN

Birds and Rhubarb

After his second visit to the Masudas, Akitada debated talking to the warden again, but it was getting late. He had not eaten since that morning, and by the time he did, it would be dark. Besides, there was the problem of where he was to sleep. He rebelled against returning for a third time to the inn where he had been publicly humiliated, and where the fat innkeeper might well balk at admitting such a guest, even without a small boy victim in tow.

He settled the problem of food by stopping in the main restaurant in Otsu. It was busy, and he felt reasonably anonymous. He enjoyed the steamed dumplings with shrimp and yams, and then found a quiet backstreet lodging house.

Feeling pleasantly tired, he opened the doors to the garden to let in the cool breeze, and then lay down where he could look up at the starry sky.

He had much to mull over. Foremost, of course, was the servant’s shocking charge that Peony had poisoned young Masuda. The second lady, while not precisely charging Peony with murder, had hinted at the same thing. But improperly prepared warabi was an uncertain method of killing a healthy yoting male, no matter how much of it he ate.

Still, the idea of poison was troublesome. The Masuda ladies both had motives. They were the scorned wives. And Akitada had not liked the way Lady Kohime had glanced at the old lord’s dish while she had chattered about poisons. Everything about her suggested that she had been raised in the country, where they had a good knowledge of herbs and plants. The old man stood between her and her daughters and a very large fortune.

Still, if young Masuda had been poisoned, Dr Inabe would have known. He would certainly have reported a murder. Or would he? His friendship with the Masudas might have kept him silent.

The doctor’s room had contained shelves of stacked papers and books. Chances were the man had kept records of young Masuda’s illness. Perhaps he had even left notes about his postmortem findings on Peony. Akitada also wondered where the boy fitted into the tangled relationships and motives, but the child was no longer his only reason for searching for answers.

The stars were extraordinarily clear, as was the great river created by the God of the Sky to separate his daughter from her lover. What importance the Tanabata legend attached to bringing people together! He was suddenly overwhelmed by loneliness.

The stars blurred as his eyes moistened with self-pity. Ashamed, he fought the emotion. It was a long time before the hurt faded and he slept.

Akitada decided to share some of the information with the warden, but when he mentioned the servant’s story that young Masuda had been poisoned by Peony, Takechi became agitated.

‘Not a word of truth to it,’ he cried, waving his hands. ‘It’s their grief talking. That death hit them hard and so they have to blame it on someone. His Lordship went mad, and the old man is simple-minded and loyal to his master. If the old lord had not lost his mind, he’d have seen the truth in time and that tale would never have started.’

Akitada raised his brows. ‘So there’s gossip about it. I understood the servant and the second lady to say that young Masuda became ill at Peony’s house and that Dr Inabe was consulted?’

‘Young Masuda had the flux. A common enough ailment around here. People will drink or eat the wrong things.’

‘Like warabi shoots?’

‘Warabi? The warden looked blank. ‘If it was, nobody mentioned it to me. Anyway, it wasn’t a police matter.’ They looked at each other, and the warden became anxious. ‘You don’t think this is connected to the doctor’s murder, do you?’

‘I don’t know. When you have an unexplained murder, you tend to wonder about everything. I’d like your permission to return to the doctor’s house to go through his papers in case they contain a clue to his death and young Masuda’s.’

‘Of course. Shall I send a constable along to give you a hand?’

‘Thank you, no. I think you need your men. Do you want me to reseal the place when I finish?’

‘No need for a seal. The servant’s watching.’

Akitada started to point out the need for keeping the scene of a crime secured until an investigation was complete, but thought better of it. He asked instead, ‘Who inherits the property?’

‘A nephew. We’re trying to contact him.’

‘Then he does not live here?’

‘He’s not been around for years. The servant says the young man travels a lot.’

‘Hmm.’

The warden chuckled. ‘If you’re thinking he might’ve returned to kill his uncle for the house, I doubt it. It’s practically a ruin, and there was no money apart from the little bit of silver in the trunk.’

This saintly reputation was beginning to irritate Akitada. ‘Did the neighbors see anyone?

‘Just the usual. Servants leaving and returning from shopping. A mendicant monk. A post boy with a letter for someone. A sedan chair that picked up one of the ladies for a visit to her shrine and brought her back again.’ He shuffled among his papers. And, yes, the fishmonger with a basket of fish for one of the houses.’

‘You checked them all?’

‘Yes.’ Gloom settled over the warden again. ‘I hope you turn up something.’

Warden Takechi had not bothered to leave a constable at the gate, and so Akitada wandered in uninvited. The doctor’s old servant was sweeping the courtyard.

He blinked, trying to recall Akitada’s name.

‘I’m Sugawara. The warden and I came yesterday. I have permission to look through your master’s papers.’

The servant nodded and put his broom aside. ‘The ladies asked about the funeral,’ he muttered as they walked through the tangled garden. ‘Couldn’t say. The body’s gone. Not even monks chanting. Disrespectful.’

‘The arrangements should be made by Dr Inabe’s relatives. He has a nephew, I hear.’

‘That one.’ The old man spat.

‘Wait until you hear from Warden Takechi.’ Akitada glanced around the lush wilderness. The garden was filled with sound. Birds were singing and chirping, calling out to each other and answering, challenging rivals or warning of the human presence among them. ‘The birds are doing their best to make up for the lack of chanting,’ he said with a smile.

The servant nodded. ‘They know,’ he said quite seriously. ‘Waiting to be fed. I’ll get some food.’

Akitada looked up into the dense branches. The foliage was alive. Did they know their benefactor was dead? They must have seen Inabe’s killer come with murder on his mind and watched him leave, his hands stained with the blood of their friend and that of one of their own. It was a foolish speculation, and Akitada turned to business.

The warden’s people had left the door to the studio unsealed. Muttering angrily under his breath, Akitada walked in. If anything, the stench was worse today. Like the warden, Akitada went to raise the shutters to the back garden. Light, fresh air, and birdsong poured in.

The room looked the same, except that the body was gone. The doctor’s blood still stained the floor, though, and attracted an occasional fly. More flies crawled on the dead crow. The warden had also taken the murder weapon, but the broken birdcage still lay there, and Akitada bent to pick up the pieces.

The old servant hovered at the door. He said, ‘I haven’t come in here.’ He did not explain if he feared the dead man’s spirit, thought to remain around its home for forty-nine days, or the warden’s anger.

Akitada said, ‘I’ll be working with your master’s papers. Don’t let me keep you from your chores.’

The old man looked relieved and crept away. Strange, thought Akitada, how many old men and their old servants he had met on this case. First the old lord and his servant, and now the doctor and his. Or perhaps it was not so strange. If loyalty meant anything, then master and servant would grow old together. He thought of Seimei. The bond between them was as strong as blood. The Masuda servant’s passionate hatred for Peony was due to that loyalty. But the doctor’s servant seemed more confused than grief-stricken or angry. Perhaps his claim that he had walked to his cousin’s funeral was untrue.

Enough theorizing. He needed facts.

He prowled around the room, looking at everything but the books and papers. The clothes box held plain and badly worn black robes and under robes, loin cloths, socks with holes in them, and a moldy black cap. Some of the things were good silk twill, but green with age. The dishes were a similar mix. Some were of cheap earthenware and some of fine china, but the china was cracked and chipped. Two pale rectangles on the wall suggested that paintings had hung there once. Otherwise, there was little of a personal nature in the room. No games or musical instruments. Just the broken birdcage.

It supported what he had been told of the doctor: that he had become an individual who cared nothing for personal luxuries, though once he had been well-to-do and had led a different life.

Akitada inspected the shelves of drugs and ointments next. He opened jars and twists of paper and sniffed at the contents. The doctor must have known what all this was, but Akitada was in the dark. Seimei or Tamako might know. Seimei had always dabbled in herbal medicines, and Tamako was an avid gardener who would probably recognize the dried plants that hung from the doctor’s rafters.

He looked at them: bunches of leaves, glaucous or grey, glossy or downy, coarse and smooth, large, small, feathery and spiny, palmate and toothed. He recognized none. Black, white and brown tubers hung among them, twisted and shriveled in their dried death. They reminded him of the neglected garden at home, of the dead wisteria, and of the coldness that had come between him and his wife.

He turned to the books and papers.

The doctor had the medical texts, the Ishimpo, as well as a series of herbals and pharmacological treatises. These, along with the Book of Changes, the Manyoshu, and the four Confucian classics, made up his library. But there were also handwritten scrolls and notebooks. The notebooks were what he had come for. They seemed to cover interesting medical cases and diary entries. Just what he needed. He laid them aside.

In the rolled-up scrolls, each sheet was carefully pasted to the next, while the notebooks were sewn together along one edge. The scrolls contained drawings and poetry. Akitada recognized some of the lines. Apparently, the doctor had liked the poems and had copied them for his own satisfaction. One of the scrolls was devoted to bird studies. It had drawings, as well as observations about avian habits and wise sayings and legends. On the most recent page, he found drawings of a crow and a detailed sketch of its wing. Under the drawings, Inabe had written down the legend of the crow that was sent by the goddess Amaterasu to guide the first emperor and his army to their new homeland.

The doctor’s peculiar obsession with birds seemed harmless, even attractive, but what if it had affected his judgment? He turned to look at the dead crow. Making a face, he picked it up. The flies had done their work thoroughly; the black carcass was dusted with a snow of eggs and crawling with white maggots. Some fell off as he held the large bird by its foot and carried it outside to place it under a shrub. The birds fell silent for a moment. He looked up. Another crow sat on a low branch, its head cocked and its beady eyes staring at him accusingly. ‘I didn’t do it. I’m sorry,’ he said and felt foolish. The crow gave a harsh squawk and flew off. The bird chatter started up again.

And here came the old man, carrying a small sack. When he reached the open area in front of the studio, he shouted, ‘Here it is. Come and eat.’

Another one who talked to birds.

Akitada watched as the servant loosened the knot on the bag and swung it. An arc of golden grain flew out and spread in a shower of kernels across the ground. In an instant, the air was full of feathered bodies and fluttering wings.

Akitada and the old man stood as hundreds of birds landed and scuttled about, chirping and pecking. More and more arrived, alerted by some secret code of their own, until the ground around them was covered with small feathered bodies in all colors and shapes. Then they were done and flew away again in another rush of wings.

Akitada was enchanted.

The old man folded the empty cloth. ‘The last of the rice,’ he said mournfully. ‘In his honor.’

‘But what will you eat now?’

‘Beans.’

He went back to whatever he had been doing, and Akitada looked after him, astonished that this man had thought it more important to honor his master than to fill his own belly. He had been wrong to suspect the man. This also was great loyalty and filled him with sadness. With a sigh, he returned to his work.

The medical notebooks turned out to be nearly incomprehensible. The doctor’s brush strokes were often careless, and worse, he used a form of abbreviated language that meant that Akitada could only make out a few sentences here and there. Part of the problem was the medical vocabulary. Of course, the notebooks might be deciphered by another medical man, but Akitada wanted to locate pertinent material on his own.

It took him well past midday to make out Inabe’s method of dating, and then another while to find the two notebooks that covered the dates of the two deaths. By that time, his stomach growled, his head ached, and his eyes no longer focused. He decided to stroll to the market to get a bite to eat.

The old man had disappeared. Akitada wondered if he was eating his meager meal of beans in some dark corner. The thought made him feel guilty. He decided that he could manage quite well with one bowl of noodles, purchased from a stand. But the noodles were surprisingly tasty and so he ate a second. After months with a listless appetite, he was beginning to take pleasure in food again. This also filled him with guilt. It seemed to him that it signified an end to his grief for Yori. He bought a few rice cakes for the doctor’s servant and chose to go back past Mrs Yozaemon’s.

The boy was outside. Even better, he was playing with the red top. Akitada smiled to see him spin the toy with considerable skill. He was afraid of another rejection and just watched the child from a distance. He was a handsome boy for all his thinness, and the old desire to hold a child in his arms again, to hear him laugh, to feel small arms hugging his neck, was back. He turned to leave.

At the doctor’s house, the old servant accepted the rice cakes with many bows and mumbled thanks, and Akitada returned to his work with a heavy heart and scant interest. He had barely started skimming the entries that dealt with the first smallpox cases when the old man appeared at the open door. He carried two ripe plums on a small footed tray, presenting them to Akitada with a bow.

‘Late ones. Very sweet.’ His eyes strayed towards the rotting plums his master had not lived to eat. ‘Wasps,’ he said worriedly, nodding towards them.

Akitada thanked him and said, ‘There are worse things than wasps. Warden Takechi should be back later. We will ask him when you can clean this room.’ When the old man still stood, looking around sadly, he asked, ‘What are your plans now?’

‘Plans?’

‘I mean if the doctor’s nephew decides to sell this place.’

‘Oh, he’ll sell it.’

‘How do you know?’

‘What the master said. Merchants want gold.’

‘Merchants?’ The old man abbreviated speech as his master had abbreviated his journal entries. Some people became garrulous when they were much alone. Apparently not these two.

‘The master’s family. He didn’t like them.’

‘But I’m told he left this property to his nephew.’

‘Who else?’

To the old man’s mind, family, no matter how unpleasant, came first. Akitada wondered if the property, even in its ruined state, might present a motive for a greedy man. ‘The nephew has visited here?’

‘Once.’

‘When was that?’

‘After the harvest. Spent the night.’ The old man made a face. ‘Quarreled and left.’

‘They quarreled? What about?’

‘Don’t know. The master said, “Good riddance.’”

Akitada sampled a plum. It was delicious. Perhaps he should plant another plum tree. The one in the south garden was too old to bear fruit. This reminded him again of Tamako’s wisteria and other garden matters. He glanced up at the dried herbs. ‘Where did your master get his herbs?’

‘The garden. The monks. And the pharmacist.’

‘There is a herb garden? Where?’

The old man took him. Down a narrow path through the shrubbery, there was a small clearing of cultivated land. A spade lay beside a newly-dug section. The old man said, ‘Time to split the rhubarb.’

‘Rhubarb?’ Akitada was beginning to understand the way his mind worked. He had fed the birds all the rice, and now he was digging the herb garden. He was showing his respect to the dead man.

‘Daiou root. For constipation,’ said his companion.

‘Are any of these plants poisonous? Like warabi, for example?’

The old man gave him a pitying look. ‘Warabi’s not medicine. Doctors heal.’

True enough. Akitada was hunting another murderer altogether. He thanked the old man and returned to his notebooks.

When he read the entry for Peony, he was disappointed and baffled. She was identified only as ‘drowned woman’. The doctor had noted a bruise on her left temple and written ‘not serious’ next to it. And then came the puzzling part, for he had written in the margin, ‘There is no end to my guilt.’ What guilt?

Akitada put the notebook aside and reached for the one that covered the previous year. But no amount of searching produced an entry for the Masuda heir. It was as if his death had never happened, and yet Inabe had treated the young man. He went through the whole notebook again. There was not only no reference to a patient with the flux at the time, but also the pertinent days did not exist in the notebook. He saw no obvious break in the note-taking, no unfinished sentences, but he checked to see if pages had been removed. If so, it had been done so carefully that there was no trace of it.

EIGHTEEN

Fox Magic

After Tora left Little Abbess he made straight for Sadanori’s mansion. As before, the gate stood open, but today no bearers delivered lumber and no carriage waited. At the gate stood one of the monks with a basket hat. When he saw Tora, he placed his wooden begging bowl on the ground between his bare feet and started to play softly on a long, straight bamboo flute. He was not playing very well.

Tora paused to dig out a couple of coppers and drop them in the bowl. The monk lowered his flute and bowed. ‘May Amida bless you.’

‘Your first visit to the capital?’ asked Tora. He gestured at the empty street. ‘Not much traffic here. You’d do a lot better at one of the bridges or in the markets.’

‘Thank you. Do you work in this fine mansion?’

‘No.’ Tora had no time to chat with idle monks. He had his own questions to ask.

A few house servants in their white uniforms and black hats were busy with chores, and in the distance he heard hammering. The builders, apparently, were still busy. The same servant who had discovered Tora on his last intrusion approached.

Tora greeted him like a long-lost friend. ‘Good morning, brother. I was hoping to catch you. We weren’t introduced last time. I’m Tora.’

The other man looked surprised. ‘I’m Genzo,’ he said, nodding a greeting. ‘How’s the job coming?’

‘We ran into a little hitch.’ Tora was pleased with this fabrication. There was always some hitch on a building project. ‘Nothing serious, but the boss wants to know when to expect another inspection. He was hoping Ishikawa was still out of town.’

‘No such luck. He got back last night. But he hasn’t talked to the master yet, so maybe that’ll buy you some time.’

‘Genzo!’

They turned. Sadanori stood at the veranda railing of the nearest building.

Genzo knelt and bowed. ‘Yes, Master?’

Tora remained standing and stared up at his arch enemy. The lord’s fleshy face was nearly round, and its features, a pair of small eyes, a button nose, and small pink lips under a tiny black mustache, struck him as ridiculous. He reached up to stroke his own handsome mustache.

Sadanori’s eyes flicked over him. ‘Who is that person?’ he demanded.

‘He assists the building supervisor, Master.’

‘Oh.’ Sadanori dismissed it. ‘Is Ishikawa back?’

‘Yes, Master.’

‘I want to see him. Now. At the new pavilion.’ Sadanori turned and went back inside.

Tora and the servant waved to each other and took off in opposite directions. Tora trotted towards the pavilion.

It looked almost complete and very pretty with its dark wood, white plaster, and shiny blue roof tiles. A bright red balustrade wrapped around the veranda. The building supervisor stood at the foot of the stairs talking to two men. This time, Tora walked up openly.

‘Morning,’ he said cheerfully. ‘Almost done, eh? Looks nice.’

The supervisor stared. ‘Who’re you?’

‘Oh, I’m from His Lordship’s mother’s household. On a visit to the capital. Thought I’d take a look and see how things are coming along here. Did you know that His Lordship is coming?’

‘What? Now?’

Tora enjoyed the other man’s consternation. ‘Oh, yes. With Ishikawa.’

The supervisor cursed and charged up the steps, while the two workers melted away. Tora grinned and strolled around the building to the back where it overlooked the lake. The piles of lumber had disappeared, as had the stacks of tiles. The tiles covered the roof now and glinted in the sun. Another staircase led to the veranda here, and Tora went up and into the building. He looked for a hiding place, but found only bare rooms. They were quite elegant, beyond anything in the Sugawara household, their columns lacquered red like the balustrade outside, their ceilings decorated with stylized blossoms and birds, and brand-new shutters stood wide open to the gardens and the lake. The smell of fresh paint hung in the air. Tora could hear the supervisor in one of the rooms, shouting, ‘I don’t care if the paint is wet. Cover it up and work somewhere else. Hurry up. Here he comes.’

Tora peered out and saw Sadanori approaching from the main house. The tall Ishikawa walked beside him, and several servants followed. Tora ran down the stairs and ducked under the rear veranda. He wished he could hear Ishikawa’s report, but that was hoping for too much.

He waited patiently and watched the ducks and swans on the lake. Above him, muffled footsteps and voices marked the progress of the inspection. Would they notice whatever the supervisor was covering up? Apparently not. He heard no angry shouts, just some calm muttering. Eventually, the footsteps reached the veranda above his head.

‘The view is charming.’ That was Ishikawa. ‘It will be very pleasant for Your Lordship on moonlit summer evenings.’

Sadanori’s high voice replied, ‘Nothing pleases me any longer.’

The supervisor offered, ‘Perhaps some chrysanthemums can be planted along the lake’s shore, and iris for next spring. It’s perfect as a gentleman’s retreat and also suitable for moon-viewing parties. Your Lordship will spend many happy years here.’

Sadanori said coldly, ‘You may return to your work now.’

‘I hope Your Lordship is pleased with our progress,’ the supervisor pressed.

‘Yes, yes. Run along now.’ Sadanori sounded impatient. Somewhere, a crow cawed.

Ishikawa said, ‘A good place for shooting practice. Having too many birds around destroys the peace.’

Under the veranda, Tora held his breath. Would they have their private talk now?

No. Apparently, they had already exchanged the information Tora was interested in – that is, what Ishikawa had been doing in Otsu. Sadanori now wanted to know what Ishikawa thought of the supervisor.

‘I don’t like the fellow,’ Ishikawa said. ‘I think he takes a cut on every order and pads the workers’ hourly wage list.’

‘Then you should stop him. What do I pay you for?’

Ishikawa laughed softly. ‘Unlike your other servants, I’m a man you can trust. That’s worth a great deal, I should think.’

‘You have gone too far this time.’

‘Your safety was my only concern.’

Silence.

‘That reminds me, how is your lovely daughter?’

‘No!’

Tora jumped a little. Sadanori had practically shouted the word. What was going on?

Above him, Ishikawa laughed again. ‘And to think of the risks I took for you. Sugawara was back in Otsu with that servant of his.’

‘So what?’

‘Don’t forget, there is still another witness.’

‘Your mother?’ There was panic in Sadanori’s voice.

‘Of course not. No, this one is here.’

‘Then you have been careless.’

‘Not at all. I just found out that Sugawara is asking questions about the case.’

‘He won’t find anything.’

‘I disagree.’ Ishikawa moved above Tora’s head. ‘You forget that I know how Sugawara works. He doesn’t give up easily once he catches a scent.’

Silence again. Tora strained his ears. Sadanori grunted, ‘I can stop him.’

‘So can I. There is a woman at Fushimi. She knows how to find her.’

‘I don’t like it. It goes on and on. You take too much on yourself, and things get worse. See if you can manage it another way. We’ll discuss your … fee when all is safe.’

One man’s footsteps receded; Sadanori’s, probably. What was Ishikawa doing? What witness had he been talking about? Tora felt a hollow in the pit of his stomach. What if it was Hanae? But Hanae was safe at the Sugawara house.

Ishikawa finally moved. He went to the stairs and came down. Tora shrank behind one of the supports and watched him walk to the water’s edge. There Ishikawa stopped and looked up into a tree. Suddenly, he scooped up a stone and flung it into the branches. With a loud squawk, a black crow flew up and disappeared. Ishikawa cursed after it and walked away, his face a mask of fury.

More confused than ever, Tora crept from his hiding place and followed. Ishikawa left by the open back gate and turned north.

The Fushimi market adjoined a fox shrine outside the city. Tora was convinced that Ishikawa had killed the doctor in Otsu and planned to kill someone else. Perhaps he should return to Otsu to report, but there was a certain urgency about Ishikawa’s errand that made Tora nervous.

He stayed as far back as he could, mingling with other travelers on the road. Ishikawa was easy to see and not, in any case, suspicious of being followed. He never once bothered to look back.

The shrine attracted many people from the capital, and a village had sprung up around the conical wooded hill sacred to the grain deity. The market stretched along the main street, and at this time, near sunset, it was crowded. Vendors sold food and wine. Ballad singers, monks, and dancers competed for the pilgrims’ coppers and added to the cacophony of the sellers crying out their wares. From the market, a line of red-lacquered torii snaked up the hill towards the shrine to the abode of the three grain deities.

But Ishikawa was not making a spiritual journey. After surveying the crowd, he made his way purposefully along the stands. Tora followed much more closely now. Though Ishikawa was tall, it would be easy to lose him here.

Near the entrance to the shrine grounds, Ishikawa stopped at a stall where a woman was selling combs and fans. The conversation between them was brief. Even at this distance, Tora saw that the woman was nervous. She kept bowing and speaking quickly. After a few sentences, Ishikawa nodded and walked away without buying anything.

Tora was about to approach the stall when a mendicant monk drifted up and talked to the woman. Tora waited, muttering unkind words and scanning the crowd for Ishikawa. He had disappeared.

To console himself, Tora bought a cup of the hot spicy wine. The wine eased his parched throat and was delicious, so he had a second cup. Then he returned to the comb and fan seller. She was middle-aged, but wore the colorful clothes of someone much younger. The paint on her face and her clothes probably meant that she had started life as a ‘fallen flower’ and now eked out a living in this market. She looked glum.

‘If I buy one of your pretty combs for my wife, charming lady,’ Tora said, ‘would you answer a question?’

Few women could resist Tora’s charm when he put his mind to it. This one could. ‘What question?’ she asked listlessly.

He selected a comb. ‘How much for this one?’

‘Fifteen coppers. It’s a very fine comb.’ The answer was automatic. When Tora did not argue, she took the money.

‘A tall man stopped by here a little while ago. Do you know him?’

Her face closed. ‘I don’t remember. A lot of people stop.’

‘Come on,’ Tora pressed her. ‘It just happened. A guy with a sharp face and lousy manners. I saw him. He didn’t buy anything.’ He paused, frustrated by her stubborn silence. ‘Just before that monk talked to you.’

‘He asked about the shrine. The monk asked, too.’

‘He did? Which way did they go?’

She shook her head and turned to another customer.

Tora considered the shrine entrance. Two stone statues of foxes flanked it, their bushy tails reaching skyward. They smirked down at him. The climb was a long one. Tora decided that Ishikawa would not have bothered. He was in the crowd somewhere, probably being followed by the monk wearing a basket hat. That reminded him of the monk in front of Sadanori’s gate. Whichever monk this one was, he was following Ishikawa. Find the monk and find Ishikawa.

He walked up and down between the stalls without seeing either of them. Eventually, he sighed and gave up. The monk was a puzzle. Anyone could hide under one of those basket hats.

Tora’s depression lifted abruptly when he got to the bridge over the Kamo River and saw the monk walking ahead of him. The basket hat bobbed along briskly, and the monk was over the bridge and turning into the warren of streets and alleys before Tora was halfway across.

Cursing the ‘holy’ man’s longer stride, and dodging other travelers, Tora broke into a run. He must not lose his prey again. Luck was with him, and in the light of a shop lantern he caught sight of the basket hat turning south, towards the Willow Quarter. Even better, he was taking a street that was deserted at this time of evening.

Tora increased his speed and had almost caught up when the other man heard his running footsteps and gasping breath and swung around.

![Книга [The Girl From UNCLE 01] - The Global Globules Affair автора Simon Latter](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-the-girl-from-uncle-01-the-global-globules-affair-170637.jpg)