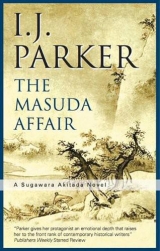

Текст книги "The Masuda Affair "

Автор книги: Ingrid J. Parker

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

THREE

The Dying Wisteria

Akitada stared after her. If she was right about Peony’s child being dead, then the deaf-mute boy belonged to someone else, most likely to the repulsive couple who had dragged him away.

But here was a new mystery: why did Lady Masuda impose such secrecy on her household? Whatever jealousy she might have felt of her husband’s concubine, such arrangements were common enough and accepted. Mrs Ishikawa had known Peony and her son and had been fond of them. Perhaps the elegant lady who had been bent over the account book knew what was in the interest of the Masudas, and the dubious offspring of a former courtesan was best assumed dead.

Whatever had happened, the Masuda problems were not his affair. Yet Akitada paused in his walk to the gate to look back thoughtfully at the Masuda mansion, testimony to the family’s wealth, all of it belonging to an ailing old man without an heir. He wondered about the deaths of the courtesan Peony and her child. He also wondered about the curse killing the male Masuda heirs. Perhaps the years spent solving crimes committed by corrupt, greedy, and vengeful people had made him suspicious. Or perhaps his encounter with the wailing ghost had made him think of restless spirits in search of justice. He was neither religious nor superstitious, but there had been nothing reasonable about the events of the past two days.

For a few moments, the bleak and paralyzing hopelessness that had stifled his spirit lifted because he had stumbled on this mystery.

He asked the old servant waiting patiently beside the gate, ‘When did the young lord die?’

‘Which one, My Lord? Lord Tadayori died last year, and the first lady’s son this year.’ He sighed. ‘Only the two little girls of the second lady are left now, but the old lord cares nothing for them.’

Akitada’s eyebrows rose. ‘How did the grandson die?’

‘The great sickness, My Lord. Many children died from it.’

Akitada’s stomach twisted. His son, that sturdy, handsome bundle of energy, had become a whimpering creature, covered with festering sores, as he watched helplessly. So Lady Masuda had also lost a son. And Peony and her son had died soon after. But their deaths were not clearly accounted for. A picture began to shape in Akitada’s mind.

The story was not unusual. A wealthy nobleman falls in love with a beautiful courtesan, buys out her contract, and keeps her for his private enjoyment in a place where he can visit her often. Such liaisons could last for months or for a lifetime. In this case, there had been a child. Had the younger Masuda really ended his affair or had his death ended it? What if Lady Masuda, after losing both husband and son, had become distraught with grief and jealousy and killed both her rival and her child?

But he was jumping to conclusions without facts. He could not even be certain that Peony’s child had been Masuda’s. He thanked the old man and left.

Crowds were already filling the main streets of Otsu to celebrate the departure of their ancestral ghosts. For most people, death lost its more painful attributes as soon as duty had been observed – when the souls of those who were once deeply mourned had been duly acknowledged and could, with a clear conscience, be sent back to the other world for another year. After dark, people everywhere would gather on the shores of rivers, lakes, and oceans and set afloat tiny straw boats, each containing a small candle or oil lamp, to carry the spirits of the dear departed away. One by one, the lights would grow smaller until they were extinguished.

Akitada’s bitterness had hardened him to human emotions. To his skepticism for supernatural events he had added a cynical distrust for the professed grief of the living. His sympathies were with the dead. What of those ghosts whose lives and families had been taken from them by violence?

Feeling at odds with his world, he returned to the local warden’s office and walked into a shouting match between a portly matron and two prisoners, a nattily-dressed man with a mustache and chin beard, and a ragged youngster of about fourteen. The warden was looking from one to the other and scratching his head.

Apparently, someone had knocked the matron to the ground from behind and snatched a package containing a length of silk from under her arm. When she had gathered her wits, she had seen the two ‘villains’ running away through the crowd. Her screams had brought a constable, who had set off after the fugitives and caught them a short distance away. The package was lying in the street and the two men were scuffling.

The problem was that each blamed the theft on the other and claimed to have been chasing down the culprit.

The ragged boy had tears in his eyes. He kept repeating, ‘I was only trying to help.’ He claimed his mother was waiting for some fish he was to purchase for their holiday meal.

The man with the whiskers was outraged. ‘Lazy kids don’t want to work and think they can steal an honest person’s goods. Maybe a good whipping will teach him before it’s too late.’

The matron, though vocal about her ordeal, was no help at all. ‘I tell you, Warden Takechi, I didn’t see him. He knocked me down and nearly broke my back.’ She rubbed her substantial behind.

The warden shook his head. ‘You should have brought witnesses,’ he grumbled to the constable. ‘Now it’s too late, and what’ll we do?’

The constable protested, ‘Oh come on, Warden. The kid did it. Look at his clothes. Look at his face. Guilt’s written all over him. Let’s take him out back and question him.’

Akitada saw that the boy was terrified. Interrogation meant the whip, and even innocent people had been known to confess to crimes when beaten. He decided to step in. ‘Look here, Constable,’ he said in his sternest official tone. ‘Whipping a suspect without good cause is against the law. And you don’t have good cause without a witness.’

They turned to stare at him. The warden recognized the obstinate gentleman from the night before without much enthusiasm, but he dared not offend an official from the capital. He said, ‘Do you have some information about this matter, sir?’

‘No, but I have a solution for your problem.’

The warden suppressed a sigh. ‘A solution, sir?’

‘Yes. Make them ran the same distance. The loser will be your thief.’

There was a moment’s puzzled silence, and the warden’s jaw sagged a little. Then the matron cried, ‘A truly wise counsel.’ She folded her hands and bowed to Akitada. ‘A person of superior spiritual insight remembers that the Buddha helps the innocent.’

Akitada said dryly, ‘Perhaps, madam, but in this case the thief got caught because his captor was the better runner.’

The warden expelled a sigh of relief. His face broke into a wide grin. ‘Very clever, sir. Let’s go outside.’

They all adjourned to a large field behind the jailhouse, and the constables marked off the proper distance. Akitada watched the preparations with a frown. Taking the warden aside, he said, ‘The culprit may make a break for it. You’d better have your two best runners keep an eye on the man.’

The warden glanced at Whiskers and shook his head. ‘You think he’s the one, eh? You may be right, sir, but with due respect, I’ll have both of them watched. Frankly, I don’t see it. He looks like a respectable citizen, while the kid’s just the type to pull a snatch. This town’s full of half-starved youngsters who make a living by stealing. Travelers passing through are in a hurry and rarely report the thefts. This one made the mistake of picking on a local woman.’ He walked off to alert his constables.

Of course, Warden Takechi knew his town better than Akitada, and the ragged boy did look desperate. On the other hand, Whiskers had lost some of his earlier confidence. He moved his feet nervously and looked around. No, Akitada felt sure he was right about this.

The two suspects took their places and the race was on. The thin boy easily outdistanced the man. Halfway to the finish, Whiskers knew it too and suddenly veered off to make his escape. Several constables were on him in a matter of moments and dragged him back to the office to face charges. The crowd applauded and dispersed, well satisfied with their morning’s entertainment.

The boy came to thank Akitada shyly. ‘I don’t know what I would’ve done without you, sir,’ he mumbled, his eyes moist. ‘Mother’s not as strong as she was. She needs me to run errands and gather wood …’ His eyes widened. ‘The fish! Excuse me, sir.’

Akitada looked after him with a smile.

‘Well, sir,’ said the warden, joining him, ‘I was wrong and you were right about that youngster. I’m much obliged. You saved me from making a bad mistake. Now, how can I be of service?’

Having established such friendly relations, Akitada introduced himself more fully and told him the story of the mute boy, the cat, and the abandoned villa. Warden Takechi’s face grew serious. When Akitada reached the nurse’s account of Peony’s death, he shook his head. ‘I remember. A simple case of drowning. Accident or suicide. They sent for me after she was found. Someone mentioned a boy, but we couldn’t find him, dead or alive. Some think the kappa must’ve got him. Every time someone disappears in the lake, it’s blamed on those water sprites. The dead woman had no friends, and no family either, as far as we could tell. The neighbors thought she was a loose woman from the capital. I can’t see what the Mimuras have to do with that. They live in Awazu and wouldn’t know anybody like that.’

It was a dead end, but Akitada could not leave Otsu without one last attempt to do something for the deaf-mute child. He said, ‘The boy was terrified of them. You must have noticed?’

‘Expected a thrashing for running away,’ the warden grunted.

‘No doubt. He was covered with bruises from, head to toe,’ Akitada snapped.

The warden shook his head. ‘Folk like the Mimuras live hard and raise their young ones hard. It’s what they’ve got to look forward to in life. Prepares them for hardship. Forgive me for saying so, sir, but a gentleman like you would naturally mistake that for abuse. The boy will be all right. They’re raising him to give them a hand with their fishing business. I expect they’ve already got him mending nets and weaving traps when he’s not gutting the catch.’

Akitada shuddered. ‘I gave the man money to feed him properly. Could you have someone check on the boy? If he needs anything, I’d like to know. I’ll leave you information on how to contact me.’

The warden looked dubious, but nodded. ‘As you wish, sir. But it’s best not to spoil them. They get lazy.’

Akitada trusted neither the Mimuras nor the Otsu constabulary and planned to come back to check on the boy himself.

In the office, a constable was taking down information from the thief and the matron. People were waiting, and one of them, a tall and handsome young man in a neat blue robe and black cap, detached himself from a wall.

‘I don’t believe my eyes,’ he said to Akitada. ‘Here you are when I’ve been looking everywhere. I came to check with the warden in case he’d picked up your murdered corpse on the highway.’ He laughed at his joke, flashing a set of handsome teeth and stretching his thin mustache almost from ear to ear.

Akitada said sourly, ‘Nonsense, Tora. You know very well I can look after myself. Why are you here?’

‘Well, you were due back two days ago. Your lady was upset.’

That was probably untrue. Tamako had made it abundantly clear over the past six months that she had lost all interest in him. Most of her anger dated from the death of their son. She blamed him because he had refused to listen to her warnings about the epidemic. But in truth their problems had started before. They had begun growing apart after Yori was born. She had undermined his efforts to teach the boy, and his wishes had no longer seemed to matter to her. After Yori’s death, the bitterness between them had become physical separation. They maintained a coldly polite distance these days.

‘I was delayed,’ he said vaguely, canceling his plan to visit the Mimuras. He could not risk explanations because Tamako would take his interest in the mute child as another example of his indifference to her and their dead son. The fact was that he would have welcomed any excuse to delay the return to his empty home.

It was not literally empty, of course. Beside his wife, it housed his retainers – Tora, Genba, and old Seimei – as well as a cook, a maid, and at times a young servant boy. But with Yori dead, and the bitter recrimination he saw in his wife’s face whenever she looked at him, he felt alone and unwelcome there.

Fortunately, Tora asked no questions. They ate a light meal in the market and then separated. Tora went to get his horse, and Akitada returned to the inn to pay his bill. They met again outside Otsu on the highway to the capital, leaving behind the glittering lake and Otsu harbor.

Tora chattered away as his master rode silently, hardly listening. The road led into the mountains. After a while, Tora gave up and fell silent. They crossed the eastern mountains at Osaka-toge and stopped at the barrier station. The sun was already getting low, and the trees cast long shadows. In these peaceful times the station was unmanned, but small businesses catered to travelers. They watered their horses and stretched their legs. Then, over a cup of wine, Tora tried to find out what troubled his master.

‘Is all well, sir?’ he asked.

‘Why shouldn’t it be?’

‘You haven’t said much. We … I’m thinking it’s time you got back to normal, sir.’

Back to normal? A moment’s anger seized Akitada that Tora should think Yori’s death was so easily brushed aside. He scowled ferociously, saw Tora’s face fall and the pity and concern in his eyes, and sighed instead. ‘It’s not so easy, Tora. Let’s go on. I’d like to get home before dark.’

It was his loss that caused him to yearn so desperately for the child. He wanted to buy the boy from the Mimuras, and his greedy parents would sell him gladly, but he was afraid to take him home to Tamako. But that he could not share with Tora.

They descended the mountains in glum silence. The hillsides opened up before them and revealed the great plain, cradled in green mountains and traversed by wide rivers. In its center, like a jewel, lay the capital, the roofs of its palaces and pagodas glittering in the setting sun. Akitada always paused at this point of the journey to drink in the sight and to let his heart fill with pride at the greatness of the nation he served. He did so now, and Tora came up. He looked cast down.

Akitada felt guilty and said, ‘I came across a curious story in Otsu and almost meddled again. You rescued me just in time.’ He forced a smile and saw Tora’s face light up.

Back on the road, Tora asked, ‘But why not meddle, sir? It might take your mind off … things. And I could help.’

Tora’s enthusiasm for prying into the secrets of total strangers made him a valuable assistant and sometimes a nuisance. It would not do to give him false hopes now. ‘I’m afraid not,’ Akitada said. ‘It’s none of our business, and there doesn’t seem to be a case. It’s a matter of a courtesan who drowned herself and may or may not have killed her child at the same time.’

‘There’s more to it than that, sir, if I know you. Why did she kill herself? And her child! Pitiful, that.’ He shot a cautious glance at Akitada’s face. ‘Boy or girl?’

‘A boy. Five years old.’

Tora sucked in his breath. ‘Do you want to tell me about it, sir?’

Akitada told him what he had learned about Peony and the Masuda family. As they passed the Kiyomizu temple, Tora said enthusiastically, That’s some story. I’ll bet there’s more there than meets the eye. That much money, and all the heirs die.’ He paused. ‘What made you go to that empty villa in the first place?’

Akitada shot him a glance and looked away. ‘Oh, nothing much,’ he said vaguely. ‘To have a look at the lake. The view, and a cool breeze. Did I mention that the nurse is Ishikawa’s mother?’

‘Ishikawa?’

‘You remember the student involved in the cheating scandal at the university?’

‘The one who blackmailed his professor and then tied him to a statue so the killer could cut his throat?’

‘Well, he didn’t intend that.’

‘Brings back memories,’ said Tora. ‘That was when you were courting your lady.’

Akitada regretted having raised the subject.

Tora grinned. ‘You even wrote her a poem and had me take it to her.’

Akitada grunted.

‘A morning-after poem!’

‘That’s enough, Tora.’

They reached the Kamo River and crossed it at the Third Street Gate. It was not far from here to Akitada’s house, and Tora had caught the bleak look on his master’s face and subsided.

The Sugawara residence was substantial and rubbed shoulders with the homes of the wealthy, but it was old and had seen better days. Akitada’s poverty during much of his career had made it impossible to do more than keep a roof over their heads, and sometimes not even that. Recalling the Masuda mansion, Akitada looked at his home now and felt the old sense of inadequacy. He had let his family down. The stable was new, thanks to a case that had brought a generous fee, but the mud and wattle wall that surrounded the property had lost most of its whitewash and sections of plaster, and the roof of the main house needed new shingles. He knew the gardens were badly overgrown, and no doubt things were worse inside. Since Yori’s death he had simply not cared.

Genba opened the gate and greeted them with a broad smile. ‘So you found him, brother,’ he said to Tora, and to Akitada, ‘Welcome home, sir. We were worried.’

Akitada reluctantly accepted the fact that his people might be genuinely fond of him and care about his well-being. As he dismounted, he looked at Genba more closely. If he was not much mistaken, the huge man had lost weight. ‘Are you quite well, Genba?’ he asked.

‘Yes, sir. Why?’

‘You look … thinner.’

Tora glanced at Genba and said, ‘His appetite’s gone, sir. He’s been grieving for Yori. We all have.’

Bereft of speech, Akitada turned to go, then managed a choked, ‘Thank you.’

Tamako was not waiting for him. He went to his study and shed his traveling robe, slipping instead into the comfortable old blue one he wore around the house. Then he went looking for his wife. The house seemed to be empty. In the kitchen, he finally found the frowzy cook. He disliked the woman intensely. Not only was she ill-tempered and lazy, but she had deserted them when Yori had become ill. She had returned later and wept with contrition, claiming that she would starve in the streets if he did not take her back. And he had done so. Now she looked up from chopping vegetables and scowled. ‘So you’re back. I’d better get a fish from the market then.’

The woman was impossible, but being in a softened mood after Genba and Tora, Akitada simply nodded and asked, ‘Where is everybody?’

‘Your lady and the old man are in the garden. Don’t know where the silly girl is.’

The ‘silly girl’ was Tamako’s maid. Akitada went outside. The service yard was neat, thanks to his two stalwart retainers. He could hear their voices from the stable, where they were tending to the horses. He entered the main garden through a narrow gate of woven bamboo.

The trees and shrubs must have put on a burst of new growth over the summer. He looked in dismay at a massive tangle of greenery that reminded him of the courtesan’s garden. It was high time something was done or the garden would swallow the house. Hearing voices, he made his way along the narrow path, its flat stones barely visible any longer, and came on Tamako and Seimei. They had not heard him.

Seimei sat on the veranda steps, huddled in a quilted robe. Akitada frowned. Even after sunset, it was too warm to wear such heavy clothes. He saw how frail the old man had become and remembered with a twinge of guilt how, in his raving grief over the loss of his son, he had questioned the justice of a fate that snatched the youngest and let the old survive.

Tamako wore an old blue-and-white patterned cloth robe. She had turned up its sleeves and tucked the skirt into her sash so that he could see her trousers underneath. Her long hair was twisted up under a blue scarf. She was cutting dead wood from the wisteria vine. A large pile lay beside her.

It was a day for uncomfortable memories. Akitada had fallen in love with Tamako when she had worn a similar blue cloth gown. They had been sitting under a wisteria-covered trellis in her father’s garden. Under the ancestor of this very same wisteria. And the poem Tora had carried to her the morning after their first night together had been tied to a wisteria bloom from that plant.

‘Why don’t you let Genba and Tora do that?’ he asked sharply.

They both jumped. Seimei rose shakily to his feet and bowed, crying, ‘Welcome home, sir. We were worried.’

Tamako said nothing. She gave him a searching, earnest look, then turned away.

He stared at her back. ‘There is no need for you to do such heavy work,’ he said. ‘I can still afford to hire people.’

‘It is dying,’ she murmured vaguely, touching the shriveled twigs that remained on the plant. ‘I have tried, but it keeps dying. A little more each day.’

‘Nonsense. It just needs water. Or something.’

‘There has been a lot of rain.’

Seimei sighed. ‘Too much rain. It causes rot, and healthy things shrivel up and die.’

Tamako turned. They both looked at Seimei and then at each other and wondered if the old man was talking about the wisteria.

![Книга [The Girl From UNCLE 01] - The Global Globules Affair автора Simon Latter](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-the-girl-from-uncle-01-the-global-globules-affair-170637.jpg)