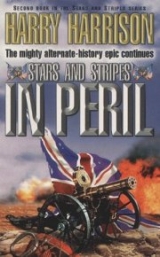

Текст книги "Stars and Stripes In Peril"

Автор книги: Harry Harrison

Жанр:

Альтернативная история

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

PERFIDIOUS ALBION

Brigadier Somerville waited on the quayside, holding his hat to prevent it from being blown away. The bitter north wind whipped spray and rain across his face, more like December than May here in Portsmouth. The fleet, at anchor, were just dim shapes in the harbor. Dark hulls with yardarms barely visible through the rain. Only one of the ships was bare of masts, with just a single funnel projecting above her deck.

“Valiant, sir,” the naval officer said. “Sister ship of the Intrepid which will be arriving tomorrow. Her shakedown cruise was most satisfactory I understand. Some trouble with leaks around the gunshields – but that was soon put right.”

“Ugly thing, isn’t it? I do miss the lines of the masts.”

“We don’t,” the commander said with brutal frankness. “I had friends on Warrior. She went down with all hands. We are determined to see that shan’t happen again. Valiant can equal or better the Yankees. We have learned a thing or two since Monitor and Virginia fought each other to a draw. I saw that battle. My ship was stationed outside of Hampton Roads at that time for that very purpose. It seems a century ago. The first battle of iron ship against iron ship. Naval warfare changed that day. Irreversibly and forever. I have been a sailor all my life and I love life under sail. But I am also a realist. We need a fighting navy and a modern navy. And that means the end of sail. The ship of war must now be a fighting machine. With bigger guns and far better armor. That was the trouble with Warrior. She was neither flesh nor fowl nor good red herring. Neither sail nor steam, but a little of both. These new ships of war have been built to the same pattern – but with major improvements. Now that the sails and masts are gone, along with all their gear and sail lockers, there is more room for more coal bunkers. Which means that we can stay at sea that much longer. Even more important is the fact that we can now cut the crew requirements in half.”

“You’ve lost me, I am afraid.”

“Simple enough. Without sails we don’t need veteran sailors to climb the masts to set the sails. There is also the rather dismal fact that aboard Warrior sails and anchor were lifted manually, for some forgotten admiralty bit of reasoning. We use steam winches now that do the job faster and better. Also, although it will be small solace to those who died in Warrior, we have redesigned the citadel, the armored box that was to protect the gun batteries. But it didn’t. We have learned a thing or two since then. The Yankee guns punched right through the vertical armor plate. The plate is thicker now – and we have learned as well from the design of Virginia. You will remember that her armor was slanted at a forty-five-degree angle, so solid shot just bounced off of her. So now our citadel also has slanted sides. And, unlike, Warrior, we also have armor plate covering the bow and stern. They are real fighting ships that can better anything afloat.”

“I certainly hope that you are right, Commander. Like you, I believe that we in the military must change our ways of thinking. Adapt or die.”

“In what way?”

“Small arms, for one instance. During the past conflict I watched the Americans shoot our lines to pieces, over and over again. I believe we had the best soldiers, certainly the best discipline. Yet we lost the battle. The Americans fired faster from their breech-loading rifles. If – when – we go to war again we must have guns like those.”

“I’ve heard of them, yes,” the naval officer said. “But I value discipline more highly. Certainly we need it aboard ship. It is the disciplined and highly trained gun crew who will not wilt under fire. Men who will continue serving their gun irrespective of what is happening around them. The marines too. I’ve watched them train – and I have watched them in combat. Like machines they are. Load, aim, fire. Load, aim, fire. If they had these fancy breech-loaders, why they could fire at any time they pleased. No discipline. They would surely waste their ammunition.”

“I agree with your guncrew training. Discipline shows under fire. But I am sorry to disagree with your attitude towards repeating rifles. When soldiers face soldiers the ones who put the most lead into the air towards the enemy will win. I assure you, sir, for I saw it happen.”

The steam launch sounded its whistle as it approached the quay and the two men waiting there to board it. A companionway was slung down from the boat and Somerville followed the naval officer down into the cramped cabin. It stank of a chill fug, but at least it offered protection from the rain as they puffed out into the harbor. A few minutes later the launch tied up to a landing stage. They hurried across it and climbed the companionway that gave them access to the new warship. The commander called out to one of the sailors on watch and instructed him to take Somerville below to the captain’s quarters.

Aboard Valiant the luxurious space of the captain’s day room was in marked contrast to the cabin of the launch that had brought him here. Coal-oil lamps in gimbals cast a warm light on the dark wood fittings and on the leather upholstered chairs. The naval officers turned from the charts they were looking at when the army officer came in.

“Ah, Somerville, welcome aboard,” Admiral Napier said. A tall man with magnificent mutton-chop whiskers, the top of his head almost brushing the ceiling. “I don’t believe you have met Captain Fosbery who commands this vessel. Brigadier Somerville.”

There was a decanter of port next to the charts and Somerville accepted a glass. The admiral tapped the chart.

“ Land’s End, that is where we will be two days from now. That is our rendezvous. Some of the cargo ships, the slower ones under sail, are already on the way there at the present time. We shall sail tomorrow after Intrepid arrives. I’ll transfer my flag to her because I want to see how she maneuvers at sea.”

Somerville studied the chart and nodded. “Does every ship know our destination?”

The admiral nodded. “They do. Each vessel has been issued with its own individual orders. Ships do get separated in bad weather. And these transports are all heavily laden with cannon so we are sure to have stragglers.” He pushed the chart aside and slid over another one. “We shall all rendezvous here, out of sight of land and away from the usual shipping lanes. And certainly away from the state of Florida. Sixty-six degrees west on latitude twenty-four north.”

“The various ships involved, they have known this destination – for how long?”

“At least the past three weeks.”

“That will be fine, very fine indeed.”

They both smiled at that, Admiral Napier even chuckling to himself. Captain Fosbery noticed this and wondered at its significance – then shrugged it off as one of the foibles of high command. He knew better than to ask them what appeared to be so funny.

“Another port, sir?” Fosbery asked, noting the army officer’s empty glass.

“Indeed. And a toast perhaps? Admiral?”

“I heartily agree. What shall we say – a safe voyage. And confusion to the enemy.”

This time the two officers did laugh out loud, then drained their glasses. Captain Fosbery reminded himself again that he was too lowly in rank to dare to ask them what the joke was.

It was a chill and rainy afternoon in England. Not so in Mexico, far across the width of the Atlantic Ocean. It was early morning there and already very hot. Rifleman Bikram Haidar of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles did not mind the heat too much. Nepal in the summer could be as hot as this – even hotter. And Bombay, where they had been stationed before they came here, was far worse. No, it wasn’t the tropical heat but the endless digging that was so bothersome. If he had wanted to stay at home and be a farmer, he could have spent his life digging in the fields like this, with a shovel and a hoe. But never for a second had he wanted to be a farmer. Since he had been a small boy he had always known that he would be a soldier like his father, and his father before him. He remembered how his grandfather would sit by the fire in the evening, smoking his pipe. Sitting with his back straight, just as erect as he had been fifty years before. And the stories that he told! Of strange countries and strange peoples. Battles fought and won. Tricks that had been played, good times that the regiment had enjoyed together. Wonderful! He never, not for a single instant, had even the tiniest doubt that he wanted to be a soldier of the Queen. He had no doubts now. He just did not like the digging.

He felt better when the jemadar called out to him and the others nearby.

“Leave the digging and get some of this undergrowth cut and out of the way. So the axe men can get at the trees.”

Bikram happily drew his kukri and trotted with the other Gurkhas, past the rows of laboring men. Behind them the dusty road curved around the side of the hill, crossed a ravine on a wooden bridge that the engineers were just completing. Ahead the growth had been cleared and soldiers of the Bombay Rifles were chopping down the trees that blocked the way. Beyond them was the jungle.

Bikram had started to hack at a trailing vine when they heard a distant rattle from their rear.

“Is that gunfire, jemadar?” he asked.

The jemadar grunted agreement; he had heard the sound of guns often enough in the past. He looked back down the road to the spot where their muskets were neatly stacked; quickly made up his mind.

“Get your guns—”

He never finished speaking as a ragged volley of shots sounded from the depths of the jungle before them. He fell, blood pouring from his torn throat. Bikram hurled himself to the ground, crawled forward beneath the shrubbery, his kukri extended. More shots tore the leaves over his head, followed by the sound of running men ahead of him. Then nothing. There was shouting from behind him. He lay still for a moment. Should he follow the attackers? One man armed only with his sharp blade. It did not seem to be a wise thing to do. But he was Gurkha and a fighting man. He was just starting after the ambushing gunmen when there were more shouted commands and the sound of a bugle.

Assembly. Reluctantly, still keeping low, he went back to his company – dodging aside to avoid the officer on his rearing horse. The horseman was followed by gasping soldiers of the Yorkshire Regiment, the 33rd Foot. At his command they halted and formed a line. Aiming their guns at the silent forest.

As they were doing this more firing sounded back down the road. The officer cursed loudly and fluently.

By the time the Gurkhas had returned to their guns and formed up, the firing had completely died away. The wounded and the dead were carried back to camp. Their losses were slight – but all work on the road had stopped for the good part of an hour. Ever so slowly it began again. Despite everything, the armed attackers, the heat, the snakes and insects, the road was being built.

Gustavus Fox had hints and rumors, but no hard evidence. Yes, the British were putting together a naval force of some kind. He had received reports from a number of his operatives in the British Isles. Something was happening – but no one seemed to know what. Until now. He spread the telegram out on the desk before him and read it for perhaps the hundredth time.

ARRIVED BALTIMORE BRINGING NEWSPAPER ROBIN

“Robin” was the code name of his most astute agent in the British Isles. An impoverished Irish count who had been to the right schools and sounded more English than the English. Nor was he ashamed to take money for working for the American cause. He was always reliable, his information always correct. And “newspaper” was the code word for a document. What document was worth his leaving England at this time?

“Someone to see you, sir.” Fox jumped to his feet.

“Show him in!”

The man who entered was slim, almost to the point of emaciation. But he had a reputation as a swordsman, and it was rumored as well that he had left Ireland under a cloud, after a duel.

“You are a welcome sight, Robin.”

“You too, old boy. Been a devilish long time. I do hope that your coffers are full for I had to pay dearly for this.” He took a folded paper from his pocket and handed it over. “Copied in my own hand from the original, which I assure you was the real thing. Admiralty letterhead and all.”

“Wonderful,” Fox mumbled as he scanned the document. “Wonderful. Wait here – I won’t be long.” He was out the door without waiting for an answer.

The Cabinet meeting was in progress when John Nicolay, Lincoln’s first secretary, knocked on the door and let himself in. He looked embarrassed at the silence that followed, the heads turned to look at him.

“Gentlemen, Mr. President, please excuse me for this interruption – but Mr. Fox is here. A matter of some urgency he said.”

Lincoln nodded. “When Gus says urgency I guess he means it. Send him in.”

Fox entered as the President finished speaking: he must have been standing just behind Nicolay. His expression was set, his face grim. Lincoln had never seen him like this before.

“Some urgency, Gus?” he asked as the door closed.

“It is, sir, or I would not have come here and interrupted your meeting at this time.”

“Out with it then, as the man said to the dentist.”

“I have here a report that has just come in – from a man in England I trust implicitly. His information, in the past, has always been most exact and reliable. It verifies some other information I received last week that was more than a little vague. This one is not.”

“Our friends the British?”

“Exactly so, sir. A convoy has left England. Cargo and troop ships guarded by at least two ironclads. I have known about this for some time – but have only now discovered their destination.” He held up the copy of the British naval orders. “Their destination appears to be in the West Indies.”

“There is a lot of ocean and plenty more islands out there,” Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles said. “How can you be sure?”

“There is that to be considered, Mr. Secretary. But the nature of the cargo seems to indicate their destination. Cannon, gentlemen. All of these ships are laden with heavy cannon that can be mounted on land, for defense…”

“The Bahamas!” Welles said, leaping to his feet. “The bases we took from the British – they want them back. They will need them for coaling ports again for any proposed action in the Gulf of Mexico.”

Fox nodded. “That is my belief as well. And I must add, and what I say must not leave this room, that I have physical evidence as well. Let us say that some English captains are less honest than others. One of my representatives has actually seen a ship’s orders and made a copy of it. I have it here. A rendezvous close to the Bahamas.”

“What forces do we have there?” Lincoln asked. All eyes were on the Secretary of War.

“The islands are lightly held,” Stanton said. “We demolished all the defenses after we seized them from the enemy.”

“The Avenger!” Welles said. “She’s tied up at Fortress Monroe. Should I contact her?”

“You should indeed. Send her to the West Indies at once, with a copy of the orders for the British rendezvous,” Lincoln said. “While we decide what we must do to defend ourselves against this new threat. This is grave news indeed. Would someone find a chart of the area?”

The Secretary of the Navy found the chart and spread it out on the table. They gathered around, peering over his shoulder as he talked.

“The guns were removed from the defensive positions and forts on the islands, here and here. The British troops are gone and we have some small garrisons taking their place. We never thought that they would return…”

“If they do retake the islands,” Lincoln asked, “what will it mean?”

“A foothold in the Americas,” Welles said grimly. “If they dig in well it won’t be as easy to root them out this time. They know now what to expect. If their guns are big enough we will have the devil’s own job to do. The coaling ports will enable them to reach Mexico easily. With more than enough coal left for an invasion along our Gulf coast.”

“Make sure that Avenger knows how important this mission is,” Lincoln said. “She is to proceed at her top speed. With her cannon loaded and ready. God only knows what she will find when she gets there.”

THUNDER BEFORE THE STORM

After much consideration Judah P. Benjamin finally decided that he would just have to do the job himself. He had his horse saddled while he was still eating breakfast. When he rode out he did not go to his office in Washington City; instead he turned towards Long Bridge and went across it to Virginia. He had considered all of the possibilities, all of the courses open to him. The easiest thing to have done would have been to have written a letter. Easy, but surely not very effective. Or he could have sent one of his clerks – or even someone from the Freedmen’s Bureau. But would they be convincing enough to get the aid he so desperately needed? He doubted it. This was one task he had to do on his own. His years in the business world, then in politics, had taught him how to be most persuasive when he had to be. Right now – he had to be.

It was a pleasant day and only a short ride to Falls Church. The fields he passed were lush and green, the cows rotund and healthy. The first sprouts of corn were already coming up. Although it was still early when he reached the town, there were already three gray-bearded men sitting in front of the general store, sucking on their pipes. He approached them.

“Good morning,” he said and touched the brim of his hat lightly.

The men nodded and the nearest said “How, y’all,” then launched a jet of tobacco juice into the dust of the street.

“I am looking for the encampment of the Texas Brigade and would greatly appreciate directions.”

They looked at each other in silence as though weighing the import of the question. Finally the one who appeared to be the oldest of the trio took his pipe out of his mouth and pointed with the stem.

“Keep on like directly you doin’. Then after you pass a copse of cottonwoods, you keep an eye out for their tents. Off over to the right a tad. Can’t miss ’em.”

Benjamin touched the brim of his hat again and rode on. About a quarter of a mile down the road and past the cottonwood trees. There were the tents all right, neat rows of them stretching across the field. In front of the larger company tent there were two flagstaffs as well. One flying the stars and stripes – the other the stars and bars. The country was reunited right enough, but still seemed to be unable to come to a decision about the symbols of the past.

The soldier on guard turned him over to the officer of the day who managed a salute when he heard Judah P. Benjamin’s name.

“Mighty proud to make your acquaintance, suh. A’hm sure that General Bragg will be delighted to speak with you.”

Delighted or no, Bragg invited him into his tent. He was a large man, his skin burnt brown like most Texicans. After he climbed to his feet he extended his hand. He had his boots on, as well as his uniform trousers, but wore only a long-sleeved red undershirt above that. He did not take off his wide-brimmed hat when he sat down again.

“Join me with some fresh-brewed coffee, Mr. Benjamin, and tell me how things are going in Washington City these days.”

“Good, about just as good as might be expected. Southern people are coming back now, and it is a far livelier place than it was just after the war. There are parties and soirees and suchlike, something going on all the time. Very exciting if you like that kind of thing.”

“We all like that sort of thing, as I am sure you will agree.”

“I do indeed. If you have the time would you consider attending one of these affairs? I am having an open house this very week. Mostly politicians of course. But I would dearly love to have some military officers there to remind them that the army saved this nation – not their speeches.”

“You are kind indeed – and I am much obliged. I shall come and be most military at all times. And while I am in the city I would like to see for myself what damage was done by that British raid.”

“Very little to see now. The Capitol is being repaired where the British burnt it, and there are almost no signs left of their invasion.”

They made small talk for a bit in a relaxed Southern manner. Benjamin was half finished with his coffee before he approached his subject in an oblique way.

“You and your troops settled in nicely here?”

“Happy as a June bug in a flower patch. Getting a little restless, maybe. Some talk about how they signed on to fight, not sit on their backsides.”

“Ahh, that’s fine… fine. How long are they enrolled for?”

“Most of them got about six months to go. With the war ended they kind of yearnin’ to see Texas again. That’s something I can understand myself.”

“Understandable, surely. But there is something that they could do. I wonder then if your men, and you, would be interested in rendering a further service to your country.”

“Fighting?” General Bragg asked, a sudden coolness in his voice. “I thought that the war was over.”

“It is, of course it is. But there is now the matter of seeing that it stays that way. That we keep the peace. You know about the Freedmen’s Bureau?”

“Can’t say that I do.”

“It’s a bureau that helps the former slaves. Pays their owners for their freedom. Then sort of guides them along in their new lives. Helps them getting jobs, getting land for farming, that sort of thing.”

“Seems a good idea, I suppose. I guess that you have to do something with them.”

“I am glad to hear that because, as you can readily imagine, there are some people that don’t agree with this work. People who don’t believe that the Negroes should be educated.”

“Well, I can truthfully say that I am of two minds about that myself. Not that I ever owned any slaves, mind you. But they might get above themselves, you see.”

Benjamin took his kerchief from his pocket and wiped his face. The sun was beating down on the tent and it was getting hot. “Well, it is the law, you might say. But unhappily there are some people who put themselves above the law. The slaves are free, their former owners have been paid for their freedom, so that should be that.”

“But it isn’t,” General Bragg said. “I can understand that. A man spends his life looking at the colored as a piece of property, why he’s not going to change his thinking just because he got paid some money. You can’t change the way things work overnight, that’s for certain.”

“There is much truth in what you say. But the law is still the law and it must be obeyed. In any case, there have been some threats of violence, while some of the Freedmen’s Bureaus have been burned. We don’t want the situation to get any worse. So we want to assign soldiers to the Freedmen’s Bureau to make sure that the peace in the South is kept. Which is why I am here to talk to you, to ask you to aid me in keeping the peace.”

“Isn’t that the work of the local lawmen?”

“It should be – but many times they don’t want to cooperate.”

“Don’t blame them.”

“Yes, neither do I, but it is still the law. Now you know, and I know, that the one thing we cannot do is to have any soldiers from the North come down here to do this kind of work. Keeping the peace.”

The general snorted loudly and called for more coffee, cocked his head and looked at Benjamin. “That sure would start the war all over again, I reckon. Start it even faster if you used black Yankee troops.”

“But we could use Southern soldiers. Texas soldiers by choice. The men of your brigade fought hard and well for the South and no man will doubt your loyalty. But there are few slaves in your state, even fewer cotton plantations. My hope is that Texicans would be more, say, even-handed in the application of the law. And certainly none in the South would fault their presence.”

“Yes, it’s a thought. But I can envisage a lot of problems coming up, a passel of problems. I think that I’ll have to talk to my officers about this first before I make any decisions. Maybe even speak to the men.”

“Of course. The men cannot be assigned against their will. And when you talk to them, please tell them that, in addition to their army pay, there will be separate payments from the Bureau. These men will be going home soon and I know they will surely like to take back as many silver dollars as they can.”

“Now that is an argument that makes powerful sense.”

“I’m pleased to hear that, General. Will it be all right if I send you a telegram tomorrow to find out about your decision?”

“You do that. Should know something by then.”

Judah Benjamin was buoyed by hope as he rode back to the capital. The road to peace and Negro freedom was proving not to be a very smooth one.

Jefferson Davis was very much of the same mind. The end of the War Between the States, the end to all the killing, had been a noble effort that had come through in the end. The killing had been stopped, that at least had been done, but it had been replaced by what was, in the least, becoming an uneasy peace. He must do something about it.

His wound had healed well, though he had little strength in his left arm; the surgeon had cut away muscle and tissue to get the pistol ball, and cloth, out of his wound. But the fever was a thing of the past now and his strength grew daily. Nevertheless the train trip to Arlington had been tiring. But Robert E. Lee had met him at the station himself, driving the buggy. The United States Government, which had seized Lee’s home because of unpaid taxes, had returned it to its rightful owner, slightly the worse for wear, at the war’s end. It had now been restored to its original condition.

Jefferson Davis had passed a restful three days before he felt up to riding again. Always a keen equestrian, the thing that he had missed most was his daily ride. Now that he could sit a horse again he felt stronger with every passing day. His hosts seemed pleased to see his health improving daily and he was aware of this fact. But he also did not want to wear out his welcome. Finally he was strong enough, he was sure, to ride from Arlington to the White House. He looked up from his breakfast as Lee came in.

“I had the gray mare saddled up,” Lee said. “She’s calm and sensible and a bit like riding in a rocking chair.”

“I thank you kindly. I’m still not fit enough to ride a sprightly mount like your Traveller. I think that I’ll be on my way now before the day heats up.”

The weather was fine, the sun warm – and despite the twinges of pain he still felt from his wound – he had the strength of a man on a mission. And the mare was slow and as steady as promised. He crossed the Potomac and turned down Pennsylvania Avenue. Apparently he must have been seen as he came up the drive, because as he approached the Executive Mansion, Lincoln himself came out on the steps to greet him.

“You are looking spry and fit, Jefferson. Seeing you here like this is the best news I could have ever received.”

“Better every day, Abraham, always better.”

Lincoln beckoned and one of the guards hurried forward to help Davis to dismount from his horse.

“Come into the green room and avoid the stairs,” Lincoln said. “Can I offer you some refreshment?”

“At this time of day I think a cup of tea would be most satisfactory.”

“Do you hear that, Nicolay?” Lincoln called to his secretary who was waiting in the hall. “And see that no one disturbs us after that.”

Jefferson Davis drank his tea – then spoke. “How goes this British intrusion into Mexico? I read the reports in the papers, but they are all wind and no meat. The newspaper writers wrap themselves in the flag and go on about the Monroe Doctrine and manifest destiny. But they seem to be a little light on facts.”

“That’s only because they have none. The surrounding jungle keeps news out and the enemy safe within. But all in all I would say that things are going as well as can be expected at this stage. It is not public knowledge yet, but guns and ammunition are reaching the Mexican army and their irregulars. On the diplomatic front things go much more slowly. Emperor Napoleon insists that they are in Mexico at the invitation of the people and makes reference often to the money owed to them. He wants the world to believe that the Emperor Maximilian was asked to rule by the people of Mexico. I doubt if anyone – other than Maximilian himself – believes such tosh.”

“And here at home? How goes the peace?”

He asked the question in a flat voice, but there was a tension behind his words that could not be concealed. Lincoln put his cup down and hesitated before he spoke.

“I wish I could tell you that everything is fine – because it is not. Though there has already been much progress right across the country, and particularly in the South. The economy is booming with the new mills and factories, the railways rebuilt, new rolling stock coming out of the train yards. New warships launched, others being built. But, as always, Congress is being difficult about the appropriations bill. And there is a strong movement to dispatch troops to Mexico to throw the British out. And the British seem to be up to their old tricks – sending arms to the West Indies, planning to retake the islands.”

“That’s all politics. I wasn’t talking about that. I was talking about the nigras and the South.”

Lincoln sighed. “I thought that you might be.”

“People come to see me. They tell me things that I don’t like to hear. The freed slaves are getting very uppity. They got schools going in their churches now, with teachers from the North teaching them how to read and write.”

“That is not against the law.”

“Well it should be. Who is going to work the fields while they are all in their schools and such and dilly-dallying and telling each other how great they are? And when they’re not in school they’re out there plowing a couple of acres for themselves. While the cotton just hangs in the fields and rots.”

“That is what the Freemen’s Bureau is for. They can aid the planters as well as the Negroes, they can find field hands…”