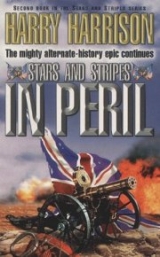

Текст книги "Stars and Stripes In Peril"

Автор книги: Harry Harrison

Жанр:

Альтернативная история

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

“How are the roads?” General Lee asked.

“Excellent. Or as excellent as any road is in Ireland.”

Lee studied the map closely. “Then we will have trains and good roads – and it looks to be no more than fifty miles from Belfast. Good troops can march that in a day, a day and a half in the most. We will take your advice under serious consideration,” Lee said, then pointed his finger at the surgeon. “With General Meagher’s approval you now have a new posting. My staff surgeon is about to have family problems and will return home on leave. I would like you to take his post until he returns. Which is going to be a very long time. I will need all of your medical skills – but also all of your political knowledge as well. You shall be both a medical officer and a political officer. Can you do that?”

“It will be my great pleasure, General Lee.”

“Take him,” Meagher said. “Keep him safe and return him after the war.”

LOCKED IN COMBAT

London had been miserable for over a week. Unseasonal storms and high winds had lashed the capital and drenched her citizens. William Gladstone, who hated the damp, had huddled next to the fire in his study for most of that time. Palmerston’s orders had been peremptory and specific. The military needed more money: there was the need to raise taxes. The stone that was the British public must be squeezed again. Squeezed for money, not for blood.

When Gladstone awoke this Monday morning it was with a feeling of dread. This was the day of the Cabinet meeting. The Prime Minister would be sure to be displeased at the new taxes. Nothing unusual; he was always displeased. Not only a Cabinet meeting, but a dreaded visit to Her Majesty afterward. She could be infinitely trying these days. Either introspective and mourning her dear Albert – which was bearable, though terribly boring. Better still than the other extreme. The reddened face and the shrill screams. Not for the first time did he remember that, after all, she was the granddaughter of mad German George.

Yet when his manservant opened the curtains Gladstone’s spirits, if they did not soar, were lifted more than a little bit. Golden sunshine poured into the room; a blackbird sang in the distance. After breaking his fast he was in a still better mood. He would leave his carriage behind and walk, that is what he would do. It was a pleasant walk to Whitehall from his rooms here in Bond Street. He poured himself another cup of tea and sent for his private secretary.

“Ah, Edward, I have a slight task for you.” Hamilton nodded in expectant silence. “Those budget papers we have been working on. Put them together and bring them to the Cabinet Room for me. Leave them with Lord Palmerston’s secretary.”

“Will you want the navy proposals as well?”

“Yes, surely. Pack them all up.”

The sun was shining radiantly through the fanlight over the front door. Gladstone put on his hat, tapped it into position, picked up his stick and let himself out. It was indeed a glorious day.

The pavements were crowded, particularly in Piccadilly, but the crowd was in a friendly mood: the sun cheered everyone. Further on, near Piccadilly Circus, a man was holding out to the passers-by. His clothes revealed him to be a Quaker, one of that very difficult sect. Gladstone had to listen to him, whether or no, since the people in the crowded street were scarcely moving.

“…violates God’s will. Plague may be a curse upon mankind for living in evil ways, but plague cannot be avoided by an act of will for it is indifferent to class or rank. The lord in his castle will fall victim, just as surely as the peasant in his hovel. But war, I tell you, war is an abomination and a sin. Is this the best we can do with the intelligence God gave us, with the money that we have earned by the sweat of our brow? Instead of food and peace we spend our substance on guns and war. The citizens of the Americas are our brothers, our fellows, fruit of the same loins from whence we ourselves have sprung. Yet those who would be our masters urge us to spill our blood in attacking them. The scurrilous rags we call newspapers froth with hatred and calumny and speak with the voices of evil and wrongdoing. So I say unto you, disdain from the evil, speak to your masters that war is not the way. Is it really our wish to see our sons bleed and die on distant shores? Cry out with one voice and say…”

What the voice should say would never be known. The strong hands of two burly soldiers plucked the man down from his box and, under a sergeant’s supervision, carried him away. The crowd cheered good-naturedly and went about their business. Gladstone turned down a side street and away from the crowd, disturbed by what he had seen.

Was there really an antiwar movement? Certainly there were grumbles over the increasing taxes. But the mob did love a circus and read with pleasure about the glowing – and exaggerated – prowess of British arms. Many still remembered the defeats in America and longed for victories by strength of arms to remove the sour smell of that defeat. At times it was hard to assess the public mood. As he turned into Downing Street he joined Lord John Russell, also going in the same direction.

“Ready for the lion’s cage, hey?” Gladstone said.

“Some say that Palmerston’s bark is worse than his bite,” the Foreign Secretary answered with a worldly flip of his hand.

“I say that bark and bite are both rather mordant. By the way, on the way here I heard a street speaker sounding off at the evils of our war policy. Do you think he was alone – or is the spirit abroad that we should be seeking peace?”

“I doubt that very much. Parliament still sides with the war party and the papers scream and froth for victories. Individuals may think differently, but, by George, the country is on our side.”

“I wish that I had your assurance, Lord John. Still, I find it disturbing, disturbing indeed.”

“Vox populi is not always vox dei, no matter what you hear to the contrary. The voice that matters is that of Palmerston, and as long as this party is in power that is the only voice that you will hear.”

It was indeed a voice that demanded respect. As the Cabinet assembled around the long table Lord Palmerston frowned heavily down at them and rubbed his hands together. He was used to bullying his Cabinet. After all he was the Prime Minister, and he had appointed every one of them. So their loyalty must be to him and him alone. Parliament could be difficult at times, but the war spirit was running high there, so that they could usually be cajoled into backing his proposals. And then, of course, there was always the Queen. When Prince Albert had been alive there had been scenes and difficulties when Palmerston had made unilateral decisions without consulting the Royal Couple. As he had done in the Don Pacifico affair. David Pacifico was a Portuguese Jew born in Gibraltar. He became a merchant in Athens. His house there was burned down during an anti-Semitic riot. On very questionable grounds, he sued the Greek government – with little result. Without consulting the Queen, or her consort, Palmerston had organized an attack on Greece on Don Pacifico’s behalf. To say that the Queen was disturbed by this was an understatement. But that was happily a thing of the past. After Albert’s death she had retired more and more inside herself. Yet sometimes she had to be consulted, lest she lost her temper over some implied insult, or more realistically, a major decision taken without her knowledge. This was now such a time. She must be consulted before the planned expansion was undertaken.

This meeting was like most Cabinet meetings these days. Lord Palmerston told them what he would like to have done. After that the discussion was about how it should be done – and never any discussion whether it should be done at all. This day was no exception.

“Then I gather that we are all in agreement?” Palmerston said testily to his Cabinet, as though any slightest sign of disagreement would be a personal insult. At the age of seventy-nine his voice had lost none of its abrasiveness; his eyes still had the cold, inflexible stare of a serpent.

“It will need a great deal of financing,” the Chancellor of the Exchequer, said, rather petulantly. Palmerston waved away even this slightest of differences.

“Of course it will.” Palmerston dismissed this argument peremptorily. “You are the chap who can always raise the money. That is exactly why I need you today at this particular tête-à-tête,” he added, completely misusing the term. Which, of course, meant just two people, head-to-head. Gladstone chose not to correct him, knowing the Prime Minister’s pride in his ignorance of any language other than English. But the thought of visiting the Queen took the sunlight out of his day.

“You know my feelings,” Gladstone said. “I believe that Her Majesty is one of the greatest Jingoes alive. If we but mention Albert and the Americans in the same breath we can keep the war going for a century. But, really, her interference in affairs of state is enough to kill any man.”

Palmerston had to smile at Gladstone’s tirade because the hatred was mutual. The Queen had once referred to him as a half-mad firebrand. They were a well-matched pair, both self-absorbed and opinionated. “Perhaps you are right – but still we must at least appear to consult her. We need more money. While you do the sums, Admiral Sawyer here will make her privy to the naval considerations involved.”

The admiral had been invited to the Cabinet meeting to present the views of the Royal Navy. More ships of course, more sailors to man them. The new ironclads would prove to be invincible and would strike terror in the Americans’ hearts. Now the admiral nodded slowly in ponderous acknowledgement of his responsibility, his large and fleshy nose bobbing up and down.

“It will be my pleasure to inform Her Majesty as to all matters naval, to reassure her that the senior service is in good and able hands.”

“Good then, we are of a mind. To the palace.”

When they were ushered into the Presence at Buckingham Palace the Queen was sitting for a portrait, her ladies in waiting watching and commenting quietly among themselves. When they entered Victoria dismissed the painter, who exited quickly, walking backwards and bowing as he went.

“This is being painted for our dearest Vicky, who is so lonely in the Prussian Court,” she explained, speaking more to herself than to the others present. “Little Willie is such a sickly baby, with that bad arm he is a constant trial. She will be so happy to receive this.” Her slight trace of a smile vanished when she looked up at the three men. To be replaced by petulant, pursed lips.

“We are not pleased at this interruption.”

“Would it had been otherwise, ma’am,” Lord Palmerston said, executing the faintest of bows. “Exigencies of war.”

“When we spoke last you assured me that all was well.”

“And so it is. When the troops are mustered and ready in Mexico, then the fleet will sail. In the meantime the enemy has been bold enough to attack our merchant fleet, peacefully at anchor in port, in Mexico, causing considerable damage…”

“Merchant ships damaged? Where was our navy?”

“A cogent question, ma’am. As always your incisive mind cuts to the heart of the matter. We have only a few ships of the line in the Pacific, mainly because the enemy has none at all there. They do now – so we must make careful provision that the situation does not worsen.”

“What are you saying? This is all most confusing.”

Palmerston gave a quick nod and the admiral stepped forward.

“If I might explain, ma’am. Circumstances that have now been forced upon us mean that we must now make provision for a much larger Pacific fleet. We have not only received information that the Americans are increasing the expansion of their navy, but are preparing coaling stations to enable them to attack us in the Pacific Ocean.”

“You are confusing Us. Coaling ships indeed – what does this mean?”

“It means, ma’am, that the Americans have widened the field of battle. Capital ships must be dispatched at once to counter this attack,” Gladstone said, reluctantly stepping forward. “We must enlarge our fleet to meet this challenge. And more ships mean more money. Which must be raised at once. There are certain tax proposals that I must set before you…”

“Again!” she screeched, her face suddenly mottled and red. “I hear nothing except this constant demand for more and more money. Where will it end?”

“When the enemy is defeated,” Palmerston said. “The people are behind you in this, Majesty, they will follow where you lead, sacrifice where you say. With victory will come reparations – when the riches of America flow once again into our coffers.”

But Victoria was not listening, lolling back in her chair with exhaustion. Her ladies in waiting rushed to her side; the delegation backed silently out. The new taxes would go through.

In Mexico the battle was not going very well. General Ulysses S. Grant stood before his tent as the regiments slowly moved by at first light. He chewed on his cigar, only half aware that it had gone out. They were good men, veterans, who would do what was required of them. Even here in this foul jungle. He was already losing men to the fever, and knew that there would be more. This was no place to fight a war – or even a holding action like this one. Before he had left Washington, Sherman had taken him aside and explained how important the Mexican front was. The pressure of his attacks, combined with Pacific naval action, would concentrate the British attention on this theater of war. Grant still hated what he was doing. Feeding good soldiers into the meat grinder of a war he was incapable of winning. He spat the sodden cigar out, lit a fresh one and went to join his staff.

Soon after dawn the three American regiments had gathered close to the jungle’s edge, concealed by the lush growth. The guns had been moved up a day earlier, man-hauled into position by the sweating, exhausted soldiers. The clear sound of a bugle sounded for them to fire. It was a heavy bombardment, with the guns standing almost wheel to wheel. Shell after explosive shell burst on the defensive line above. Clouds of smoke billowed up from the flaming explosions. When the firing was at its heaviest the soldiers had started their attack. They marched across the stretch of dead vegetation – then began to clamber up the steep slope of the defenses. As soon as they did the barrage lessened, then died away as the attackers climbed higher.

General Ulysses S. Grant stood to the front, waving them to the attack with his sword. They cheered as they passed him, but soon quieted as they scrambled up the steep slope in the endless heat. Men were beginning to fall now as the defenders, despite the barrage of cannon shells, crawled forward to fire down at the attacking troops. When the first ranks were halfway to the top of the ridge the American cannonfire ceased for fear of hitting their own troops. Now the British firing increased, mixed with the boom of cannon from their dug-in positions.

Men were dropping on all sides – and still on they came. Despite the withering fire the broken ranks of the 23rd Mississippi reached the summit with a cheer. It was bayonets now – or bayonets against kukris, for this portion of the line was held by Gurkha troops. Small, fierce fighting men from Nepal, they neither asked for mercy – nor extended it. As more American troops joined the attackers the Gurkhas were forced back. When the third wave climbed the outer defenses of the lines, General Grant was with them. He, and his adjutant, had to roll aside the corpses of the first attackers to reach the summit.

“Damnation,” Grant said as he chomped down on his dead cigar. “Ain’t no place to go from here.”

That was true enough. Below him was the road, the dirt track through the jungle over the possession of which the two armies now clashed. Although the slope below him was clear of any living enemy – the same could not be said of the far side of the road. Dug-in defenders and cannon were raking his position. While down the road, in both directions, galloping horses were approaching, hauling cannon forward. Nor could the Americans move left or right down the defensive line because of the well dug-in positions that were there, adding their shells to the withering fire on the attackers who barely held the ridge.

Grant spat the cigar out, stood up despite the increasing hail of lead.

“We are not going to hold here very long. As soon as those guns get into position they can wipe us out at first go. If we stay here it is as good as suicide. And there ain’t any other place to go – except back.” He turned to his adjutant. “Get the Mississippians out first, they got bloodied well enough for one day. When they are clear sound retreat and get the rest of these men back down this hill just as fast as they can run.”

He did not leave until the first men had reached the safety of the jungle. Only then, reluctantly, did he join in the fighting retreat.

Well, they had had their noses bloodied this day. But he had looked into the enemy’s works and faced their troops. All men of color – but real warriors. And he had broken the British line once – and what they had done once they could do again if they had to. Make a real breach next time, then widen it and cut the road in two. He would talk to the engineers. Perhaps there was the possibility of tunneling under the defenses to plant a mine. Put in a big enough one and it might be able to sever the road and its defenses in one go. If he could do that, and hold it, he could very well put the coming invasion of enemy troops down this road in jeopardy.

But it was going to be a mighty hard thing to do.

THE MEXICAN FILE

Gustavus Fox was seated in the anteroom of Room 313, a half an hour before noon, the time when the meeting was due to begin. He had already checked off two names on his list of those who would be present. General Sherman and General Lee, who had requested that this meeting take place. They had been waiting for him when he arrived at eight that morning to unlock the door. Lee had been carrying a battered leather saddlebag which he never let go of. Fox did not ask about its contents – he would know soon enough. But his curiosity was so great that he could not keep his eyes off it. Lee had seen this and smiled.

“Soon, Gus, soon. You must be patient.”

He did try to be patient, but still he could not keep his eyes off the clock. At a quarter to twelve there was a quick rap on the door and he crossed over to unlock it. The two guards outside were standing at attention; he straightened up himself when the tall and lanky form of the President walked in. He waited until the door had been relocked before Lincoln spoke.

“We finally get to look inside – as the boy said when he opened his Christmas present.”

“I certainly hope so, sir. Generals Sherman and Lee have been here all morning. And General Lee was carrying a mighty full saddlebag.”

“Well he will have all of our attention I assure you. How is our other invasion going?”

“Very well indeed. All of our coaling provisions are in place. And I have reports from agents in England that not only have our preparations been observed, but plans for counter-measures are already in progress. Whoever is spying for the enemy here was very quick off the mark. Whatever agent they have in this country is very efficient. I would dearly love to find out who he is.”

“But not at the present time.”

“Indeed not! Whoever he – or she – is, why they are working for me right now.”

“And the British are paying him. A remarkable arrangement. Ah, there you are Seward,” he said as the Secretary of State entered.

The members of the small circle arrived one by one. Welles and Stanton arrived together, completing their number.

“Shall we go in?” Lincoln asked, pointing to the locked inner door.

“In a moment, gentlemen,” he said as there was a rap on the outer door. Lincoln’s eyebrows rose in unspoken query.

“Our numbers have increased by one since last we met,” Fox said as he unlocked the door.

An erect, gray-haired man in naval uniform came in. Fox locked the door, turned and spoke. “Gentlemen, this is Admiral Farragut who has already been aiding us. Shall we go inside? If you please, gentleman,” Fox said as he unlocked the door to the inner room. Went in after them and locked it behind him.

Sherman and Lee were sitting at the conference table, the saddlebag on the table between them. When they were all seated Lee opened the bag and took out a thick sheaf of papers that he passed to Sherman. Who touched them lightly with his fingertips, looked at the others present with a cold and distant look in his transparent eyes.

“I see you all have met Admiral Farragut, who has been of singularly great assistance to us in our planning,” Sherman said. “His naval wisdom was vital in drawing up what we have been referring to as the Mexican File. So if, by any chance, the name of the operation is overheard, the assumption will be that it refers to our Pacific Ocean operations. The Mexican File comes in two parts.” He separated out the top sheaf held by a red ribbon.

“These orders conform to the proposed attacks that the British now know about. We wish to confer with the Secretary of the Navy after this meeting, in order to transform general fleet movements into specific sailing orders. This operation will begin when a group of warcraft, containing four of our new ironclads, proceeds south as far as Recife in Brazil. They will coal there, then leave port and sail in a southerly direction. The ship’s officers have orders to refuel again at the port of Rawson in Argentina. The Argentines have been informed of their arrival. They will also have orders commanding them to proceed to Salina Cruz, Mexico, to engage any British men-of-war that may be stationed there.” He opened the file and smoothed the pages out.

“The next movements will occur two weeks after the ironclads leave. At this time the fleet of troop-carrying transports will be assembled. They will leave various east-coast ports, to rendezvous off Jacksonville, Florida. They will be joined there by more ironclads. At noon on the first day of September they will all form up and sail south.

“That same night, at nine in the evening, they will all open their sealed orders – that will put them on a new course.” He nodded at Fox who stood and went to the map cabinet, unlocked and opened it. Fixed to the open door was a chart of the Atlantic Ocean. Facing it in the cabinet was the map of Ireland. Sherman walked across the room, every eye on him, and touched a spot in the Atlantic west of the Iberian Peninsula.

“This is their destination. I doubt if you can see this group of islands from where you are sitting, but I assure you that they are there. They are the Azores. On the most northern of these islands, Graciosa, there is a coaling port at Santa Cruz de Graciosa. Ships from Portugal and Spain refuel there on the way to South America. This will be the new rendezvous of the invasion fleet. Arriving on the same day will be the ironclads that the world believes were headed for Cape Horn. Once out of sight of land their sealed orders will also have directed them to this same coaling port. Admiral Farragut, will you elucidate.” He sat down as the admiral crossed to the map and ran his finger around the Azores.

“Sailing times have been carefully calculated, allowance made for irregularities such as storm or accidents. Once both fleets are out of sight of land, their new orders will take them to this secret rendezvous in the Azores. There should be no suspicion that their courses have been changed, because they will be expected to be at sea and out of sight of land for this carefully calculated period. After arriving at the island of Graciosa they will have twenty-four hours to refuel – then set sail. Before I go into the final period – are there any questions?”

Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy, looked apprehensive. “So many ships at sea, there will surely be chance encounters with other ships.”

“There undoubtedly will be, sir,” Farragut said firmly. “But we are at war, we are about to be invaded, and our counter-measure to this planned invasion will be positive in our defense. British ships will be captured and made prizes. Ships of other nations will be boarded and will accompany our ships to Graciosa. There they will remain for three days after the fleet departs. Only then will they be permitted to leave. Even if one of them should go directly to Spain, where the nearest telegraph is located, it will still be too late. Our invasion will already have begun.”

Welles still wasn’t satisfied. “So many ships involved, so many changes of plans, refueling – much can go wrong…”

“If it does – it will not be through fault of planning. Every distance has been measured, every ton of coal accounted for. There may be minor mishaps, there always are with a maneuver this size, but that cannot be helped. But this will not alter or interfere with the overall plan.”

“Which is what?” The president asked quietly.

“I defer to General Sherman,” the admiral said and regained his seat.

Sherman stood beside the map of Ireland, pointed to it.

“This is where we will land.” He waited until the gasps and murmurs of excitement had died away before he continued. “This is where we will defeat the enemy forces. This is the island that we will occupy. This is where the theatre of war will be – and where the threatened invasion of our country will end. Britain dare not commit so many troops to foreign adventures when the enemy is at the gate, threatening the very heart of her Empire.

“And now I will tell you how we will do it.”

Allister Paisley was a curious man – and a very suspicious one as well. He was an opportunist, so that most of his petty crimes were committed on the spur of the moment. Something of value left unguarded, a door invitingly open. He was also very suspicious and thought every man his enemy. Which was probably right. After he had sent his report on the American activities to England, by way of Belgium, he still wanted additional information. He was paid for what he delivered, and the more he delivered the more money he had to spend. Not so much on alcohol these days, but on the far more satisfactory opium. He sat now in the grubby rented room in Alexandria, Virginia, heating the black globule on the pierced metal opening of his pipe. When it was bubbling nicely he inhaled deeply through the tall mouthpiece. And smiled. Something that few people living had seen him do. As a child he may have smiled: none alive would remember that. Now the sweet smoke burned away all cares. As long as he had the money he could smile; it was wonderful, wonderful.

Not so wonderful next morning in the damp chill of dawn. Rain was blowing in through the half-open window. He stepped in a pool of water when he got up and slammed it shut. All the smoke from his night’s pleasure was now dispersed. Through the sheets of rain he could just make out the buildings of Washington City just across the river. He shivered and pulled on his shirt, then drank some whisky to free him from the chill.

The rain stopped by noon and a watery sun occasionally appeared behind the clouds. At five in the afternoon Paisley had crossed the river into the capital and was now leaning against a wall on Pennsylvania Avenue, watching the clerks emerge from the War Department. He inhaled deeply on his cheap cheroot and looked for one particular face in the crowd. Yes, there he was. A gray man in gray clothing, scuttling along like a rodent. Allister stepped forward and fell in beside him, walked a few paces before the other man noticed him – and twitched, startled.

“Hello Georgy,” Paisley said.

“Mr. McLeod – I didn’t see you.” Few men, if any, knew Paisley’s real name.

“How’s the work going, Georgy?”

“You know, they keep us busy.” Giorgio Vessella, one generation away from Italy, was not a happy man. His parents, illiterate peasants from the Mezzogiorno, had been proud of him. An educated man with a position in the government. But he knew how little he earned, how insecure his position was. Only in wartime would they have even considered hiring a foreigner, as he would always be to the authorities’ Anglo-Saxon eyes; his tenure was always suspect. Now, and not for the first time, did he regret that he had ever set eyes on the Scotsman.

“Let’s go in here. Have a drink.”

“I told you, Mr. McLeod, I don’t drink. Just wine sometimes.”

“All guineas drink,” Paisley said with instant racial intolerance. “If you don’t want it I’ll drink it for you.”

It was a dismal little alehouse, the only kind Paisley frequented, and they sat at a table in the corner away from the few other clientele. Paisley drank a good measure of the raw spirit and wiped his mouth with the back of his hand. His other hand tapped a silver dollar lightly on the stained table. Giorgio tried not to see it, but his eyes kept straying back to it.

“They keep you busy?”

“Just like always.”

“I waited a couple of times. You never came out.”

“We’ve been working late for a number of weeks now. The Navy Department ran short of clerks to copy orders. They sent over a lot of ship movements and we have been copying for them.”

“I know about those,” Paisley yawned widely. “Ships to Mexico.”

“That’s it. A whole lot of them.”

“Old news. I only pay for new news. You got any of that?”

“No, sir. I just copy what they tell me to. The same old thing. It’s just Mr. Anderton and Mr. Foyle, they get to do the different stuff in the locked room.”

“What different stuff?” He said it offhandedly, almost bored, finished his drink. It sounded like there was something of some importance here.

“More naval orders, I heard them talking. They were excited. Then they looked at me and laughed and didn’t say anything else.”

All of the military clerks were trusted, Paisley thought. But some were trusted more than the others. Clerks who worked in a locked room inside a locked room. And why had they laughed? A secret within a secret? Superiority? They knew something that the other clerks didn’t.