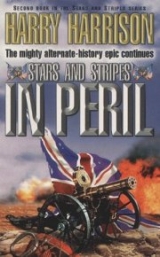

Текст книги "Stars and Stripes In Peril"

Автор книги: Harry Harrison

Жанр:

Альтернативная история

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

“The gas seal would be complete. But it would be the devil’s own job – and a slow one at that – to screw a long bolt in and out between each shot.”

“Of course. So let me show you…”

Parrott went to the rear of the gun and reached up to strain at a long lever. He could barely reach it, nor was he able to pull it down. The taller Swede who, despite his advanced age, was immensely strong, reached past the small gunsmith and pulled the bar down with a mighty heave. The breech-block rotated – then swung aside on a large pinned hinge. Ericsson ran his fingers over the threads on block and barrel.

“It is an interrupted screw,” Parrott said proudly. “The theory is a simple one – but getting the machining right was very difficult. As you can see, after the breach and the breechblock have been threaded, channels are cut in each of them. The block then slides forward into place. And with a twist it locks. A perfect gas seal has been accomplished by the threading. After firing the process is reversed.”

“You are indeed a genius,” Ericsson said, running his fingers over the thick iron screw threads. Possibly the only time in his life that he had praised another man.

“If you will show me the ship on which it will be mounted…”

“Difficult to do,” Ericsson said, smiling as he tapped his head. “Most of it is inside here. But I can show you the drawings I have made. If you will step inside my office.”

Ericsson had not stinted himself with the government’s money when he had designed a workplace for himself. He had labored for too many years in the past in drafty drawing rooms, sometimes only feebly lit by sooty lanterns. Now large windows – as well as a skylight – illuminated his handsome mahogany-framed drafting table. Shelves beside it contained models of the various ships he had designed, other inventions as well. The drawing of Virginia was spread across the table. He tapped it proudly with his finger.

“There will be a turret here on the forelock, another aft. Each will mount two of your guns.”

Parrott listened intently as the Swedish engineer proudly pointed out the details that would be incorporated into his latest design. But his eyes kept wandering to a chunky metal device that stood on the floor. It had pipes sticking out from it and what appeared to be a rotating shaft projecting from one side. At last he could control his curiosity no longer. He tried to interrupt, but Ericsson was in full spate.

“These turrets will be far smaller than those I have built before because there will be no need to pull the gun back into the turret after firing to reload through the muzzle. Being smaller the turret will be lighter, and that much easier to rotate. And without the need of pulling the guns in and out after each shot the rate of fire will be faster.”

He laughed as he clapped the small man on the back, sent him staggering. “There will be two turrets, four guns. And I shall design the fastest armored ship in the world to carry these guns into battle. No ship now afloat will stand against her!”

He stepped back, smiling down at his design, and Parrott finally had a chance to speak. “Excellent, excellent indeed. When I return I shall begin work on the other three guns at once. But pardon me, if you don’t mind – could you tell me what this machine is?”

He tapped the black metal surface of the machine and Ericsson turned his way.

“That is a prototype, still under development.” He pointed back at the drawings of his iron ship. “This new ship will be big – and with size comes problems. Here look at this.”

He picked up a half-model of Monitor and pointed out the steam boiler. “A single source of steam here, that is more than enough in a ship this size. The turret you will notice is almost directly above the boiler. So it was simple enough to run a steam line to it to power the small steam engine that rotates the turret. But here, look at the drawing of Virginia. Her engine is on the lowest deck. While the turrets are far above, fore and aft. This means that I will need insulated steam lines going right through the ship. Even when they are insulated they get very hot. And there is the danger of ruptures, natural or caused by enemy fire. Live steam is not a nice thing to be near. Should I have a separate boiler under each turret? Not very practical. I have considered this matter deeply, and in the end I have decided to do it this way.”

“You have considered electric motors?”

“I have. But none are large enough to move my turrets. And the generators are large, clumsy and inefficient. So I am considering a mechanical answer.” He looked over at the engineer. “You have heard of the Carnot cycle?”

“Of course. It is the application of the second law of thermodynamics.”

“It is indeed. The ideal cycle of four reversible changes in the physical condition of a substance. A steam engine works in a Carnot cycle, though since the source of energy is external it is not a perfect cycle. In my Carnot engine I am attempting to combine the complete cycle in a single unit. I first used coal dust as a fuel, fed into the cylinder fast enough so that isothermal expansion would take place when it burned.”

“And the results?” Parrott asked enthusiastically.

“Alas, dubious at best. It was hard to keep the cylinder temperature high enough to assure combustion. Then there is the nature of the fuel itself. Unless it is ground exceedingly fine, a weary and expensive process at best, it tended to lump and clog the feed tube. To get around that problem I am now working with coal oil and other combustible liquids with improved results.”

“How wonderful! You will have a self-contained engine under each turret then. You will keep me informed of your progress?”

“Of course.”

Parrott thought of the patent of the land battery that had been hanging on his office wall for many years. A most practical idea. Lacking only an engine sufficiently small to move it.

Was Ericsson’s machine going to fulfill that role?

Gustavus Fox was signing papers at his desk when the two Irish officers came in. He waved them to the waiting chairs, then finished his task and put his pen aside.

“General Meagher – do I have your permission to ask Lieutenant Riley a few questions?”

“Ask away, your honor.”

“Thank you. Lieutenant, I noticed that scar on your right cheek.”

“Sir?” Riley looked concerned, started to touch the scar, then dropped his hand.

“Could that scar once have been – the letter ‘D’?”

Riley’s fair skin turned bright red and he stammered an answer. “It was, sir, but…”

“You were a San Patricio?”

Riley nodded slowly, slumped miserably in his chair.

“Mr. Fox,” Meagher said. “Could you tell me just what this is all about?”

“I will. It happened some years ago when this country went to war against Mexico. Forty years ago. There were Irish soldiers in the American army even then. Good, loyal soldiers. Except for those who deserted and joined the Mexican army to fight for the Mexican cause.”

“You never!” Meagher cried out, fists clenched as he rose to his feet.

“I didn’t, General, please. Let me explain…”

“You will – and fast, boyo!”

“It was the Company of Saint Patrick, the San Patricios they called us in Spanish. Most of the company were deserters from the American army. But I wasn’t, sir! I had just come from Ireland and I was in Texas on a mule train. I was never in the American army. I joined the Mexicans for the money and everything. Then when we were captured General Winfield Scott wanted to hang the lot of us. Some were hung, others got off with being lashed and branded with the ‘D’ for deserter. I swore I had never been in the army, and they could find no record of me whatsoever. They believed me then so I didn’t get the fifty lashes. But they said I still fought against this country so I was branded and let go. I rubbed the brand, broke the scab and all, so you couldn’t see the letter.” Riley raised his head and straightened in his chair.

“That’s the whole of it, General Meagher. I swear on the Holy Bible. I was a lad from Kerry, some months off the boat, and I made a mistake. Not a day has gone by that I didn’t regret what I had done. I joined this army and I have fought for this country. And that is all I ever want to do.”

Meagher wrinkled his brow in thought; Fox spoke.

“What do you think, General? Do you believe him? I will leave the decision to you.”

Meagher nodded. Lieutenant Riley sat erect, his skin pale as death. Seconds passed before Meagher spoke.

“I believe him, Mr. Fox. He is a good soldier with a good record and I think he has more than paid for what he did so long ago. I’ll have him – if you agree.”

“Of course. I think the lieutenant will be a better soldier now that the past is known. Perhaps he can finally put the past behind him.”

The hackney cab came along Whitehall and turned into Downing Street, stopping in front of Number 10. The cab driver climbed down from his seat and opened the door. The military officer who emerged had to be helped to step down. His face was thin and cadaverous, his skin quite yellow, sure signs of the fever. Since he was being sent home on sick leave he had been trusted with the latest reports. Although the grueling trip on muleback to Vera Cruz had almost finished him off, he was recovering now. He shivered in the pale spring sunshine, tucked the bundle of papers under his arm and hurried inside as soon as the door was opened.

“This is Major Chalmers,” Lord Palmerston said when the officer was ushered into the Cabinet Room. “A chair for him, if you please. Ahh, yes, the reports, I’ll take them if you please. Gentlemen, despite his obvious ill health the major has been kind enough to appear before us today to personally report on the progress of our road. Is that not right, sir?”

“It is indeed. I must, in all truth, say it was rather a slow start, since we only had a few Indian regiments in the beginning. I myself did the first survey. The worst part of the construction was the swamps near the coast. In the end we had to raise the road on a dyke, after the fashion of the Dutch, with culverts beneath it so the tidal flats could drain back into the sea…”

Chalmers coughed damply and took a kerchief from his sleeve to wipe his face. Lord Russell, seeing his obvious distress, poured a glass of water and took it to him. The major smile weakly and nodded his thanks, then went on.

“After the swamps we were back in jungle again. In addition, there is a backbone of low hills running the length of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec which must be crossed. No real difficulties there, though a few bridges will have to be built. Plenty of trees so that won’t be a problem. Then, once past the hills, we will be on the Atlantic coastal plain and the grading will be that much easier.”

“You have a completion schedule, I do believe,” Lord Palmerston said.

“We do – and I believe that we will better it. More and more regiments are arriving and they go right to work. We have enough men now so that we can rotate them for the most onerous duty. I can firmly promise you, gentlemen, that when you need the road it will be there.”

“Bravo!” Lord Russell said. “That is the true British spirit. We all bid you a speedy recovery, and sincerely hope that you will enjoy your leave here in London.”

A DANGEROUS JOURNEY

Don Ambrosio O’Higgins left the paddle wheel coaster after dark. A small carpetbag was passed down to him, then a long bundle wrapped in oiled canvas. He seized up the bag, put the bundle over his shoulder and started forward – then stepped back into the shadows. A French patrol had appeared on the waterfront, lighting their way with a lantern. They proceeded carefully, muskets ready, looking in all directions as they came forward. They knew full well that every hand was against them in this country of Mexico. O’Higgins crouched down behind some large hogsheads, staying there until the patrol had passed by. Only then did he make his way quickly across the open docks and into the safety of the now familiar streets of Vera Cruz. There were many other French patrols in the city, but they never penetrated these dark and dangerous back alleys. Too many patrols had been ambushed, too many soldiers had never returned. Their weapons lost, now used to fight the invaders. O’Higgins kept careful watch around him, for not only the French were unsafe in these dismal streets. He emitted a low sigh of relief when he finally reached the merchant’s shop. It was locked and silent. O’Higgins felt his way carefully to the rear of the building where he tapped lightly on the back door. Then louder still until a voice called out querulously from inside.

“Go away – we are closed.”

“Such a cold greeting for an old friend, Pablocito. I am wounded to the core.”

“Don Ambrosio! Can that be you?”

The bolt rattled as it was drawn back. A single candle lit the room; Pablo resealed the door behind him, and then went to fetch a bottle of the special mezcal from the town of Tequila. They toasted and drank.

“Any news of interest from Salina Cruz since I went away?” O’Higgins asked.

“Just more of the same. Reports filter in that the English are still bringing in their troops. The road advances slowly – but it advances. When these invaders are thrown from our country – God willing! – we will at least have the road that they will have to leave behind. Everything else they steal from our country. But a road – no!” Then Pablo touched the canvas-wrapped package with his toe.

“Another mission?” he asked. O’Higgins nodded.

“Like you, I fight for the freedom of Mexico. Also like you I do not speak of what I do.” Pablo nodded understandingly and drained his glass.

“Before the French came Mexicans were always ready to fight Mexicans. When the French are driven out they will undoubtedly fight each other again. There are those now out of power who are just biding their time, waiting for the French to leave.”

“I sorrowfully admit that I know little of Mexico’s turbulent past.”

“That is a good word for it. Before the Conquistadores came the various Indian tribes warred with one another. Then they warred with the Spanish. When the tribes were defeated they were enslaved. I must tell you that I go to mass and am most religious. But Mexico will not be free until the power of the church is broken.”

“They are that strong?”

“They are. I believe that there are over six thousand priests and over eight thousand members of religious orders. All of them above the law because of the fuero, their own courts of justice. If that is the word. They own enormous properties where the friars live in luxury while the poor starve. The bishops of Puebla, Valladolid and Guadalajara are millionaires.”

“Is there no way out?”

“It happens. Slowly. We had electoral reform in 1814 where all could vote, an elected congress, it was all lovely. Then the French came. But enough of the past. We must fight now. At least we are both on the side of the Liberals and of the government of Benito Juarez. I have heard that he fled north when the French advanced.”

O’Higgins nodded. “I understand he is in Texas now, waiting only to return.”

“May that day come soon. Shall I send for Miguel?”

“In the morning. And the donkeys?”

“Getting fat in his fields. I have seen him there when I was passing by. I have even ridden your Rocinante a few times. She is fit and willing.”

“I thank you. The donkeys will work that fat off fast enough, never fear.”

They sat and talked, until the candle was guttering and the bottle empty. Pablo stood and yawned widely. “Do you wish a bed in the house? I’ll have one made up.”

“Thank you – but I must say no. My blanket in the storeroom will suffice. The fewer people that know I am here the better.”

Miguel appeared at dawn. They packed their meager supplies during the morning, then had a midday meal of beans and tortillas with Pablo. They left soon after noon. The French had readily adapted to the Mexican siesta, so the streets were empty during the heat of the day. O’Higgins led the way out of the city, to the trails that meandered into the jungle to the east.

“Do we return to Salina Cruz?” Miguel asked.

“Not this time. We follow the trail only as far as San Lucas Ojitlán. Then turn south, into the Oaxaca Mountains. Do you know the trails?”

Miguel nodded, then shook his head unhappily. “I know them, yes, but they are not safe. Not unless you are a friend of Porfirio Diáz. He and his followers are the law there in the mountains.”

“I have never met the good general – but I am sure that he will be very happy to see me. How do we find him?”

“That is not a problem. He will find us,” Miguel said, his voice laden with doom.

It was hot under the afternoon sun but they kept moving, stopping only to rest and water their beasts of burden. This time they encountered no French troops. By mid-afternoon clouds had moved in from the sea, cooling the air. A light rain fell which they ignored.

The flat coastal plain of Tehuantepec ended abruptly at the foothills of the Oaxaca Mountains. As they went higher they came to fewer and fewer villages, since there were very few places among the crags that were fit for farming. Fifty years of revolution after revolution had left their mark as well. They passed by one nameless village, now only a burnt and blackened shell. The trail went on, slowly winding uphill between the trees. It was cooler at this altitude, as the lowland shrubbery gave way to giant pine trees. The hoofbeats of their animals were muffled by the carpet of pine needles, the only sound the wind rustling in the branches above them. Further on they emerged into a clearing and found a mounted man barring their way.

O’Higgins pulled his horse up. He thought of reaching for his gun, then quickly changed his mind. This was no chance encounter. They must have been watched, followed, cut off. The mounted man did not reach for the rifle slung across his back, but movement in the foliage to both sides of the path proved that he was not alone. He had the emotionless face of an Indian; his black eyes stared coldly at O’Higgins from under the brim of his large sombrero. Miguel had pulled up the donkeys as soon as he had seen the stranger. O’Higgins dismounted slowly, carefully keeping his hands away from his weapons. He handed the reins to Miguel and walked slowly towards the horseman.

“That’s far enough,” the man said. “We do not see many strangers in these mountains. What do you want?”

“My name is Ambrosio O’Higgins and I am here on a mission. I want to see Porfirio Diáz.”

“What is your business with him?” As he spoke the rider flipped his hand. A number of men – all carrying rifles – emerged from the undergrowth on both sides of the trail. O’Higgins paid them no attention and spoke directly to the rider.

“My business is with Diáz alone and I assure you that it is of great importance. All I can tell you is that he will consider it most critical when he understands why I have sought him out. He will surely want to talk with me when he understands why I have come to his mountains.”

“Why should I believe you? Why shouldn’t I shoot you on the spot?”

Miguel began to shake so badly that he had to clutch his saddle so he wouldn’t fall off. However O’Higgins showed no emotion – and his stare was as just as cold as the other man’s.

“If you are a bandit then I have no way of stopping you. But if you are a warrior and a Juarista, why then you will take me to your leader. I fight for a free Mexico – as do you.”

“Where do you come from?”

“We left Vera Cruz today.”

“And before that?”

“I will be happy to tell that to Porfirio Diáz.”

“Why should I believe anything that you say?”

“Because you must believe – since you dare not make any other decision. This is a chance that you have to take. And consider – for what other reason would I be traveling in these hills? It would be suicidal if I did not have legitimate reason to talk with Diáz.”

The horseman thought about that – and made a decision. He waved his hand again and his followers lowered their guns. Miguel let out his breath in a relieved sigh and crossed himself with trembling fingers. O’Higgins remounted and rode forward to join the other man.

“What of the war?” the guerrillero asked.

“It goes very badly. The French are victorious everywhere. Juarez has been defeated but has managed to escape to Texas. The French hold all of the cities. Monterrey was the last to fall. But Mexico itself is not defeated – never will be. Fighters like yourselves hold the mountains where the French dare not follow them. Regules is in Michoacán with armed followers, Alvarez the same in Guerrero. These are places where the French dare not go. And there are others as well.”

The trail narrowed and the horseman pulled ahead. They rode on slowly so the men on foot could keep up with them. The trail meandered up through the trees, occasionally forking, at other times vanishing altogether. They crossed broken scree, then entered another pine forest: the pine needles underfoot smelling sweetly as the horses’ hooves sunk silently into their surface. Then, through the smell of pine, there was a whiff of burning wood. Soon after this they came out into a clearing scattered with brushwood huts. Sitting on a log outside the largest shelter was a young man in uniform, a general’s stars on his shoulders.

So young, O’Higgins thought, as he swung to the ground. Thirty-three years old – and fighting for most of those years for Mexican freedom. Three times he had been captured, three times he had escaped. This young lawyer from Oaxaca had ridden a hard trail, had come a long way.

“Don Ambrosio O’Higgins at your service, General.” Diáz nodded coldly and looked the newcomer up and down.

“That is not a very Mexican name.”

“That is because I am not a Mexican. I am from Chile. My grandfather came from Ireland.”

“I have heard of your grandfather. He was a great fighter for freedom from Spain. And was an even greater politician, as was your father. Now – what does an O’Higgins want of me that is so important that he risks his life in these mountains?”

“I want to help you. And I hope that you will aid me in return.”

“And how will you be able help me? Do you wish to join my guerrilleros?”

“The help I bring you is worth far more than just another man to fight at your side. I want to help you by bringing you many of these. From America.” He began to unwrap the canvas bundle. “I have seen the weapons that your men carry. Muzzle-loading smooth-bore muskets.”

“They kill Frenchmen,” Diáz said, coldly.

“Your men will kill that much the better when they have many of these.”

He pulled the gun out of the canvas wrapping and held it up. “This is a Spencer rifle. It loads from the breech like this.”

He took out a metal tube and pushed it into an opening in the wooden stock, then worked the cocking lever. “It is now loaded. It contains twenty bullets in that tube. They can be fired just as fast as they can be levered into the firing chamber and the trigger pulled.” He passed the rifle over to Diáz who turned it over and over in his hands.

“I have heard of these. Is this how you load it?”

He pulled the lever down and back and the ejected cartridge fell to the ground.

“It is. Then, after firing, you do the same thing again. The empty cartridge will be ejected and a new one loaded.”

Diáz looked around, pointed at a dead tree ten yards away and waved his men aside. He raised the rifle and pulled the trigger; splinters flew from the tree. He loaded and fired loaded and fired until the magazine was empty. There was a splintered circle on the tree; smoke hung in a low cloud. The silence was broken as the guerrillerros shouted loud approval. Diáz looked down at the gun and smiled for the first time.

“It is a fine weapon. But I cannot win battles with this single gun.”

“There is a ship now loading in the United States that will bring a thousand more of these – and ammunition. It will be sailing for Mexico very soon.” He took a heavy leather bag from the roll and passed it over as well. “There are silver dollars here which you can use for food and supplies. There will be more coming on the ship.”

Diáz leaned the rifle carefully against the log and hefted the money bag.

“The United States is most generous, Don Ambrosio. But this is a cruel and savage world and only saints are generous without expecting some kind of reward in return. Has your country suddenly become a nation of saints? Or is there something that they may want from me in return for all this largesse? It was not so long ago that I walked out of these mountains to join the others in the battle for my country – against your Gringo invaders from the north. That war is hard to forget. Many Mexicans died before the American guns.”

“Those days are long over. As is the war between the states. There is peace in America now between North and South, just as there is peace between the American government and your Juaristas. Guns and ammunition, like these, are crossing the border in greater numbers. America is waging a diplomatic war against Maximilian and the French. It will be a fighting war if the French do not acquiesce to their demands. Even as we speak attacks by Juaristas in the north are being launched against the French, and the Austrian and Belgian troops they command.”

“And your Americans wish me to do the same? To march against Mexico City?”

“No. Their wish is that you go south. Have you heard of the troop landings there?”

“Just some mixed reports. Strange soldiers in strange uniforms. Something about building a road. It is hard to understand why they should be doing this here. People I have talked to think that they must be mad.”

“The soldiers are British. And far from being mad they have a carefully worked out plan. Let me show you, if I may?”

Diáz waved him over. He took a map from his saddle pouch and unrolled it. He sat beside Diáz on the log and pointed at the south of Mexico.

“The landings were made here on the Pacific shore at the small fishing village of Salina Cruz. The soldiers are from many countries in the East, but mainly from India. Their commanders are British, and what they mean to do is to build a road across the isthmus here, to Vera Cruz on the Atlantic.”

“Why?”

“Because these troops are from many places in the British Empire. From China and India. The North Americans, though they do not wish it, are still at war with the British. They believe that when the road is complete these troops will be used to invade the United States.”

“Now it is all becoming very clear,” Diáz said, his voice suddenly cold. “Your Americans wish me to pull their hot chestnuts from the fire. But I am a patriot – not a mercenary.”

“I think that it would be more correct to say that my enemy’s enemy is my friend. These British troops are also allies of the French. They must be driven from Mexican soil. As proof of what I say I have something else for you.” He drew the envelope from inside his jacket and passed it over.

“This is addressed to you. From Benito Juarez.”

Diáz held the letter in both hands and stared at it thoughtfully. Juarez, the President of Mexico. The man and the country for which he had fought these many long years. He opened it and read. Slowly and carefully. When he had finished he looked over at O’Higgins.

“Do know what he says here?”

“No. All I know is that I was told only to give it to you after I had told you about the guns and the British.”

“He writes that he and the Americans have signed a treaty. He says that he is returning from Texas and is bringing with him many rifles and ammunition as well. He also brings American soldiers with cannon. They will join with the guerrilleros in the north. Attack through Monterrey and then move on to Mexico City. The invaders shall be driven back into the sea. He asks that I, and other guerrilleros here in the south, fight to stop the British from building this road. He writes that this is the best way that I can fight for Mexico.”

“Do you agree?”

Diáz hesitated, turning the letter over and over in his hand. Then gave a very expressive shrug – and smiled.

“Well – why not? They are invaders after all. And mine enemy’s enemy as you say. So I shall do what all good friends must do for one another. Fight. But first there is the matter of the weapons. What will be done about that?”

O’Higgins took a much-folded map from his pocket and spread it on his knee and touched the shore on the Gulf of Mexico. “An American steamer is loading the rifles and ammunition here in New Orleans. In one week’s time it will arrive here, in this little fishing village, Saltabarranca. We must be there to meet it.”

Diáz looked at the map and scowled. “I do not know this place. And to get there we must cross the main trail to Vera Cruz. There is great danger if we expose ourselves on the open plain. We are men of the mountains – where we can attack and defend ourselves. If the French find us there in the open plain we will be slaughtered.”

“The one who came with me, Miguel, he knows this area very well. He will guide you safely. Then you must get together all the donkeys that you can. Miguel, and others, they watch the French at all times. He tells me that there are no large concentrations of French troops anywhere nearby. We can reach the coast at night without being seen. Once you get the guns you will be able to fight any smaller units that we may meet when we return. It can be done.”

“Yes, I suppose that this plan will work. We will get the weapons and use them to kill the British. But not for you or for your gringo friends. We fight for Juarez and Mexico – and for the day when this country will be free of all foreign troops.”

“I fight for that day as well,” O’Higgins said. “And we will win.”