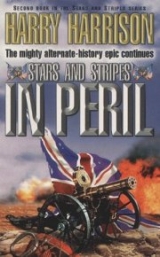

Текст книги "Stars and Stripes In Peril"

Автор книги: Harry Harrison

Жанр:

Альтернативная история

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

“If not the enemy’s port in Mexico,” Stanton called out angrily, “where the tarnation are we going?”

Lee looked around the table as the stunned silence lengthened. Then he leaned forward, put both hands flat on the table, then spoke one word.

“ Ireland,” Lee said, smiling beatifically upon the stunned men. “We are going to invade Ireland and free that country from the British yoke. I think that they will very quickly forget all about Mexico when they see our guns pointed at them from across the Irish Sea.”

Lincoln’s voice broke through the stunned silence.

“Now you have to admit, as the young lady said to the preacher, that there are some things in the world that you just shouldn’t talk about. When General Lee first told me of this deceit I felt as you do now. Overwhelmed. But the more you examine it the better it looks. We have here a plan of attack that is most audacious. But in order to succeed not a whisper of its existence must leak out. I am sure that you gentlemen can see why. Under the guise of one attack we must prepare another. The British will soon learn of our proposed Mexican invasion, certainly the coal ships and other preparations will be noticed. And the more they prepare for that battle the more unprepared they will be for our invasion of Ireland. Secrecy is our watchword, audacity our goal. It can be done – it will be done. General Lee will be happy to tell you how.”

THE SECRET PLAN

General Thomas Meagher was intensely tired. It had been a very rough Atlantic Ocean crossing from France, while the train from New York had taken most of the night to rattle uncomfortably to Washington City. He entered his tent and dropped into a chair, wearily began to pull off his boots. The only problem occupying his mind at this time was whether to change out of his civilian clothes before he fell asleep. Or maybe just drop onto his cot and get some well-deserved shut-eye. The decision was taken away from him when Captain Gossen poked his head in through the tent flaps.

“I wouldn’t get too comfortable if I were you, Tom. I’ve had a message on my desk for over a week now. You’re to report to General Robert E. Lee at the War Department, the instant you show up. Or earlier.”

Meagher groaned, then shouted for his horse to be saddled, sighed – and wearily pulled his boots back on. To better prepare himself for his visit – and perhaps burn away some of the fatigue – he downed a halftumbler of corn liquor before he went out.

They were indeed waiting for him at the War Department and a guide was instantly summoned. The soldier showed him the way to Room 313. There was a delay in admitting him, until Fox himself came out to identify him.

“General Meagher – just the man I want to see. Come on in.”

General Robert E. Lee was sitting at the long table working on a file of papers. He turned them face down before he stood and shook the Irishman’s hand.

“A pleasure to meet you, General Meagher. Come – let us get comfortable on the couch. Was your to trip Ireland a profitable one?”

Meagher looked to Fox before he answered: Fox nodded and spoke.

“General Lee knows all about your work in the Fenian Circle in the Irish Brigade. He knows as well all about your present attempts at the refounding of the Fenian Circle in Ireland.”

“In that case I can tell you that it went very well indeed, sir. Twelve more of my officers are on the way at this very moment to Dublin. Very soon now and we will have a network of cells established right across the country. And all completely safe and secure – and clear of informants.”

“That is very good to hear,” Lee said. “I want you to work very closely with me in the near future. I would greatly desire to put you on my staff, but that would draw unnecessary attention to you.”

Meagher was puzzled. He rubbed at his jaw and felt unshaven skin rasp against his fingertips. “I’m afraid that I miss your meaning, General.”

“Let me explain. Right now General Grant is leading an expeditionary force into Mexico to attack the British who are building that road that we are all so worried about. His first reports indicate that the enemy is well dug in and that attacking their defenses will be hard and bloody work. Still, we must increase the pressure on the British. You will soon be getting orders, and official reports, about an assault that will be building up to attack them, in order to force them out of Mexico. This will be done by our mounting a major attack on the Pacific end of their road across the isthmus.”

“Sure and that sounds a fine idea. Cut off the supply of troops and that will put paid to their invasion.”

“I am glad that you think so. You will keep saying just that to your officers and men. But you will never speak in public – or in private – about what I am going to tell you now. Nor will you reveal anything you learn here to your officers and men – no matter how tempted you are. Do you understand?”

“I’m not sure…”

“Than I shall elucidate. You will be one of the very few people who will know that the Mexican attack will never be carried out. It is in the nature of a ruse, a misdirection that will have the enemy looking just where we want them to look. Of course real plans, ship and troop movements, will be carried out. But we plan a totally different invasion. Do I have your word that you will reveal nothing that you hear in this room?”

“You have that, sir. I would swear that on the Holy Bible, if you had one here. I swear on the blessed Virgin Mary, the bloody wounds of Christ, and may the wild dogs of Brian Boru tear my throat out if I so much as breathe a word.”

“Yes, well, your word as an officer will do fine. Mr. Fox, if you please.”

Fox stood and took a key from his vest pocket and crossed the room. On the wall there was what appeared to be a wooden cabinet, at least a yard wide, but only a few inches thick. He unlocked the padlock that secured it, opened the door to disclose the map inside.

“This is our true target,” Lee said.

Meagher was on his feet, not believing his eyes.

“Holy Mother of God,” he whispered. “It’s Ireland! We are going to invade Ireland?”

“We are indeed. We shall free that land from the occupying forces, and bring Ireland democracy – just as we did in Canada.”

For the first time in recorded history Meagher was speechless. This was the cause that he had worked for all his adult life, what had always seemed such a lost cause. Were the dreams of the patriots down through the ages – were they to come true in his lifetime? It was unbelievable – but he had to believe it. The general had said it and there before his eyes was the Emerald Isle.

Meagher heard Lee’s voice as though it were coming from a great distance: he shook his head. Aware suddenly of the tears in his eyes. He dashed them away with the back of his hand.

“I’m sorry, General Lee, but it’s like a dream come true. A dream dreamt by every Irishman for hundreds and hundreds of years. Sure and my heart is bursting with joy and those tears were tears of gratitude. I thank you for what you are doing, thank you for the thousands of dead martyrs – and for all the Irishmen now living under the yoke of British tyranny. This is – so unexpected. You cannot understand…”

“I believe that I do. We fight to preserve American independence. If, in doing so, we can aid in fulfilling an Irish ambition that has been centuries in the making, we will be both honored and proud. Your homeland has given many of its sons to America. It is a pleasing thought that in defending our country we can aid a staunch ally, that has provided so many soldiers to the defense of this sovereign land. You, and your men, must be our eyes and our ears in Ireland. Yet there must be no suspicion that the military intelligence they are acquiring will be needed by the United States Army. Can this be done?”

Meagher could not sit still, so momentous were General Lee’s words. He jumped to his feet and paced the room, his thoughts atwirl. He slammed his fist over and over again into his palm, as though he could pummel the answer from his own flesh. Yes, yes – it was possible.

“It can be done. After all the Fenians are organized to plan a rebellion. Only this hope of eventual success has kept the movement alive. The men now working for the Fenian cause in Ireland are our eyes and ears. They all believe that the needed facts that they are gathering will be stored for that happy day when rebellion will be possible. But as you have said, only I will know that the information is being assembled for a larger and far more immediate use. It is more than possible, indeed it is what we would be doing in any case.”

“Admirable. There are many things that I must know before we can begin to plan an attack. An attack, remember, that cannot be allowed to fail. You must realize how precarious our position will be so far from these shores – and so close to England. Therefore the presence of our invading forces must be unseen, their existence unknown – until the moment the attack is launched. Our strike must be fast, accurate – and well-timed. If possible, victory must be in our grasp before our presence is known in England. For once we attack, and win, we must still be prepared for an immediate counterattack by the enemy. We will run great risks. But if – when – we succeed it will be a great and historical victory.”

“That it will be, General. And every manjack of us in the Irish Brigade is willing to shed his blood to bring about that glorious day.”

“If we plan well enough it will be the British blood that will be shed. Now, enlighten me about your country. All I see before me is a map of an island. I ask you to populate that map with people, to tell me of their cities and their history. All I know is that this history is a violent one.”

“Violence! Invasion! Where do I begin, for it is a history of murder and deceit in the past – and the particularly vile existence of the Plantations in the present. The English have always been a plague on Ireland, but it was that monster Cromwell who fell on this country like some demon from hell. The clearances began, clearing the Irish from their own homes. Took off the thatched roofs of the cottages, his Roundheads did, turned the population of Ireland out of their homes and onto the roads. There are no gypsies in Ireland – but there are our tinkers. The descendants of those Cromwell made homeless, Irish doomed to roam those muddy roads forever. Yet to never arrive.”

Lee nodded and made some notes on the papers before him. “You mentioned the Plantations. Surely you do not mean sugar or cotton plantations?”

“Not those. I mean the turning out of Roman Catholic Irishmen from their homes in Ulster, to hand these vacated premises over to Protestants from Scotland. An enemy tribe implanted so cruelly in our midst. You can tell it by the names! Every city in Ireland has a location, a portion of that city that is named Irishtown. Where those true Irish live who were turned out of their homes.”

“Then your planned rebellion is a religious rebellion. Catholic Irish against the English and their Protestant allies?”

“Not a bit of that. There has always been a Protestant presence in Ireland. Some of her greatest patriots have been of the Protestant faith. But, yes, there are hard and cruel men here in the north, here in Ulster. I remember one of the bits we had to memorize, drilled into us by the priests in school. It was an Englishman who said it, a famous man of letters. ‘I never saw a richer country, or, to speak my mind, a finer people.’ That’s what he said. But he went on – ‘the worst of them is the bitter and envenomed dislike which they have to each other. Their factions have been so long envenomed, and they have such narrow ground to do battle in, that they are like people fighting with daggers in a hogshead.’ Sir Walter Scott himself said that, as long ago as 1825.”

Meagher walked over and touched Belfast, drew a circle around it with his finger. “They are right good haters, they are. They hate the Pope in Rome, just as they love that plump little German lady who sits on the throne. A hatred that has lasted for centuries. But you shouldn’t be asking me – I’ve never been north myself. The man that you should talk to is the doctor in our Irish Brigade. Surgeon Francis Reynolds. He is from Portstewart in Derry, right up north on the coast. But he studied medicine in Belfast, then practiced there for some years. He’s your man if you want to know about the doings in Ulster.”

“Is he reliable?” Lee asked.

“The stoutest Fenian among us!”

Lee scribbled a quick note as he spoke. “Special consideration then for Belfast and the North. Consider consultation with Surgeon Reynolds. Now – what about the British military presence in Ireland?”

“Usually there are twenty to thirty thousand British troops in the country at any one time. Their biggest concentration is here, in the Curragh, a high plain south of Dublin. Plenty of soldiers there, mixed up with the sheep farmers. There has always been occupying troops stationed there since time began – but now they have brick buildings and an offensive permanent presence.”

“And elsewhere?”

“In Belfast of course. And Dublin, in the Castle, Cork in the south and more here and here.”

Lee joined him before the map. “Roads – and trains?”

“Almost everything runs out of Dublin. North to Belfast. Then the other trains go south from Dublin along the coast to Cork. Going west from Dublin across the Shannon to Galway and Kerry. Ah, and it’s a lovely coast there, the flowering bogs, the blue rivers.”

Lee looked more closely at the map, then ran his finger along a line of track. “You didn’t mention this line,” he said. “This track doesn’t connect with Dublin.”

“Indeed not, that’s the local line connecting Limerick with Cork. The same as this one in the north between Derry, Coleraine and Belfast.”

Meagher smiled, his eyes half-closed, seeing not the map but the country he had been cruelly exiled from.

Would the dream of freedom, dreamt by the Irish for centuries – would it finally be coming true?

Brigadier Somerville trotted his horse down the center of the road. The beast was lathered with sweat even though he had walked him most of the way, with only an occasional trot where the surface was flat and firm. It was the damnable and eternal heat. He passed a company of Sepoy troops digging an irrigation ditch beside the road. Men more suited to this climate than we would ever be. There was a group of officers up ahead grouped around a trestle table. They turned as he approached and he recognized their commanding officer.

“Everything going to plan, Wolseley?” he asked as he dismounted. He returned the officer’s salute.

“Doing very well since you left, General.”

Colonel Garnet Wolseley, Royal Engineers, was in command of the building of the road. He pointed to the raw earth of the cutting and at the smooth surface of the road below. “Been grading up to a mile a day since we got some men back from the defenses. Took longer than expected to revet the guns. The defenses are as good now as they ever will be. Then, of course, it takes far fewer troops to man them than it did to build them. With the road in good shape we can quickly move troops to defend points under attack.”

“Heartening news indeed.”

“I sincerely hope that I am not presumptuous in asking how the bigger plan is proceeding? With my nose buried in the mud here I know little of the world outside.”

“Then be cheered that everything proceeds just as planned. The transports are being assembled now in ports right around the coast of the British Isles. Even as the last troops depart from India. The Intrepid, sister ship of Valiant, is off the ways and being outfitted for battle. When all is ready we strike…”

He stopped and cocked his head at the distant rumble of gunfire. “An attack?” he asked. Wolseley shook his head.

“I doubt if it is a major one. From the sound of it, it is one of their probing efforts. They are seeing how well we are defending a particular section of the line.”

Bugles were sounding and a regiment of Gurkhas was assembled. They trotted briskly off towards the sound of the guns. Somerville spurred his horse in their wake. The firing grew steadily louder until the thunder of the guns was joined by the sound of shells screaming above their heads. He drew up by a company of red-coated soldiers standing at ease. One of them was ordered to hold his horse as he dismounted. The captain in command saluted him.

“Just cannon so far, sir. We are returning their fire. It’s not the first time that this has happened. But if they do commit troops we are right here in support. Their general is a stubborn man. He tries to wear us down with his constant battering. Then, if he feels that there is a possible opportunity, he probes forward with his troops.”

“You have a bulldog of an opponent out there. The American papers are full of it. Ulysses S. Grant, the man who never fails.”

“Well he is going to fail here if this is the best he can come up with.”

“I sincerely hope that you are correct, Captain. I think that I would like to see for myself how the attacks are faring.”

The captain led the way up the steep path towards the summit of the defenses. Cannon roared close by on both sides.

“Best not to go too far,” the captain said. “Their sharpshooters are most deadly. But you can see clearly from the embrasure.”

A gun fired from a pit nearby. Sweating gunners, naked to the waist, heaved it back so they could reload.

“Hold your fire,” Somerville ordered as he stepped past the gun to peer through the opening in the wall of logs through which they were firing. There was little enough to see down the glacis. Just a band of matted, dead vegetation – and then the jungle. A cannon fired from concealment, though the cloud of smoke betrayed its position. The ball hit the angled soil outer wall and screamed away overhead.

Somerville smiled. Everything was going exactly to plan.

BEHIND ENEMY LINES

Before the beginning of the Civil War, Allister Paisley had been close to starvation far too often. He had stepped off the immigrant ship from England in 1855, less than ten years earlier, feeling an immense relief when he first trod on American soil. Not that he really liked his new home – in fact he rather detested it. Certainly he would never have voluntarily crossed the ocean to settle in this crude and grubby land. It was the bailiffs who were just a few steps behind him that had prompted his unplanned emigration from Britain’s shore. Something of the very same kind had happened some years earlier in Scotland, which he had left hurriedly for much the same reasons he had fled England. What the offenses were remained known only to himself, the authorities, and the police. He had no friends to confide in – nor did he want any. He was a bitter and lonely man, a petty swindler and thief, who could not succeed for any length of time even in those unlovely arts.

His first bit of luck in America came when they were disembarking from the ship. He had climbed up from steerage into the cold light of day and, for the first time, had found himself almost separated from his equally penurious and foul-smelling fellow passengers. In the confusion on deck he had managed to mingle with the better-dressed passengers, even getting close enough to one of them to lift his pocket watch. The cry of thief sounded behind him – but by then he was safely ashore. By instinct he found his way to the slums of lower Manhattan, and to the pawnshop there. The uncle had cheated him in the exchange, yet he still had enough of the grubby banknotes and strange-looking coins to drink himself to extinction: at this time drinking being his single pleasure and vice.

Again a benevolent providence had smiled upon him. Before he was too drunk to render himself unconscious, he became aware that the man seated near him in the bar had stepped out of the back door to relieve himself. Paisley had dim memories that the stranger had pushed something under the bench when he had sat down. He shuffled sideways on the seat and felt down under it. Yes, a case of some kind. At that moment no one appeared to be looking in his direction. He seized the case by the handle, rose and slipped out the front door without being detected. When he had turned enough corners, and put some distance between himself and the drinking establishment, he paused on a rubbish-strewn bit of wasteland and opened the case.

Fortune had indeed smiled upon him. This was the sample case of a traveler in patent medicines. The principal medicine was Fletcher’s Castoria, a universal cure for childhood diseases and other ailments. The proud motto displayed on every label read “Children cry for it.” As well they might, since it was principally alcohol laced with a heady amount of opium. Paisley became an instant addict – but he did have the sense not to drink all of it, since this sample case was to be the key to a new life.

Travel was easy and cheap in this raw land, and opportunity ever knocking. The guise of a medicine traveler was a perfect cover for his petty crimes. He stole from his fellow travelers in cheap rooming houses, made easier by the American practice of sleeping four or five to a bed. He always rose before daylight and took anything that might be of value with him. That, along with shoplifting and some burglary, kept him alive – until the advent of war provided the perfect opportunity for the employment of his particular skills.

It was a matter of money and had nothing to do with slavery or Southern rights. It was just a matter of chance that he had been in Richmond, Virginia, when he read about the shelling of Fort Sumpter. If he had been in New York City he would have worked for the Federal government. As it was he went searching for the nearest military establishment. In the hectic environment of the opening days of the war, it took some time to find anyone who would listen to him. But he was persistent and in the end he found the ready ear of a military officer, a man who recognized the unique opportunity that this stranger with the thick accent represented.

Therefore Allister Paisley became almost the first spy employed by the South.

It had been a good war for him, as he shuttled back and forth between the warring sides. His Scotch accent and his medical flasks ensured that he was never suspected of his true employment. He brought his samples to the attention of the sutlers who accompanied every regiment and encampment. He soon discovered that the soldiers of the North shared his love of alcoholic beverages. Since they had little or no money, they were forced back on their own devices and brewed and fermented a number of noxious beverages. After he had discovered this fact yeast, raisins and other dried fruit were an essential part of his baggage. Money rarely changed hands; drink always did. Aching head, shaking limbs and painful regurgitation was the price he paid for his information. The names and numbers of regiments, guns and marching orders, all things military were patiently recorded and transcribed. The thin slips of paper traveled safely in a corked vial that was concealed inside a larger dark bottle of Fletcher’s Castoria. His dark secret was never discovered.

Also in the vial was a pass signed by General Robert E. Lee himself. When Paisley was back safely behind the Southern lines, this assured him rapid transportation to his employers in Richmond. After receiving his payment he drank more potable alcoholic beverages, until poverty, or military necessity, sent him forth once again.

When the newspapers printed the reports of the Trent affair and the ultimatum from Britain, he saw the opportunity to widen the scope of his activities. He knew the English very well, and also knew how to prize money from their grasp. Making his way to Washington City he easily found the residence of Lord Lyons, the British representative in the American capital. At an appropriate moment, when he knew that his lordship was at home, he managed to talk his way into his presence. Lyons appreciated the fact that if war did come, then a spy like MacDougal would be most useful to have. That was the name the Scotsman had given him, on the chance that police warrants were still extant.

War, happily for Paisley, did come, and he effortlessly changed sides and masters. It was in this new service that he found himself on the waterfront in Philadelphia, renewing an old acquaintance.

Horst Kretschmann, like his Scottish employer, felt no love for his adopted land. He was the proprietor of a very seedy drinking establishment, close to the Philadelphia Navy Yard. Here he brewed his own beer, which was very strong as well as being quite revolting. Since it was very cheap his customers did not complain. But they did talk to each other as they grew quickly drunk on his repulsive brew. Horst paid close attention to what they said, each night transcribing what he had learned in his scuffed, leather-bound diary. His notes entered in tiny, spidery writing in his native Bavarian dialect. Now, with the Civil War at an end, he had assumed he would never meet his paymaster again. Therefore he was quite pleased to see the Schotte appear one morning when he was swabbing out the drinking house floor.

“I didn’t expect to see you here, what with the war over.”

Paisley did not answer until the door was closed and bolted behind them.

“We’re still at war, aren’t we?”

“Are we?” He brought out a bottle of Schnaps and put it on the table; neither of them would drink the repugnant beer. “Didn’t we send the British away with their tails between their legs?”

“I guess so – but they’re a tenacious breed. And pay well for news.”

“That is very good to hear. Prosit.”

Horst smacked his lips and refilled their glasses.

Paisley drained his and belched loudly: the German nodded approval.

“Any talk among the sailors?” Paisley asked.

“Not much. Not many ship movements since the end of the war. But they complain, sailors always complain. It’s about the coal dust now, aboard the Dictator. Got her bunkers full and still more bags in the companionways.” Paisley was interested.

“A long journey then. Any idea where?”

“None of them seemed to know. But there are three coaling ships now loading at the docks. The Schwarzen who load, they drink in here.”

“Do they know anything?”

“Yes – but it is hard to understand them. Still one did mention South America.”

Paisley nodded as he took a roll of greasy dollar bills from his pocket. With this, and the troop movements he had already recorded, he had enough for a report. Just in time since the Primevère sailed in two days for Belgium. It would take him that long to transcribe the clumsy substitution code using the Bible.

For Patrick Joseph Condon this was a homecoming he had not expected. He had fled Dublin in 1848, with the Royal Irish Constabulary and the soldiers right behind him. The uprising planned by the Young Islanders had failed. O’Brian, as well as Meagher and McManus, had been seized and sentenced to transportation for life to Tasmania. But Condon had been warned in time, had fled through a back window with nothing but the clothes on his back. A good deal had happened to him since then. Now he was a captain in the United States Army and on a very different mission indeed.

Dublin had not changed. Walking into the city from Kingstown was a travel back through time. Through the hovels of Irishtown and past Trinity College. He had studied there, but had left to join the uprising. He looked through the railings as they passed along Nassau Street; it was just as he remembered. They crossed Ha’penny Bridge, paying the toll, then walked down the quays along the Liffy. Memories.

But this was all very new for James Gallagher, who was walking beside him. Brought up in a small village in Galway, he had memories only of hunger, and the cold winds of winter blowing in from the Atlantic. He had been fifteen years old when they had emigrated to America, with tickets sent by his brother in Boston. Now, just turned twenty, he was a private in the American army and not quite sure exactly what he was doing back here in Ireland. All he knew was that every man in the Irish Brigade had been asked to write down where he came from in Ireland. There had been a score of them from Galway and, for some reason unknown to him, he had been selected. Although there were many who were brighter than him, bolder even, and eager to see Ireland again, who might have been selected. But he was the only one who had an uncle who worked as an engine driver. He was unhappy about this selection, and frightened, trying not to shiver whenever they passed a man in uniform.

“Are we getting close, sir? Jayzus but it’s a divil of a way…”

“Very close now, Jimmy. That’s Arran Quay right up ahead there. The shop should be easy to find.”

No sign was visible on the grubby premises, but the worn clothing hanging outside was identification enough. Their smart clothing would draw no attention in Dublin. But once out of the city heads would turn, notice would be taken – which was the last thing that they wanted. They bent under the rack of pendant garments and entered the darkness of the shop. When they emerged, some minutes later, dressed in worn, gray clothing they were one with the other impoverished citizens of the land. Condon carried a battered cardboard valise, tied together with string. Gallagher had all of his belongings in a stained potato sack.

They continued on to Kingsbridge Station where Condon bought them Third Class tickets to Galway. Although they drew no particular notice, they were both very relieved when the steam engine sounded its whistle and the train pulled out slowly, clicking across the points, going west.

Condon read a pennydreadful that he had picked up in the train station in Holyhead: Gallagher looked out of the window at the green Irish countryside drifting by and wished very much that he was back in the army. He knew that he had complained and skived along with the rest of the soldiers. He swore that he would not complain ever again, if he got safely back from this terrifying ordeal.