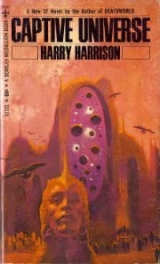

Текст книги "Captive Universe"

Автор книги: Harry Harrison

Соавторы: Harry Harrison

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

He nodded, in pain, in the darkness, and could not speak. Her words were true enough: there was no escape from this valley. He held her once, to comfort her, the way she used to hold him when he was small, until she gently pushed him away. “Go now,” she said, “and I will return to the village.”

Quiauh waited in the doorway until his stumbling figure had vanished into the endless night, then she turned and quietly went back down the stairs to his cell. From the inside she pulled the bars back into place, though she could not seal them there, then seated herself against the far wall. She felt about the stone floor until her fingers touched the bindings she had removed from her son. They were too short to tie now, but she still wrapped them around her wrist and held the ends with her fingers. One piece she placed carefully over her ankles.

Then she sat back, placidly, almost smiling into the darkness.

The waiting was over at last, those years of waiting. She would be at peace soon. They would come and find her here and know that she had released her son. They would kill her but she did not mind.

Death would be far easier to bear.

8

In the darkness someone bumped into Chimal and clutched him; there was an instant of fear as he thought he was captured. But, even as he made a fist to strike out he heard the man, it might even be a woman, moan and release him to run on. Chimal realized that now, during this night, everyone would be just as afraid as he was. He stumbled forward, away from the temple with his hands outstretched before him, until he was separated from the other people. When the pyramid, with the flickering lights on its summit, was just a great shadow in the distance he dropped and put his back against a large boulder and thought very hard.

What shall I do? He almost spoke the words aloud and realized that panic would not help. The darkness was his protection, not his enemy as it was to all the others, and he must make good use of it. What came first. Water, perhaps? No, not now. There was water only in the village and he could not go there. Nor to the river while Coatlicue walked. His thirst would just have to be forgotten: he had been thirsty before.

Could he escape this valley? For many years he had had this thought somewhere in the back of his mind, the priests could not punish you for thinking about climbing the cliffs, and at one time or another he had looked at every section of wall of the valley. It could be climbed in some places, but never very far. Either the rock became very smooth or there was an overhang. He had never found a spot that even looked suitable for an attempt.

If he could only fly! Birds left this valley, but he was no bird. Nothing else escaped, other than the water, and he was not water either. But he could swim in water, there might be a way out that way.

Not that he really believed this. His thirst may have had something to do with the decision, and the fact that he was between the temple and the swamp and it would be easy to reach without meeting anyone on the way. There was the need to do something in any case, and this was the easiest way. His feet found a path and he followed it slowly through the darkness, until he could hear the night sounds of the swamp not far ahead. He stopped then, and even retraced his steps because Coatlicue would be in the swamp as well. Then he found a sandy spot off the path and lay down on his back. His side hurt, and so did his head. There were cuts and bruises over most of his body. Above him the stars climbed and he thought it strange to see the summer and fall stars at this early time of the year. Birds called plaintively from the direction of the swamp, wondering where dawn was, and he went to sleep. The familiar spring constellations had returned, so an entire day must have passed without the sun rising.

From time to time he awoke, and the last time he saw the faintest lightening in the east. He put a pebble into his mouth to help him forget the thirst, then sat up and watched the horizon.

A new first priest must have been appointed, probably Itzcoatl, and the prayers were being said. But it was not easy; Huitzilopochtli must be fighting very hard. For a long time the light in the east did not change, then, ever so slowly it brightened until the sun rose above the horizon. It was a red, unhappy sun, but it rose at last. The day had began and now the search for him would begin as well. Chimal went over the rise to the swamp and, splashed into the mud until the water deepened, then pushed aside the floating layer of green with his hands and lowered his face to drink.

It was full daylight now and the sun seemed to be losing its unhealthy reddish cast as it climbed triumphantly up into the sky. Chimal saw his footprints cutting through the mud into the swamp, but it did not matter. There were few places in the valley to hide and the swamp was the only one that could not be quickly searched. They would be after him here. Turning away, he pushed through the waist-high water, heading deeper in.

He had never been this far into the swamp before, nor had anyone else that he knew of, and it was easy to see why. Once the belt of clattering reeds had been crossed at the edge of the water the tall trees began. They stood above the water, on roots like many legs, and their foliage joined overhead. Thick gray growths hung from their branches and trailed in the water, and under the matted leaves and streamers the air was dark and stagnant. And thick with insect life. Mosquitoes and gnats filled his ears with their shrill whining and sought out his skin as he penetrated into the shadow. Within a few minutes his cheeks and arms were puffing up and his skin was splotched with blood where he had smashed the troublesome insects. Finally he dug some of the black and foul-smelling mud from the bottom of the swamp and plastered it onto his exposed skin. This helped a bit, but it kept washing off when he came to the deeper parts and had to swim.

There were greater dangers as well. A green water snake swam toward him, its body wriggling on the surface and its head high and poison fangs ready. He drove it off by splashing at it, then tore off a length of dry branch in case he should encounter more of the deadly reptiles.

Then there was sunlight before him and a narrow strip of water between the trees and the tumbled rock barrier. He climbed out onto a large boulder, grateful for the sun and the relief from the insects.

Swollen black forms, as long as his finger and longer, hung from his body, damp and repellent looking. When he clutched one it burst in his fingers and his hand was suddenly sticky with his own blood. Leeches. He had seen the priests use them. Each one had to be pried off carefully and he did this, until they were all gone and his body was covered with a number of small wounds. After washing off the blood and fragments of leech he looked up at the barrier that rose above him.

He would never be able to climb it. Lips of great boulders, some of them as big as the temple, projected and overhung one another. If one of them could be passed the others waited. Nevertheless it had to be tried, unless a way could be found out at the water level, though this looked equally hopeless. While he considered this he heard a victorious shout and looked up to see a priest standing on the rocks just a few hundred feet away. There were splashes from the swamp and he turned and dived back into the water and the torturous shelter of the trees.

It was a very long day. Chimal was not seen again by his pursuers, but many times he was surrounded by them as they splashed noisily through the swamp. He escaped by holding his breath and hiding under the murky water when they came near, and by staying in the densest, most insect-ridden places that they were hesitant to penetrate. By the late afternoon he was near exhaustion and knew he could not go on very much longer. A scream, and even louder shouting, saved his life – at the expense of one of the searchers. He had been bitten by a water snake, and this accident took the heart out of the other hunters. Chimal heard them moving away from him and he remained, hidden, under an overhanging limb with just his head above the water. His eyelids were so swollen from insect bites that he had to press them apart with his fingers to see clearly.

“Chimal,” a voice called in the distance, then again, “Chimal… We know you are in there, and you cannot escape. Give yourself to us because we will find you in the end. Come now…”

Chimal sank lower in the water and did not bother to answer. He knew as well as they did that there was no final escape. Yet he would still not give himself up to their torture. It would be better to die here in the swamp, die whole and stay in the water. And keep his heart.

As the sky darkened he began to work his way carefully toward the edge of the swamp. He knew that none of them would stay in the water during the night, but they might very well lie hidden among the rocks nearby to see him if he emerged and tried to escape. Pain and exhaustion made thinking difficult, yet he knew he had to have a plan. If he stayed in the deep water he would surely be dead by morning. As soon as it was dark he would go into the reeds close to shore and then decide what to do next. It was hard to think.

He must have been unconscious for some tune, there near the water’s edge, because when he forced his swollen eyelids open with his fingertips he saw that the stars were out and that all traces of light had vanished from the sky. This troubled him greatly and in his befuddled state he could not be sure why. A breeze stirred the reeds so that they rustled behind him. Then the motion died away and for a moment the air held a hushed evening silence.

At this instant, far off to the left in the direction of the river, he heard an angry hissing.

Coatlicue!

He had forgotten her! Here he was near the river at night, in the water, and he had forgotten her!

He lay there, paralyzed with fear, as a sudden rattle of gravel and running footsteps sounded on the hard ground. His first thought was Coatlicue, then he realized that someone had been hidden close by among the rocks, waiting to take him if he emerged from the swamp. Whoever it was had also heard Coatlicue and had run for his life.

The hissing sounded again, closer.

Since he had escaped in the swamp all day – and since he knew there were men lying in wait for him on shore – he pulled himself slowly back into the water. He did it without thinking: the voice of the goddess had driven all thought from his mind. Slowly, making not a sound, he backed up until the water reached to his waist.

And then Coatlicue appeared over the rise, both heads looking toward him and hissing with loud anger, while the starlight shone on the outstretched claws.

Chimal could not look anymore at his own death; it was too hideous. He took a deep breath and slipped under the water, swimming to keep himself below the surface. He could not escape this way, but he would not have to watch as she trod through the water toward him, then plunged down her claws like some monstrous fisher and pulled him to her.

His lungs burned and still she had not struck. When he could bear it no longer he slowly raised his head and looked out at the empty shore. Dimly, upriver in the distance, there was the echo of a faint hissing.

For a long time Chimal just stood there, the water streaming from his body, while his befuddled mind attempted to understand what had happened. Coatlicue was gone. She had come for him and he had hidden under the water. When he had done this she could not find him so she had gone away.

One thought cut through the fatigue and lifted him so that he whispered it aloud.

“I have outwitted a god…”

What could it all mean? He went out of the water and lay on the sand that was still warm from the day and thought about it very hard. He was different, he had always known that, even when he was working hard to conceal the difference. He had seen strange things and the gods had not struck him down – and now he had escaped Coatlicue. Had he outwitted a god? He must have. Was he a god? No, he knew better than that. Then how, how…

Then he slept, restlessly, waking and sleeping again. His skin was hot and he dreamt, and at times he did not know if he was dreaming awake or asleep. He could have been taken then, easily, but the human watchers had been frightened away and Coatlicue did not return.

Toward dawn the fever must have broken because he awoke, shivering, and very thirsty. He stumbled to the shore and drank from his cupped hands and rubbed water onto his face. He felt sore and bruised from head to toe, so that the many little aches merged into one all-consuming pain. His head still rang with the effects of the fever and his thoughts were clumsy – but one thought kept repeating over and over like the hammering of a ritual drum. He had escaped Coatlicue. For some reason she had not discovered him in the water. Had it been that? It would be easy enough to find out: she would be returning soon and he could wait for her. Once the idea had been planted it burned in his brain. Why not? He had escaped her once – he would do it again. He would look at her again and escape again, that’s what he would do.

Yes, that is what he would do, he mumbled to himself, and stumbled off toward the west, following the edge of the swamp. This is where the goddess had first come from and this is where she might reappear. If she did, he would see her again. When the shoreline turned he realized that he had come to the river where it drained into the swamp, and prudence drove him back into the water. Coatlicue guarded the river. It would be dawn soon and he would be safe, far out here in the water with just his head showing, peering through the reeds.

The sky was red and the last stars were fading when she returned. Shivering with fear he remained where he was, but sank deeper into the water until just his eyes were above the surface. Coatlicue never paused but walked heavily along the riverbank, the snakes in her kirtle hissing in response to her two great serpents’ heads.

As she passed he rose slowly from the water and watched her go. She went out of sight along the edge of the swamp and he was alone, with the light of another day striking gold fire from the tops of the high peaks before him.

When it was full daylight he followed her.

There was no danger now, Coatlicue only walked by night and it was not forbidden to enter this part of the valley during the day. Elation filled him – he followed the goddess. He had seen her pass and here, beside the hardened mud, he could see signs of her passing. Perhaps she had come this way often because he found himself following what appeared to be a well trodden path. He would have taken it for an ordinary path, used by the men who came to snare the ducks and other birds here, if he had not seen her go this way. Around the swamp the path led, then toward the solid rock of the cliff wall. It was hard to follow on the hard soil and among the boulders, yet he found traces because he knew what to look for. Coatlicue had come this way.

Here there was a cleft in the rock where some ancient fissure had split the wall. Boulders rose on both sides and it did not seem possible that she had gone any other way unless she flew, which perhaps goddesses could do. If she walked she had gone straight ahead.

Chimal started into the rocky cleft just as a rolling wave of rattlesnakes and scorpions poured out of it.

The sight was so shocking, he had never seen more than one of these poisonous creatures at a time before, that he just stood there as death rustled close. Only his natural feelings of repulsion saved his life. He fell back before the deadly things and clambered up a steep boulder, pulling his feet up as the first of them swirled around the base. Drawing himself up higher he threw one hand over the summit of the rock – and a needle of fire lanced down his arm. He was not the first to arrive and there, on his wrist, the large, waxy-yellow scorpion had plunged its sting deep into his flesh.

With a gesture of loathing he shook it to the rock and crushed it under his sandal. More of the poisonous insects had crawled up the easy slope of the other side of the boulder and he stamped on them and kicked them back, then he bruised his wrist against the sharp edge of stone until it bled before he tried to suck out the venom. The greater pain in his arm drowned out all the other minor ones on his ravaged body.

Had that wave of nauseating death been meant for him? There was no way of telling and he did not want to think about it. The world he knew was changing too fast and all of the old rules seemed to be breaking down. He had looked on Coatlicue and lived, followed her and lived. Perhaps the rattlesnakes and the scorpions were one of her attributes that followed naturally after her, the way dew followed the night. He could not begin to understand it. The poison was making him lightheaded – yet elated at the same time. He felt as though he could do anything and that there was no power on Earth, above or below it, that could stop him.

When the last snake and insect had gone on or vanished among the crevices in the rocks, he slid carefully back to the ground and went on up the path. It twisted between great ragged boulders, immense pieces that had dropped from the fractured cliff, then entered the crevice in the cliff itself. The vertical crack was high, but not very deep. Chimal, following what was obviously a well-trodden path, found himself suddenly facing the wall of solid rock.

There was no way out. The trail led to a dead end. He leaned against the rough stone and fought to get his breath. This is what he should have suspected. Because Coatlicue walked the Earth in solid guise did not mean that she was human or had human limitations. She could turn to gas if she wanted to and fly up and out of here. Or perhaps she could walk into the solid rock which would be like air to her. What did it matter – and what was he doing here? Fatigue threatened to overwhelm him and his entire arm was burning from the insect’s poisonous bite. He should find a place to hide for the day, or find some food, do anything but remain here. What madness had led him on this strange chase?

He turned away – then jumped aside as he saw the rattlesnake. The snake was in the shadow against the cliff face. It did not move. When he came close he saw that it lay on its side with its jaws open and its eyes filmed. Chimal reached out carefully with his toe – and kicked at it. It merely flopped limply: it was surely dead. But it seemed to be, in some way, attached to the cliff.

Curious now, he reached out a cautious hand and touched its cool body. Perhaps the serpents of Coatlicue could emerge from solid rock just as she could enter it He tugged on the body, harder and harder until it suddenly tore and came away in his hand. When he bent close, and pressed his cheek to the ground, he could see where the snake’s blood had stained the sand, and the crushed end of the back portion of its body. It was squashed flat, no thicker than his fingernail, and seemed to be imbedded in the very rock itself. No, there was a hairline crack on each side, almost invisible in the shadows close to the ground. He put his fingertips against it and traced its long length, a crack as straight as an arrow. The line ended suddenly, but when he looked closely he saw that it went straight up now, a thin vertical fissure in the rock.

With his fingers he traced it up, high over his head, then to the left, to another corner, then back down again. Only when his hand had returned to the snake again did he realize the significance of what he had found. The narrow crack traced a high, four sided figure in the face of the cliff.

It was a door!

Could it be? Yes, that explained everything. How Coatlicue had left and how the snakes and scorpions had been admitted. A door, an exit from the valley…

When the total impact of this idea hit him he sat down suddenly on the ground, stunned by it. An exit. A way out. It was a way that only the gods used, he would have to consider that carefully, but he had seen Coatlicue twice and she had not seized him. There just might be a way to follow her from the valley. He had to think about it, think hard, but his head hurt so. More important now was thinking about staying alive, so he might be able later to do something about this earth-shaking discovery. The sun was higher in the sky now and the searchers must already be on their way from the villages. He had to hide – and not in the swamp. Another day there would finish him. Clumsily and painfully, he began to run back down the path toward the village of Zaachila.

There were wastelands near the swamp, rock and sand with occasional stands of cactus, with no place to hide in all their emptiness. Panic drove Chimal on now: he expected to meet the searchers coming from the village at any moment. They would be on their way, he knew that. Climbing a rocky slope he came to the outskirts of the maguey fields and saw, on the far side, the first men approaching. He dropped at once and crawled forward between the rows of broad-leaved plants. They were spaced a man’s height apart and the earth between them was soft and well tilled, Perhaps…

Lying on his side, Chimal scraped desperately with both hands at the loose soil, on a line between two of the plants. When he had scooped out a shallow, grave-like depression he crawled into it and threw the sand back over his legs and body. He would not be hidden from any close inspection, but the needle-tipped leaves reached over him and offered additional concealment Then he stopped, rigid, as voices called close by.

They were just two furrows away, a half a dozen men, shouting to each other and to someone still out of sight. Chimal could see their feet below the plants and their heads above.

“Ocotre was swollen like a melon from the water snake poison, I thought his skin would burst when they put him on the fire.”

“Chimal will burst when we turn him over to the priests—”

“Have you heard? Itzcoatl promises to torture him for an entire month before sacrificing him…”

“Only a month?” one of them asked as their voices faded from sight. My people are very fond of me, Chimal thought to himself, and smiled wryly up at the green leaf above his face. He would suck some of its juice as soon as they were gone.

Running footsteps sounded close by, coming directly toward him.

He lay, holding his breath, as they grew loud and a man shouted, right above the spot where he was hiding.

“I’m coming – I have the octli.”

It seemed impossible for him not to see Chimal lying there, and Chimal arched his fingers, ready to reach out and kill the man before he could cry for help. A sandal thudded close beside his head – then the man was gone, his footsteps dying away. He had been calling to the others and had never looked down. After this Chimal just lay there, his hands shaking, trying to force a way through the fog that clouded his thoughts, to make a coherent plan. Was there a way to enter the doorway in the rock? Coatlicue knew how to do it, but he shivered away from the idea of following close behind her or of hiding nearby in the rocks. That would be suicide. He reached up and tore a leaf from the maguey and, with one of its own thorns, he made thin slashes so the juice could run out. He licked at this and some time later he was still no closer to a solution to his problem than he had been when he began. The pain was ebbing from his arm and he was half dozing there in his bed of earth when he heard the hesitant shuffle of footsteps slowly coming near him.

Someone knew that he was here and was searching for him.

Cautiously, his fingers crept out and found a smooth stone that fitted neatly into his palm. He would not be easily taken back alive for that month of torture the priests had promised.

The man came into sight, bent low to take advantage of the concealment offered by the maguey plants and looking back over his shoulder as he went. Chimal wondered for a moment what this could mean – then realized that the man was escaping his duty in the swamp. Days of work in the fields had been lost already, and the man who did not work went hungry. This one was going off unseen to take care of his crops: in the confusion that existed in the swamp he would not be missed – and he was undoubtedly planning to return later in the afternoon.

As he came close Chimal saw that he was one of the lucky few in the valley who owned a corn knife made of iron. He held it loosely in one hand and when Chimal looked at it he had a sudden understanding of what he could use that knife for.

Without stopping to think it out he rose as the man passed him and struck out with the stone. The man turned, surprised, just as the stone struck him full in the side of the head. He fell limply to the ground and did not move again. When Chimal took the long, wide-bladed knife from his fingers he saw that the man was still breathing hoarsely. That was good: there had been enough killing. Bending just as low as the man from Zaachila had done he retraced his steps.

There was no one to be seen: the searchers must be deep into the swamp by now. Chimal wished them luck with the leeches and mosquitoes – though the priests were welcome to these discomforts, and perhaps some water snakes as well. Unseen, he slipped up the path between the rocks and once more found himself facing the apparently solid wall of rock.

Nothing had changed. The sun was higher now and flies buzzed about the dead snake. When he bent close he could see that the crack in the stone was still there.

What was inside – Coatlicue waiting?

That did not bear thinking about. He could die here, or he could die at her hands. Hers might even be a quicker death. This was a possible way out of the valley. He must see if he could use it.

The blade of the corn knife was too thick to be forced into the vertical cracks, but the gap below was wider, perhaps held open by the snake’s crushed body. He worked the blade in and pulled up on it. Nothing happened, the rock was still immobile rock. Then he tried pushing it in at different spots and levering harder: the results were the same. Yet Coatlicue was able to lift the rock door – why couldn’t he? He pushed deeper and tried again, and this time he felt something move. Harder now, harder, he pried up with all the strength of his legs. There was a loud crack and the knifeblade broke off in his hands. He staggered back, holding the worn wooden handle and looking in disbelief at the shining end of the metal stub.

This had to be the end. He was cursed by destruction and death, he saw that now. Because of him the first priest had died and the sun had not risen, he had caused trouble and pain and now he had even broken one of the irreplaceable tools that the people of the valley depended upon for survival. In an agony of self-contempt he jammed the remaining bit of blade under the door again – and heard excited voices on the path behind him.

Someone had found his spoor and had trailed him here. They were close and they would have him and he would be dead.

In anger and fear now he jabbed the broken stump into the crack, back and forth, hating everything. He felt a resistance to the blade and pushed harder, and something gave way. Then he had to fall back as a great table of rock, as thick as his body, swung silently out and away from the cliff.

Sitting there, all he could do was gape. A curved runnel stretched out of sight into the rock, carved from the solid stone. What lay beyond the curve was not visible.

Was Coatlicue waiting there for him? He had no time to think about it because the voices were closer now, just entering the crevice. Here was the exit he sought – why did he hesitate?

Still clutching the broken corn knife he fell through, scrambling on all fours. As he did this the rock door swung shut behind him as silently as it had opened. The sunlight diminished to a wedge, a crack, a hairline of light – then vanished.

Chimal turned, his heart beating louder than a sacrificial drum in his chest, to face the blackness there.

He took a single, hesitating step forward.