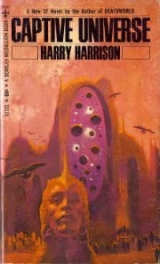

Текст книги "Captive Universe"

Автор книги: Harry Harrison

Соавторы: Harry Harrison

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

5

Someone passed a cup of octli and Chimal buried his face in it, breathing in the sour, strong odor, before he drank. He was alone on the newly woven grass mat, yet was surrounded on all sides by noisy members of his and Malinche’s clans. They mixed, talked, even shouted to be heard, while the young girls were busy with the jugs of octli. They sat in the sandy area, now swept clean, that was in the center of the village, and it was barely big enough to hold them all. Chimal turned and saw his mother, smiling as he had not seen her smile in years, and he turned away so quickly that the octli slopped over onto his tilmantl, his marriage cloak new and white and specially woven for the occasion. He brushed at the sticky liquid – then stopped as a sudden hush came over the crowd.

“She is coming,” someone whispered, and there was a stir of motion as everyone turned to look. Chimal stared into the now almost empty cup, nor did he glance up when the guests moved aside to let the matchmaker by. The old woman staggered under the weight of the bride to be, but she had carried burdens all her life and this was her duty. She stopped at the edge of the mat and carefully let Malinche step onto it. Malinche also wore a new white cloak, and her moon face had been rubbed with peanut oil so that her skin would glisten and be more attractive. With shifting motions she settled into a relaxed kneeling position, very much like a dog making itself comfortable, and turned her round eyes to Cuauhtemoc who rose and spread his arms impressively. As leader of the groom’s clan he had the right to speak first. He cleared his throat and spat into the sand.

“Here we are together for an important binding of the clans. You will remember that when Yotihuac died during the hunger of the time when the corn did not ripen, he had a wife and her name is Quiauh and she is here among us, and he had a son and his name is Chimal and he sits here on the mat…”

Chimal did not listen. He had been to other weddings and this one would be no different. The leaders of the clans would make long speeches that put everyone to sleep, then the matchmaker would make a long speech and others who felt moved by the occasion would also make long speeches. Many of the guests would doze and much octli would be drunk, and finally, when it was almost sunset, the knot would be tied in their cloaks that would bind them together for life. Even then there would be more speeches. Only when it was close to dark would the ceremony end and the bride would go home with her family. Malinche also had no father, he had died from a bite by a rattlesnake the year before, but she had uncles and brothers. They would take her and many of them would sleep with her that night. Since she was of their clan it was only fair that they save Chimal from the ghostly dangers of marriage by taking whatever curses there were unto themselves. Only on the next night would she move into his house.

He was aware of all these things and he did not care. Though he knew that he was young, at this moment he felt that his days were almost over. He could see the future and the rest of his life as clearly as if he had already lived it, because it would be unchanging and no different from the lives of all the others around him. Malinche would make his tortillas twice a day and bear a child once a year. He would plant the corn and reap the corn and each day would be like every other day and he would then be old, and very soon after that he would be dead.

That was the way it must be. He held his hand out for more octli and his cup was refilled. That was the way it would be. There was nothing else, and he could not think of anything else. When his mind veered away from the proper thoughts that he should be thinking he quickly dragged them back and drank some more from his cup. He would remain silent, and empty his mind of thoughts. A shadow swept across the sand and touched them with a passing moment of darkness as a great vulture landed on the rooftree of a nearby house. It was dusty and tattered and, like an old woman arranging her robe, it moved its wings and waddled back and forth as it settled down. First it looked at him with one cold eye, then with the other. Its eyes were as round as Malinche’s and just as empty. Its back was wickedly curved and, like the feathers of its ruff, stained with gore.

It was later and the vulture had long since departed. Everything here was too alive: it wanted its meat safely dead. The long ceremony was finally drawing to its end. The leaders of both clans came forward solemnly and laid hands on the white tilmantli, then prepared to tie the marriage cloaks together. Chimal blinked at the rough hands that fumbled with the corner of the fabric and, in an instant, from nothing to everything, the red madness possessed him. It was the way he had felt that day at the pool only much stronger. There was only one thing that could be done, a single thing that had to be done, and no other course was possible to take.

He jumped to his feet and pulled his cloak free of the clasping fingers.

“No, I won’t do it,” he shouted in a voice roughened by the octli he had drunk. “I will not marry her or anyone else. You cannot force me to.”

He strode away in the dusk through a shocked silence and no one thought to reach out and stop him.

6

If the people of the village were watching, they did not reveal themselves. Some of the door covers stirred in the breeze that had sprung up just after dawn, but nothing moved in the darkness behind them.

Chimal walked with his head up, stepping out so strongly that the two priests in their ground-length cloaks had trouble keeping pace with him. His mother had cried out when they had come for him, soon after daybreak, a single shout of pain as though she had seen him die at that moment. They had stood in the doorway, black as two messengers of death, and had asked for him, their weapons ready in case he should resist. Each of them carried a maquahuitl, the deadliest of all the Aztec weapons: the obsidian blades that were set into the hardwood handle were sharp enough to sever a man’s head with a single blow. They had not needed this threat of violence, quite the opposite in fact. Chimal had been behind the house when he heard their voices. “To the temple then,” he had answered, throwing his cloak over his shoulders and knotting it while he walked. The young priests had to hurry to catch up.

He knew that he should be walking in terror of what might await him at the temple, yet, for some unaccountable reason, he was elated. Not happy, no one could be happy when going to face the priests, but so great was his feeling of rightness that he could ignore the dark shadow of the future. It was as though a great burden had been lifted from his mind and, in truth, it had. For the first time, since he had been a small child, he had not lied to conceal his thoughts: he had spoken out what he knew to be true in defiance of everyone. He did not know where it would end, but at this instant did not really care.

They were waiting for him at the pyramid and there was no question now of his walking on alone. The priests blocked his way and two of the strongest took him by the arms: he made no attempt to free himself as they led him up the steps to the temple on the summit He had never entered here before; normally only priests passed through the carved doorway with its frieze of serpents disgorging skeletons. When they paused at the entranceway some of his elation seeped out before this ominous prospect. He turned away from it to look out across the valley.

From this height he could see the entire length of the river. From the grove of trees to the south it emerged and meandered between the steep banks, cutting between the two villages, then laid a course of golden sand until it vanished into the swamp near at hand. Beyond the swamp rose the rock barrier and he could see more tall mountains in the distance…

“Bring the one in,” Citlallatonac’s voice spoke from the temple, and they pushed him inside.

The first priest was sitting cross-legged on an ornamented block of stone before a statue of Coatlicue. In the half light of the temple the goddess was hideously lifelike, glazed and painted and decorated with gems and gold plates. Her twin heads looked at him and her claw-handed arms appeared ready to seize.

“You have disobeyed the clan leaders,” the first priest said loudly. The other priests stepped back so that Chimal could approach him. Chimal came close, and when he did so he saw that the priest was older than he had thought. His hair, matted with blood and dirt and unwashed for years, had the desired frightening effect, as did the blood on his death-symboled robe. But the priest’s eyes were sunk deep into his head and were watery red: his neck was as scrawny and wrinkled as that of a turkey. His skin had a waxy pallor except where patches of red powder had been dusted on his cheeks to simulate good health. Chimal looked at the priest and did not answer.

“You have disobeyed. Do you know the penalty?” The old man’s voice cracked with rage.

“I did not disobey, therefore there is no penalty.” The priest half rose with astonishment when he heard these calmly spoken words, then he dropped back and huddled down, his eyes narrowed with anger. “You spoke this way once before and you were beaten, Chimal. You do not argue with a priest.”

“I am not arguing, revered Citlallatonac, but merely explaining what has happened…”

“I do not like the sound of your explaining,” the priest broke in. “Do you not know your place in this world? You were taught it in the temple school along with all the other boys. The gods rule. The priests interpret and interpose. The people obey. Your duty is to obey and nothing else.”

“I do my duty. I obey the gods. I do not obey my fellow men when they are at odds with the word of the gods. It would be blasphemy to do that, the penalty for which is death. Since I do not wish to die I obey the gods even though mortal men grow angry at me.”

The priest blinked, then picked a bit of matter from the corner of one eye with the tip of his grimy forefinger. “What is the meaning of your words,” he finally said, and there was a touch of hesitancy in his voice. “The gods have ordered your wedding.”

“That they have not – men have done that. It is written in the holy words that man is to marry and be fruitful and woman is to marry and be fruitful. But it does not say what age they should be married at, or that they must be forced to marry against then: will.”

“Men marry at twenty-one, women at sixteen…”

“That is the common custom, but only a custom. It does not have the weight of law…”

“You argued before,” the priest said shrilly, “and were beaten. You can be beaten again…”

“A boy is beaten. You do not beat a man for speaking the truth. I ask only that the law of the gods be followed – how can you punish me for that?”

“Bring me the books of the law,” the first priest shouted to the others waiting outside. “This one must be shown the truth before he is punished. I remember no laws like these.”

In a quiet voice Chimal said, “I remember them clearly. They are as I have told you.” The old priest sat back, blinking angrily in the shaft of sunlight that fell upon him, The bar of light, the priest’s face, stirred Chimal’s memory and he spoke the words almost as a dare. “I remember also what you told us about the sun and the stars, you read from the books. The sun is a ball of burning gas, didn’t you say that, which is moved by the gods? Or did you say the sun was set in a great shell of diamond?”

“What are you saying about the sun?” the priest asked, frowning.

“Nothing,” Chimal said. Something, he thought to himself, something that I dare not say aloud or I will soon be as dead as Popoca who first saw the ray. I have seen it too, and it was just like the sun shining on water or on diamond. Why had the priests not told them of the thing in the sky that made that flash of light? He broke off these thoughts as the priests carried in the sacred volumes.

The books were bound with human skin and were ancient and revered: on festival days the priests read parts from them. Now they placed them on the stone ledge and withdrew. Citlallatonac pushed at them, holding first one up to the light, then the other.

“You want to read the second book of Tezcatlipoca,” Chimal said. “And what I speak about is on the thirteenth or fourteenth page.”

A book dropped with a sharp noise and the priest turned wide eyes upon Chimal. “How do you know that?”

“Because I have been told and I remember. That is what was said aloud, and I remember the page number being spoken.”

“You can read, that is how you know this. You have come secretly to the temple to read the forbidden books…”

“Don’t be silly, old man. I have never been to this temple before. I remember, that is all.” Some demon goaded Chimal on in the face of the priest’s astonishment “And I can read, if you must know. That is not forbidden either. In the temple school I learned my numbers, as did all the other children, and I learned to write my name, just as they did. When the others were taught the writing of their names I listened and learned as well and therefore know the sounds of all the letters. It was really very simple.”

The priest was beyond words and did not answer. Instead he groped through the tumbled books until he found the one Chimal had named, then turned the pages slowly, shaping the words aloud as he read. He read, turned back the page and read again – then dropped the book.

“You see I am correct,” Chimal told him. “I shall marry, soon, to one of my own choosing after I have consulted long and well with the matchmaker and the clan leader. That is the way to do it by law…”

“Do not tell me the law, small man! I am the first priest and I am the law and you will obey me.”

“We all obey, great Citlallatonac,” Chimal answered quietly. “None of us are above the law and all of us have our duties.”

“Do you mean me? Do you dare to mention the duties of a priest, you a… nothing? I can kill you.”

“Why? I have done nothing wrong.”

The priest was on his feet, screeching in anger now, looking up into Chimal’s face and spattering him with saliva as the words burst from his lips.

“You argue with me, you pretend to know the law better than I do, you read though you were never taught to read. You are possessed by one of the black gods and I know it, and I shall release that god from inside your head.”

Angry himself, but coldly angry, Chimal could not keep a grimace of distaste from his mouth. “Is that all you know, priest? Kill a man who disagrees with you – even though he is right and you are wrong? What kind of a priest does that make of you?”

With a wordless scream the priest raised both his fists and brought them down together to strike Chimal and tear the voice from his mouth. Chimal seized the old man’s wrists and held them easily even though the priest struggled to free himself. There was a rush of feet as the horrified onlookers ran to help the first priest. As soon as they touched him, Chimal released his hands and stepped back, smiling crookedly.

Then it happened. The old man raised his arms again, opened his mouth wide until his almost gumless jaws were pinkly visible – then cried out, but no words came forth.

There was a screech, more of pain than anger now, and the priest crashed to the floor like a felled tree. His head struck the stone with a hollow thudding sound and he lay motionless, his eyes partly open and the yellowed whites showing, while a bubble of froth foamed on his lips.

The other priests rushed to his side, picked him up and carried him away, and Chimal was struck down from behind by one of them who carried a club. If it had been another weapon it would have killed him, and even though Chimal was unconscious this did not stop the priests from kicking his inert body before they carried him away too.

As the sun cleared the mountains it shone through the openings in the wall and struck fire from the jewels in Coatlicue’s serpent’s eyes. The books of the law lay, neglected, where they had been dropped.

7

“It looks like old Citlallatonac is very sick,” the priest said in a low voice while he checked the barred entrance to Chimal’s cell. It was sealed by heavy bars of wood, each thicker than a man’s leg, that were seated into holes in the stone of the doorframe. They were kept in place by a heavier, notched log that was pegged to the wall beyond the prisoner’s reach: it could only be opened from the outside. Not that Chimal was free to even attempt this, since his wrists and ankles were tied together with unbreakable maguey fibre.

“You made him sick,” the young priest added, rattling the heavy bars. He and Chimal were of the same age and had been in the temple school together. “I don’t know why you did it. You were in trouble in school, but I guess we all were, more or less, that is the way boys are. I never thought that you would end up doing this.” Almost as a conversational punctuation mark he jabbed his spear between the bars and into Chimal’s side. Chimal rolled away as the obsidian point dug into the muscle of his side and blood ran from the wound.

The priest left and Chimal was alone again. There was a narrow slit in the stone wall, high up, that let in a dusty beam of sunlight. Voices penetrated too, excited shouts and an occasional wail of fear from some woman.

They came, one after another, everyone, as word spread through the villages. From Zaachila they ran through the fields, tumbling like ants from a disturbed nest, to the riverbed and across the sand. On the other side they met the people from Quilapa, running, all of them, in fear. They grouped around the base of the pyramid in a solid mass, shouting and calling to one another for any bits of news that might be known. The noise died only when a priest appeared from the temple above and walked slowly down the steps, his hands raised for silence. He stopped when he reached the sacrificial stone. His name was Itzcoatl and he was in charge of the temple school. He was a stern, tall man in his middle years, with matted blond hair that fell below his shoulders. Most people thought that some day he would be first priest.

“Citlallatonac is ill,” he called out, and a low moan was breathed by the listening crowd. “He is resting now and we attend him. He breathes but he is not awake.”

“What is the illness that struck him down so quickly?” one of the clan leaders called out from below.

Itzcoatl was slow in answering; his black-rimmed fingernail picked at a dried spot of blood on his robe. “It was a man who fought with him,” he finally said. Silence stifled the crowd. “We have the man locked away so we may question him later, then kill him. He is mad or he is possessed by a demon. We will find out. He did not strike Citlallatonac but it is possible that he put a curse on him. The name of this man is Chimal.”

The people stirred and hummed like disturbed bees at this news, and drew apart. They were still closely packed, even more so now as they moved away from Quiauh, as though her touch might be poisonous. Chimal’s mother stood in the center of the open space with her head lowered and her hands clasped before her, a small and lonely figure.

This was the way the day went. The sun mounted higher and the people remained, waiting. Quiauh stayed as well, but she moved off to one side of the crowd where she would be alone: no one spoke to her or even looked her way. Some people sat on the ground or talked in low voices, others went into the fields to relieve themselves but they always returned. The villages were deserted and, one by one, the cooking fires went out. When the wind was right the dogs, who had not been watered or fed, could be heard barking, but no one paid attention to them.

By evening it was reported that the first priest had regained consciousness, but was still troubled. He could move neither his right hand nor his right leg and he had trouble speaking. The tension in the crowd grew perceptibly as the sun reddened and sank behind the hills, ( Once it had dropped from sight the people of Zaachila hurried, reluctantly, back to their village. They had to be across the river by dark – for this was the time when Coatlicue walked. They would not know what was happening at the temple, but at least they would be sleeping on their own mats this night. For the villagers of Quilapa a long night stretched ahead. They brought bundles of straw and cornstalks and made torches. Though the babies were nursed no one else ate, nor, in their terror, were they hungry.

The crackling torches held back the darkness of the night and some people laid their heads on their knees and dozed, but very few. Most just sat and watched the temple and waited. The praying voices of the priests came dimly down to them and the constant beating of the drums shook the air like the heartbeat of the temple.

Citlallatonac did not get better that night, but he did not get worse either. He would live and say the morning prayers, and then, during the coming day, the priests would meet in solemn assembly and a new first priest would be elected and the rituals performed that established him in that office. Everything would be all right. Everything had to be all right.

There was a stirring among the watchers when the morning star rose. This was the planet that heralded the dawn and the signal for the priests to once more beg Huitzilopochtli, the Hummingbird Wizard, to come to their aid. He was the only one who could successfully fight the powers of darkness, and ever since he had brought the Aztec people into being he had watched over them. Each night they called to him with prayers and he went forth with his thunderbolts and fought the night and the stars and defeated them so that they retreated and the sun could rise again.

Huitzilopochtli had always come to the aid of his people, though he had to be induced with sacrifices and the proper prayers. Had not the sun risen every day to prove it? Proper prayers, that was the important thing, proper prayers.

Only the first priest could speak these prayers. The thought was unspeakable yet it had been there all the night. The fear was still there like a heavy presence when priests with smoking torches emerged from the temple to light the way for the first priest. He came out slowly, half carried by two of the younger priests. He stumbled with his left leg, but his right leg only dragged limply behind him. They took him to the altar and held him up while the sacrifices were performed. Three turkeys and a dog were sacrificed this time because much help was needed. One by one the hearts were torn out and placed carefully in Citlallatonac’s clasping left hand. His fingers clamped down tight until blood ran from between his fingers and dripped to the stone, but his head hung at a strange angle and his mouth drooped open.

It was time for the prayer.

The drums and the chanting stopped and the silence was absolute. Citlallatonac opened his mouth and the cords in his neck stood out tautly as he struggled to speak. Instead of words he emitted only a harsh croaking sound and a long dollop of saliva hung down, longer and longer, from his drooping lip.

He struggled even harder then, writhing against the hands that held him up, trying to force words through his useless throat, until his face flushed with the effort. He tried too hard, because, suddenly, he jerked in pain, as though he were a loose-limbed doll being tossed into the air, then slumped limply.

After this he did not stir again and Itzcoatl ran over and placed his ear to the old man’s chest.

“The first priest is dead,” he said, and everyone heard these terrible words.

A wail of agony rose up from the assembled mob, and across the river in Zaachila they heard it and knew what it meant. The women clutched their children to them and whimpered, and the men were just as afraid.

At the temple they watched, hoping where there was no hope, looking at the morning star that rose higher in the sky with every passing minute. Soon it was high, higher than they had ever seen it before, because on every other day it had been lost in the light of the rising sun.

Yet on this day there was no glow on’ the eastern horizon. There was just the all-enveloping darkness.

The sun was not going to rise.

This time the cry that went up from the crowd was not pain but fear. Fear of the gods and the unending battle of the gods that might swallow up the whole world. Might not the powers of the night now triumph in the darkness so that this night would go on forever? Would the new first priest be able to speak powerful enough prayers to bring back the sun and the daylight that is life?

They screamed and ran. Some of the torches went out and in the darkness panic ruled. People fell and were trampled and no one cared. This could be the end of the world.

Deep under the pyramid Chimal was awakened from uncomfortable sleep by the shouting and the sound of running feet. He could not make out the words. Torchlight flickered and vanished outside the slit. He tried to roll over but found that he could barely move. At least his legs and arms were numb now. He had been bound for what felt like countless hours and at first the agony in his wrists and ankles had been almost unbearable. But then the numbness had come and he could no longer feel if these limbs were even there. All day and all night he had lain there, bound this way, and he was very thirsty. And he had soiled himself, just like a baby; there was nothing else he could do. What was happening outside? He suddenly felt a great weariness and wished that it was all over and that he was safely dead. Small boys do not argue with priests. Neither do men.

There was a movement outside as someone came down the steps, without a light and feeling the wall for guidance. Footsteps up to his cell, and the sound of hands rattling at the bars.

“Who is there?” he cried out, unable to bear the unseen presence in the darkness. His voice was cracked and hoarse. “You’ve come to kill me at last, haven’t you? Why don’t you say so?”

There was only the sound of breathing – and the rattle of the locking pin being withdrawn. Then, one by one the heavy bars were drawn from the socket and he knew that someone had entered the cell, was standing near him.

“Who is it?” he shouted, trying to sit up against the wall.

“Chimal,” his mother’s voice said quietly from the darkness.

At first he did not believe it, and he spoke her name. She knelt by him and he felt her fingers on his face.

“What happened?” he asked her. “What are you doing here – and where are the priests?”

“Citlallatonac is dead. He did not say the prayers and the sun will not rise. The people are mad and howl like dogs and run.”

I can believe that, he thought, and for a few moments the same panic touched him, until he remembered that one end is the same as another to a man who is about to die. While he wandered through the seven underworlds it would not matter what happened on the world above.

“You should not have come,” he told her, but there was kindness in the words and he felt closer to her than he had for years. “Leave now before the priests find you and use you for a sacrifice as well. Many hearts will be given to Huitzilopochtli if he is to fight a winning battle against the night and stars now when they are so strong.”

“I must free you,” Quiauh said, feeling for his bindings. “What has happened is my doing, not yours, and you are not the one who should suffer for it”

“It’s my fault, true enough. I was fool enough to argue with the old man and he grew excited and then suddenly sick. They are right to blame me.”

“No,” she said, touching the wrappings on his wrists, then bending over them because she had no knife. “I am to blame because I sinned twenty-two years ago and the punishment should be mine.” She began to chew at the tough fibers.

“What do you mean?” Her words made no sense.

Quiauh stopped for a moment and sat up in the darkness and folded her hands in her lap. What must be said had to be said in the right way.

“I am your mother, but your father is not the man you thought. You are the son of Chimal-popoca who was from the village of Zaachila. He came to me and I liked him very much, so I did not refuse him even though I knew it was very wrong. It was night time when he tried to cross back over the river and he was taken by Coatlicue. All of the years since I have waited for her to come and take me as well, but she has not. Hers is a larger vengeance. She wishes to take you in my place.”

“I can’t believe it,” he said, but there was no answer because she was chewing at his bindings again. They parted, strand by strand, until his hands were freed. Quiauh sought the wrappings on his ankles. “Not those, not yet,” he gasped as the pain struck his reviving flesh. “Rub my hands. I cannot move them and they hurt.”

She took his hands in hers and massaged them softly, yet each touch was like fire.

“Everything in the world seems to be changing,” he said, almost sadly. “Perhaps the rules should not be broken. My father died, and you have lived with death ever since. I have seen the flesh that the vultures feed upon and the fire in the sky, and now the night that never ends. Leave me before they find you. There is no place I can escape to.”

“You must escape,” she said, hearing only the words she wanted as she worked on the bindings of his ankles. To please her, and for the pleasure of feeling his body free again he did not stop her.

“We will go now,” she said when he was able to stand on his feet at last. He leaned on her for support as they climbed the stairs, and it was like walking on live coals. There was only silence and darkness beyond the doorway. The stars were clear and sharp and the sun had not risen. Voices murmured above as the priests intoned the rites for the new first priest

“Good-bye, my son, I shall never see you again.”