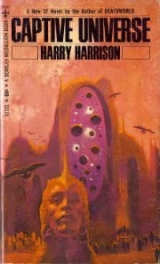

Текст книги "Captive Universe"

Автор книги: Harry Harrison

Соавторы: Harry Harrison

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

“I think I do.” She spoke in an almost inaudible voice. “But it is all so terrible. Why should they do a thing like that? Not obeying the will of the Great Designer.”

“Because they were wicked and selfish men, even if they were observers. And the observers now are no better. They are concealing the knowledge again. They will not permit me to reveal it. They have planned to send me away from here forever. Now – will you help me to right this wrong?”

Once more the girl was far beyond her depth, floundering in concepts and responsibilities she was not equipped to handle. In her ordered life there was only obedience, never decision. She could not force herself to conclusions now. Perhaps the decision to run to him, to question him, had been the only act of free will she had ever accomplished in her entire lengthened, yet stunted, lifetime.

“I don’t know what to do? I don’t want to do anything. I don’t know …”

“I know,” he said, closing up his clothing and wiping his fingers on the cloth. He reached out and took her chin in his hand and turned her great empty eyes to him. “The Master Observer is the one who must decide, since that is his function in life. He will tell you whether I am right or wrong and what is to be done. Let us go to the Master Observer.”

“Yes, let us go.” She almost sighed with relief with the removal of the burden of responsibility. Her world was ordered again and the one whose appointed place in life was to decide, would decide. Already she was forgetting the confused events of the past days: they just did not fit into her regularized existence.

Chimal huddled low in the car so his soiled clothing would not be seen, but the effort was hardly necessary. There were no casual walkers in the tunnels. Everyone must be manning the important stations – or was physically unable to help. This hidden world was in as much of storm of change as the valley outside. With more change on the way, hopefully, Chimal thought as he eased himself from the car at the tunnel entrance nearest to the Master Observer’s quarters. The halls were empty.

The observer’s quarters were empty too. Chimal went in, searched them, then dropped full length onto the bed.

“Hell be back soon. The best thing we can do is to wait here for him.” There was little else, physically, that he could do at this time. The pain drugs made him sleepy and he dared not take any more of them. Watchman Steel sat in a chair, her hands folded on her lap, waiting patiently for the word of instruction that would strip away her problems. Chimal dozed, and woke with a start, then dozed again. The bedding and the warmth of the room dried his clothing and the worst of the pain ebbed away. His eyes closed and, in spite of himself, he slept.

The hand on his shoulder pulled him from the deep pit of sleep that he did not want to leave. Only when memory returned did he fight against it and force his eyelids open.

“There are voices outside,” the girl said. “He is coming back. It is not seemly to be found here, lying like this.”

Not seemly. Not safe. He would not be gassed and taken again. Yet it took every bit of will and energy he had remaining to pull himself erect, to stand, to lean on the girl and direct her to the far side of the room.

“We’ll wait here in silence,” he said, as the door opened.

“Do not call me until the machine is up, then,” the Master Observer said. “I am tired and these days have taken years from my life. I must rest. Maintain the fog in the northern end of the valley in case someone might see. When the derrick is rigged one of you will ride it down to attach the cables. Do that yourselves. I must rest.”

He closed the door and Chimal reached out and put both hands over his mouth.

7

The old man did not struggle. His hands fluttered limply for a moment and he rolled his eyes upward to look into Chimal’s face, but otherwise he made no protest. Though he swayed with the effort, Chimal held the Master Observer until he was sure the men outside had gone, then released him and pointed to a chair.

“Sit,” he commanded. “We shall all sit down because I can no longer stand.” He dropped heavily into the nearest chair and the other two, almost docilely, obeyed his order. The girl was waiting for instruction: the old man was almost destroyed by the events of the preceding days.

“Look at what you have done,” the Master Observer said hoarsely. “At the evils committed, the damage, the deaths. Now what greater evil do you plan…”

“Hush,” Chimal said, touching his finger to his lips. He felt drained of everything vital, even of hatred at this moment, and his calmness quieted the others. The Master Observer mumbled into silence. He had not used his depilatory cream so there was gray stubble on his cheeks, as well as pockets of darkness under his eyes.

“Listen carefully and understand,” Chimal began, in a voice so quiet that they had to strain to hear. “Everything has changed. The valley will never be the same again, you have to realize that. The Aztecs have seen me, mounted upon a goddess, have found out that everything is not as they always thought it was. Coatlicue may never walk again to enforce the taboo. Children will be born of parents of different villages, they will be Arrivers – but will not have an arrival. And your people here, what of them? They know that something is terribly wrong, yet they do not know what. You must tell them. You must do the only thing possible, and that is to turn the ship.”

“Never!” Anger pulled the old man upright, and the eskoskeleton helped his gnarled fingers to curl into fists. “The decision has been made and it cannot be changed.”

“What decision is that?”

“The planets of Proxima Centauri were unsuitable. I told you that. It is too late to return. We go on.”

“Then we have passed Proxima Centauri… ?”

The Master Observer opened his mouth– – then clamped it shut again as he realized the trap he had fallen into. Fatigue had betrayed him. He glared at Chimal, then at the girl.

“Go on,” Chimal told him. “Finish what you were going to say. That you and other observers have worked against the Great Designer’s plan and have turned us from our orbit. Tell this girl so she may tell the others.”

“This is none of your affair,” the old man snapped at her. “Leave and do not discuss what you have heard here.”

“Stay,” Chimal said, pressing her back into her seat as she half rose at the order. “There is more truth to come. And perhaps after a while the observer will realize that he wants you here where you cannot tell the others what you know. Then later he will think of a way to kill you or to send you off into space. He must keep his guilty secret because if he is found out he is destroyed. Turn the ship, old man, and do one good thing with your life.”

Surprise was gone and the Master Observer had control of himself again. He touched his deus and bowed his head. “I have finally understood what you are. You are to evil as the Great Designer is to good. You have come to destroy and you shall not succeed. What you are…”

“Not good enough,” Chimal broke in. “It is too late to call names or settle this by insult. I give you facts, and I ask you to dare deny them. Watch him closely, Steel, and listen to his answers. I give you first the statement that we are no longer on the way to Proxima Centauri. Is that fact?”

The old man closed his eyes and did not answer, then crouched in his chair in fear as Chimal sprang to his feet. But Chimal went by him and pulled the red-bound log from the rack and let it fall open. “Here is the fact, the decision that you and the others made. Shall I let the girl read it?”

“I do not deny it. This was a wise decision made for the good of all. The watchman will understand. She, and all the others will obey, whether they are told or not.”

“Yes, you’re probably right,” Chimal said, wearily, hurling the book aside and dropping back into his chair. “And that is the biggest crime of all. No not yours, His. The most evil one, the one you call the Great Designer ”

“Blasphemy,” the Master Observer croaked, and even Watchman Steel shrank back from the awfulness of Chimal’s words.

“No, just truth. The books told me that there are things called nations on Earth. They seem to be large groups of people, though not all of the people on Earth. It is hard to tell exactly why these nations exist or what their purpose is, but that is not important. What is important is that one of these nations was led by the man we now call the Great Designer. You can read his name, the name of the country, they are meaningless to us. His power was so great he built a memorial to himself greater than any ever constructed before. In his writings he says how the thing he does is greater than the pyramids or anything that came before. He says that pyramids are great structures, but that his structure is greater – an entire world. This world. In detail he writes how it was designed and made and sent on its way and he is very proud of it. Yet what he is really proud of is the people who live in this world, who will go out to the stars and carry human life in his name. Don’t you see why he feels that way? He has created an entire race to worship his image. He has made himself God.”

“He is God,” the Master Observer said, and Watchman Steel nodded agreement and touched her deus.

“Not God, or even a black god of evil, though he deserves that name. Just a man. A frightful man. The books talk of the wonders of the Aztecs he created to carry out his mission, their artificially induced weakness of mind and docility. This is no wonder – but a crime. Children were born, from the finest people in the land, and they were stunted before birth. They were taught superstitious nonsense and bundled off into this prison of rock to die without hope. And, even worse, to raise their children in their own imbecilic image for generation after generation of blunted, wasted lives. You know that, don’t you?”

“It was His will,” the old man answered, untroubled.

“Yes it was, and it doesn’t bother you at all because you are the leader of the jailers who imprison this race, and you wish to continue the imprisonment forever. Poor fool. Did you ever think where you and your people came from? Is it chance that you are all so faithful to your trust and so willing to serve? Don’t you realize that you were made in the same way the Aztecs were made? That after finding the ancient Aztecs as a model society for the valley dwellers, this monster looked for a group to do the necessary housekeeping for the centuries-long voyage. He found it in the mysticism and monasticism that has always been a nasty side path taken by the human race. Hermits wallowing in filth in caves, others staring into the sun for a lifetime of holy blindness, orders that withdrew from the world and sealed themselves away for lives of sacred misery. Faith replacing thinking and ritual replacing intelligence. This man examined all the cults and took the worst he could find to build the life you lead. You worship pain, and hate love and natural motherhood. You are smug with the years of your long lives and look down upon the short-lived Aztecs as lower animals. Don’t you realize the ritualized waste of your empty lives? Don’t you understand that your intelligence has also been dimmed and diminished so that none of you will question the things you have to do? Can you not see that you are just as much condemned prisoners as the people in the valley?”

Exhausted, Chimal dropped back in his chair, looking from the cold face of hatred to the empty face of incomprehension. No, they had no idea what he was talking about. There was no one, in the valley or out, whom he could talk to, communicate with, and a cold loneliness settled on him.

“No, you cannot see,” he said, with weary resignation. “The Great Designer has designed too well.”

At his words their fingers automatically went to their deuses and he was too tired to do more than sigh.

“Watchman Steel,” he ordered, “there is food and drink over there. Bring them to me.” She hurried to his bidding. He ate slowly, washing the food down with the still-warm tea from the Thermos, while he planned what to do next.

The Master Observer’s hand crept to the communicator at his waist and Chimal had to reach out and pull it from his belt. “Yours too,” he told Watchman Steel, and did not bother to explain why he wanted it. She would obey in either case. He could expect no more help from anyone. From now on he was alone.

“There is none higher than you, is there, Master Observer?” he asked.

“All know that, except you.”

“I know it too, you must realize that. And when the decision was made to change the orbit, the observers agreed but the final decision was made by the then Master Observer. Therefore you are the one who must know all of the details of this world, where the spaceships are and how to activate them, the navigation and how it is done, and the schools and all the arrangements for the Day of Arrival, everything.”

“Why do you ask me these things?”

“I’ll make my meaning clear. There are many responsibilities here, far too many to be passed on by word of mouth from one Master Observer to the other. So there are charts that show all the tunnels and chambers and their contents, and there are breviaries for the schools and the spaceship. Why there must even be a breviary for that wonderful day of arrival when the valley is open. – where is it?”

The last words were a demanding question and the old man started and his eyes jumped to the wall, then instantly away. Chimal turned to look up at the red-lacquered cabinet that hung there, in front of which a light always burned. He had noticed it before but never thought consciously about it.

When he rose to go to it the Master Observer attacked him, his aged hands and the rods of his eskoskeleton striking Chimal about the head and shoulders. Finally, he had understood what Chimal had in mind. The struggle was brief. Chimal prisoned the old man’s hands, clasping them together behind his back. Then he remembered the failure of his own eskoskeleton and threw the power switch on the Master Observer’s harness. The motors died and the joints locked, holding the man captive. Chimal picked him up gently and laid him on his side on the bed.

“Watchman Steel, duty,” the old man ordered, though his voice quavered. “Stop him. Kill him. I order you to do this.”

Unable to understand more than a fraction of what had occurred the girl stood, wavering helplessly between them.

“Don’t worry,” Chimal told her. “Everything will be all right.” Against her slight resistance he forced her back into the chair and disconnected her eskoskeleton too, tearing the power pack free. He tied her wrists together as well, with a cloth from the ablutory.

Only when they were both secured did he go to the cabinet on the wall and tug at its doors. They were locked. In a sudden temper he tore at it, pulling it bodily from the wall, ignoring the things the Master Observer was calling at him. The lock on the cabinet was more decorative than practical and the whole thing fell to pieces easily when he put it on the floor and stamped on it. He bent and picked a red-bound and gold decorated book from the wreckage.

“The Day of Arrival,” he read, then opened it. “That day is now.”

The basic instructions were simple enough, as were the instructions in all the breviaries. The machines would do the work, they had only to be activated. Chimal went over in his mind the course he would take, and hoped that he could walk that far. Pain and fatigue were closing in again and he could not fail now. The old man and the girl were both silent, too horrified by what he was doing to react. But this could change as soon as he left. He needed time. There were more cloths in the ablutory and he took them and sealed their mouths with them. If someone should pass they would not be able to give the alarm. He threw the communicators to the ground and broke them as well. He would not be stopped.

As he put his hand on the door he turned to face the wide, accusing eyes of the girl. “I’m right,” he told her. “You’ll see. There is much happiness ahead.” Taking the breviary for the Day of Arrival, he opened the door and left.

The caverns were still almost empty of people which was good: he did not have the strength to make any detours. Halfway to his goal he passed two watchmen, both girls, coming off duty, but they only stared with frightened empty eyes as he passed. He was almost to the entrance to the hall when he heard shouting and looked back to see the red patch of an observer hurrying after him. Was this chance – or had the man been warned? In either case, all he could do was go on. It was a nightmare chase, something out of a dream. The watchman walked at the highest speed his eskoskeleton would allow, coming steadily on. Chimal was unrestricted, but wounded and exhausted. He ran ahead, slowed, hobbled on, while the observer, shouting hoarse threats, ground in pursuit like some obscene mixture of man and machine. Then the door to the great chamber was ahead and Chimal pushed through it and closed it behind him, leaning his weight against it. His pursuer slammed into the other side.

There was no lock, but Chimal’s weight kept the door closed against the other’s hammering while he fought to catch his breath. When he opened the breviary his blood ran down the whiteness of the page. He looked at the diagram and the instructions again, then around the immensity of the painted chamber.

To his left was the wall of great boulders and massive rocks, the other side of the barrier that sealed the end of his valley. Far off to his right were the great portals. And halfway down this wall was the spot he must find.

He started toward it. Behind him the door burst open and the observer fell through, but Chimal did not look back. The man was down on his hands and knees and motors hummed as he struggled to rise. Chimal looked up at the paintings and found the correct one easily enough. Here was a man who stood out from the painted crowd of marchers, who stood away from them, bigger than them. Perhaps it was an image of the Great Designer himself: undoubtedly it was. Chimal looked into the depths of those nobly painted eyes and, if his mouth had not been so dry, he would have spat into the wide-browed perfection of the face. Instead he leaned forward, his hand making a red smear along the wall, until his fingers touched those of the painted image.

Something clicked sharply and a panel fell open, and there was a single large switch inside. Then the observer was upon Chimal as he clutched at it, and they fell together.

Their combined weight pulled it down.

8

Atototl was an old man, and perhaps because of this the priests in the temple considered him expendable. Then again, since he was the cacique of Quilapa, he was a man of standing and people would listen when he brought back a report. And he could be expected to obey. But, whatever their reasons, they had commanded him to go forth and he had bowed his head in submission and done as they had ordered.

The storm had passed and even the fog had lifted. Were it not for the black memories of earlier events it could have been the late afternoon of almost any day. A day after a rain, of course, the ground was still damp underfoot and off to his right he could hear the water in the river, rushing high against the banks as it drained the sodden fields. The sun shone warmly and brought little curls of mist from the ground. Atototl came to the edge of the swamp and squatted on his heels and rested. Was the swamp bigger than when he had seen it last? It seemed to be, but surely it would have to be larger after all that ram. But it would get lower again, it always had before. This was nothing to be concerned about, yet he must remember to tell the priests about it.

What a frightening place the world had become. He would almost prefer to leave it and wander through the underworlds of death. First there had been the death of the first priest and the day that was a night. Then Chimal had gone, taken by Coatlicue the priests had said, and it certainly had seemed right It must have been that way, but even Coatlicue had not been able to keep that spirit captive. It had returned with Coatlicue herself, riding her great back, garbed in blood and hideous, yet still bearing the face of Chimal. What could it all mean? And then the storm. It was all beyond him. A green blade of new grass grew at his feet and he reached down and broke it off, then chewed on it. He would have to go back soon to the priests and tell them what he had seen. The swamp was bigger, he must not forget that, and there was certainly no sign of Coatlicue.

He stood up and stretched his tired leg muscles, and as he did so he felt a distant rumbling. What was happening now? In terror he clutched his arms about himself, unable to run away while he stared at the waves that trembled the surface of the water before him. There was another rumble, louder this time, that he could feel in his feet, as though the entire world were shaking beneath him.

Then, with cracklings and grumblings the entire barrier of stone that sealed the mouth of the valley began to stir and slide. One great boulder moved downward, then another and another. Sinking into the solid ground, faster and faster, all of them moving, rushing down, crumbling and cracking and grinding together until they vanished from sight below. Then, as the valley opened up, the waters before him began to recede, rushing after the rock barrier, trickling and bubbling away in a thousand small cataracts, hurrying after the dam that had held it so long. Quickly the water ran, until a brown waste of mud, silvered with the flapping bodies of fish, stretched out where there had only been ponds and swamp just minutes before. Reaching out to the cliffs that were no longer a barrier but an exit from the valley, that framed something golden and glorious, filled with light and marching figures – Atototl spread his arms wide before the wonder of it all.

“It is the day of deliverance,” he said, no longer afraid. “And all the strange things came before it. We are free. We shall leave the valley at last.”

Hesitantly, he put one foot forward onto the still soft mud.

The booming of explosions was deafening inside the hall. As they started the observer fell away and cowered in panic on the floor. Chimal held to the great switch for support as the floor shook and the boulders stirred. This was the reason for the location of the carved reservoir below. Everything had been planned. The barrier that sealed the valley must stand on the stone just above the hollowed-out chamber. Now supports were being blown away and the rock weakened. The entire roof was falling away. With a final roar the last boulders tumbled downward, filling the reservoir below with their tops making a broken roadway out of the valley. Sunlight streamed in through the opening and fell upon the paintings for the first time.

Outside Chimal could see the valley with the mountains beyond and he knew that this time he had not failed.

This action was irreversible, the barrier was gone.

His people were free.

“Get up,” he said to the observer who was groveling against the wall. He pushed at him with his toe. “Get up and look and try to understand. Your people are free too.”