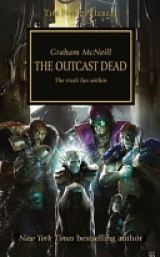

Текст книги "The Outcast Dead"

Автор книги: Грэм Макнилл

Жанр:

Боевая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

‘Isstvan V,’ said Sarashina.

Athena nodded. ‘No sooner had the sun gone black than the statue of Prometheus pulled against the chains holding it fast to the rock. The falcon took to the air as the metal links shattered, and a spear of fire appeared in the giant’s fist. The statue surged forward and cast the spear into the heart of the black sun, and the tip punched into its heart in a shower of blazing sparks.’

‘That bodes well for Lord Dorn’s fleet,’ noted Sarashina.

‘I’m not finished yet,’ said Athena.

She took a deep breath before continuing. ‘Even as the statue slew the sun with its spear cast, I saw it had left much of its inner substance behind. Chunks of obsidian remained stuck to the rock, and I knew the giant had struck prematurely, without his full weight behind the blow. Then the statue sank beneath the sand, and the falcon flew back to the rock. It swallowed the chunks of obsidian and then took to the air with a caw of triumph.’

‘That is everything?’ asked Sarashina.

‘That’s everything,’ agreed Athena, tapping her dream records. ‘I checked my Oneirocriticaand it makes for uncomfortable reading.’

Sarashina extended her hands, nodding in agreement as her fingers danced over the raised words and letters.

‘Ferrus Manus always was impetuous,’ she said. ‘He races ahead of his brothers to Isstvan V to deliver the death blow to the rebels, while leaving much of his force behind.’

‘Yes, but it’s the hawk with the amber eyes that concerns me,’ said Athena.

‘The importance of the falcon is paramount,’ agreed Sarashina. ‘Its obvious implication is troubling. What elements Ferrus Manus leaves behind will be devoured. What other interpretation do you give the falcon?’

‘It’s a symbol of war and victory in most cultures.’

‘Which, in itself, is not troublesome, so what gives you cause for concern?’

‘This,’ said Athena, opening her oldest Oneirocriticawith her manipulator arm and turning it around. As Sarashina’s fingers slipped easily over the pages, her serene expression turned to a frown as the words imprinted on the pages went on.

‘This is ancient belief,’ said Sarashina.

‘I know. Many of the gods worshipped by these extinct cultures displayed hawks as symbols of their battle prowess, which just confirms the more obvious symbolism. But I remembered the text of a rubbing taken from a marble sculpture uncovered by the Conservatory only a year ago in the rubble of that hive that collapsed in Nordafrik.’

‘Kairos,’ said Sarashina with a shudder. ‘I felt its fall. Six million souls buried under the sands. Terrible.’

Athena had been aboard Lemurya, one of the great orbital plates circling Terra, when Kairos hive sank into the desert, but she had felt the aetheric aftershock of its doom like a tidal wave of fear and pain. An empathic shudder of grief pulsed from Sarashina’s aura.

‘The hive’s fall exposed a series of tomb-complexes further west, and among the mortuary carvings were hawks. It’s said that the Gyptians considered the hawk to be a perfect symbol of victory, though they viewed it as a struggle between opposing elemental forces, especially the spiritual over the corrupt, as opposed to physical victory.’

‘And how does that fit within your precept?’ asked Sarashina.

‘I’m getting to that,’ said Athena, pushing a sheet of paper towards her. ‘This is the text of a scroll I copied a few years ago from a deteriorating data-coil recovered from the ruins of Neoalexandria. It’s just a list, a pantheon of old gods, but one name in particular stuck out. Taken together with the amber eyes and the colouring of the hawk’s plumage…’

‘Horus,’ said Sarashina as her finger stopped halfway down the list.

‘Could the hawk with the amber eyes represent the Warmaster and his rebels?’

‘Pass this to the Conduit,’ said Sarashina. ‘Now!’

‘PLEASE,’ SAID PALLADIS. ‘Don’t hurt these people, they have already been through enough.’

Ghota took a step into the temple, his heavy, hobnailed boots sounding like gunshots as he crushed glass and rock beneath them. He swept his gaze around the terrified throng, finally settling on Roxanne. He smiled, and Palladis saw his teeth were steel fangs, triangular like a shark’s.

Ghota pointed at Roxanne. ‘Don’t care about others,’ he said. ‘Just want her.’

The man’s voice was impossibly deep, as though dragged unwillingly from some gravelled canyon in his gut. It sounded like grinding rocks, flat and curiously not echoing from the stone walls of the temple.

‘Look, I know there was some blood spilled, but your men attacked Roxanne,’ said Palladis. ‘She had every right to defend herself.’

Ghota’s head cocked to one side, as though this argument had never been put to him before. It amused him, and he laughed, or at least Palladis guessed that the sound of a mountain avalanche coming from his mouth was laughter.

‘She was trespassing,’ growled Ghota. ‘She needed to pay a toll, but she decided it didn’t apply to her. My men were enforcing the Babu’s law. She broke the law, now she has to pay. It’s simple. Either she comes with me or I kill everyone in here.’

Palladis fought down his rising tension. All it would take would be one person to panic, and this temple would become a charnel house. Maya sheltered her two boys, while Estaben had his eyes closed and muttered something inaudible with his hands clasped before him. Roxanne sat with her head bowed, and Palladis felt her fear hit him like a blow.

So easy to forget how different she is…

He took a step towards Ghota, but the man raised his hand and shook his head.

‘You’re fine where you are,’ said Ghota, ‘but I can see you’re hesitating, trying to think if there’s some way you can talk your way out of this. You can’t. You’re also thinking if there’s any way the boksigirl can do what she did to the men she killed. She might be able to kill a couple of them, but it won’t work on me. And if she tries it I’ll make sure she doesn’t die for weeks. I know exactlyhow fragile the human body is, and I promise you that she’ll suffer. Agonisingly. You know me, and you know I mean what I say.’

‘Yes, Ghota,’ said Palladis. ‘I know you, and trust me, I believe every word you say.’

‘Then hand her over, and we’ll be gone.’

Palladis sighed. ‘I can’t do that.’

‘You know what she is?’

‘I do.’

‘Stupid,’ said Ghota, drawing his heavy pistol with such swiftness that Palladis wasn’t sure what he’d seen until the deafening bang filled the chamber with noise. Everyone screamed, and went on screaming as they saw what the gunshot had done to Estaben.

It had destroyed him. Literallydestroyed him.

The impact pulped his upper body, hurling it across the chamber and breaking it apart over the chest of the Vacant Angel. Ribbons of shredded meat drooled from the statue’s praying hands and sticky brain matter and fragments of skull decorated its featureless face.

Maya screamed and Roxanne threw herself to the floor. Weeping mourners huddled together in the pews, convinced they were soon to join their loved ones. Children screamed in fear and mothers let them cry. Roxanne looked up at Palladis and reached for the hem of her hood, but he shook his head.

Ghota flexed his wrist, and Palladis found himself looking down the enormous barrel of a weapon that could obliterate him. Coils of muzzle smoke drifted from the gun, and Palladis could smell the chemical reek of high-grade propellant. The dim light of the temple reflected from an eagle stamped on the pistol’s barrel.

‘You are next,’ said Ghota. ‘You’ll die and we’ll take the girl anyway.’

Palladis felt his body temperature drop suddenly, as though a nearby meat locker had just opened and gusted a breath of arctic air into the chamber. The hairs on his arms stood erect, and he shivered as though someone had just walked over his grave. Sweat beaded on his brow and though every one of his senses was telling him the chamber was warm, his body was shivering like it had on the nights he’d spent on the open plains of Nakhdjevan.

The sounds of frightened people faded into the background, and Palladis heard the snorting, wheezing emphysemic breath of something wet and rotten. Colour drained from the world and even Ghota’s colourful tattoos seemed dull and prosaic. The cold air bloated the chamber, a sudden swelling of icy breath that seemed to swirl around every living thing and caress it with a repulsively paternal touch.

Palladis watched as one of Ghota’s thugs stiffened, clutching his chest as though a giant fist had reached inside his ribcage and squeezed his heart. The man turned the colour of week-old snow and he collapsed into a pew, gasping for breath as his face twisted in a rictus mask of pain and terror.

Another man fell as though poleaxed and without the drama of his comrade. His face was pulled tight in a grimace of horror, but his body remained unmarked. Ghota snarled and aimed his pistol at Roxanne, but before he could pull the trigger, another of his men shrieked in abject terror. So stark and primal was his scream that even an inhuman monster like Ghota was caught unawares.

Colour flooded back into the world, and Palladis threw himself to the side as Ghota’s pistol boomed with deafening thunder. Palladis didn’t see what he’d shot at, but heard a buzzing crackle as it hit something. More screaming sounded from the far end of the chamber, frantic, urgent and terrified. Palladis squirmed along the floor between the pews, knowing something terrible was happening, but with no idea what it was.

His breath misted before him, and he saw webs of frost forming on the back of the timber bench at his side. He flinched as Ghota fired again, roaring with an anger that was terrifying in its power. The sound of his rage went right through Palladis, penetrating to the marrow and leaving him sick and paralysed with terror.

No mortal warrior could vent such battle rage.

Pinned to the floor with terror, Palladis wrapped his hands over his head and tried to shut out the sounds of terrified screams. He kept his face pressed to the cold flagstones of the temple floor, taking icy air into his lungs with every terrified breath. The screaming seemed to go on without pause. Shrieks of terror and pain, overlaid with angry roars of thunderous defiance in a strange battle-cant that sounded like the fury of an ancient war god.

Palladis remained motionless until he felt a drop of cold water on the back of his neck. He looked up to see the frost on the back of the bench was melting. The freezing temperature had vanished as swiftly as it had arrived. He felt a hand touch his shoulder, and cried out, flailing his arms at his attacker.

‘Palladis, it’s me,’ said Roxanne. ‘It’s over, he’s gone.’

Palladis struggled to assimilate that information, but found it too unbelievable to process.

‘Gone?’ he said at last. ‘How? I mean, why?’

‘I don’t know,’ said Roxanne, peeking over the top of the bench.

‘Did you do it?’ asked Palladis, as a measure of his composure began to return. He pulled himself upright and risked a quick look over the top of the bench.

‘No,’ said Roxanne. ‘I swear I didn’t. Take a look. This isn’t anything I could have done.’

Roxanne wasn’t lying. Ghota was gone, leaving a greasy fear-stink in the air and a fug of acrid gunsmoke.

Seven bodies lay sprawled by the entrance to the temple: seven hard, dangerous men. Each one lay unmoving with their limbs twisted at unnatural angles, as though they had been picked up by a simpleminded giant and bent out of shape until they broke. Palladis had seen his share of abused corpses, and knew that every bone in their bodies was crushed.

‘What in Terra’s name just happened?’ said Palladis, moving to stand in the centre of the temple. ‘What killed these men?’

‘Damned if I know,’ said Roxanne, ‘but I’m not going to say I’m not grateful for whatever did it.’

‘I suppose,’ agreed Palladis, as heads began appearing over the tops of benches. Their fear turned to amazement as they saw Palladis standing amid the ruin of seven men. Palladis saw the awe in their faces and shook his head, holding his hands up to deny any part in their deaths.

‘This wasn’t me,’ he said. ‘I don’t know what happ…’

The words died in his throat as he looked back down the central passageway of the temple towards the Vacant Angel. The viscera that had been blown out of Estaben’s guts hung from the statue like grotesque festival decorations, and Maya wailed like a banshee at this latest agonising loss.

For a fleeing second, it was as though a pale nimbus of light played around the outline of the statue. Palladis felt the lingering presence of death, and was not surprised to see a leering, crimson-eyed skull swimming in the dark-veined marble of the statue’s face. It vanished so suddenly that Palladis couldn’t be sure he’d seen anything at all.

‘So you have come for me at last,’ he whispered under his breath.

Roxanne was at his side a moment later.

‘What did you say?’

‘Nothing,’ said Palladis, turning away from the statue.

‘I wanted to thank you,’ said Roxanne.

‘For what?’

‘For not letting them take me.’

‘You’re one of us,’ he said. ‘I’d no more let them take you than anyone else.’

He saw the disappointment in her eyes, and immediately regretted his thoughtless words, but it was too late to take them back now.

‘So what happened here?’ said Roxanne.

‘Death happened here,’ said Palladis, fighting the urge to look over his shoulder at the Vacant Angel. He lifted his voice so that the rest of his congregation could hear him. ‘Evil men came to us and paid the price for their wickedness. Death looks for any chance to take you to into his dark embrace, and to walk the path of evil is to bring you to his notice. Look now, and see the price of that path.’

The people of the temple cheered, holding one another tight as his words reached them. They had stepped from the shadow of death and the light beyond had never seemed brighter. The colours of the world were unbearably vivid, and the comfort of the loved one nearby had never been more achingly desirable. They looked at him as the source of their newfound joy, and he wanted to tell them that he had not caused these men to die, that he was as shocked as they were to still be alive.

But one look at their enraptured faces told him that no words he could summon would change their unshakable belief in him.

Roxanne gestured to the dead bodies. ‘So what do we do with them?’

‘Same as all the rest,’ he said. ‘We burn them.’

‘Ghota won’t take this lightly,’ said Roxanne. ‘We should get out of here. He’ll raze this place to the ground.’

‘No,’ said Palladis, picking up the strange rifle one of Ghota’s men had carried. ‘This is a temple of death, and when that bastard comes back, he’s going to find out exactly what that means.’

FIVE

Old Wounds

The Unthinkable

The Troubled Painter

KAI AND ATHENA descended the tower, making their way down the grav-lifts towards the mess facilities near the base of the tower. They hadn’t spoken since breaking their most recent connection to the nuncio, and both were drained with the effort of maintaining a shared dreamspace. An appraisal of his improvement could wait until they had the distraction of a drink and the barrier of a table between them.

The mess halls of the tower were iron-walled, stark and low-lit, reminding Kai of the serving facilities aboard a starship. He wondered if that was deliberate, given where most astropaths were destined to spend much of their lives. Solitary figures were scattered around the echoing chamber, lost in thought, trailing their fingers over an open book or adding fresh interpretive symbols to their Oneirocritica. They found a table and sat in silence for a moment.

‘So, am I getting better?’ asked Kai.

‘You already know the answer to that,’ replied Athena. ‘You managed to send a message to an astropath in the Tower of Voices, and it almost drained you.’

‘Still, it’s an improvement, yes?’

‘Fishing for praise won’t do you any good,’ said Athena. ‘I won’t give it out for anything less than the full return of your abilities.’

‘You’re a hard woman.’

‘I’m a realistic one,’ said Athena. ‘I know I can save you from the hollow mountain, but I need you to know it too. You have to be able to send messages off-world, to starships a sector over, and you need to send them accurately. You’ll have a choir for the last part, but you know as well as I do that the best of us work alone. Are you ready for that? I don’t think so.’

Kai shifted uncomfortably in his seat, fully aware that Athena was right.

‘I don’t feel safe hurling my mind out too far,’ he said.

‘I know, but you’re no use to the Telepathica unless you will.’

‘I… I want to, but… you don’t know…’

Athena leaned forward in her chair, the electro-magnetics of its repulsor plates setting Kai’s teeth on edge.

‘I don’t know what? That we take risks and brave horrors that even the most heroic Army soldier or Legionary wouldn’t be able to comprehend? That every day we could be corrupted by the very powers that make us useful? That we are in the employ of an empire that would collapse without, yet fears us almost as much as the enemies at our frontiers? Oh, I am verymuch aware of that, Kai Zulane.’

‘I didn’t mean–’

‘I don’t care what you meant,’ snapped Athena. ‘Look at me: I’m a freakish cripple that any medicae worthy of the name would have let die the moment he laid eyes on me. But because I’m useful I was kept alive.’

Athena tapped her scarred palm on the metal of her chair. ‘Not that this is any kind of life, but we all have our burdens to bear. I have mine, and you have yours. I deal with mine, and it’s time you dealt with yours.’

‘I’m trying,’ said Kai.

‘No, you’re not. You’re hiding behind what happened to you. I’ve read the report of what happened on the Argo. I know it was terrible, but what good do you do by letting yourself get drained in the hollow mountain? You’re better than that, Kai, and it’s time you proved it.’

Kai sat back and ran a hand over his scalp. He smiled and spread his hands out on the table. ‘You know that was almost like a compliment.’

‘It wasn’t meant as one,’ replied Athena, but she returned his smile. The tight skin at her jawline stopped the right corner of her lip from moving, and the gesture was more like a grimace. A robed servitor brought them two mugs of vitamin-laced caffeine. He took a sip and sucked his cheeks in as the bitter flavour filled his mouth.

‘Throne, I’d forgotten how bad the caffeine here is. Not as strong as they make it on Army ships, but pretty damn close.’

Athena nodded in agreement and pushed away the mug in front of her. ‘I don’t drink it anymore,’ she said.

‘Why not? Aside from the fact it tastes like bilge water and you could repair blast damage on a starship’s hull with it.’

‘I acquired a taste for fine caffeine aboard the Phoenician. Her quartermasters and galleymen were the very best, and when you’ve tasted the best, it’s hard to go back.’

‘The Phoenician? That sounds like an Emperor’s Children warship.’

‘It was.’

‘Was?’

‘It was destroyed fighting the Diasporex,’ said Athena. ‘It took a lance hit amidships and broke in two.’

‘Throne! And you were aboard at the time?’

Athena nodded. ‘The engine section was dragged into the heart of the Carollis Star almost immediately. The forecastle took a little longer. A secondary blast took out the choir, and venting plasma coils flooded the ventral compartments in seconds. My guardians got me out of the choir chamber, but not before… Not many of us escaped.’

‘I’m so sorry,’ said Kai, with a measure of understanding. ‘I’m glad you got off though.’

‘I wasn’t,’ said Athena. ‘Not for a while, at least. I was living with a lifetime’s worth of pain every day until Mistress Sarashina and Master Zhi-Meng taught me tantric rituals to make it bearable.’

‘Tantric?’

‘You know how Zhi-Meng works,’ said Athena neutrally.

Kai considered that and said, ‘Maybe they could teach me?’

‘I doubt it. You’re not as broken as me.’

‘No?’ said Kai bitterly. ‘It feels like I am.’

‘Your body is still in one piece,’ pointed out Athena.

‘Your mind is still in one piece,’ countered Kai.

Athena gave a gargled chuckle. ‘Then between us we have a functioning astropath.’

Kai nodded, and the silence between them was not uncomfortable, as though in sharing their hurts they had established a connection that had, until now, been missing.

‘Looks like we are both survivors,’ said Kai.

‘This is surviving?’ said Athena. ‘Throne help us then.’

AT THE HEART of the web of towers within the City of Sight lay the Conduit, the nexus of all intergalactic communication. Carved by an army of blind servitors from the limestone of the mountains, these high-roofed chambers were filled by black-clad infocytes plugged into brass keyboards and arranged in hundreds of serried ranks. Once each telepathic message had been received and interpreted – and sifted by the cryptaesthesians – it was processed and passed on by the Conduit to the intended recipient by more conventional means. Looping pneumo-tubes descended from the shadowed ceilings like plastic vines, wheezing and rattling as they sped information cylinders to and from the clattering, clicking keystrikes of the infocytes.

Overseers in grey robes and featureless silver masks drifted through the ranks of nameless scribes on floating grav-plates that disturbed the scattered sheets of discarded meme-papers covering the floor. The smell of printers’ ink, surgical disinfectant and monotony filled the air alongside a burnt, electrical smell.

Those of the Administratum who had seen the Conduit found the sight utterly soulless and monstrously depressing. Working as an administrator was bad enough, where faceless men and women were lone voices among millions, but at least there was a slim possibility that talent might lift a gifted individual from the stamping, filing, and sorting masses. This repetitive drudgery allowed for no such escape, and few administrators ever returned to the Conduit, preferring to turn a blind eye to its harsh necessity.

Vesca Ordin drifted through the Conduit on his repulsor plate, information scrolling down the inside of his silver mask as his eyes darted from infocyte to infocyte. As his eye glided over each station, a noospheric halo appeared over its operator with a host of symbols indicating the nature of the message being relayed. Some were interplanetary communications, others were ship logs or regularly scheduled checks, but most were concerned with the rebellion of Horus Lupercal.

In all his thirty years of service in the Conduit, Vesca had always prided himself on making no judgement on the messages he passed. He was simply one insignificant pathway among thousands through which the Emperor ruled the emerging Imperium. It did not become a messenger to get involved. He was too small in the grand scheme of things, just an infinitesimally tiny cog in an inconceivably vast machine. He had always been content in the certainty that the Emperor and his chosen lieutenants had a plan for the galaxy that was unfolding with geometric precision.

The Warmaster’s treachery had seen that certainty rocked to its foundations.

Vesca saw the glaring red symbol that indicated a more urgent communication, and he flicked his haptically-enabled gauntlets to bring a copy of the message up onto his visor. Another missive from Mars, where loyalist forces were struggling to gain a foothold in the Tharsis quadrangle after insurrection had all but destroyed the red planet’s infrastructure.

The Martian campaign was not going well. The clade masters had taken it upon themselves to insert numerous operatives in an attempt to decapitate the rebel leadership, but the killers were finding it next to impossible to penetrate the rigorous bio filters and veracifiers protecting the inner circles of the rebel Mechanicum Magi. This was yet another death notice bound for one of the clade temples. Callidus this time.

Vesca sighed, flicking the message back to the station. It seemed distasteful that the Imperium should rely on such shadow operatives. Was the threat of the Warmaster so great that it required such agents and dishonourable tactics? The fleets of the seven Legions despatched to bring Horus Lupercal to heel were likely even now waging war on Isstvan V, though confirmation of victory had yet to filter through from the various astropathic relays between Terra and the Warmaster’s bolthole.

The daily vox-announcements spoke of a crushing hammerblow that would smash the rebels asunder, of the Warmaster’s treachery inevitably destroyed.

Then why the use of assassins?

Why the sudden rush of messages sent from the Whispering Tower to the fleets forming the second wave behind the Iron Hands, Salamanders and Raven Guard? These were concerns that normally did not trouble Vesca, but the assurances being passed throughout the Imperium seemed just a little too strident and just a little too desperate to sound sincere.

More and more messages wreathed in high-level encryption were being sent from Terra to the expeditionary fleets in order to determine their exact whereabouts and tasking orders. A veteran of the Conduit, Vesca had begun to realise that the Imperium’s masters were desperately trying to ascertain the location of all their forces and to whom they owed their loyalty. Had the Warmaster’s treachery spread further than anyone suspected?

Vesca floated over to a terminal as a request for confirmation icon shimmered to life over the terminal of an infocyte. Despite each operative being hard-wired to a terminal, the staff of the Conduit were not lobe-cauterised servitors. They were capable of independent thought, though such things were frowned upon.

A noospheric tag appeared over the head of the infocyte.

‘Operative 38932, what is the nature of your query?’

‘I… uh, well, it’s just…’

‘Spit it out, Operative 38932,’ demanded Vesca. ‘If this is important, then clarity and speed must be your watchwords.’

‘Yes, sir, it’s just that… it’s so unbelievable.’

‘Clarity and speed, Operative 38932,’ Vesca reminded him.

The infocyte looked up at him, and Vesca saw the man was struggling to find the words to convey the nature of his request to him. Language was failing him, and whatever it was he had to ask was finding it impossible to force its way out of his mouth.

Vesca sighed, making a mental note to assign Operative 38932 a month’s retraining. His repulsor disc floated gently downwards, but before he could reprimand Operative 38932 for his lax communication discipline, another request for confirmation icon appeared over a terminal on the same row. Two more winked to life on another row, followed by three more, then a dozen.

In the space of a few seconds, a hundred or more had flickered into existence.

‘What in the world?’ said Vesca, rising up to look over the thousands of infocytes under his authority. Like the visual representation of a viral spread, white lights proliferated through the chamber with fearsome rapidity. The infocytes looked to their overseers, but Vesca had no idea what was going on. He floated down to Operative 38932’s terminal and ripped the sheet of meme-paper from his trembling fingers.

He scanned the words printed there, each letter grainy and black from the smudged ink of the terminal. They didn’t make sense, the words and letters somehow jumbled in the wrong order in a way that was surely a misinterpretation.

‘No, no, no,’ said Vesca, shaking his head and relieved to have found the solution. ‘It’s a misinterpreted vision, that’s all it is. The choirs have got this one wrong. Yes, it’s the only possible explanation.’

His own hands were shaking and no matter how hard he tried to convince himself that this was simply a misinterpreted vision, he knew it was not. An incorrect vision might have triggered two or three requests for confirmation, but not thousands. With a sinking feeling in his gut that was like having the air sucked from his lungs, Vesca Ordin realised his infocytes were not requesting confirmation on the veracity of the message.

They were hoping he would tell them it wasn’t true.

The meme-paper slipped from his fingers, but the memory of what was printed there was forever etched on the neurons of his memory, each line a fresh horror building on the last.

Imperial counter-strike massacred on Isstvan V.

Vulkan and Corax missing. Ferrus Manus dead.

Night Lords, Iron Warriors, Alpha Legion and Word Bearers are with Horus Lupercal.

HIGH ON THE western flank of the mountain known as Cho Oyu, a graceful villa of harmonious proportions sits upon a grassy plateau. Sunlight reflects from its white walls and shimmers upon the red-clay tiles of the roof. A thin line of smoke curls from a single chimney, and a number of custom-bred doves sit along the ridgeline of the roof. A thin, square tower rises from the north-eastern corner of the villa like a lonely watch tower on a great wall or a lighthouse set to guide seafarers to safety.

Within this tower, Yasu Nagasena stands before a wooden stretching frame, upon which is a rectangle of white silk held in place with silver pins. Cho Oyu is the old name for this mountain, words in a language that has long since been assimilated into a tongue that in turn has been outgrown and forgotten. The migousay it means the Turquoise Goddess, and though the poetry of that name appeals to Nagasena, he prefers the sound of the dead words.

The tower overlooks the Imperial Palace and affords a spectacular view of the hollow mountain to the east. Nagasena does not look at the hollow mountain. It is an ugly thing, a necessary thing, but he never paints it, even when he paints the landscapes of the east.

Nagasena dips his brush into a pot of blue dye and applies it lightly within the boundary lines he has previously applied to prevent the colour bleeding into the material. Painting in the freehand mo-shuistyle, he lays depths of sky to the fabric and nods to himself as he watches the colour flow.

He is tired. He has been painting since dawn, but he wants to finish this picture today. He feels he might never finish it if he does not do so today. His bones ache from standing so long. Nagasena knows he has seen too many winters to indulge in such foolishness, but he still climbs the seventy-two steps to the tower’s uppermost chamber every day.