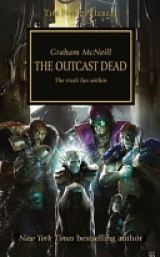

Текст книги "The Outcast Dead"

Автор книги: Грэм Макнилл

Жанр:

Боевая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

The lieutenant marches over to Golovko and hands him a sealed, one-time message slate.

A code wand slides from Golovko’s gauntlet and the slate flickers into life. Softly glowing text appears on its smooth surface, and the man’s face breaks into a grin of feral anticipation.

Nagasena has seen that look before, and he does not like it.

‘What does the message say?’ he asks, though he fears he knows the answer.

Golovko hands the message slate to Saturnalia, who scans its contents with a nod that confirms what Nagasena is already suspecting. He turns away as Saturnalia offers him the slate.

‘We are no longer hunters,’ says Nagasena. ‘Are we?’

‘No,’ says Saturnalia. ‘We are a kill team.’

TWENTY-ONE

Catharsis

I Might Kill You

The Thunder Lord

ROXANNE THREW HERSELF into Kai’s arms with the passion of a long lost lover, wrapping him so tightly that he thought he might break. He returned her embrace, relishing the closeness of another human body and the sight of someone familiar. He and Roxanne had worked together on the Argofor many years, though the strict code of conduct enforced upon all Ultramarines vessels had prevented them from becoming truly close.

‘You’re going to break my ribs,’ said Kai, though he didn’t want her to let go.

‘They’ll heal,’ said Roxanne, pressing even tighter. ‘I never thought I’d see you again.’

‘Nor I you,’ he said, as she finally released him and took a step back, though she kept a grip on his shoulders.

‘You look terrible,’ said Roxanne. ‘What happened to your eyes? After they separated us on the Lemuryan plate, they wouldn’t tell me where you were.’

‘Castana’s armsmen picked me up and took me to the medicae facilities on Kyprios then left me in the care of an idiot,’ said Kai with a sneer. ‘But when the Patriarch realised they might be held liable for the loss of the Argo, they threw me back to the City of Sight.’

‘Bastards,’ said Roxanne. ‘They took me back to our estates in Galicia and tried to hide me away like I didn’t even exist.’

‘Why?’

‘I was an embarrassment to them,’ said Roxanne with a dismissive shrug. ‘A Navigator who can’t even guide a ship home in the same system as the Astronomican isn’t much of a Navigator.’

‘That’s insane,’ he said. ‘You can’t guide a ship when it’s in the middle of a warp storm.’

‘I told them that,’ she said with an exaggerated gesture, ‘but it doesn’t look good when a ship is lost. The Navigator’s always the first one people want to blame.’

‘Or the astropath,’ whispered Kai.

He felt her scrutiny, and returned it. The last time Kai had seen Roxanne, she had been a physical and emotional wreck, as haunted by the unending screams of their dead crew as he had been, but her aura showed little sign of that trauma.

Roxanne guided him from the aisle to find a seat in the pews, taking his arm as though he were blind or infirm.

‘I cansee you know,’ he said. ‘Probably better than you.’

‘Typical,’ said Roxanne. ‘It takes losing your eyes to make you see things clearly.’

He smiled as Roxanne took hold of Kai’s skeletally thin hands. He felt the warmth of her friendship, but instead of recoiling, he let it wash over him like a cleansing balm. Ever since he had been evacuated from the wreck of the Argo, Kai had been treated like a leper or an invalid, and to be viewed as an equal was just about the most wonderful thing anyone had done for him.

‘So what are you doing here?’ asked Kai, hoping to steer the conversation away from the Argo. ‘This doesn’t seem like your kind of place.’

‘I suppose not, but it turns out it’s justmy kind of place.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘I’m Castana,’ said Roxanne. ‘I’ve never wanted for anything in my life, and that meant I didn’t appreciate anything I was ever given. If I broke something or lost something, it would be instantly replaced. Being with the people of the XIII Legion taught me how selfish I’d been. When I returned to our estates I couldn’t face going back to the person I was. So I left.’

‘And you came here?’ said Kai. ‘Seems like a bit of an extreme reaction.’

‘I know, but, like I said, I’m Castana, we don’t do things in half measures. At first I was just going to run off to teach my family that they couldn’t treat me like a child. Then, when they realised how much they needed me, they’d come for me and I’d have earned their respect.’

‘But they didn’t come, did they?’

‘No, they didn’t,’ said Roxanne, but there was no sadness to her at the idea of being abandoned by her family. ‘I found a place to stay, but I still had nightmares about the Argo, and it was eating me up inside. I knew what happened wasn’t my fault, but I couldn’t stop thinking about it. One day I heard about a place in the Petitioner’s City where anyone could lay their dead to rest and find peace. So I made my way here and volunteered to help in whatever way I could.’

‘Did it help? With the nightmares, I mean?’

Roxanne nodded. ‘It did. I thought I’d stay a few days, just to clear my head, but the more I helped people, the more I knew I couldn’t leave. When you’re surrounded by death every day it gives you perspective. I’ve heard hundreds of stories that would break your heart, but it showed me that what I’d gone through wasn’t any worse than what these people live with every day.’

‘And what about Palladis Novandio, what’s his story?’

He sensed reluctance in Roxanne’s aura, and immediately regretted the question.

‘He suffered a great loss,’ she said. ‘He lost people he loved, and he blames himself for their deaths.’

Kai turned to watch Palladis Novandio as he spoke in a low voice with the people of his temple, now understanding a measure of the man’s enveloping grief. He recognised the all-consuming guilt and desire for punishment as the mirror of his own.

‘Then we’re very similar,’ whispered Kai.

‘You blame yourself for what happened on the Argo, don’t you?’ said Roxanne.

Kai tried to give a glib answer, to deflect her question, but the words wouldn’t come. He could read auras or use his psychic abilities to understand emotions without effort, yet he would not turn that insight upon himself for fear of what he might learn.

‘It was my fault,’ he said softly. ‘I was in a nunciotrance when the shields collapsed. I was the way in for the monsters. I was the crack in the defences. It’s the only explanation.’

‘That’s ridiculous,’ said Roxanne. ‘How can you think like that?’

‘Because it’s true.’

‘No,’ said Roxanne firmly. ‘It’s not. You didn’t see what was happening beyond the ship. I saw what hit us, and anyship would have been overwhelmed. A squall of warp cyclones blew up out of nowhere and hit a vortex of high-energy currents coming in from the rimward storms. No one saw it coming, not the Nobilite Watcher Guild, not the Gate Sentinels, no one. It was a one in a million, one in a billion, freak confluence. Given what’s happening here on Terra and out in the galaxy, I’m surprised there aren’t more of them surging to life. It’s a mess out there in the warp, and you’re lucky you don’t see it.’

‘You might have seen it, but I heard it,’ said Kai. ‘I heard them die.’

‘Who?’

‘All of them. Every man and woman on the ship, I heard them die. All their terrors, all their lost dreams, all their last thoughts. I heard them all, screaming at me. I can still hear them whenever I let my guard down.’

Roxanne gripped his hand fiercely and he felt the power of her stare, though he had no eyes with which to return it. The force of her personality blazed like a solar corona, and only now did Kai realise how strong she was. Roxanne was Castana, and there were few of that clan who lacked for self-assuredness.

‘They tried to blame us both for the loss of the Argo, so what does that tell you about how little they know about whose fault it was? Someone had to be responsible. Something terrible had happened, and it’s human nature to want someone else to pay for it. They told me, day and night, that it was my fault, that I’d done something wrong, that I had to retrain. But I said no, I told them I knew it wasn’t my fault. I knewthere was nothing I or anyone else could have done to save that ship. It was lost no matter what I did. It was lost no matter what youor anyone else did.’

Kai listened to her words, feeling each one slip past his armour of certainty like poniards aimed at his heart. He had told himself the same things over and over again, but the mind has no greater accuser than itself. The Castanas told him he caused the death of the Argo, and he had believed them because, deep down, he wanted to be punished for surviving.

They needed a scapegoat, and when one of their own wouldn’t fall on her sword, he had been the next best thing: a willing victim. Kai felt the black chains of guilt within him slip, a tiny loosening of their implacable hold. Not completely, nothing so simple as the words of a friend could cause them to break their grip so easily, but that they had slackened at all was a revelation.

He smiled and reached up to touch Roxanne’s face. She was wary of the gesture, as were all Navigators, for they disliked other people’s hands near their third eye. Her cheek was smooth and the brush of her hair against his skin felt luxurious. These moments of human contact were the first Kai had known in months that didn’t involve someone wanting to take something from him, and he let it linger, content to take each breath as a free man.

‘You’re cleverer than you look, do you know that?’ said Kai.

‘Like I said, this place gives you perspective, but how would you know? You can’t even see me with that bandage over your eyes. You never did say what happened to them.’

And Kai told her all that had befallen him since his arrival at the City of Sight, his retraining, the terror of the psychic shockwave that had killed Sarashina and placed something so valuable within his mind that people were willing to kill to retrieve it. He told of their escape from the Custodians’ gaol, the crash and their flight through the Petitioner’s City, though this last part of his recall was hazed with uncertainty and half-remembered visions where fear and dreams collided. He told Roxanne of the Outcast Dead’s plans to bring him to Horus Lupercal, and the mention of the Warmaster’s name sent a tremor of fear through her aura.

When Kai finished, he waited for Roxanne to ask about what Sarashina had placed in his mind, but the question never came, and he felt himself fall a little in love with her. She looked over at the door through which the Space Marines had taken their dead.

‘You can’t let them take you to the Warmaster,’ she said.

‘You think I owe the Imperium anything, after all they did to me?’ said Kai. ‘I won’t just hand myself over to the Legio Custodes again.’

‘I’m not saying you should,’ said Roxanne, taking his hands again. ‘But even after all that’s happened, you’re not a traitor to the Imperium, are you? If you let them take you to Horus, that’s what you’ll be. You know I’m right.’

‘I know,’ sighed Kai. ‘But how can I stop them from taking me? I’m not strong enough to fight them.’

‘You could run.’

Kai shook his head. ‘I wouldn’t last ten minutes out there.’

Roxanne’s silence was all the agreement he needed.

‘So what are you going to do?’ she asked at last.

‘I haven’t the faintest idea,’ said Kai. ‘I don’t want to be used anymore, that’s all I know for sure. I’m tired of being dragged from pillar to post. I want to take control of my own destiny, but I don’t know how to do that.’

‘Well you’d better figure it out soon,’ said Roxanne, as the heavy door at the rear of the temple swung open. ‘They’re back.’

THE DEAD WERE ashes. Argentus Kiron and Orhu Gythua were no more, their bodies consumed in the fire. Tagore felt numb at their deaths, knowing he should feel a measure of grief at their passing, but unable to think beyond the anticipation of his next kill. Ever since the battle with Babu Dhakal’s men, his body had been a taut wire, vibrating at a level that no one could see, but which was ready to snap.

It felt good to have blood on his hands, and the butcher’s nails embedded in his skull had rewarded him for his kills with a rush of endorphins. Tagore’s hands were clenched tightly, unconsciously balled into fists as he scanned the room for threats, avenues of attack and choke points. The people in here were soft, emotional and useless. They wept tears of what he presumed were sadness, but he could not connect to that emotion any more.

While Severian and Atharva spoke to the grey-haired man who owned this place – he could not bring himself to use the word temple– Tagore sent Subha and Asubha to secure their perimeter. His breath was coming in short spikes, and he knew his pupils were dilated to the point of being totally black. Every muscle in his body sang with tension, and it took all Tagore’s iron control to keep himself from lashing out at the first person that looked at him.

Not that anyone dared look at a man who was so clearly dangerous. No eye would meet his, and he took a seat on a creaking bench to calm his raging emotions. He wanted to fight. He wanted to kill. There was no target for his rage, yet his body craved the release and reward promised by the pulsing device bolted to the bone of his skull.

Tagore had spoken of martial honour, but the words rang hollow, even to him. They were spoken by rote, and though he wanted to feel cheated at how little they meant to him, he couldn’t even feel that. They were good words, ones he used to believe in, but as the tally of the dead mounted, the less anything except the fury of battle came to mean. He knew exactly how many lives he had taken, and could summon each killing blow from memory, but he felt no connection to any of them. No pride in a well-placed lunge, no exultation at the defeat of a noteworthy foe and no honour in fighting for something in which he believed.

The Emperor had made him into a soldier, but Angron had wrought him into a weapon.

Tagore remembered the ritual breaking of the chains aboard the Conqueror, that mighty fortress cast out into the heavens like the war hound of a noble knight. The Red Angel, Angron himself, had mounted the chain-wrapped anvil and brought his callused fist down upon the mighty knot of iron. With one blow he had severed the symbolic chains of his slavery, hurling the sundered links into the thousands of assembled World Eaters.

Tagore had scrapped and brawled with his brothers in the mad, swirling mêlée to retrieve one of those links. As a storm-sergeant of the 15th Company, he had been ferocious enough to wrest a link from a warrior named Skraal, one of the latest recruits to be implanted with the butcher’s nails. The warrior was young, yet to master his implants, and Tagore had pummelled him without mercy until he had released his prize.

He had fashioned that link into the haft of Ender, his war axe, but that weapon was now lost to him. Anger flared at the thought of the weapon that had saved his life more times than he could count in the hands of an enemy. Tagore heard the sound of splintering wood, and opened his eyes in expectation of violence, but from the pinpricks of blood welling in his palms, he knew he had crushed the projecting lip of the bench.

Tagore closed his eyes as he spoke the words to the Song of Battle’s End.

‘I raise the fist that struck men down,

And salute the battle won.

My enemy’s blood has baptised me.

In death’s heart I proved myself,

But now the fire must cool.

The carrion crows feast,

And the tally of the dead begins.

I have seen many fall today.

But even as they die, I know

That our blood too is welcome.

War cares not from whence the blood flows.’

Tagore let out a shuddering breath as he spoke the last word, feeling the tension running through his body like a charge ease. He unclenched his fists, letting the splintered wood fall to the floor. He felt a presence nearby and inclined his head to see a young boy sitting next to him. Tagore had no idea how old this boy was, he had no memory of being young, and mortal physiology changed so rapidly that it was impossible to gauge the passage of years on their frail flesh.

‘What was that you just said?’ asked the boy, looking up from a pamphlet he was reading.

Tagore looked around, just to be sure the boy was, in fact, addressing him.

‘They are words to cool the fires of battle in a warrior’s heart when the killing is done,’ he said warily.

‘You’re a Space Marine, aren’t you?’

He nodded, unsure what this boy wanted from him.

‘I’m Arik,’ said the boy, holding out his hand.

Tagore looked at the hand suspiciously, his eyes darting over the boy’s thin frame, unconsciously working out where he could break his bones to most efficiently kill him. His neck was willow thin, it would take no effort at all to break it. His bones were visible at his shoulders and ridges of ribs poked through his thin shirt.

It would take no effort at all to destroy him.

‘Tagore, storm-sergeant of the 15th Company,’ he said at last. ‘I am World Eater.’

Arik nodded and said, ‘It’s good you’re here. If Babu Dhakal’s men come back then you’ll kill them, won’t you?’

Pleased to have a subject to which he could relate, Tagore nodded. ‘If anyonecomes here looking for me, I’ll kill him.’

‘Are you good at killing people?’

‘Very good,’ said Tagore. ‘There’s nobody better than me.’

‘Good,’ declared Arik. ‘I hate him.’

‘Babu Dhakal?’

Arik nodded solemnly.

‘Why?’

‘He had my dad killed,’ said the boy, pointing to the kneeling statue at the end of the building. ‘Ghota shot him right there.’

Tagore followed the boy’s pointing finger, noting the silver ring on his thumb, its quality and worth clearly beyond his means. The statue was of a dark stone, veined with thin lines of grey and deeper black, and though it had no face, Tagore felt sure he could make out where its features were meant to be, as if the sculptor had begun his work, but left it unfinished.

‘Ghota killed one of my… friends too,’ said Tagore, stumbling over the unfamiliar word. ‘I owe him a death, and I always repay a blood debt.’

Arik nodded, the matter dealt with, and returned to reading his pamphlet.

Tagore was in unfamiliar territory, his skills of conversation limited to battle-cant and commands. He was not adept in dealing with mortals, finding their concerns and reasoning impossible to fathom. Was he supposed to continue speaking to this boy, or were their dealings at an end?

‘What are you reading?’ he asked after a moment’s thought.

‘Something my dad used to read,’ said Arik, without looking up. ‘I don’t understand a lot of it, but he really liked it. He used to read it over and over again.’

‘Can I see it?’ asked Tagore.

The boy nodded and handed over the sheet of paper. It was thin and had been folded too many times, the ink starting to smudge and bleed into the creases. Tagore was used to reading tactical maps or orders of battle, and this language was a mix of dialects and words with which he was unfamiliar, yet the neural pathways of his brain adapted with a rapidity that would have astounded any Terran linguist.

‘Men united in the purpose of the Emperor are blessed in his sight and shall live forever in his memory,’ read Tagore, his brow furrowed at the strange sentiment. ‘I tread the path of righteousness. Though it be paved with broken glass, I will walk it barefoot; though it cross rivers of fire, I will pass over them; though it wanders wide, the light of the Emperor guides my step. There is only the Emperor, and he is our shield and protector.’

Tagore looked up from his reading, feeling the pulse of his implant burrowing deep into his skull as his anger grew at these words of faith and superstition. Arik reached over and pointed to a section further down the pamphlet.

‘The strength of the Emperor is humanity, and the strength of humanity is the Emperor,’ said Tagore, his fury growing the more he read. ‘If one turns from the other we shall all become the Lost and the Damned. And when His servants forget their duty they are no longer human and become something less than beasts. They have no place in the bosom of humanity or in the heart of the Emperor. Let them die and be outcast.’

Tagore’s heart was racing and his lungs drew air in short, aggressive breaths. He crumpled the pamphlet in his fist and let it drop to the ground.

‘Get away from me, boy,’ he said through bared teeth.

Arik looked up, his eyes widening in fear as he saw the change in Tagore.

‘What did I do?’ he said in a trembling voice.

‘I said get away from me!’

‘Why?’

‘Because I think I might kill you,’ growled Tagore.

NAGASENA WATCHES THE building from a projection of rock at the mouth of the canyon, knowing his prey is close. In the streets behind him, six armoured vehicles and nearly a hundred soldiers wait in anticipation of his orders. Though there is only one order to give, Nagasena hesitates to issue it. Athena Diyos and Adept Hiriko wait with them, though there is likely no part in this hunt left for them to play.

Even Nagasena concedes that in the latter stages of a hunt there is a certain thrill, but he feels none of that now. Too much uncertainty has entered his life since he left his mountain home for him to feel anything but apprehension at the thought of facing Kai Zulane and the renegades.

Through the scope of his rifle he can see there are no escape routes from the structure, its statue-covered façade presenting the only obvious way in or out. Hundreds of people are gathered before the building, and they have brought their dead with them. Nagasena understands the need to cling onto the lost, to honour their memory and ensure they are not forgotten, but the idea of praying to them or expecting that they will pass onto another realm of existence is alien to him.

The advanced optics on Nagasena’s scope, obtained at ruinous cost from the Mechanicum of Mars, penetrates the marble frontage, displaying a coloured thermal scan of the building’s interior. Through a fine copper-jacketed wire, that image is displayed on Kartono’s slate.

Perhaps sixty people are inside the temple, and the Legiones Astartes are immediately apparent in their heat signatures as well as their size. It is impossible to pick out which of these people might be Kai Zulane. As Antioch had said, there are five of them, and they are gathered around a much smaller individual. Their heat signatures blur. Something behind their overlarge bodies is scattering the readings from his optics, wreathing the entire image in a grainy static that makes Nagasena’s eyes itch.

‘So much for those expensive bio-filters,’ grunts Kartono, slapping a palm against the side of the slate. The image quality does not improve, but they have enough information to mount an assault on the building with a high degree of success.

‘We should storm the building,’ says Golovko. ‘We have over a hundred men now. There’s nowhere left for them to run. We can end this within the hour.’

‘He’s right,’ says Saturnalia with obvious reluctance to align himself with the Black Sentinel. ‘We have our quarry boxed in.’

‘And that makes them doubly dangerous,’ says Nagasena. ‘There is nothing more dangerous than a warrior who is cornered and has nothing left to lose.’

‘Just like the Creatrix of Kallaikoi,’ says Kartono.

‘Exactly so,’ snaps Nagasena, unwilling to relive that particular memory right now. He still bears scars that will never heal from that hunt.

Saturnalia takes the slate from Kartono’s hands and holds it up in front of Nagasena, as if he has not yet seen it. He taps the hazed images of the five men they have come to kill.

‘There is no reason not to go in,’ says the Custodian. ‘We have our orders, and they are clear. Everyone here is to die.’

Nagasena has read and reread their orders, searching for a way to interpret them in a manner that will not scar his memories for life and result in the deaths of so many innocents, but Saturnalia is right; their orders are without ambiguity.

‘These are Imperial citizens,’ he says, though he knows he is wasting his breath trying to convince Saturnalia to alter his course. ‘We serve them with our deeds, and to betray them like this is wrong.’

‘Wrong? These traitors have been welcomed amongst these people, and they are guilty by association,’ says Saturnalia. ‘I am a warrior of the Legio Custodes, and my duty is the safety of the Emperor, a duty in which there can be no compromise. Who knows what treachery these men may have already spread among the people of the Petitioner’s City? If we allow any they have touched to live, then their betrayal will fester like a rank weed, drawing nourishment from the darkness and growing even greater and more deeply entrenched.’

‘You can’t know that,’ protests Nagasena.

‘I don’t need to knowit, I just need to believe it.’

‘This is your Imperial Truth?’ asks Nagasena, almost spitting the words.

‘It is just the truth,’ says Saturnalia. ‘Nothing more, nothing less.’

Nagasena’s eyes lock with those of Kartono, but he sees nothing in his bondsman’s eyes that give any clue to his emotions. Clade Culexus saw to that. He grips the tightly-wound hilt of Shoujikiand knows he should walk away, but that would be as good as signing his own death warrant. For good or ill, he is bound to this hunt until its end.

He nods, and hates that Saturnalia and Golovko share the triumphant grins of conspirators.

‘Very well,’ he says. ‘Let us get this over with.’

Before any attack order can be given, Kartono gives a shocked breath of surprise. He consults the imagery on his slate and looks up in confusion.

‘We may have a problem,’ he says, pointing down into the canyon. ‘New arrivals.’

ATHARVA WATCHED TAGORE rise from the bench and walk stiffly across the nave as he made his way towards their gathering. The warrior’s aura blazed with anger, the swirling colours of angry bruises and hot, pumping blood. Just touching that fire enflamed Atharva’s own aggression, and he rose into the lower Enumerations to better control himself.

‘We may have a way off Terra,’ said Asubha as Tagore joined them.

The World Eaters sergeant nodded, his teeth still clenched and his skin drained of colour.

‘How?’ he asked.

‘Tell him,’ said Atharva, gesturing to Palladis Novandio.

‘At the top of this scarp is the dwelling place of Vadok Singh, one of the Emperor’s war masons,’ said Palladis with such bitterness and reluctance that it almost made Atharva flinch. ‘He oversees all aspects of the construction work to the palace, and he likes the high perch.’

‘So?’ demanded Tagore, wearing his impatience like a spiked cloak.

‘The warmason likes to observe some of his grander constructions from orbit,’ clarified Palladis. The man did not want them to leave, and only Atharva’s insight had made him divulge this latest morsel of information.

‘You understand now?’ said Severian.

‘He has an orbit-capable craft?’ demanded Tagore, his anger morphing into interest.

‘He does,’ said Palladis.

‘We can get off world,’ said Subha, punching a fist into his palm.

‘Better,’ said Asubha. ‘If we can get to one of the orbital plates, we can get aboard a warp-capable craft.’

‘So we are agreed?’ said Atharva, with a sidelong glance at Palladis Novandio. ‘We are bound for Isstvan?’

‘Isstvan,’ agreed Tagore.

‘The Legion,’ said Asubha and his brother together.

‘Isstvan it is,’ said Severian. ‘I will find us a way to the warmason’s villa.’

Atharva nodded as the Luna Wolf slipped away into the darkness at the rear of the temple.

‘Where will you go once you are off-world?’ asked Palladis Novandio, unable to mask his disappointment. ‘You would not consider remaining here? Where else should the Angels of Death be but a temple dedicated to its name?’

Tagore rounded on the man and lifted him from his feet.

‘I should kill you now for what you have allowed to take root here,’ snarled the World Eater. ‘You call a building a temple, and people will find gods within it.’

‘What are you talking about, Tagore?’ said Atharva.

Tagore held Palladis Novandio at arm’s length, as though the man carried some virulent infection. ‘He is a promoter of false gods. This is no place of remembrance. It is a fane where the Emperor is held up as some kind of divine being. All this, it is all a lie, and he is its chief prophet. I will kill him and we will be on our way.’

‘No!’ cried Palladis. ‘That’s not what we do here, I promise.’

‘Liar!’ bellowed Tagore, drawing his fist back.

Before Tagore could unleash his killing power, the doors of the temple were flung wide and two enormous figures were silhouetted in the glow of a hundred lamps and flickering torches from outside. Fear billowed in with them on a wave of ash-clogged wind, and Atharva suddenly sensed the predatory minds of hunters beyond the walls of the temple.

He recognised Ghota from the battle outside Antioch’s surgery, but the second warrior took his breath away with his sheer scale.

Enormous beyond even Ghota’s monstrous size, the warrior was taller than Tagore and broader in the shoulder than Gythua had been. He was clad in a suit of burnished war plate the colour of bronze and midnight. Fashioned in a form worn by a band of warriors long dead, he wore the armour as though born to it. At his side was an outdated model of bolter, and across his back was sheathed a vast-bladed sword.

‘I am the Thunder Lord,’ said Babu Dhakal. ‘And you have something I want.’