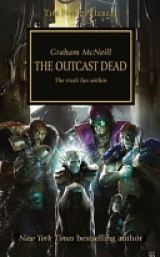

Текст книги "The Outcast Dead"

Автор книги: Грэм Макнилл

Жанр:

Боевая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

‘Intriguing. And how many of these giants were there?’

The man coughed a wad of bright, arterial blood and shook his head. ‘Six, seven, I ain’t sure, but they had a scrawny fella with them too. Didn’t look like much, but one of the big men was making special sure he took care of that one.’

‘Where are these men now?’

‘I don’t know, they could be anywhere now!’

‘Ghota…’

Ghota leaned down and hauled the man upright until his feet were dangling just above the floor. His arm was fully extended, but he gave no sign that this feat of strength was any effort whatsoever. With his free hand, Ghota drew an enormous pistol from his holster, a weapon that bore an eagle stamped onto its foreshortened barrel.

‘I believe you. After all, why would you speak false when you know you are going to die anyway?’

‘Last I saw they was heading towards the Crow’s Court, I swear!’

‘The Crow’s Court? What draws them in that direction, I wonder?’

‘I don’t know, please!’ sobbed the labourer. ‘Maybe they’re taking the wounded one to Antioch.’

‘That old fool?’ laughed the wet voice. ‘What would he know of the miraculous anatomy of the vaunted Legiones Astartes?’

‘Anyone desperate enough to crash here might risk it,’ said Ghota.

‘They might indeed,’ agreed the figure on the throne. ‘And I have to ask what brings warriors like that to my city.’

The figure stood and took a step down from his throne. The labourer whimpered in fear at the sight of the man, a grossly misshapen giant with a physique so enormous he was more powerful than Ghota. Muscles like mountains clung to his body, barely contained by curved plates of beaten iron and ceramite strapped to his body in imitation of the battle plate worn by the Legiones Astartes.

Babu Dhakal approached the sobbing labourer and bent down until their faces were centimetres apart: one a blandly unremarkable face worn thin by a lifetime of work, the other a pallid corpse face of dry, desiccated skin pierced by numerous gurgling tubes and criss-crossed by metal sutures holding the cancerous flesh in place. A thin Mohawk of hair ran in a widow’s peak from the clan lord’s studded forehead to the nape of his neck, and jagged lightning bolt tattoos radiated from this centreline in a jagged arc to his shoulders.

Like Ghota, his eyes were a nightmare of petechial haemorrhages, red with ruptured blood vessels and utterly devoid of human compassion or understanding. These were the eyes of a killer, the eyes of a warrior who had fought from one side of the world to the other and slaughtered any man who stood in his way. Armies had quailed before this man’s gaze, cities had opened their gates to him and great heroes had been humbled before his might.

A sword as tall as a mortal man was strapped to his back and he drew it slowly and with great care, like a chirurgeon preparing to open a patient.

Or a torturer readying an instrument of excruciation.

Babu Dhakal nodded and Ghota released his grip on the man.

The sword swept out, a blur of steel and red, and a vast gout of crimson splashed to the floor of the warehouse. It hissed and bubbled as it landed on the coals, filling the air with the scent of burned blood. The labourer was dead before he felt the impact of the blade, carved in a neat line from crown to crotch like a side of beef. The shorn halves of the man crumpled to the floor, and Babu Dhakal cleaned his blade on Ghota’s bear-pelt cloak.

‘Hang those up,’ he said, gesturing to the lifeless sides of meat splayed on the floor as he sheathed his sword over his shoulder. Babu Dhakal returned to his throne and lifted an enormous weapon from a hook welded to its side.

It gleamed with all the love and care that had been lavished upon it, a hand-finished assault rifle crafted in one of the first manufactories to produce such weapons. It bore a carven eagle upon its barrel, and though it was much larger than the pistol borne by Ghota, it clearly belonged to the same class of firearm.

It was a boltgun, but no warrior of the Legiones Astartes had borne a weapon of such brutal, archaic design since the union of Terra and Mars.

‘Ghota,’ said Babu Dhakal with undisguised hunger. ‘Find these warriors and bring them to me.’

‘It shall be done,’ said Ghota, hammering a fist to his chest.

‘And Ghota…’

‘Yes, my subedar?’

‘I want them alive. The gene-seed is no use to me in corpses.’

SIXTEEN

A Different Drum

Mechlairvoycance

Blind

SEVERIAN LED THEM past to the ruined shell of what had once been a haphazardly built tenement block, but which had collapsed after one too many floors had been added to an already unstable and poorly built structure. Atharva sensed the lingering anger of those who had died here, the psychic echoes that had not yet been dispersed and reabsorbed by the Great Ocean.

Sadness dwelled here, and even those without sensitivity to the workings of the aether stayed away. In a city of millions, Severian managed to find them a deserted corner in which to take refuge and catch their breath. The Luna Wolf claimed they had come here unseen, though Atharva found it hard to imagine that their passing had gone completely unnoticed.

Water fell in runnels from the cracked floors above them, a zigzagging collection of sheet metal and timber that looked horribly unsafe, but which Gythua claimed was in no danger of imminent collapse. The Death Guard was sitting propped up against one wall with Kiron speaking to him in low tones, while the World Eater twins were examining the two blades they had taken from the dead Custodians. The power cell housings were open and it seemed they were attempting to get the energy fields working again.

Severian knelt by the largest opening in the buckled wall, scanning the approaches to their refuge for any signs of the hunt that must surely be closing in on them. Kai lay sprawled on his side in the driest part of the structure, his chest rising and falling in the gentle rhythm of sleep. The mortal was exhausted, his mind and body on the verge of complete collapse, but Atharva knew he would go on. The power that had touched his mind would not allow him to fail, and Atharva had to know what that was. Like all in his Legion, he abhorred ignorance, viewing it as a failure of effort and determination. Whatever was in Kai’s mind had been deemed vital enough that the Legio Custodes had brought in psychic interrogators, and that made it a personal challenge that he be the one to extract it.

Atharva closed his eyes and let his subtle body drift from his flesh, feeling the lightness of being that came with loosening the bonds of corporeal confinement. He could not remain parted from his body for long, as their hunters would be sure to have psi-hounds in their midst, and a subtle body would be a shining beacon to them.

The mental noise of the Petitioner’s City washed over Atharva, a background haze of a million people’s thoughts. Banal and irrelevant, he filtered out their hopes of one day being admitted within the walls of the palace, their fear of the gangs, their despair and their numbness. Here and there, he felt the unmistakable hint of a latent psyker, a talented individual with the potential to develop their abilities into something wondrous.

It saddened him that these gifted ones would never have that chance on Terra. Had they been born on Prospero, their abilities would have been nurtured and developed. The great work begun by the Crimson King before the betrayal of Nikaea had offered blinkered humanity a chance to unlock the full potential of their brilliant minds, but Atharva knew that fragile moment when dreams take flight had been shattered forever and could never be remade.

Yet even as the thoughts of the city faded, Atharva sensed another presence hidden within its depths, something powerful and alien. His subtle body felt its nearness and he fought the urge to fly the aether towards it. Somewhere close, something had found a way through the veil that separated this world from the Great Ocean, a passage that had escaped the notice of the material world’s inhabitants.

And as Atharva became aware of this intelligence, it too became aware of him and shrank back into whatever shell currently hosted its form. He could still sense it; something that powerful could not completely conceal its presence, it was a thorn in the flesh of the world that would never completely heal.

Atharva dismissed it for now and turned his thoughts to Kai Zulane. He let his body of light drift into the upper reaches of the astropath’s mind, sifting through the clutter of his waking thoughts and the panic and fear of his last few weeks. The savage scarring left by the neurolocutors angered him, and Kai shifted in his dreams as that anger bled into his thoughts.

Atharva saw fleeting images of a vast desert and a towering fortress he recognised as the long-vanished Urartu fortress of Arzashkun. A dry, but informative text of Primarch Guilliman had described it, and a copy of that work resided in the Corvidae library in Tizca. Why would Kai Zulane be dreaming of such a place? True, he had served with the XIII Legion, and it was not beyond the realms of possibility that he might have seen the original work somewhere in Ultramar, but why would he have need to dream of it?

Pushing deeper into that dream, Atharva smelled the aroma of the souk, the fragrance of hookah smoke and the spiced flavour of a dead culture. He had no frame of reference for these sensations, but he sensed their importance to whatever secret Kai held within his mind.

What did the Eye want with this mortal? What could be so important that it would be placed within such a fragile vessel instead of someone worthy of its protection?

Atharva smiled as he recognised a hint of jealousy in his thoughts.

He pressed harder against the edge of Kai’s dreams, employing skills beyond the imaginations of the simpletons who had tried to open his mind. He saw the desert and the vast emptiness it represented. He recognised the significance of the great fortress and the prowling shadow that circled it with a predator’s patience. This was Kai’s refuge, but it would prove wholly inadequate to keep a truth-seeker of Atharva’s skill from eventually breaching its defences.

With a thought, Atharva was at Arzashkun’s mighty gates and he looked up at the brilliant whiteness of the fortress’s many towers and gilded rooftops. Portions of its silhouette were missing, and he could picture the neurolocutors disassembling its structure in an effort to intimidate their captive.

‘You only drove him deeper in,’ said Atharva.

He extended his hand towards the great defensive gates and willed them to open. When nothing happened, he repeated the gesture. Again the gates remained stubbornly closed to him, and Atharva felt a prescient sensation of warning as the sand around him erupted with black streamers of oozing menace. Screams of the dying enveloped him and grasping, clawed hands of glistening black matter pulled at his subtle body, tearing shards of light from his immaterial form that would leave black repercussions on his physical body.

Atharva rose up from the cloying morass of horror and fear, irritated that he had allowed himself to be surprised by such base emotions. His body floated high above Arzashkun, but the black ooze rose up like creepers climbing an invisible building towards him. Atharva had the strongest sensation that Kai’s own guilt was shielding the secret within him, and he smiled in admiration for whoever had placed it there.

‘Very clever,’ he said. ‘The defences can only ever be opened from the inside.’

ATHARVA OPENED HIS eyes and groaned as he allowed his subtle body to return to his flesh abode in the material world. The quality of light in their hiding place had changed, the sun drawing close to the western horizon as night drew in on the mountains.

‘Where did you go?’ said Tagore, and Atharva flinched as he realised the World Eater was right beside him.

‘Nowhere,’ said Atharva.

Tagore laughed. ‘For someone supposed to be clever, you are a terrible liar.’

Atharva had to concede the point. ‘I am a scholar, Tagore. I deal in facts and facts are always true. Lies are for lesser minds who cannot face the truth.’

‘You are a warrior, Atharva,’ said Tagore. ‘First and foremost, that is what you were created to be. Do not forget the truth of thatfact.’

‘I have fought my share of wars, Tagore,’ said Atharva. ‘But it is always such a brutal business that teaches nothing except how to destroy. Knowledge can only ever be lost in war, and such loss is abhorrent to me.’

Tagore considered this and jerked a thumb in Kai’s direction.

‘So we broke him out and he’s still alive. Are you going to tell me what’s so important about him and why we risked our lives for him?’

‘I am not sure yet,’ said Atharva. ‘I was attempting to go into his mind to find out what the Legio Custodes wanted from him, but it is hidden deep.’

‘Something to do with the Emperor,’ said Tagore. ‘That’s the only reason for the Custodians to get involved.’

‘You could be right,’ agreed Atharva.

‘Now you will tell me why you spoke with the hunter on the steps of the Preceptory.’

Atharva had been waiting for this. There was no mistaking the vibrating chord of anger within the World Eater sergeant, and for all Tagore’s lack of subtlety, he would be swift to spot any falsehood.

‘It is hard to explain,’ Atharva began, holding up a hand to forestall Tagore’s ire, ‘but I do not say that to evade an answer. My Legion has many of its warriors dedicated to the arts of divination, sifting the currents of the Great Ocean – the warp as some know it – for threads that link past, present and future. Everything that ever was and ever will be can be read in its depths, but sorting what willbe from what couldbe requires decades of study, and even then it is an imprecise art.’

Atharva smiled, wondering what Chief Librarian Ahriman would make of that.

‘Are you one of these seers?’ asked Kiron, moving away from the recumbent form of the unconscious Gythua. ‘Can you see the future?’

‘I am Adeptus Exemptus, a high-ranking member of my fellowship, and I have trained in all the arts of my Legion, but I am not skilled enough to future-see with any degree of certainty.’

‘But you saw something that day, didn’t you?’ asked Asubha, the blade in his hand crackling with power. ‘Something that made you stand aside when you could have warned us of the approach of our attackers.’

‘I did,’ said Atharva. ‘I saw the galaxy overturned, and moving to the beat of a different drum. I saw us as guardians of a secret that could alter the outcome of this rebellion of Horus Lupercal.’

‘Enough riddles,’ snapped Subha. ‘Speak plainly of what you saw.’

‘I can speak only in possibilities, for that is all I have,’ said Atharva. ‘For reasons none of us can guess, Horus has turned on his father, and three of his brothers have turned with him. Lords Angron, Fulgrim and Mortarion have joined Horus in rebellion, but I do not believe they will be the only ones.’

‘Why not?’ asked Tagore.

‘Because Horus is no fool, and he would not risk everything in one gamble on the sands of a dead world. No, Isstvan V is just the beginning of the Lupercal’s plan, and there are players yet to reveal their faces.’

‘So what does this have to do with him?’ asked Kiron, jerking his thumb at Kai.

‘I believe that Kai Zulane knows the outcome of Horus’s grand plan,’ said Atharva.

He paused to let the implications of that sink in, letting each man reach the inevitable question in their own time. In the end it was Asubha who gave it voice.

‘So what happens? Does Horus defeat the Emperor?’

‘I do not know,’ answered Atharva, ‘but either way, Kai Zulane is now the most important man in the galaxy. His life is worth more than any of ours, and thatis why I had us break him from captivity.’

‘But you say the information is locked inside him,’ said Tagore. ‘How do you get it out?’

Atharva sighed. ‘I am not sure I can,’ he said. ‘The information was hidden in the deepest recesses of his guilt, and such an emotion is powerful enough to defeat any interrogation.’

‘Then what use is he?’ demanded Subha. ‘We should kill him and be done with it. All he’ll do is slow us down and get us killed.’

‘There is merit in what Subha says,’ pointed out Kiron. ‘If the future is predestined, what does it matter whether the astropath lives or dies? The outcome will be the same.’

‘I do not believe in predestination,’ said Atharva. ‘By gaining knowledge of the future, we inherit the ability to change it, and I will not allow the future to pass me by and know that I had a chance to shape it.’

‘That smacks of arrogance,’ said Severian, turning from his vigil at the entrance.

Atharva shook his head. ‘Does it? Is it arrogant to want to change the course of a war that will claim hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of lives? Imagine the power of an army that marched to war knowing with absolutecertainty that it could not lose. Now imagine that same army learning that no matter whatthey could not win. Knowledge is power, the Mechanicum know this, and my Legion knows it too. Whoever holds the truth that hides in this astropath’s head, will be the victor in this war.’

‘So what do we do with him?’ asked Kiron.

‘We take him to Isstvan V,’ said Subha. ‘Isn’t it obvious? Our place is with our Legions, and if the Red Angel has thrown in his lot with Horus, then he clearly had a good reason.’

Tagore nodded in agreement and Atharva saw that Kiron believed the idea had merit too. Asubha remained impassive and Severian did not look up. Atharva took a deep breath, knowing that what he was about to say was dangerous.

‘But by the same token, if the Emperor has named them traitors, might he too have had a good reason? Perhaps your Legions are not worthy of your loyalty.’

Tagore surged to his feet, blade in hand.

‘The Legio Custodes call me traitor, and now you too? I should kill you where you sit.’

‘The Phoenician a traitor?’ said Kiron, aiming his plasma carbine at Atharva’s head. ‘I’ll thank you to choose your words with more care, sorcerer.’

Atharva knew he could not back down, but nor could he so baldly assert the facts in the face of such emotional response.

‘How can any of you say for sure what has happened to any of our Legions? When was the last time any of us spent any time alongside our battle brothers? Fifty years? A century? Who can say for sure what their Legion has become in that time? I have not laid eyes upon the Crimson King in over seventy years, and Tagore, it has been over a century since you knelt before Angron.

‘We were locked in Terra’s deepest gaol simply for the insignia on our armour, not the truth in our hearts, so who is to say where our loyalty lies now? Our first loyalty is to the Imperium, is it not?’

‘Any master that puts me in chains is not worthy of my loyalty,’ said Tagore.

‘Perhaps not, but what of our brother Legionaries? What can break such bonds of brotherhood as are forged in war? Is our loyalty now to them alone? Or is it to this fledgling band of brothers we now find ourselves within? Consider this, we have been given a unique chance, a chance to decide for ourselves the master to whom we will swear our loyalty.’

‘A pretty speech,’ said Tagore, tapping the side of his head. ‘But I know where my loyalty lies, it is to the primarch whose words and deeds I have followed into the fires of battle and who granted me the gift of rage bound by steel.’

‘I expected as much from you, Tagore, you fought alongside Angron from the last days of the War Hounds, ever since Desh’ea, but what about you two?’ asked Atharva, nodding towards Asubha and Subha. ‘Neither of you have yet been augmented like Tagore. What do you say?’

‘I agree with Tagore,’ said Subha, an answer Atharva had expected.

‘And you?’

Subha’s twin met Atharva’s unblinking stare with one of his own. His face was thoughtful, measured, and Atharva liked that he took time to consider the question properly.

‘I believe we do not have enough facts to make a decision as important as this,’ he said.

‘A coward’s answer,’ snapped Tagore, and Atharva saw the undercurrent of anger in Asubha’s face. Tagore was his sergeant and deserved his respect, but they were far from the strictures of their Legion, and it was never wise to use such pejorative words amongst warriors of such notorious violence.

‘You mistake prudence for cowardice, Tagore,’ said Asubha. ‘It may be that Horus Lupercal and our primarchs have just cause for rebellion, but Atharva speaks truly when he says that none of us know our Legions any more. Perhaps they have fallen to petty jealousies or allowed ambition to blind them to their oaths of loyalty, who can say?’

‘Loyalty is all I need,’ said Subha, moving away from his brother. ‘I will find a way to rejoin the Legion and fight by my primarch’s side.’

‘Spoken like a true World Eater,’ said Tagore, clapping a hand on Subha’s shoulder. ‘We should all rejoin our Legions. If you want to stay on Terra, Atharva, that is your business, but I will find a way to return to my primarch. I have my strength and battle brothers to guard my flanks. I willfind a way off Terra. It may be that I will walk the Crimson Path before I get to Isstvan V, but this is a road I intend to travel.’

‘And what then?’ asked Atharva. ‘What if you manage to reach Angron’s side only to discover he is a corrupt traitor who does not deserve your loyalty?’

‘Then I will take up my sword and die trying to kill him.’

‘ARE YOU HEARING all this?’ asks Saturnalia. ‘The madness of it astounds me.’

‘I hear it,’ says Nagasena, ‘and the sadness of it almost breaks my heart.’

Saturnalia looks up at him, unable to read his face, and Nagasena knows he is trying to decide whether he is joking or being disloyal.

‘Choose your words carefully, hunter,’ says the giant Custodian, ‘lest you find yourself dragged back to Khangba Marwu alongside these traitors.’

‘You misunderstand me, friend Saturnalia,’ says Nagasena. ‘I will hunt these men until the ends of Terra. Without mercy and without pause, but to hear their fear and confusion is to know that, but for an accident of genetics, they could have fought at our side. They are lost and do not know what to do.’

‘I don’t know what feed you were listening to,’ says Golovko, looking up from the data slate carried by Kartono. ‘but I heard them say that they were going to try and get off-world to rejoin their Legions. We have to stop them.’

‘Agreed,’ replies Nagasena with a nod, staring hard into the grainy image flickering on the data slate. The signal is weak and distorted by all the metal and illegal antennae that cluster like wire-weed on the roofs of nearby buildings, but it is clear enough to give the hunters their first glimpse of their quarry.

Behind Nagasena, the burned remains of the Cargo 9smoulders in the purple glow of evening, surrounded by Black Sentinels with their weapons primed and held to their shoulders. Night is drawing in, and the Petitioner’s City is a dangerous place in darkness, but they have no choice but to continue onwards. Much of the shuttle has been picked clean by scavengers, its wings cut free with acetylene torches and the metal ribs of its internal structure stripped to form supporting columns or girders.

Some of the salvagers fought them, believing them to be rivals for these valuable parts, but they are now dead, shot down by the Black Sentinels as they swept in from the landing site, two hundred metres back. Saturnalia and Golovko wasted valuable time in searching the wreckage, but Nagasena knew they would find nothing.

Severian had made sure of that, and Nagasena knows he will be the most formidable of the renegades to catch. That one is a wolf, a loner who will not hesitate to abandon his fellows when he feels the breath of the hunters at his neck. Adept Hiriko stands by the crushed fuselage, running her palm over the warm metal and attempting to draw out any latent psi-traces of their targets. It is a hopeless task. Too many have travelled in this craft and too many have touched it since it crashed for any real trace to be left, but every avenue must be explored, every element considered.

Saturnalia is impatient to begin the hunt again, but Nagasena knows their prey is not going anywhere in the immediate future, and there is much that can be learned by simply observing them for a time. While the escaped Space Marines debate their future, unaware that their every move is being watched – thanks to the coerced co-operation of House Castana and Kartono’s technical ability – they will gradually reveal their strengths and weaknesses, making the hunt’s outcome inevitable. It is the way Nagasena trained to hunt, the way he has worked for many years, and no amount of pressure from Saturnalia or Golovko will change that.

Saturnalia turns to Kartono, his manner brusque and irritated.

‘Can you identify their location from this feed?’

Kartono looks over at Nagasena, and nods slowly before answering. ‘Not precisely, but maybe to within a few hundred metres.’

Saturnalia then addresses Athena Diyos. ‘And if you are that close, can you establish a more precise location?’

Athena Diyos does not want to be here, but she knows she has little choice. From what Nagasena has learned of her, he knows her to be an unforgiving tutor, but a staunch friend of those who earn her trust. It is not hard to see why she should feel protective of Kai Zulane.

‘I think so,’ she says.

‘Then we need to move,’ says the Custodian.

Nagasena steps to Saturnalia, blocking his path. ‘Be mindful, Custodian,’ he says. ‘This is my hunt, and I set the pace. You underestimate these men at your peril. In any scenario they are dangerous beyond belief. Corner them and they will fight like Thunder Warriors of old.’

‘There’s only seven of them, and I doubt the Death Guard will see the sunrise,’ sneers Golovko. ‘Throne only knows what you think you gain by waiting.’

‘I gain understanding of the truth,’ says Nagasena, resting his right hand on the pommel stone of his sword. ‘And that is the most important thing.’

‘Truth?’ asks Saturnalia. ‘What truth do you think to learn from traitors?’

Nagasena hesitates before answering, but he will not lie to Saturnalia, for a lie would diminish him.

‘I hope to learn whether I should catch these men at all,’ he says.

KAI WOKE FROM a terrible dream in which his head was being slowly encased in clay that hardened around him with each breath. Like being bricked up in a suffocating cave the exact dimensions of his body, each breath came shorter and more forced than the last. As awareness of his surroundings returned to Kai, his fatigue crashed down upon him as though he had not rested at all.

His eyes hurt and he rubbed the skin around them. His skull felt as though it was vibrating from the inside, and the interrogation clamps that had widened the orbits of his eye sockets to allow the insertion of ocular-recording equipment had badly bruised his cheeks and forehead. He scratched his eyes, feeling like there was an itch beneath his skin he couldn’t reach.

Kai felt the eyes of the Outcast Dead upon him and took a deep breath as he saw the sky beyond the entrance of their hiding place was a yellowed purple, like an intensely livid bruise.

‘What’s happening?’ he asked, sensing the tension in the warriors before him. ‘Are we in trouble?’

Severian chuckled and the World Eaters grinned broadly.

‘We are branded as traitors and are being hunted by our enemies,’ said Tagore. ‘It’s fair to say we are going to be in trouble for some time.’

‘That’s not what I meant,’ said Kai.

‘We are deciding what is to be done with you,’ said Atharva, and Kai felt a tremor of fear at the casual nature of his words.

‘Oh,’ he said, scratching the skin beneath his eyes. ‘Did you reach a decision?’

‘Not yet,’ admitted Atharva. ‘Some of our number want to escape Terra and take you to Horus Lupercal, while others want to just kill you.’

‘Kill me? Why?’ gasped Kai.

‘You represent a very real danger, Kai,’ said Kiron, putting a hand on his shoulder, and Kai felt the killing power in that grip. The Space Marine’s hand was so enormous it cupped his entire shoulder, from clavicle to scapula. With only the slightest increase of pressure, Kiron could break every bone without even thinking about it.

‘Danger, what danger?’

‘I suspect the information you carry is knowledge of the future,’ said Atharva. ‘And truth is the most dangerous weapon in any war.’

‘But I don’t know anything,’ protested Kai. ‘I told them that!’

‘You do,’ said Kiron, pressing hard enough to make Kai wince in pain. ‘You just don’t know you do. The army that carries truth as its banner cannot falter. Picture a perfect war, waged by warriors who know they cannot lose. That is the promise you carry within you, and to possess that knowledge, great and good men will do anything to make you their banner.’

‘We will fight our way off this world, and you will help us,’ said Tagore.

‘Leave Terra?’ said Kai, baring his teeth and rubbing his temples with the heels of his palms. ‘Throne, it feels like my eyes are on fire.’

‘What is wrong with him?’ asked Subha.

Asubha knelt beside Kai and took his head in his hands. The World Eater turned Kai’s head and peeled back the skin at the juncture of his augmetics. A tear of blood ran down Kai’s cheek.

‘Angron’s blood,’ swore Asubha. ‘Be silent all of you, they are watching and listening.’

Kai struggled in the World Eater’s grip, but it was utterly implacable. He could no more move his head than he could move his shoulder. Asubha stared straight into Kai’s eyes and had he been able to move, he would have flinched at the venom he saw there.

‘Clever,’ said Asubha, resting his fingertips on Kai’s cheeks, ‘but this is where it ends.’

‘What are you talking about?’ gasped Kai.

‘What are you doing?’ said Atharva.

‘Covering our trail,’ said Asubha, digging his thumbs into the meat of Kai’s skull and gouging out his eyes in a welter of blood and cabling.