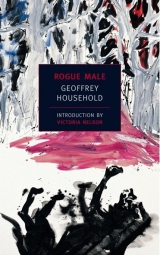

Текст книги "Rogue Male "

Автор книги: Geoffrey Household

Жанр:

Триллеры

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 12 страниц)

I pretended I had forgotten something, and shot out of the exit, up the stairs and down a corridor to the north-bound platform. No train was in. Even if there had been a train, the Major was too close behind for me to catch it and leave him standing.

I noticed that the shuttle train at the Aldwych left from the opposite side of the same platform. This offered a way of escape if ever there were two trains in at the same time.

The escalator took me back to the Central London level. The bird-man was talking to the chap in a glass-box at the junction of all the runways. I’d call him a ticket-collector but he never seems to collect any tickets; probably he is there to answer silly questions such as the bird-man was busily engaged in asking. I took the second escalator to the surface, and promptly dashed down again.

The bird-man followed me, but a bit late. We passed each other about midway, he going up and I going down and both running like hell. I thought I had him, that I could reach a Central London train before he could; but he was taking no risks. He vaulted over the division on to the stationary staircase. We reached the bottom separated only by the extra speed of my moving staircase—and that was a mere ten yards. The man in the glassbox came to life and said: ‘’Ere! You can’t do that, you know!’ But that didn’t worry the bird-man. He was content to remain and discuss his anti-social action with the ticket-non-collector. I had already turned to the right into the Piccadilly Line and on to Major Quive-Smith’s preserves.

At the bottom of the Piccadilly escalator you turn left for the north-bound trains, and continue straight on for the west-bound. To the right is the exit, along which an old lady with two side parcels was perversely trying to force her way against the stream of outcoming passengers. Major Quive-Smith was away to the left, at the mouth of the passage to the north-bound trains; so I plunged into the stream after the old lady, and was clear of it long before he was.

I ran on to the north-bound platform. An Aldwych shuttle was just pulling in, but there was no Piccadilly train. I shot under the Aldwych line, down to the west-bound platform, into the general exit, jamming him in another stream of outcoming passengers, and back to the north-bound Piccadilly. There was a train standing, and the Aldwych shuttle had not left. I jumped into the Piccadilly train with the Major so far behind that he was compelled to enter another coach just as the doors were closing and just as I stepped out again. Having thus despatched the Major to an unknown destination, I got into the Aldwych shuttle, which at once left on its half-mile journey.

This was all done at such a pace that I hadn’t had time to think. I ought to have crossed to the west-bound Piccadilly and taken a train into the blue. But, naturally enough, I wanted to leave Holborn station as rapidly as possible, for fear of running into the bird-man or another unknown watcher if I waited. After half a minute in the Aldwych shuttle I realized that I had panicked like a rabbit in a warren. The mere couple of ferrets who had been after me had been magnified by my escape mechanism—a literal escape mechanism this, and working much faster than my mind—into an infinity of ferrets.

When we arrived at the Aldwych station and I was strolling to the lifts, I saw that it was not yet too late to return to Holborn. The bird-man would still be on the Central London level, for he might lose me if he left it for a moment. Quive-Smith couldn’t have had time to telephone to anyone what had happened.

I turned back and re-entered the shuttle. The passengers were already seated in the single coach, and the platform clear; but a man in a black hat and blue flannel suit got in after me. That meant that he had turned back when I had turned back.

At Holborn I remained seated to prove whether my suspicions were correct. They were. Black Hat got out, sauntered around the platform, and got in again just before the doors closed. They had been far too clever for me! They had evidently ordered Black Hat to travel back and forth between Holborn and the Aldwych, and to go on travelling until either I entered that cursed coach or they gave him the signal that I had left by some other route. All I had done was to send Quive-Smith to Bloomsbury, whence no doubt he had already taken a taxi to some central clearing-point to which all news of my movements was telephoned.

As we left again for Aldwych, Black Hat was at the back of the coach and I was in the front. We sat as far away as possible from each other. Though we were both potential murderers, we felt, I suppose, mutual embarrassment. Mutual. I wish to God he had sat opposite me, or shown himself in some way less human than I.

The Aldwych station is a dead end. A passenger cannot leave it except by the lift or the emergency spiral staircase. Nevertheless I thought I had a wild chance of getting away. When the doors of the train opened, I dashed on to and off the platform, round a corner to the left and up a few stairs; but instead of going ten yards farther, round to the right and so to the lift, I hopped into a little blank alley that I had noticed on my earlier walk.

There was no cover of any sort, but Black Hat did just what I hoped. He came haring up the corridor, pushing through the passengers with his eyes fixed straight ahead, and jumped for the emergency staircase. The ticket collector called him back. He shouted a question whether anyone had gone up the stairs. The ticket collector, in turn, asked was it likely. Black Hat then entered the lift, and in the time it took him to get there and to glance over the passengers I was out of my alley and back on the platform.

The train was still in, but if I could catch it, so could Black Hat. The corridor was short, though with two right-angled twists, and he couldn’t be more than five seconds behind me. I jumped on to the line and took refuge in the tunnel. There wasn’t any employee of the Underground to see me except the driver, and he was in his box at the front of the coach. The platform of course, was empty.

Beyond the Aldwych station there seemed to be some fifty yards of straight tube, and then a curve, its walls faintly visible in a gleam of grey light. Where the tunnel goes, or if it ends in an odd shaft after the curve, I didn’t have time to find out.

Black Hat looked through the coach and saw that I wasn’t in it. The train pulled out, and when its roar had died away there was absolute silence. I hadn’t realized that Black Hat and I would be left alone a hundred feet under London. I lay flattened against the wall in the darkest section of the tunnel.

The working of the Aldwych station is very simple. Just before the shuttle is due, the lift comes down. The departing passengers get into the train; the arriving passengers get into the lift. When the lift goes up and the train leaves, Aldwych station is as deserted as an ancient mine. You can hear the drip of water and the beat of your heart.

I can still hear them, and the sound of steps and his scream and the hideous, because domestic, sound of sizzling. They echoed along that tunnel which leads Lord knows where. A queer place for a soul to find itself adrift.

It was self-defence. He had a flash-light and a pistol. I don’t know if he meant to use it. Perhaps he was only as frightened of me as I was of him. I crawled right to his feet and sprang at him. By God, I want to die in the open! If ever I have land again, I swear I’ll never kill a creature below ground.

I lifted the bandages from my head and put them in my pocket; that expanse of white below my hat attracted too much attention to me. Then I came out, crossed the platform into the corridor, and climbed a turn of the emergency stairs. As soon as the lift came down, I mingled with the departing passengers and waited for the train. When it came in, I went up in the lift with the new arrivals. I gave up my shilling ticket and received a surprised glance from the collector since the fare from Holborn was but a penny. The only alternative was to pretend I had lost my ticket and to pay; that would have meant still closer examination. I left the station free, unwatched, unhurried, and took a bus back to the respectable squares of Kensington. Who would look for a fugitive between the Cromwell and Fulham roads? I dined at leisure, and then went to a cinema to think.

In these days of visas and identification cards it is impossible to travel without leaving a trail that can, with patience, bribery, and access to public records, be picked up. In the happy years between 1925 and 1930 you could talk yourself over any western European frontier, so long as you looked respectable and explained your movements and business with a few details that could be checked; you could treat frontier police as men of decency and common sense: two virtues that they could then afford to indulge. But now unless a traveller has some organization—subversive or benevolent—to help him, frontiers are an efficient bar to those who find it inconvenient or impossible to show their papers; and even if a frontier be crossed without record, there isn’t the remotest village where a man can live without justifying himself and his reasons for being himself. Thus Europe, for me, was a mere trap with a delayed action.

Where, then, could I go? I thought at once of a job on a ship, for there’s a shortage of seamen in these days; but it wasn’t worth visiting shipping offices with my hands in the state they were. Rule out a long voyage as a stowaway. Rule out a discreet passage on a cargo ship. I could easily have got such a passage, but only by revealing my identity and presence in England to some friend. That I wanted to avoid at all costs. Only Saul, Peale, Vaner, and the admirable secret service which was hunting me knew that I wasn’t in Poland. None of them would talk.

There remained a voyage in a passenger vessel. I could certainly get on to the ship without showing my passport; I might be able to get off it. But passenger lists are open to inspection, and if my name appeared on one some blasted reporter would consider it news and save my hunters trouble. They would, any way, be watching the lists themselves.

Then I needed a false passport. In normal circumstances I have no doubt that Saul or my friends in the Foreign Office could have arranged some tactful documentation for me, but, as it was, I could not involve any of them. It was unthinkable, just as police protection was unthinkable. I could not risk embarrassing the officials of my country. If the extraordinary being at whose waistcoat I had looked through a telescopic sight were moved by his daemon or digestion to poison international relations more than they already were, a very pretty case could be built up against a government that helped me to escape.

As I sat back in that cheap cinema seat, with my eyes closed and with the meaningless noises and music forcing my mind from plan to plan, I saw that I could only disappear by not leaving England at all. I must bury myself in some farm or country pub until the search for me had slackened.

When the main feature, as I believe they call it, was at its most dramatic quarter of an hour and the lavatory was likely to be empty, I left my seat, bathed my eye with the lotion the doctor had given me, and put on my bandages again. Then I wandered westwards through the quiet squares which smelled of a London August night—that perfume of dust and heavy flowers, held down by trees into the warm, well-dug ravines between the houses.

I decided against sleeping at a hotel. My position was becoming so complicated that it seemed wise to occupy neutral territory whence I could move according to circumstances. A hotel porter might compel me into some act or lie that was unnecessary. I took a bus to Wimbledon Common; I had never been there, but knew there was a golf course and some sort of cover where corpses were very frequently discovered—indications of a considerable stretch of country that was open to the public at night.

The Common turned out to be ideal. I spent the night in a grove of silver birch where the fine soil—silver, too, it seemed to me, but the cause was probably the half-moon—held the heat of the day. There is, for me, no better resting-place than the temperate forests of Europe. Can one reasonably speak of forest at half an hour from Piccadilly Circus? I think so. The trees and heath are there, and at night one sees no paper bags.

In the morning I brushed off the leaves and bought a paper in a hurry from the local tobacconist as if I were briskly on my way to the City. In my new and too smart clothes I looked the part. ALDWYCH MYSTERY was occupying half a column of the centre page. I retired to a seat on the Common before committing myself to further dealings with the public.

The body had been discovered almost as soon as I was clear of the station. Foul play, said the paper cautiously, was suspected. In other words, the police were wondering how a man who had fallen on his back across the live rail could have suffered a smashing blow in the solar plexus.

The deceased had been identified. He was a Mr Johns who lived in a furnished room in those barrack squares of furnished rooms between Millbank and Victoria Station. His age, his friends, his background were unknown (and, if he knew his job always would be), but the paper carried an interview with his landlady. It must have been a horrible shock to be knocked up by a reporter around midnight and told that her lodger had been killed under suspicious circumstances. Or perhaps not. I have been assured by newspapermen that even close relatives forget their grief in the excitement of getting into the news; so a landlady, provided she had her rent, might not worry overmuch. Though knowing nothing whatever about the man under her roof, she had been most communicative. She said:

‘He was a real gentlemen and I’m sure I don’t know why anyone should have done him harm. His poor old mother will be broken-hearted.’

But it appeared that nobody had discovered the address of the poor old mother. The only evidence for her existence was the landlady’s statement that she would often telephone Mr Johns, who thereupon rushed out in a great hurry to see her. I was not, of course, so cynical at the moment; but when the aged mother, such jam for journalists, was not mentioned at all in the evening papers, my conscience was easier.

The police were anxious to interview a well-dressed clean-shaven man in the early forties, with a bruised and blackened eye, who was observed to leave the Aldwych station shortly before the body was discovered, and surrendered a shilling ticket to the collector. I am not yet forty and I was not well dressed, but the description was accurate enough to be unpleasant reading.

It might have been worse. If they had wanted a man with a bandaged head, one of Saul’s clerks might have let information leak, and the taxi-driver, who had, no doubt, already answered a number of mysterious questions, would have gone to the police. As it was, the public were left with the impression that the man’s eye had been injured in the struggle below ground. No one except Saul and Mr Vaner could suspect that I might be the man concerned. Both of them would assume that the rights and wrongs were for my own conscience to settle rather than the police.

That confounded eye finished any chance I might have had of living in some obscure farm or inn. A wanted man with any well-marked peculiarity cannot hide in an English village. The local bobby has nothing to do but see that the pubs observe a decent discretion, if not the law, and that farmers do not too flagrantly ignore the mass of paperasserie that they are supposed to have read and haven’t. He pushes his bicycle up the hills, dreaming of catching a real criminal, and when the usual chap with a scar or with a finger missing is wanted by the metropolitan police, every person of small means who has recently retired to a cottage (which puts him under suspicion anyway) is visited by the village bobby at unexpected times on the most improbable errands.

There was nothing for it but to live in the open. I sat on my bench on Wimbledon Common and considered what part of England to choose. The north was the wilder, but since I might have to endure a winter, the rigour of the climate was not inviting. My own county, though I carried the ordnance map in my eye and knew a dozen spots where I could go to ground, had to be avoided. I wonder what my tenants made of the gentleman who, at that time, was doubtless staying at the Red Lion, asking questions, and describing himself as a hiker who had fallen in love with the village. A hideous word—hiker. It has nothing to do with the gentle souls of my youth who wandered in tweeds and stout shoes from pub to pub. But, by God, it fits those bawling English-women whose tight shorts and loose voices are turning every beauty spot in Europe into a Skegness holiday camp.

I chose southern England, with a strong preference for Dorset. It is a remote county, lying as it does between Hampshire, which is becoming an outer suburb, and Devon which is a playground. I knew one part of the county very well indeed, and, better still, there was no reason for anyone to suppose that I knew it. I had never hunted with the Cattistock. I had no intimate friends nearer than Somerset. The business that had taken me to Dorset was so precious that I kept it to myself.

There are times when I am no more self-conscious than a chimpanzee. I had chosen my destination to within ten yards; yet, that day, I couldn’t have told even Saul where I was going. This habit of thinking about myself and my motives has grown upon me only recently. In this confession I have forced myself to analyse; when I write that I did this because of that, it is true. At the time of the action, however, it was not always true; my reasons were insistent but frequently obscure.

Though the precise spot where I was going was no more nor less present in my consciousness than the dark shadows which floated before my left eye, I knew I had to have a fleece-lined, waterproof sleeping-bag. I dared not return to the centre of London, so I decided to telephone and have the thing sent COD to Wimbledon station by a commissionaire.

I spoke to the shop in what I believed to be a fine disguised bass voice, but the senior partner recognized me almost at once. Either I gave myself away by showing too much knowledge of his stock, or my sentence rhythm is unmistakable.

‘Another trip, sir, I suppose?’

I could imagine him rubbing his hands with satisfaction at my continued custom.

He mentioned my name six times in one minute of ejaculations. He burbled like a fatherly butler receiving the prodigal son.

I had to think quickly. To deny my identity would evidently cause a greater mystery than to admit it. I felt pretty safe with him. He was one of the few dozen blackcoated archbishop-like tradesmen of the West End—tailors, gunsmiths, bootmakers, hatters—who would die of shame rather than betray the confidence of a customer, to whom neither the law nor the certainty of a bad debt is as anything compared to the pride of serving the aristocracy.

‘Can anyone hear you?’ I asked him.

I thought he was probably chucking my name about for the benefit of a shop assistant or a customer. These ecclesiasts of Savile Row and Jermyn Street are about the only true dyed-in-the-wool snobs that are left.

He hesitated an instant. I imagined him looking round. I knew the telephone was in the office at the far end of the shop.

‘No, sir,’ he said with a shade of regret that made me certain he was telling the truth.

I explained to him that I wished no one to know I was in England and that I trusted him to keep my name off his lips and out of his books. He oozed dutifulness—and thoughtfulness too, for after much humming and hawing and excusing himself he asked me if I would like him to bring me some cash together with the sleeping-bag. I very possibly had not wished to visit my bank, he said. Wonderful fellow! He assumed without any misgiving at all that his discretion was greater than that of my bank manager. I wouldn’t be surprised if it was.

Since I was in for it anyway, I gave him a full list of my requirements—a boy’s catapult, a billhook, and the best knife he had; toilet requisites and a rubber basin; a Primus stove and a pan; flannel shirts, heavy trousers and underclothes, and a wind-proof jacket. Within an hour he was at Wimbledon station in person, with the whole lot neatly strapped into the sleeping-bag. I should have liked a firearm of some sort, but it was laying unfair weight on his discretion to ask him not to register or report the sale.

I took a train to Guildford, and thence by slow stages to Dorchester, where I arrived about five in the afternoon. I changed after Salisbury, where a friendly porter heaved my roll into an empty carriage on a stopping train without any corridor. By the time we reached the next station I was no longer the well-dressed man. I had become a holiday-maker with Mr Vaner’s very large and dark sun-glasses.

I left my kit at Dorchester station. What transport to take into the green depths of Dorset I hadn’t the faintest notion. I couldn’t buy a motor vehicle or a horse because of the difficulty of getting rid of them. A derelict car or a wandering horse at once arouses any amount of enquiry. To walk with my unwieldy roll was nearly impossible. To take a bus merely puts off the moment when I would have to find more private conveyance.

Strolling as far as the Roman amphitheatre, I lay on the outer grass slope to watch the traffic on the Weymouth road and hope for an idea. The troops of cyclists interested me. I hadn’t ridden a cycle since I was a boy, and had forgotten its possibilities. These holiday-makers carried enough gear on their backs and mudguards to last a week or two, but I didn’t see how I could balance my own camping outfit on a bike.

I waited for an hour, and along came the very vehicle I wanted. I have since noticed that they are quite common on the roads, but this was the first I had seen. A tandem bicycle it was, with pa and ma riding and the baby slung alongside in a little side-car. I should never have dared to carry any offspring of mine in a contraption like that, but I must admit that for a young couple with no nerves and little money it was a sensible way of taking a holiday.

I stood up and yelled to them, pointing frantically at nothing in particular. They dismounted, looked at me with surprise, then at baby, then at the back-wheel.

‘Sorry to stop you,’ I said. ‘But might I ask you where you bought that thing? Just what I want for me and the missus and the young ’un!’

I thought that struck the right note.

‘I made it,’ said pa proudly.

He was a boy of about twenty-three or -four. He had the perfect self-possession and merry eyes of a craftsman. One can usually spot them, this new generation of craftsmen. They know the world is theirs, and are equally contemptuous of the professed radical and the genteel. They definitely belong in Class X, though I suppose they must learn to speak the part before being recognized by so conservative a nation.

‘Are you in the cycle trade?’

‘Not me!’ he answered with marked scorn for his present method of transport. ‘Aircraft!’

I should have guessed it. The aluminium plating and the curved, beautifully tooled ribs had the professional touch; and two projections at the front of the side-car, which at first glance I had taken for lamps, were obviously model machine-guns. I hope they were for pa’s amusement rather than for the infant’s.

‘He looks pretty comfortable,’ I said to the wife.

She was a sturdy wench in corduroy shorts no longer than bum-bags, and with legs so red that the golden hairs showed as continuous fur. Not my taste at all. But my taste is far from eugenic.

‘’E loves it, don’t you, duck?’

She drew him from the side-car as if uncorking a fat puppy from a riding-boot. I take it that she did not get hold of him by the scruff of the neck, but my memory insists that she did. The baby chortled with joy, and made a grab for my dark glasses.

‘Now, Rodney, leave the poor gentleman alone!’ said his mother.

That was fine. There was a note of Pity the Blind about her voice. Mr Vaner’s glasses had no delicate tints. They turned the world dark blue.

‘You wouldn’t like to sell it, I suppose?’ I asked, handing pa a cigarette.

‘I might when we get home,’ he answered cautiously. ‘But my home’s Leicester.’

I said I was ready to make him an offer for bicycle and side-car then and there.

‘And give up my holiday?’ he laughed. ‘Not likely, mister!’

‘Well, what would it cost?’

‘I wouldn’t let it go a penny under fifteen quid!’

‘I might go to twelve pounds ten,’ I offered—I’d have gladly offered him fifty for it, but I had to avoid suspicion. ‘I expect I could buy the whole thing new for that, but I like your side-car and the way it’s fixed. My wife is a bit nervous, you see, and she’d never put the nipper in anything that didn’t look strong.’

‘It is strong,’ he said. ‘And fifteen quid would be my last word. But I can’t sell it you, because what would we do?’

He hesitated and seemed to be summing up me and the bargain. A fine, quick-witted mind he had. Most people would be far too conservative to consider changing a holiday in the middle.

‘Haven’t anything you’d like to swap?’ he asked. ‘An old car or rooms at the seaside? We’d like a bit of beach to sit on, but what with doctor’s bills and the missus so extravagant …’

He gave me a broad wink, but the missus wasn’t to be drawn.

‘He’s one for kidding!’ she informed me happily.

‘I’ve got a beach hut near Weymouth,’ I said. ‘I’ll let you have it free for a fortnight, and ten quid for the combination.’

The missus gave a squeal of joy, and was sternly frowned upon by her husband.

‘I don’t know as I want a beach hut,’ he said, ‘and it would be twelve quid. Now we’re going to Weymouth tonight. Now suppose we did a swap, could we move in right away?’

I told him he certainly could, so long as I could get there ahead of him to fix things up and have the place ready. I said I would see if there were a train.

‘Oh, ask for a lift!’ he said, as if it were the obvious way of travelling any short distance. ‘I’ll soon get you one.’

That chap must have had some private countersign to the freemasonry of the road. Myself, I never have the impudence to stop a car on a main road. Why, I don’t know. I’m always perfectly willing to give a lift if I am driving.

He let half a dozen cars go by, remarking ‘toffs!’, and then stopped one unerringly. It was a battered Morris, very much occupied by a sporty-looking gent who might have been a bookmaker or a publican. He turned out to be an employee of the County Council whose job it was to inspect the steamrollers.

‘Hey, mister! Can you give my pal a lift to Weymouth?’

‘Look sharp, then!’ answered the driver cheerily.

I arranged to meet the family at the station at seven-thirty, and got in.

He did the eight miles to Weymouth in a quarter of an hour. I explained that I was hopping on ahead to get rooms for the rest of our cycling party when they arrived, and asked him if he knew of any beach huts for rent. He said there weren’t any beach huts, and that, what was more, we should find it difficult to get rooms.

‘A wonderful season!’ he said. ‘Sleeping on the beach they were at Bank Holiday!’

This was depressing. I had evidently been rash in my offer for the family combination. I told him that I personally intended to stay some time in Weymouth, and what about a tent or a bungalow or even one of those caravans the steamroller men slept in?

That amused him like anything.

‘Ho!’ he said. ‘They’re county property, they are! They wouldn’t let you have one of them things. But I tell you what!’—he lowered his voice confidentially in the manner of the English when they are proposing a deal (it comes, I think, from the national habit of buying and selling in a public bar)—‘I know a trailer you could buy cheap, if you were thinking of buying, that is.’

He drove me to a garage kept by some in-law of his, where there was a whacking great trailer standing in the yard amid a heap of scrap-iron. It appeared home-made by some enthusiast who had forgotten, in his passion for roominess and gadgets, that it had to be towed round corners behind a car. The in-law and the steam-roller man showed me over that trailer as if they were a couple of high-powered estate agents selling a mansion. It was a little home from home, they said. And it was! It had everything for two except the bedding, and it was mine for forty quid. I accepted their price on condition that they threw in the bedding and a cot for Rodney, and towed me then and there to a camp-site. They drove me a couple of miles to the east of Weymouth where there was an open field with a dozen tents and trailers. I rented a site for six months from the landowner and told him that friends would be occupying the trailer for the moment, and that I myself hoped to get down for many weekends in the autumn. He showed no curiosity whatever; if strange beings chose to camp on his land he collected five bob a week from them in advance and never went near them again.

When we got back to the town, I had a quick drink with my saviours and vanished. It was nearly eight before I could reach the station. Pa and ma were leaning disconsolately against the railings.

‘Now then, mister,’ said my aircraft mechanic, ‘time’s money, and how about it?’

He was a little peeved at my being late. Evidently he had been thinking the luck too good to be true, and that he wouldn’t see me again.

We walked wearily out to the camp-site. The trailer was quite enchanting in the gathering dusk, and I damn near gave it to them. Well, at any rate he got his fortnight’s holiday rent-free, and I expect he managed to replace tandem and side-car for the twelve quid. I said that I should probably be back before the end of his fortnight, but that, if I was not, he should give the key to the landowner. I don’t think the trailer can be the object of any enquiry until the six months are up; and by that time I hope to be out of England.