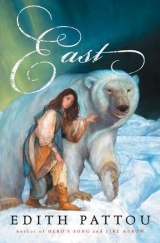

Текст книги "East "

Автор книги: Эдит Патту

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

White Bear

Glowing.

The moon through a doorway.

Breath hard in my throat.

Heart full to burst.

The moon through a doorway.

And in its light...

Hope.

Neddy

WHEN FATHER RETURNED from his journey, he told me of his exhausting, disappointing search, and also of the one little glimmer of hope. A sighting by a drunken fool was too pitiful to pin one's hopes to, but we both did anyway.

In the meantime, we were just beginning to experience the fruits of our newfound good fortune. The "journey maps" that Soren had thought so promising turned out to be vastly successful, exceeding even his expectations. Demand for more, with increased routings, came pouring in. My brother and sister and I were put in charge of drafting new maps based on the new charts Father had brought back. Father supervised us, until it was time for him to leave again. Between that work and watching over the farm, I barely had time to look at the books Soren had so kindly sent to me.

I noticed that in Father's absence Mother was becoming even more superstitious than before. In part this was because Father wasn't there to temper her, but I also believe that because in some way—either small or large, depending on your point of view—it was Mother's superstition that had caused us to lose Rose, she had to justify herself. If it was superstition that lost Rose, then superstition would also bring her back. At least that was my best guess as to why Mother was behaving the way she did.

I also noticed, as we all did, that Mother had suddenly gotten quite chummy with Widow Hautzig. The unpleasant woman had come nosing around when she got wind of our reversal in fortune, and we were all mystified at first by the burgeoning friendship until we discovered that Widow Hautzig was also very superstitious. Rose had commented on this to me once or twice, but I had paid little attention. Also, Mother had found an herbal remedy for rheumatism that Widow Hautzig swore by, and this, too, tightened their bond.

I overheard them one day going on about some charm worn around the ankle that would direct a person to that which was lost. I thought I heard the old widow whisper Rose's name, and I saw Mother shake her head with a sidelong glance at me. I wondered then just how much Mother may have confided in Widow Hautzig, and the thought made me uncomfortable.

Father returned from his most recent journey, but this time he had not even a kernel of hope to offer. He seemed tired and out of sorts. And not long after his arrival home, I came across Mother and Father quarreling. She was urging him to tie the herbal charm around his ankle when he set off on his next journey to seek Rose. Father's face was pale and his tone was tight, as if from the strain of holding in a great rage. "I want none of your charms, Eugenia. It was your foolish superstition that led us down this road and I'll have none of it. Not ever again, do you hear!" And he stalked away.

The look on Mother's face at first made me want to comfort her, for she seemed confused and unhappy, even a little lost. But then I saw her give a shrug, and her features resolved into a placid, comfortable expression. And instead of comforting her, I, too, walked away.

There was money by then to make improvements to the farmhouse, and Mother enjoyed the choosing and spending, though she tried not to show it too much. We were all aware, every minute of every day, of that which was lost to us, and no amount of comfort or wealth would make up for that.

One of the first purchases Mother made was the loom owned by Widow Hautzig, the one that we had repaired. (It seemed to me that the least the widow could have done was to give that loom as a gift to us, especially because we had been the ones to restore it to working order, but despite her close friendship with Mother, the widow was as grasping as ever.) Mother cleaned and polished the loom, and set it in a place of honor in our great room, where it awaited Rose's return.

Widow Hautzig took to accompanying Mother on her occasional shopping trips into Andalsnes. They spent much of their time at a shop run by Sikram Ralatt, a traveling merchant who had recently come to Andalsnes. He sold various concoctions and herbal remedies, as well as a whole line of charms promising one outcome or another. As I said, Father was either traveling or working in his new workshop, and paid little heed to what Mother was doing. But I saw and was uneasy.

Rose

I SET TO WORK ON a dress of plain gray wool, and the feel of the coarse thread settled me. I had hung the dresses of silver, gold, and moon in a large cupboard in my room, where I kept my own few items of clothing. But every night before bed, I would see those extravagant gowns lined up in a row and I would flush with embarrassment. I kept reminding myself I had made them to sell but didn't really believe it.

One evening I could no longer stand looking at them and decided to pack the dresses away, ready for taking with me if I—no, when I—left there. Though I wouldn't have dreamed of taking anything else from the castle, like a book or a fine bowl, for some reason I didn't think twice about taking the gowns away with me. The way I looked at it was, taking something that already had been there when I arrived was the same as stealing, but I had created the dresses myself, and the materials I used ... Well, those were little enough payment for my lost freedom.

Taking the silver gown over to the bed, I carefully began folding it. The gowns were not small, with their large floor-length skirts. I would need something much bigger than my little knapsack from home to carry the dresses in. But a curious thing happened while I folded. The gossamer fabric compacted, even seemed to shrink in on itself, and with each fold it got smaller and smaller. I kept folding, amazed by the strange properties of the fabric, until I was left with a small square that fit into the palm of my hand. I stared at the small silver packet, unbelieving. And yet there it was.

I became suddenly worried that something had happened to the dress, that it had been crushed and compacted beyond wearing, so I unfolded it. And the reverse occurred. When I was done the dress shook out beautifully, unwrinkled and intact. So I folded it all over again, and did the same with the golden gown. It, too, folded neatly into a small square. As did the moon dress.

I looked at the three small packets lying on the bed, wondering if they would fit into the leather wallet I had brought with me. Neddy had made it, and because I had no money, it held a small sewing kit with needles, pins, and several kinds of thread.

I retrieved the wallet from my bag and, taking out the sewing kit, slipped the folded dresses into it. They fit perfectly, as if the wallet had been designed for storing them. I stowed the full wallet in my bag, which I placed back in the cupboard.

The gray dress was quickly finished, although working on it was quite boring in contrast to creating the three gowns. Then, in quick succession, I produced thick woolen stockings, woolen mittens, and a hat and scarf, all out of the same gray wool. Making those sturdy garments was like returning to a diet of hard bread and water after overindulging in the likes of champagne and cream-filled cakes. Bland and dull that "diet" may have been, but it steadied me and I was pleased with the fruits of my labor.

One night as I lay in bed, I noticed that my visitor was shivering more than usual. I almost spoke, thinking to offer an extra blanket, but bit the words back. And in that moment I lit on what my next project on the loom would be.

I would make a soft flannel nightshirt for my visitor, for the furless white bear, as I had come to think of him. And I would use his own fur to make the flannel even warmer. Whenever I had come across a tuft of white fur in the castle, fur the white bear had shed, I would collect it. It had been sheer instinct, a throwback to the lean days when I had saved every bit of sheep's wool I found on bushes, fences, and the like. And the bear fur was so luxuriant, so soft, I hadn't been able to curb my thriftiness and so had accumulated a large basketful.

I had never spun bear fur into thread, but with the marvelous spinning wheels in the castle, I thought I'd be able to manage it. I mingled the bear's fur with some soft (and very white) sheep's wool I had found in a bin, and soon I had spun enough yarn for my purpose. I cast the silky thread onto the loom and began to weave.

The white bear was absent during much of this time. It was nearly spring, according to my crude fabric-calendar, though I could not tell if the tree branch I saw through my window had any buds on it.

It was while working on the nightshirt that I set myself the project of learning more of the Fransk language. Mother had claimed I had a talent for learning languages but had wasted it because I would not sit still long enough to be taught. The only reason I let her teach me Fransk at all was because I was certain I would be traveling the entire world on the back of my imaginary white bear and would need to know as many languages as possible. Fransk was the only language my mother knew with any fluency, but she also had taught me what she knew of the Tysk and Grönländer dialects. And I was always eager to pick up any foreign words from strangers who passed through our part of the world.

I was close to finishing the nightshirt when I was hit by a terrible feeling of homesickness. It was the first time since those early weeks of living in the castle that I had felt it so strongly. It may have been the thought of spring, or maybe just that I had been in the castle for so long, but whatever the reason, the feeling was overwhelming. I tried to ignore it and concentrated on the soft white cloth.

I was fashioning it into a long, generously sized shirt. I decided against buttons or ties, thinking that if I was correct, paws would not do well with them. I made it so it could be pulled on over the head. If I was wrong, and my night visitor was not a bear but a person, then a small brooch could be used for fastening at the neck. In fact, I found such a brooch in the music room. It was fashioned in the shape of a silver flauto, very similar to the one that held the position of honor in the box with the blue-velvet cloth.

On the night I finished the shirt, I laid it carefully on the far side of the bed and placed the brooch beside it. I was intensely curious about what my visitor would do. Would it alter at all its nightly routine? Would it put on the shirt? Finally speak to me? Or would it not even notice the white shirt in the complete blackness of the room?

I lay waiting, tense with anticipation. Then there came the barely perceptible sighing sound of the door opening and shutting. No light ever spilled into the room, for at this time of night the hallway was pitchblack as well. There was the usual silence as my visitor crossed the room. Typically then I would feel the give in the mattress, followed by the adjustment of the covers. But this time the silence lasted longer. I strained my ears, all my senses. What was he doing?...Was he...? And then, yes, I felt sure the nightshirt was being lifted off the bed. A sound of rustling fabric, as though it was being slipped over a head, arms pushing through the sleeves. There came a very faint clicking sound, of metal against metal, as of a brooch being fastened.

Soon there was the familiar give in the mattress, the covers pulled up, and then, nothing. I had not expected words, a conventional thank-you, so was not disappointed in the silence.

In the morning the nightshirt was neatly folded at the foot of the bed, the visitor's side, with the brooch attached at the neck. This pleased me very much. It was a sign the shirt had been worn and appreciated. And I had noticed no shivering at all during the night.

While. I was dressing I kept looking at the folded bundle at the foot of the bed. Finally I could contain myself no longer and crossed to it, unfolding and pressing the nightshirt to my face. I breathed in.

I'm not sure what I was seeking, possibly the smell of the white bear. There was a trace of that smell, but it could easily have been because of the bear fur I'd used in weaving the shirt. But there was another very faint smell that I could not identify, nor put words to—a good smell.

Then I folded the shirt up again and placed it on the bed.

Each night I laid the shirt out on the side of the bed and every morning it would be folded at the foot. And my visitor never again showed any signs of shivering.

Every seven days I washed the shirt, along with my own clothing. It was one chore that from the beginning I had insisted on doing myself. In those first weeks I had set up a room especially for washing. It was one of the plainer rooms in the castle and had a generous hearth fire for heating water and the stones I used for ironing. The white woman and man caught on right away and made sure the fire was always lit on washing day. The nightshirt never got dirty or smelled any different from the first time I had put it to my nose, but I wanted to keep it fresh.

One washing day I had just given a final rinse to the nightshirt and was holding it up over the hot water. With steam rolling off its surface, I was thinking how the whiteness of the fabric had a ghostly sort of glow. Then I heard a sound. It was that sighing sound I had heard before, when I was trying on the moon dress and saw the bear through the doorway. And there he was again, standing in the doorway watching me, his eyes avid, almost hungry. Startled, I dropped the nightshirt back into the bucket and hot water splashed up on me, I let out a little cry and the white bear took a few steps toward me. Unhurt, I brushed at the water on my clothing, but my eyes locked with those of the white bear. He gave a low growl, like he was in pain, then he swung his head around and padded quickly away, down the hall.

The homesickness that had begun while I was finishing the nightshirt grew worse. It was intensified, I believe, because I had nothing more I wanted to make on the loom. Or it may have been my homesickness that made me lose interest in weaving, sewing, and spinning. Sitting there at the loom suddenly felt dull and tiresome.

I thought constantly of my family, trying to picture them as spring came to the farm. I did not know for sure that they were still there; in fact, they probably were not, in that they had been on the verge of moving away, but I stubbornly kept imagining them there, in all the familiar places.

I thought about the land around our farm, of my favorite rambles, of the snowdrops that would be coming up beside the creek, and the carpet of spring heather that would blanket the hills to the west. I would sit on the red couch by the hour, gazing vacantly into the hearth fire, thinking of the way the wind had felt on my skin. And the sun hot on my hair.

When I wasn't in the red-couch room, I would sit beside the small window at the top of the castle. I could then clearly see that the lone tree branch had sprouted the beginnings of leaves. I tried jamming my hand through the tiny opening in a ridiculous attempt to reach the leaves, but the branch was much too far away and all I got were scraped knuckles. Some days it was too painful to see the blue of the sky and the green of the new leaves, and I would retreat to the red couch.

The white bear would find me there and I could tell he was uneasy. His eyes watched me with a sad, unsettled look and his skin twitched, as if he was reflecting the restlessness and unhappiness he saw in my face.

I no longer spoke to him or told him stories. I was angry. After all, he was the reason I was not out walking my own familiar trails; it was he who had brought me to this prison. When those feelings grew strong, I would stalk out of the room and restlessly roam the corridors and rooms of the castle. The white bear did not follow me.

My unhappiness began to affect my sleep. I tossed and turned, uncaring whether or not I disturbed my unseen companion. Still, despite my unhappy state I did not violate the unspoken rules about trying to touch or speak to the visitor. Something kept me, just barely, from straying over that line. I still laid out the nightshirt but only out of habit.

I ate little and could tell that I was getting thin and unhealthy, yet I did not care. I had no will for anything except either sitting and staring or incessantly roaming the castle. I had lost interest in my makeshift calendar and no longer knew the day or even the month. Gradually my little spurts of anger at the white bear became the only moments I felt much of anything at all, and after a while even my anger grew dull.

One day I was sitting on the red couch, staring at nothing, when the white bear came into the room. He did not lie in his usual spot but stood facing me and spoke. I had not heard his voice in a long time.

"You ... are ill?"

"No," I said apathetically.

"No food ... pale."

"I'm not hungry."

"Then unhappy..." he intoned mournfully. "...lonely?"

I looked up at him. "I need to go home," I said simply, "or I think I might die."

I thought I heard a groan escape from deep in the bear's chest.

I felt a stirring of the old me. "You must let me go. For a visit only. Please."

He lowered his head in that nodding gesture I had come to know.

My heart started pounding. Home. Fresh air. The wind. I thought I might faint.

"When?" I asked, barely able to hide my excitement.

"Tomorrow." His voice filled the room, though faintly, like the knell of a far-off bell.

Neddy

IT WAS ONE OF THE fairest springs we'd ever had on the farm. Each day dawned clear and fresh, with a bright blue sky. And somehow the very beauty of the days sharpened my feelings of missing Rose.

Early in lambing season I began to notice that Mother and Widow Hautzig were up to something. They were always whispering together or spending hours in the woods collecting things they kept hidden. My guess was that they were concocting some sort of charm, either a finding charm to bring Rose back or a love charm to heal the rift between Mother and Father. If Father had been at home, I would have talked to him about it, but he was gone again.

Soren had told me about a scholar in Trondheim who was eager for an apprentice or assistant. After hearing about me, the scholar suggested that we meet. I knew Soren was longing for Father to move the mapmaking business to Trondheim, and that he was trying to enlist me in his efforts. Though I was sorely tempted to meet the scholar, I felt as Father did. Because of Rose I did not want to leave the farm. So I put Soren off, saying I was not ready yet, and thanked him for his generous efforts on my behalf.

One day I was walking from Father's workshop up to the house for the midday meal. Willem, Sonja, and I had completed the most recent order from Soren, and I was eagerly looking forward to spending the afternoon poring over the new books he had sent. I saw a figure dressed in gray standing in front of the farmhouse. She was facing away from me, but I knew at once who it was. "Rose!" I cried out, unbelieving.

She turned to face me. I ran to her, folding her in my arms, my eyes blinded by tears. Then I held her away from me, drinking in the sight of her standing there, solid and real. She looked thinner, but her face glowed with happiness.

"Rose, are you truly back? I can't believe it," I said. The smile on her face wavered. "'Tis only a visit, Neddy," she said in a quiet voice.

"Why?"

"I promised."

"The white bear?"

"Yes."

"Where is he?"

"He is gone but will return for me."

"How long?"

"One month."

"That is too short! Surely..." I stopped when I saw her expression.

Hearing our voices, Willem and Sonja came out of the farmhouse. There were cries of joy and many hugs, and shortly thereafter Mother and Sara came walking up the road, in company with Widow Hautzig.

"Rose? Is it Rose?" Sara cried, and soon Sara, Rose, and Mother were embracing one another all at once while Widow Hautzig looked on.

"Sara, you look well! You are fully recovered?" Rose asked.

Sara smiled and nodded.

"Oh, Sara, I am so happy to see you." And Rose embraced Sara all over again.

"But Rose, you are so thin!" Mother said, tears in her eyes, as she tightly clasped Rose to her. "Come inside," she said, pulling Rose into the farmhouse. "There is soup on the hearth. And then you must tell us everything!"

Rose was so busy gazing around the farmhouse that she seemed barely to hear Mother's words. "Everything is different," she said. "The new furniture. Fresh paint. What has happened while I was gone?"

"Ah, it is a long tale," Mother replied. "Sit down, and I'll fetch you a bowl of soup. Sara, get Rose a cup of apple mead."

Rose obediently sat. Then her eyes lit on the loom.

"Oh, it's Widow Hautzig's loom. How kind of you to give it to us," she said to the widow.

Widow Hautzig had the grace to look a little embarrassed, but Mother rescued her. "It is yours now, Rose. I knew you would be back." She and Widow Hautzig exchanged a look as Mother placed the bowl of soup in front of Rose.

"I ... I'm sorry, Mother, but I'm not really hungry. Where is Father?"

"Your father is not here, Rose," Mother replied. "He is a mapmaker now. Off on an exploring journey."

"And searching for you," I added.

"A mapmaker! Oh, I am so glad," Rose said happily. "When will he be back?"

"We don't know," I responded. "Last time he was gone nearly two months."

. "Oh no!" Rose said, obviously distressed. "I haven't much time..."

"What do you mean?" Mother asked sharply. "You are back to stay, aren't you, Rose?"

Rose shook her head. I could see her hands were tightly clenched in her lap.

"Rose is only visiting," I said. "She can stay for one month, no more. Come, Rose, let me show you Father's new workshop."

Rose quickly got to her feet, giving me a grateful look. "I'll eat later, Mother," she said as we went out the door.

"Is Father really a mapmaker, Neddy?" she asked. "Tell me everything!"

While we walked I told her the whole story, of all that had happened since she had left us. I didn't show her Father's workshop after all, not then, for we decided to keep walking until we got to our favorite spot, the hillside where Rose had first showed me the wind-rose cloak.

Rose listened in amazement. When I was done, I leaned over and took her hand. "Now it is your turn," I said. "Tell me where you have been and all that has happened to you."

She was silent. "I cannot, Neddy," she finally said.

She loosened her hand from mine and, standing up, threw her arms out and put her face toward the sun. "It is so good to be home!" she said, joy radiating from her.

I smiled. Then Rose leaned down and, grabbing up a fistful of heather, put it to her nose, breathing in deeply. I remembered how Rose always loved to smell things. I used to call her an elkhound; her favorite dog, Snurri, was an elkhound, and like all of that breed, he had a remarkable sense of smell.

"Oh, it's wonderful, Neddy. You don't know how wonderful." She went darting about, touching things, smelling them.

Finally she sank down beside me again. "I'm sorry, Neddy. I would like to tell you everything, but I cannot, not very much anyway. There were parts that were very, very nice. And there were some parts that were hard. Like not being able to do this..." She buried her nose in heather again. "And the loneliness. The being shut inside..." She shivered a little, then brightened. "But it is fine, Neddy. I don't mind going back, as long as I can have a little time like this."

"But why must you go back? You do not owe the white bear anything."

"Sara is well now," Rose replied. "And Father's workshop ... the good fortune that came to our family because I..."

"You sound like Mother! Rose, those things had nothing to do with the bear. It was coincidence, nothing more. Harald Soren, a flesh-and-blood man, brought about our good fortune, not the bear."

Rose looked at me. There was a yearning in her face, as if she wanted very much to believe what I said. "You can't know that, not for sure, Neddy," she said slowly. "And besides, I made a promise."

"To the bear."

She nodded, her eyes bright. I thought she might weep, but she didn't. "Don't let's talk about this anymore, Neddy."

"I won't press you," I said. "But if you do wish to talk about anything at all, I am here."

"Thank you," she replied softly. And we began making our way back to the farmhouse.

"What is that nasty Widow Hautzig doing here anyway?" Rose asked in a low voice as we saw Mother and the widow coming out of the front door.

"She and Mother have grown thick as thieves," I replied.

"What does Father think of it?"

"He barely notices, he's gone so much. And..." I paused. "Well, there is ill feeling between Mother and Father."

"Because of me?" Rose said quickly.

"It began then," I answered, somewhat unwillingly.

"I am sorry to hear it," Rose said. "Oh, how I wish Father would return!"

"So do I," I replied fervently. "What joy it would give him to see you back home."