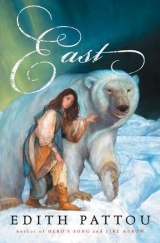

Текст книги "East "

Автор книги: Эдит Патту

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

Troll Queen

EVEN THOUGH I WAS little more than a child when I wrote in my Book about the green lands and about the softskin boy, I could see ahead to what I had to do.

I am very angry at Father. We are leaving tomorrow and he will not let me take the boy with me as my servant. He says we cannot take children. And especially not this boy, because of who he is—he is important to the people in the green lands, Father says, like I am in the Huldre land.

Father is king and must be obeyed. For now. But already my arts are close to being the equal of his, and soon I will have my way. I will come back to this place and find the boy, and then he will be mine.

White Bear

Here.

After so long waiting.

Her purple eyes.

Torn cloak.

Skin pale, sheer as ice.

Exhausted.

But unafraid.

Must remember.

Conditions, rules.

So long ago.

Playing.

A ball.

A voice like rocks.

Then...

Body split, stretched.

Pain. And...

All changed, in a moment.

Lost.

But now...

Hope.

Rose

WHEN I AWOKE, my head was heavy. But I knew where I was right away. At home, even in summer, there would be a cold tang to the air in the morning, and the mattress I slept on with my sister was not covered in velvet and overstuffed with down.

I sat up, stretching, and saw that the table had been cleared while I slept, except for a covered basket, a crock of butter beside it, and a large white teapot. Steam was rising from the pot's spout. My stomach growled and I realized I was ravenous again.

I stood and made my way to the table. I lifted the white cloth and breathed in the aroma of cinnamon and hot dough. Breaking off a piece of bread, I slathered it with butter and shoved it into my mouth. We hadn't been able to afford butter in a very long time, and I closed my eyes in sheer delight. I then drank a cup of what turned out to be a sweet, fragrant tea, exotic and fruity, like none I'd had before.

As I stuffed myself with bread and butter, I wondered where the food had come from. Was there a kitchen with a bustling staff of servants? Or was the food the result of an enchantment?

My stomach full, I got up from the table and set off to explore.

I thought of the white bear and felt uneasy, fearing that he might spring out at me from inside a room or around a corner. But there was no sign of him.

I started down a hall with a vaulted ceiling. The walls were a light polished stone, and sconces holding oil lamps were placed at regular intervals. In between the lamps were large paintings and tapestries. The tapestries in particular drew my eyes; they were done in vivid hues of reds and blues, and depicted lords and ladies in old-fashioned courtly garb. The handiwork was exquisite.

I came to an open doorway and peered in. It was a drawing room, and it, too, was filled with paintings and tapestries. There was a lush deep-green carpet and various pieces of overstuffed furniture. As in the hallway, light was provided by oil lamps, both on the walls and set on tables. I picked up one of the handheld lamps and took it with me in case there were places not so well lit.

I continued my exploration. The next room I came to was also furnished with tapestries, rugs, and overstuffed furniture, as well as shelves of books lining the walls. The library, I thought. But I was wrong. Many of the rooms turned out to have books. Finally I came to one that could not be mistaken for anything but a library. No tapestries there—every inch of the walls was covered with shelving, from floor to ceiling. It took my breath away. In Njord the only places I knew to have so many books were the monasteries. If only Neddy could see this, I thought, but I quickly brushed the thought away. I wouldn't think about Neddy now.

In addition to the many books I found in the rooms I explored, I also noticed something else that was plentiful. Whoever had decorated this place clearly had a love of music. There was a musical instrument in almost every room.

Then I came to a large room that was devoted entirely to music, as the library was devoted to books. It was breathtaking. In the center of the room stood an enormous grand piano, beautifully painted and carved. And in a large ornate cabinet was an astonishing collection of pipes and flautos that appeared to have come from all over the world. There was a lacquered bamboo flauto in the shape of a dragon that looked to be from the Far East, and there were pipes made of ivory, reed, and soapstone. Some were elaborately carved, some had double pipes, but there was one flauto that was clearly favored. Displayed in a beautiful box lined with blue velvet, it wasn't fancy like some of the others but had a simple, classic beauty.

There were sheaves of sheet music tied up with ribbon, and there were chairs lining the sides of the room that looked as if they could be pulled out to form rows for an audience. If I closed my eyes, I could imagine a gathering of finely dressed ladies and gentlemen seated there on a Sunday afternoon, applauding enthusiastically for the performance of a musician. I liked the room very much, although there hung an air of sadness about it, perhaps because it was empty of people.

I went into room after room. I was going to count them but quickly gave up. The place was enormous, and because of its size I began to think of it as a castle.

I got the feeling that the castle was carved right into the mountain, which was impossible, yet by then I had become accustomed to impossible things. There were no windows or doors that I could see, save for the large door we had entered. Most of the rooms looked as though they had not been used in a long time. It was not because they were stuffy or dusty (in fact, they were neat as a pin), but there was a general sense of emptiness, even loneliness, about each room.

I became more and more intrigued as I explored, forgetting completely my uneasiness about the white bear.

I began to weave a picture in my mind of whoever it was who lived there (other than a white bear). It became a sort of game to piece together the clues that revealed him—Well, that was the first thing I figured out—that it was a man who lived there. There was little of a feminine touch in most of the rooms I had seen.

He loved music. And books. I thought again of the library. Neddy.

I was suddenly hit with a pang of homesickness so severe that I sank down on the thick blue carpet of the room in which I stood. I had been so swept up in the wild ride getting there and then exploring the castle that I had barely thought of my family at all. There I was, thousands of miles from those I loved most in the world, in a strange deserted castle, no doubt with an enormous white bear prowling somewhere nearby.

A chill went through me and I wrapped my pieced-together cloak tighter around my shoulders. Oh, Neddy...

I am not one who cries easily, but at that moment tears spilled from my eyes. I don't know how long I sat there, huddled into my cloak, feeling miserable.

It was hunger that finally got me to my feet and moving again. It had likely been hours since the hot bread and tea. But I wasn't sure how to find my way back to the room where I had eaten. So I decided to go forward, and rushed down the corridor, ignoring the rooms to either side of me, thinking I might find a stairway that would take me back down to the floor where I had begun.

I had just glimpsed a flight of stairs and was heading toward it when something caught my eye—a door was slightly ajar and I could see lamps lit inside the room. The merest hint of color and light flashed out at me. I pushed the door open and then caught my breath in amazement.

A loom. It was the most beautiful loom I had ever seen, more beautiful than I could ever have imagined. It was made of a rich chestnut-colored wood that was polished so that it gleamed, and the posts were carved with intricate designs, as were the crossbeams. The warp threads had been set up with an astonishing palette of wool in such rich colors as the pale green of early spring grass and the purple of fleur-de-lis.

I ran my fingers reverently along the threads. In a sort of trance I sank down on the small stool that was perched in front of the loom, as if it had been waiting for me. I felt like I was in a dream, watching myself, but I took up the shuttle and beater and began to weave. Though it was a completely unfamiliar loom, with a different feel to the shuttle and the tension in the warp threads, it took only a few passes before I understood it, and then I was gone, lost in the world of texture, color, and movement that I loved so well. I could feel the grass brushing against my bare feet, and the violet smell of the fleur-de-lis was thick in my nostrils.

The loom was like a Thoroughbred compared to the worn, stumbling workhorse of a loom I had used in Widow Hautzig's shed. And working on it was as different as the looms themselves. It was the difference between walking with a stranger and walking with your heartmate. It was the difference between working for duty and working for love.

I have no idea how long I wove.

With no window to the outside world, I could not keep time. I might have been an entire day at the loom, or even longer. What finally brought me to my senses was hunger. My head was light and there was a faint buzzing in my ears. But still I could not stop. My fingers slowly moving, I gazed around the room.

There wasn't just the one loom but several others—small hand looms, a weighted loom similar to the one at home, and an upright loom that I guessed to be a tapestry loom, though I had never seen one before, only heard Widow Hautzig describe them. In addition to the looms, there were several spinning wheels (which I would have gone to examine more closely if my knees had not been so weak) as well as shelves filled to overflowing with everything that one could possibly want for creating cloth and sewing it together.

There was a whole section of shelving devoted entirely to thread. A rainbow of colors and textures. Some spools even looked to have silk thread on them, with colors that included shimmery golds, silvers, and bronzes.

There were bins of carded wool, baskets of raw fluffy wool awaiting carding, and skeins of finished wool, ready for weaving. There were bottles of liquid color for dyeing and bowls of powdered pigment in every color ever seen in nature and some I had never seen before. There were sharp, glittery scissors, needles for knitting, and sewing needles of every thickness and length. I was dumbstruck.

But finally, I knew I must find something to eat or I would become ill. I lurched to the door and out into the hall. My head swimming, I made my way to the stairs. Just looking along the curving staircase made my ears ring and my legs shake, but I started down anyway. I finished my descent sitting, dragging my rear down each step like a very young child.

At the bottom I pulled myself upright using the banister and began to walk forward. I sniffed the air for the smell of stew, but there was no scent. I began to worry that I was far from that room where I had eaten. Or that the food was in a different room.

Or worse, that there would be no food at all.

At the end of the hall I rounded the corner, and standing there was the white bear. He was somehow larger and whiter than I remembered. I let out a small scream and fell clumsily to the ground. I felt close to fainting but took several deep, gasping breaths and the feeling passed.

The white bear watched me with his sad black eyes. Then he said in that hollow deep voice that always seemed like it was wrenched from him, "There is food. Come."

I got up shakily and followed.

After a while he stopped, and I stopped, too, stumbling a little.

"If you need ... grab ... my fur."

"Thank you," I replied, my voice thin. I was too addled by hunger to be afraid. I reached up and set my hand on his back.

He started walking again, and I followed along to the room he had led me to before, when we had first arrived. I did stumble once along the way, and kept myself from falling by grabbing a handful of white for. He didn't pause or flinch.

Once again there was a stewpot on the hearth, with a thick soup of lentils and ham bubbling inside. The white bear stood in the doorway, watching me for a moment, then he turned and disappeared.

As I ate, my mind whirled with thoughts about this extraordinary place and all the things in it—the loom, the delicious food that appeared out of nowhere, and most of all, the white bear.

Troll Queen

BEFORE I TOOK THE softskin boy, I went back several times to the green lands. I traveled in my own sleigh, taking only Urda, and I did not try to talk to the boy but only watched, learning of his life. I wrote in my Book:

It seems these softskins die with great frequency; their lives are shortened by a wide variety of illnesses and accidents. The boy I watch is a fifth-born child, but two older than he have already died. It shall be no surprise then if he, too, shall seem to perish.

It was simple, the plan I came up with. I chose an ill-favored troll to sacrifice, one who would be little missed in Huldre, and then with my arts summoned up a very simple act of shape-changing.

If only my father had not been so angry.

Neddy

IT IS ODD, THE TWISTS that life will sometimes take. The ewe that you think will give birth with ease dies bringing forth a two-headed lamb. Or the ski trail that you have been told is treacherous, you navigate easily.

The days that followed Rose's departure were dark and more painful than anything I could have imagined. Father was a ghost of a man, pale and hollow-eyed, moving about the farm clumsily, as if he didn't belong there. He avoided all of us, especially Mother. She spent her time with Sara. It was as if she believed that by nursing Sara and restoring her health, she could justify Rose's sacrifice. But of course nothing could. Not ever, not even if Sara were to suddenly leap from her bed, fully recovered. As it was, there was no change in her condition.

I spent my time in a dazed sort of twilight world, going about my chores, but my mind was always on Rose, imagining her in every possible situation except the one that ended with her gone forever.

Outwardly we busied ourselves with getting ready to leave the farm. Neighbor Torsk was kind and helpful; I think even in his simple way he was aware that something was very wrong with our family. Mother told him that Rose had gone to live with relatives in the southeast for a time, and that the rest of us were hoping to follow her as soon as Sara's health improved.

At first, because Father was so lost in grief, my brother Willem and I did all the heavy work about the farm—repairing and cleaning and sorting. But after several days Father set aside his lost look and threw himself into the labor with a frightening intensity, as though work was the only thing that kept him from madness. By the end of the week our farmhouse looked as good as it possibly could have, given our reduced circumstances.

The day before the landholder was due to take possession of his property, we had nearly finished with the packing; there was so little worth taking away with us. I was out by the henhouse, feeding the few scrawny chickens we had left, when I heard the sound of wagon wheels. Soon a handsome wagon pulled by two gleaming horses came into view. I called out to Father, who was nearby. Mother was at neighbor Torsk's with Sara.

The wagon came to a stop and a tall, well-dressed gentleman alighted and stood for a moment gazing at the farm. He had a look of ownership about him, and I knew at once that the landholder had come a day early. My heart sank a little. Though I had been expecting that moment for a long time, it still pained me. Then the man strode toward Father and me, a pleasant expression on his face. "You must be Arne," he said to Father, extending his hand.

"Master Mogens?" my father said hesitantly, taking the proffered hand.

"No, Mogens works for me, watching over my holdings. I am Harald Soren, the owner of this property."

"Well met, Master Soren. This is my son Neddy."

I shook the man's hand, impressed in spite of myself at the kindness and intelligence I saw in his eyes. I had spent much of the past months disliking—even despising—the man, but now that he was in front of me and the day had arrived for him to take away the only home I had ever known, I could not help but think he looked a good and decent fellow.

"I hope you will find everything in order," my father said stiffly.

"Oh, I am sure..." Master Soren began. "But first, let me apologize for arriving a day early. The journey took less time than I had thought it would. The map I used was poor," he said with a frown. "It is difficult to find maps of decent quality." His eyes held an exasperated look, then he gave a shrug. "At any rate, I have taken lodgings in Andalsnes. And I can come back tomorrow if that suits you better."

"Oh no, today is just as good as tomorrow," Father replied with courtesy. "May I show you around the farm?"

"That would be most kind of you."

I wondered what must have been going through Father's mind as we took Master Soren through the farmhouse. For myself, I found it hard to hate the man, with his shiny boots and kind eyes, looking over my home as if he were assessing a mare he had just acquired.

Then we came to the storage room. Father still had not taken down the few maps he had hung, maps of his own design, made back when he was apprentice to my grandfather. I also saw that all of our wind rose designs lay scattered over the worktable, with Rose's on top.

I heard Master Soren give a sudden intake of breath. He quickly strode over to the nearest map pinned to the wall and studied it closely, his concentration focused and intent.

I saw him trace Father's signature with his finger, then he turned, his eyes bright, and said, "Am I to understand that you made this map?"

"Yes, though it is many years old..."

"Did you, by chance, apprentice with Esbjorn Lavrans?"

"Yes," Father answered, and smiled for the first time in many days. "Esbjorn was my wife's father. He died some years ago."

"Well I know. A great loss, it was." Soren paused. "I had heard there was an apprentice, but no one knew anything about him, after Esbjorn's death. And since then I have had to get my maps from Danemark, at great cost and much difficulty. Even then, they are either out of date or incomplete. And the maps of Njord..." He gave a snort to indicate his contempt.

Then his eyes fell on the wind roses. Again he moved forward, his eyes alight.

"May I?" he asked. Father dumbly nodded, and we both watched as the man slowly and reverently looked at each design.

"But these are superb!" he exclaimed, lowering the last into the box. "How is it that I have never seen or heard of your work before?"

"Because I have done none," Father replied. "Except for my own pleasure, when time allowed. I am a farmer now."

Harald Soren gazed at Father and a silence grew in the small room. When Soren spoke at last he sounded angry. "It is a waste then, a shameful waste."

Father's mouth opened, and I thought he looked angry as well, but he said nothing.

Then Soren smiled and spoke, his voice warm. "Such a talent as you possess! It is a damnable waste for one such as you to be spending your time mucking about with pigs and plow horses. Not that farming isn't a noble calling ... But mapmaking! Come, let us find a place to sit. I would talk with you further about your maps. And I could do with a cup of grog or whatever you have on hand."

Father looked stunned. "Of course," he said. "I should have offered sooner..."

"I'll go," I said to Father.

"Thank you, lad," said Soren. "Now, Arne, show me all your maps and charts and wind roses. I must see everything."

And so it happened that while I served them cups of watery ale and some stale bread and cheese, the two men put their heads together over Father's precious pile of maps. And they were like two children with a game of hneftafl. I had not seen Father so happy in a very long time.

Soren was a good man. It had been his assistant, Mogens, who'd made the decision to evict us. Soren was an ardent voyager and left most of his affairs in Mogens's hands. But being between journeys, he had a mind to come himself to see the farm, which had been so long in the hands of one family, with the thought that he would like to know more of that family's circumstances before he turned them off the lands.

"Mogens means well," Soren explained, "but he can be a bit rigid in following the dictates of business."

Soren asked Father many questions, and by the time twilight came he knew more about our family than most of our neighbors. When he learned of my sister Sara's illness, he expressed the sincerest of concern and sympathy. The only thing Father did not tell Soren about was Rose and the white bear. Instead he told the same lie that Mother had told our neighbors—that his youngest daughter, Rose, whose wind rose design Soren had particularly admired, was visiting relatives in the south. Father's face was so stiff and white when he said the words that I was sure Soren sensed something amiss; but if he did, he chose not to question further.

When Soren left that evening for his lodgings in Andalsnes, he said, "I will return tomorrow to talk with you further, Arne. But there will be no more mention of leaving your farm."

Father and I stood watching as Soren's carriage rattled down the road and out of sight. We then turned and stared at each other with the stupefied expressions of men just awoken from a dream.

Soren did not return the next morning.

I began to think that the whole encounter was a dream, or some sort of cruel trick. But later in the afternoon Soren came riding up in his wagon, bringing with him the doctor from Andalsnes. It was I who brought the doctor to Sara at Torsk's farm, while Father stayed behind to talk with Soren.

Dr. Trinde bade us leave the room while he examined Sara. As we waited I told Mother, Willem, and Sonja all that had happened with Soren.

When I had finished, Mother said to me, "Is this true, Neddy? We don't have to leave the farm?"

I nodded. Mother closed her eyes. Clasping her hands together tightly, she was silent, her face pale. Then her eyes opened, and leaning close, she stared at me, a strange smile on her face.

"This happened because of the white bear," she said in a low voice, her eyes fixed on mine. I looked back at her in astonishment, which quickly turned to anger. That she should use the fortunate turn of events to justify Rose's sacrifice ... I shuddered with revulsion and pulled away from her.

"Mother..." I began, my voice raw, when suddenly the doctor appeared.

"I have here a list of herbs that I will need for Sara's treatment," he said, unaware of the tension in the room. I tried to focus on his words. "You should know," Dr. Trinde went on gravely, "that it will be touch-and-go for a few days, but," and he paused for a moment, "I think there is every reason to believe that Sara will pull through."

Mother's eyes filled with tears, and she reached out and hugged me tightly to her.

"You see?" she whispered. "It was all for the best."

I pulled away sharply. Then, grabbing the doctor's list of herbs, I slammed out of Torsk's farmhouse.