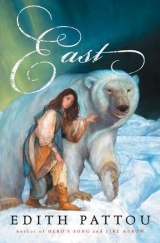

Текст книги "East "

Автор книги: Эдит Патту

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

Rose

IT WAS AFTER MIDNIGHT when he spoke again. We were moving through a gorge and I had been half asleep. "What did you say?" I mumbled groggily.

"Did they ... your family ... ask you ... do anything?"

I thought a moment, then said honestly, "They asked me to stay with them."

"Nothing else?"

"No."

"You ... are sure?"

"Yes, I am sure." I wondered what lay behind the question, what it was he feared.

"Your mother ... did she not ... ask you ... give advice?"

"I told my mother only a little. Enough to reassure her that I am safe. I am safe, aren't I?" I asked boldly.

The white bear made a sound that could have been a chuckle. "You are ... safe," he replied after a few moments.

I didn't know how I was going to feel when the doors of the castle shut behind me, but as with leaving my family, it wasn't as hard as I had feared. The memory of moonlight and cool night air was still fresh, and perhaps it would last me a long time.

I climbed off his back and stood before him in the front entryway of the castle. There was an awkward moment, as though neither of us knew what to say or what to do next.

Then the white bear said, "Thank you ... for coming back," and turned to walk away.

"Wait," I said. "Can you not...?" I groped for the words. "Please ... tell me why I am here, and what it is I can do to ... help you?"

He turned and looked at me. "...Cannot."

Then I couldn't help myself. I was already feeling the walls close in on me. "Am I to be allowed to visit my family again?" I blurted out.

I thought his head drooped a little at that, but he lifted it and said, "...not talk of that ... now." He disappeared down the hall, his massive feet making no noise on the thick carpet.

Well, at least he hadn't said no, I told myself, and made my way to the room with the red couch.

***

I was happy to see the loom again and had many ideas for clothing I wanted to make for my family. But I set diem aside for the moment. I was much more focused on a new thought: During the journey back to the castle, I had vowed to get to the bottom of the mystery surrounding the white bear.

The obvious source to learn more about him was the two servants.

I began to spy on them, being careful so they wouldn't guess what I was up to. I would go to my loom dutifully as they expected me to, then would sneak out into the halls of the castle to see where the two of them were. As time went on I observed a pattern to their daily schedule and began work on a map of their movements. First I came up with a list of their duties, the jobs they did to keep the castle running—at least those things that were visible to me: starting and tending the various hearth fires; lighting, filling, and putting out the oil lamps; providing me, and themselves, with meals (I suspected the white bear did his own hunting outside the castle); general cleaning, dusting, and so forth. I had no idea where they got the raw materials for making meals, but having seen no sign of chickens or cows or vegetables growing in the castle, I determined they must have such things delivered. If that was the case, the deliveries had to be made infrequently and at odd hours, because I had never seen any sign of the front door opening.

Unless it was all done by magic. Yet even though I was living with a talking white bear in a castle inside a mountain, my mind still rebelled at the whole idea of magic. After all, I hadn't seen any mystifying transformations, things flying through the air or anything like that. The unlightable darkness of my bedroom and the lamp that went out for no reason were the only real signs that anything supernatural was going on.

I made it a point to wander along the hallway with the tapestry-covered kitchen door, and whenever I saw the two servants, I tried to be friendly. I would smile and speak a few words, offering by pantomime to help them carry things.

The woman would smile back blandly but remained aloof, resisting my efforts. I could see, however, that the little man was interested. He would nod and smile back, and once he let me carry wood for him. The woman was with him then and she frowned, saying something in their language that prompted him to take the wood back from me.

Clearly, if I was to have any luck at all communicating with the man, I needed to catch him alone.

According to my map the woman servant laid the fires in the rooms I used most—the one with the red couch, my bedchamber, the laundry room, and the weaving room. While she was attending to those, she sent the little man to check whether I'd used any of the other fireplaces during the previous day. If I had, which was rare, he was in charge of laying them afresh, after reporting to her.

So one afternoon I used a candle to light a fire in a small room on the second floor, as far away as possible from the kitchen or any of the other rooms the woman would be working in. It was a library of sorts, though it had fewer books than the big library on the first floor.

The next morning I got up early and hid myself in the second-floor room. I watched as the little man entered and inspected the fireplace, which had ash and burnt kindling in it. He lit the lamps in the room and then left, so I settled myself with a book in a large, comfortable chair. A little while later the man opened the door. Seeing me sitting there, he began to back out of the room, but I hopped up and, smiling warmly, beckoned him in. With a quick backward glance out into the hall, he slowly entered, carrying his bundle of wood and kindling.

"Hello," I said brightly.

He just stared at me.

Then I said, "Rose," and pointed to myself.

Again he looked at me dumbly.

I did it again. "Rose."

Something lit in his eyes. "Tuki," he said, and pointed to himself. I couldn't be sure if Tuki was his name, or nationality, or even species, but I nodded enthusiastically and pointed to him, saying, "Tuki."

And to my pleasure he responded by pointing to me and saying, "Rose."

I clapped my hands with delight. And then I pointed to the book I was holding and said, "Book."

He looked a little puzzled but then pointed to the book and said, "Kirja" which I hoped meant "book" in his language.

After that he set down the wood he was carrying, and we went around thè room pointing to things, each giving our own name for it. He seemed to enjoy this greatly, as if it were a splendid game, and I wondered if, despite the fact that his features looked adult to me, he might not actually be a child.

As we moved around the room, he would deliberately brush against my arm or hand, and I remembered the first time we had met and how he had appeared to be fascinated by my skin. And for myself, I was struck again by the white-ridged roughness of his.

When we came near the fireplace, he suddenly remembered his reason for coming to the room and quickly retrieved the wood. While he hurriedly laid the fire, I sat in a chair and watched him. He finished, then gazed at me, a questioning look on his face.

I nodded, and only a moment after he had bent over the wood, flames sprung up. I hadn't seen a striker or a candle and wondered if he had used some kind of magic spell to light the fire.

I pointed at the flames licking the logs and said, "Fire."

He looked at me, grinned, and said, "Palo." Then he left the room.

"Good-bye, Tuki!" I called to him.

I was pleased. This was a good beginning.

One of my favorite rooms in the castle was the music chamber, even though I didn't know how to play any of the instruments. Occasionally I would sit at the pianoforte and play on the ivory keys, but I could not make a melody out of the sounds.

The instruments that I liked the most were the flautos and recorders, especially the lovely flauto in the box with blue velvet. It was so beautiful I had been shy about even touching it, but one day I worked up my courage and took it out of the cabinet. I placed the mouthpiece to my lips and blew. A loud ringing note came out, startling me so that I almost dropped the instrument. But I held on and tried again. As that second note died away, the white bear entered the room. I fought down the instinct to hide the flauto behind my back as though I were a naughty child caught playing with grown-up things. As he came closer I could read a sort of yearning in his eyes. He lay down on the rug near the cabinet and looked up expectantly, as he did in the weaving room when he was ready to hear a story.

I shook my head. "I don't know how to play," I explained, my cheeks a little red.

"Play," he said.

"I can't." But he just stared at me with those yearning eyes. So I tried.

And though the tone of the instrument was lovely, my playing sounded like two birds of different pitch scolding each other.

The white bear closed his eyes and flattened his ears against the sound.

"Well, I warned you," I said.

Then he got up and crossed to a polished wooden chest and, using a large paw, pushed the top up. I could see bundles of paper inside, some bound, some tied with ribbon. I knew what the papers were.

"I cannot read music," I said.

The white bear sighed. Then he turned and left the room.

After he'd gone I went to the chest and sat down beside it, taking out a bundle of the papers with music written on them.

It became my new project, learning to read music. I was lucky to find a book in the chest that showed which note corresponded to which hole on the flauto.

Occasionally the white bear would come into the music room and sit and listen while I practiced, which made me self-conscious. But he never stayed long. It was as if he could only take it so long, hearing the music he knew mangled beyond all recognizable shape.

Meanwhile, the nighttime routine had taken up where it had left off. My first night back I saw that the white nightshirt was neatly folded at the foot of the bed. I picked it up, shook it out, and then carefully laid it on the side of the bed.

When the lights went out (and I still stubbornly kept at least one lamp or candle lit each night, just in case the enchantment might fail), I felt my visitor climb into bed and pull up the covers. I thought I heard a sigh, the kind of sigh a child would give after a thunderstorm is over, a sound that said that everything was once again all right. My throat grew tight with sympathy, and I felt pangs of guilt thinking of how cold and lonely the bed must have felt in my absence. I wondered if he had worn the nightshirt.

I began to have dreams about my nightly visitor. The first was actually a pleasant dream in which I awoke in the morning to find the white bear by the side of the bed, wearing the nightshirt (which had magically expanded to fit his large frame), and he was telling me he would take me home. So I climbed onto his back and we floated up into the air and flew above the land until I could spy my family's farmhouse below. We began to descend, too fast I thought, but the white bear said, "You are safe," and we landed softly in a field of snowdrops.

When I actually awoke in the morning after that dream, I half expected to see the white bear standing by the bed, but in the dim light from the lamps in the hall, I saw only the empty space beside me.

Sometime later I had another dream that was very different. In the dream I had managed to light one of the oil lamps. When I brought the lamp close to the stranger, I saw that its face was green and scaly and had a long, thin tongue that slithered in and out of its mouth while it breathed. I let out a cry and the monster awoke, opening a pair of hideous yellow eyes. Its tongue then brushed across my face and I woke up screaming, this time for real.

Again it was morning and I could see in the dim light that my visitor was gone, but I shuddered. What if it was a monster that lay beside me every night?

Tuki must not have said anything to the woman about our first encounter, for the next morning he appeared in the room where I sat waiting for him.

We went through much the same routine as before, teaching each other new words. I wasn't at all sure we would ever get to a point where we could actually converse and I could ask him questions about the white bear, but I felt I must try. And I believed the most important thing about my getting to know Tuki was the feeling I was finally doing something.

This went on for several weeks, though I was constantly worried that one day the woman would figure out what was going on and put a stop to it. Tuki seemed to trust me, even like me, and I was growing fond of him. He was so like a child—eager to please, sometimes impatient, and always wishing to be praised and petted.

We ran out of things to point to, and not wanting to upset our routine by shifting to another room, I began to use books, pointing to illustrations in them to continue our makeshift language lessons. Tuki was not a quick learner, but his eagerness to please kept him trying, and he was starting to remember some of the words I was teaching him, like Rose and hello and good-bye.

I found his language difficult but was beginning to understand parts of it. I made a little dictionary, to which I added new words every evening before bed. I kept it hidden in the closet, in my pack from home.

Finally I decided the time was right to introduce the subject of the white bear, and in preparation I went through practically every book in both libraries until I came across a book on animals that had a small picture of a white bear. I took it with me to the room on the second floor.

When we began our game that morning, I casually picked up the book about animals and began to leaf through it. I pointed to pictures of a wolf ("susi"), a beaver ("majava"), a rabbit ("kaniini"), and then finally came to the page with the white bear on it.

"White bear," I said.

"Lumi karhu" he said, then added, "vaeltaa." Then he looked at me a little uneasily. I cast about in my mind for words he might recognize that would help me ask him about the white bear. But I realized that nearly all the words I had learned were objects, not verbs. Annoyed with myself for not being better prepared, I decided I would have to settle for knowing the name for white bear in Tuki's language. It was a start.

"Lumi karhu?" repeated. "Or is it 'vaeltaa'?" He nodded at both, and I got the impression that they were two separate names for white bear. I wished I could press him, but I could tell he was uneasy. To distract him I pointed to more animals and we resumed our game.

The next time I brought a book of maps I'd found in the library. It was a beautiful volume entitled Ptolemy's Geographica, and in addition to the maps, which had been wrought in vivid colors and gold leaf, there were detailed drawings depicting the various regions of the world. I had heard of Ptolemy from my father; he was a Greek who had lived centuries before and was one of the first mapmakers. I thought of Father with a pang. How he would have treasured such a book.

I opened to a map of Njord and pointed to the spot where the village of Andalsnes would be found. "Rose from here," I said.

He stared down at it, shaking his head, mystified.

"Tuki from where?" I asked, riffling through the pages of the atlas, a questioning look on my face.

He smiled to see the pages fluttering and reached over to take the book, wanting to do it himself. Gleefully he thumbed the pages, causing them to cascade down. He did it over and over—fast, then slow. Suddenly something caught his eye, and he stopped and paged back to what he had seen.

With a smile he pointed to a small drawing that lay next to the map of the far northern land of ever winter that lay within the Arktik Circle. In this book the land was called Glacialis. In my country we called it Arktisk. The illustration Tuki was pointing to depicted high ice cliffs amid a frozen landscape of snow.

"Tuki is from Arktisk?" I asked.

He shook his head, not understanding.

"Tuki from a land of snow?" I hugged myself, as if cold.

He nodded enthusiastically, hugging himself and pretending to shiver. "Tuki," he said, pointing again to the picture of ice cliffs.

Then I pointed to the wind rose at the corner of the page. "North?" I asked, pointing to the N at the top.

He shook his head, again not understanding. I sighed.

That day I learned the words for snow ("lumi" which explained the first word Tuki had used for white bear) and ice ("jaassa"), and then he came out with the word "Huldre." I wasn't sure, but I thought maybe it was the name of the land he was from. And I got the impression that Tuki was homesick for his icy home; his face had taken on a sad, faraway look.

Several days later we were looking through some other books I had brought from the library. We came to a picture of quite a grand palace in a book of old tales.

"Jaassa" he said excitedly, jabbing his finger at the drawing. I was puzzled, wondering if the same word was used for ice and palace in his language.

"Ice?" I said.

"Ice," he repeated, nodding and pantomiming cold.

Was he trying to tell me he lived in a palace in his icy land? I was becoming frustrated. If only I could ask him straight out what I wanted to know: Where are you from? Who do you serve? Who sleeps in the bed with me at night?

Suddenly I got an idea. I took up a book and skipped to the end, where I found several blank pages. Heedlessly I tore them out, and while Tuki looked on with interest, I found a burnt stick in the fireplace. Using the charred end, I drew three stick figures, two female and a male. I pointed to one and said, "Rose," then to the male figure, saying, "Tuki." Finally I pointed to the third figure, on which I had drawn an apron, and turned to Tuki with a questioning look.

"Urda," he said after a moment, a delighted look on his face because he understood the new game I was playing.

"'Urda,'" I repeated with a smile. Then I turned the paper over and drew, as best I could, a bed. On one side of the bed I drew the stick figure that represented me. I pointed to it, saying, "Rose." I pantomimed sleeping. Then I pointed to the empty space beside me on the bed.

"Tuki?" I asked, though I knew he could not be my visitor, who was at least my size, probably larger.

He shook his head, mystified.

Then I said, "Urda?" My heart was beating fast. I felt I was on the verge of learning something important.

Again he shook his head.

My finger shaking slightly, I once more pointed at the empty space beside me. "Lumi karhu?" I said. "White bear?"

He looked wary, the way he had the first time I had brought up the white bear.

"White bear sleep with me?" I said, my voice cracking a little.

Suddenly the door swung open and there stood the woman called Urda. She looked at us. Then she quickly crossed the room and took Tuki by the wrist. She pulled him from the room, speaking sharply as she did. She did not give me so much as a backward glance.

Troll Queen

SHE IS CLEVER, more so than I gave her credit for. But her efforts to know the truth are fruitless. And I am pleased rather than disturbed by her actions, for they mean that, very soon, her curiosity will overmaster all else and then it shall be over.

He will be mine. Forever.

But she has raised his hopes. Too high. And I cannot help feeling sad for the disappointment he will soon know. (How strange to have such a feeling! If he were still alive, Father would say that is what comes of consorting with softskins.)

But the disappointment will fade; indeed, it will be only a short time before he has no memory at all of the softskin girl he set his heart on.

Neddy

FATHER RETURNED home a week after Rose left.

"How is it that you, all of you, allowed her to return to the white bear?" he asked in disbelief.

"She said she must," I told him. "We could not change her mind. You know Rose when she is set on a thing."

"Was she bewitched, do you think?"

I shook my head. "She seemed herself, Father."

"She was well?"

"Yes. A little thin when she first arrived. But Mother fattened her with all manner of good soups and meat pies."

"Then she is not well fed at this—what did you call it?..."

"Castle in the mountain," I replied. "She said her meals are more than ample. It was homesickness that caused her to lose her appetite."

"Then will she not be homesick again? Oh, would that I had been here!"

We were having this conversation in Father's workshop, just the two of us. Suddenly the door flew open and there stood Mother, pale and breathing hard.

"I have done something ... Oh, Arne..." And she sank to her knees, weeping.

I stared at her in confusion while Father crossed the room and bent over her. "What is it, Eugenia? What has happened?" His tone with her was gentler than I had heard in a long time.

"You will never forgive me. I will never forgive myself," she gasped between sobs.

Father pulled her up and led her to a chair, where she slumped, clutching at the handkerchief Father gave her.

"Oh," she moaned, "why did I not give her only a handkerchief, and a bit of toffee candy? Fool that I was..."

"Stop this, Eugenia." Father's voice was still kind, but it held authority. "Tell us about it. From the beginning."

And she embarked on her tale.

As I knew, Mother and Widow Hautzig were regular visitors to Sikram Ralatt, the new shopkeeper in town who sold potions and charms in addition to his regular merchandise of soap and herbal infusions. Mother had purchased a handful of charms from him, such as the one she'd wanted Father to tie around his ankle before one of his journeys.

"When Rose was home, Neddy," Mother said, wiping her eyes, "I happened to overhear the two of you talking. It was about her sleeping arrangements at the castle. When Rose said she was sleeping next to some unknown creature night after night, I became frightened for her. I was afraid it might be some hideous monster, or a wicked sorcerer, or ... a troll..." She looked at both of us beseechingly.

Father opened his mouth to speak, a confused look on his face, but Mother plunged on.

"I knew that if I spoke to Rose about it, she would brush me off, saying there was nothing to worry about. I was so upset that I confided my concern to my good friend Widow Hautzig, and she advised me to go straight to Sikram Ralatt, to see if he had some charm that would protect and help my dear Rose. So I did—I told Sikram Ralatt about someone close to me who was in danger, who slept in a room that because of some spell or another was impossible to light. I asked him what could be done. And it was then he sold me the flint and the candle."

We stared at her, Father in complete bafflement and I in horror.

"I ... I gave them to Rose," Mother went on. "I said nothing to her, leaving it to her own inclination whether or not to use them. But I confess that I hoped she would. That her curiosity would lead her to light the candle and look at who was beside her."

"Well, Eugenia," Father said, still perplexed, "perhaps it was not well to meddle, but I do not see..."

"You haven't heard the worst of it, not yet," Mother interrupted, tears spilling down her cheeks. "I ... I went into the village today and found that Sikram Ralatt is gone, disappeared without a trace, his shop cleared out, empty. As I went about, inquiring after him, I learned that he vanished the very day after Rose left. And what's more, there are all sorts of terrible rumors flying about the village. That he was ... he was..." Fresh sobs shook her shoulders. "Oh, what have I done, what have I done?!"