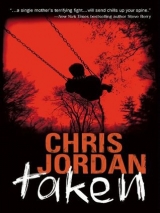

Текст книги "Taken"

Автор книги: Chris Jordan

Жанры:

Триллеры

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

2 THE METHODS

12 face down on the infield grass

The boy dreams that he’s lying facedown on the infield grass. Around him a game is being played. He can hear the crack of the bat, the chatter of the players, but he can’t see anything except the blur of grass in his eyes. The pungent green smell of it filling his nose. The boy can’t move—can’t make his arms and legs wake up—but he’s keenly aware of an urgent pressure in his bladder and knows that if he doesn’t get up soon he’ll pee his pants.

Bad idea to take a nap in the infield. What was he thinking? Now he’s half-asleep and can’t wake up and a batted ball might hit him, but what he’s really afraid of is embarrassing himself in front of the crowd. All the kids, the coaches, his mom. Eleven-year-olds don’t wet their pants. Not in public, anyhow. Not when they’re wearing uniforms. Plus, he’s supposed to be playing shortstop. What if a ball gets hit in his direction? Can’t make the play if you’re lying down, can you?

Below the murmuring chatter of the players he can hear his mother’s voice echoing from the dugout, exhorting him to get up. Really embarrassing, Mom telling him to wake up in front of all his friends. How did he let this happen? What was he thinking when he decided to take a nap on the grass, in the middle of a game?

Bladder hurts. The boy has to go, badly. He’s thinking if he can unzip his fly, maybe he can pee into the grass while he’s lying down and no one will notice. But when he tries to move his hands, his wrists get pinched somehow. Is someone standing on his wrists? Maybe they haven’t noticed him lying in the grass.

The boy concentrates on moving his hands to his waist, desperate to get his zipper down so he can relieve the pain in his bladder. He concentrates so hard that it hurts and the pain helps wake him up so he can force his eyes open.

His eyes are still blurred with sleep, so it takes a while to focus. And then when he does focus, it still doesn’t make sense. There’s a thick white plastic strap around his right wrist, cuffing him to a bedpost. He’s not facedown in the infield grass at all, he’s facedown on a mattress. A mattress that stinks of pee.

Not his bed, not his mattress. Can’t see all that well yet, can’t turn his head to look, but this doesn’t feel like his bedroom at all. Something wrong here. Something worse than wetting your pants in public. Something so terrible he doesn’t dare think about it yet, not until his head clears. Something that makes him want his mother very badly.

“Mom,” he calls out. “Mom, are you there?”

Right behind him, right in his ear, so close that it almost stops his heart, a stranger’s voice suddenly says, “If you don’t stop pissing the bed, kid, we’ll have to put rubber pants on you.”

Tomas starts to thrash on the bed, fighting the cuffs, and trying not to scream.

13 memory lane

Here in the suburbs, even the holding cells are upscale, more or less. My cell is a small, plain room, eight feet by eight feet, with no seat or lid on the commode, but the paint on the walls is fresh, and the floors have been scrubbed with pine-scented disinfectant. The bunk is narrow but adequate, rubberized and fireproof. No pillow, of course, because a distraught prisoner might stuff a pillow into her mouth and choke to death. No graffiti on the walls, no cockroaches, nobody there but me.

The lack of roaches is notable because I spend most of the first awful night on a trip down memory lane, and insects are included. One notorious Roach Motel in particular.

It happened like this. When we were first married, Ted and I drove across the country in his grandmother’s Ford Crown Victoria. That was her wedding present to us, a ten-year-old sedan with unusually low mileage because she was, as she told us, the “classic little old lady who drives to church on Sundays.”

In addition to being little and old, Clara was a lovely lady, and a wise one, too. “Drive until the road ends,” she advised us. “See everything you can along the way. Two weeks on the road, you’ll be bonded for life or applying for annulment. Either way it goes, at least you’ll know.”

In addition to the car keys, she gave us a thousand dollars for expenses. In other words she paid for our discount honeymoon with savings she could ill afford to lose. The Bickfords were not wealthy, or even particularly well off, and Grandma lived on her social security and the proceeds of her lifelong savings, which had already been tapped to help put Ted through college. When we protested, Clara fluttered her age-mottled hands dismissively. “I know how much I have in the bank and how long I’m likely to last. I did the math, Teddy. It’s a rather simple calculation, you know. Take the money, have fun.”

So we did. Piloting the boatlike Crown Vic down through the Amish farmlands of Pennsylvania and into the Ohio Valley, then swinging up for a glimpse of the Great Lakes, and on through Wisconsin and Minnesota and the Badlands of South Dakota. Where Ted insisted we go fifty miles out of our way to check out Wall Drug, whose signs had been haunting us for a hundred billboards along the way.

It was in Montana, Big Sky Country, that we came upon a bargain we were unable to resist. On a lonely two-lane not far from the Idaho border, roadside cabins were being discounted to ten dollars a night, double occupancy. Not a motel, cabins. Therefore old. Or as Ted said, vintage.

“Ever see It Happened One Night?” asked my film-buff husband as we opened the Crown Vic’s cavernous trunk and prepared to unload our cheap suitcases. “Clark Gable, Claudette Colbert?”

“Oh, probably, on AMC or something. Can’t remember.”

“Then you didn’t see it. If you saw it, you’d remember. Gable’s this reporter, Colbert is an heiress on the lam from the press. She’s hiding out by taking a bus cross-country and Gable finds her and pretends to help her get away, even though he’s a reporter, too. Anyhow, the two of ’em have to share a cheap roadside cabin, so Gable ties a rope between the beds, drapes a blanket over the rope and tells Colbert the blanket might as well be the Walls of Jericho, that’s how safe she’s going to be.”

“And was she?”

“By our standards, yes. I think they might have kissed.”

“You think? I thought you had all those old movies memorized, scene for scene.”

“Not quite.” He grinned and hoisted the suitcases. “After you, Miss Colbert.”

Inside, it wasn’t so easy to sustain the mood of frivolity. When Ted put the suitcases down, they slid to the far end of the cabin. The place smelled like moldy cheese. Very old and very moldy cheese. The bed sagged as much as the cabin floor, and the shower stall had stains that looked like something out of Psycho.

“If the guy running this place is into taxidermy, we’re out of here,” he said, and I agreed with a nervous giggle.

We were honeymooners, remember, so we propped up the old bed as best we could and tried to make use of it. At the crucial moment, Ted screamed. Rather a girlish scream, too. Seems a large cockroach wanted to explore his backside. We stayed the rest of the rainy night in the big back seat of that big Crown Vic, and by morning I knew for certain I would spend the rest of my life with Ted.

Best night we ever had together, until that first nervous night with our new baby, and that was a different sort of thing altogether. Revisiting both of those special nights is what gets me through this awful night in the holding cell. Because thinking about why I have been detained is more than I can bear. Although I have not yet been charged, Deputy Sheriff Terry Crebbin has made it clear that I’m suspected of kidnapping and murder. Which makes no sense at all. Where did they get that idea? Why would anyone think I would steal my own son and then kill the chief of police, who, in addition to being chief, was a good friend? If Crebbin knows, he’s not saying.

“Wait for your lawyer,” he sneers at me, not meeting my eyes. “People like you always have a lawyer.”

The way he inflects “people” makes it mean “bitch.” As far as Crebbin is concerned, I’m guilty. Charges have not yet been formulated by the county prosecutor’s office, so I’m to be held for the legal twenty-four hours.

“At least twenty-four hours,” Crebbin emphasizes. “A whole lot longer than that, if I have anything to say about it.”

“Fine,” I tell him. “I’m not going anywhere. Think what you like of me, Terry, but could you at least contact the FBI and tell them my son has been kidnapped?”

Crebbin stares at me then, as if inspecting the aftermath of a particularly gruesome accident. It’s obvious my very existence offends him. I should be in the freezer, not his boss. “The FBI has been notified. They’re not interested in your case.”

“They told you that?” I say, my voice rising. “You’ve been in contact with the FBI? What did they say, exactly? What do you mean they’re not interested? My son has been taken! He’s been held for ransom! They said they’d let him go but they lied!”

But Crebbin walks away without a backward glance, radiating malice. I’ve been allowed my phone call and used it to speak with Arnie Dexel, the attorney who handles legal and financial affairs for Katherine Bickford Catering. When I attempt to tell Arnie exactly what has occurred, he cuts me off, says he wants me to save the details for the criminal attorney he’s going to contact on my behalf. Terrific lawyer, top of the line. He mentions that attorney’s name but I immediately forget it, which will cause me great concern over the course of the long night in the holding cell. As if forgetting a lawyer’s name means the lawyer will forget about me.

All I have to cling to is Arnie’s promise that the lawyer, who is out of town on another case, will arrive like the cavalry by morning.

“Noon at the latest,” he says.

“Can’t you do something?” I beseech him.

“Sorry, Kate, but I really can’t. This is way out of my field. I’d be derelict in my duty not to find you competent counsel. Just hang in there. Help is on the way.”

Cavalry arrives tomorrow morning, he says. Probably be out before breakfast. In the meantime I must find a way to pass the hours without going completely out of my head. No exaggeration, my sanity feels in jeopardy. Thoughts are screaming through my brain like a runaway train. Nothing in my head makes any sense. The-man-in-the-mask, the-man-in-the-mask, the phrase pounds in my brain, making its own insane rhythm. Laughing at me. Whatever you do, don’t go in the basement. Some line from a cheesy horror flick. Maybe that’s where he got the idea of putting poor Fred Corso’s body in the freezer. Because it had to be the man in the mask, didn’t it? If he didn’t kill the chief himself, he knows who did, and used the body to frame me, and somehow make it look like I kidnapped my own son. But that doesn’t make any sense. Why would killing the chief of police make it likely that I’d invented the man in the mask? Because that’s what Crebbin thinks, isn’t it? That I’m making it up? Or is he holding something back, leverage to make me confess? Man in the mask, Tommy, Sheriff Corso, what’s the connection? There must be a connection. It’s certainly no coincidence that Fred Corso ended up in my freezer with a bullet hole in his forehead.

On and on and on, my thoughts colliding and tearing at each other, until finally I’m able to seize on the precious memories of our cross-country adventure in that great boat of a car, and so pass the night with my sanity more or less intact.

Morning brings breakfast, courtesy of McDonald’s takeout, but no lawyer. And Terry Crebbin has made it clear that the prime suspect—me—has exhausted her right to the telephone.

“One call,” says Deputy Katz, who has brought me breakfast in a white paper bag. She sounds somewhat apologetic, but will not budge. “Sarge says you only get one.”

“Do you have any kids?” I ask her.

She shakes her head. “Wouldn’t make any difference if I did, Mrs. Bickford. Sarge says no, that’s all that matters.”

“I’m not talking about the phone, Rita. Your first name is Rita, correct? I’m talking about my son. He’s been kidnapped. He’s been taken from his home, from everything he knows and loves. He must be scared out of his mind. Terrified. He’s eleven years old, Rita. You’ve got to help me. Call the state police, call the FBI, call anyone who’ll listen. Tell them what happened.”

For the briefest moment I’m convinced I’ve gotten through to pretty Rita, but it turns out to be wishful thinking. She hasn’t really been listening; she’s been studying me and has come to her own conclusion.

“If you think calling me Rita is going to help, you’re wrong,” she says, sounding deeply disappointed in me. “We’re trained to ignore stuff like that. Prisoners trying to get friendly, get you to do them favors. This patrolman in Bridgeport? He loaned his pen to this perp, thought he was harmless, perp says he wants to write a note to his mom? Perp stabs the patrolman with his own pen. In the eye. So you’ll just have to wait, Mrs. Bickford. Lady like you, somebody will show up eventually.”

Lady like me. What does that mean? Does this scrawny twenty-year-old really think she knows me? Did they teach her that in the academy? Lovely Rita, meter maid, how dare she? What gives her the right to judge me? Before I can pursue the matter, make her see things my way, she skedaddles, leaving me alone in the holding-cell area.

Famished, I devour the Egg McMuffin, chug down the lukewarm coffee. What does it mean that I haven’t lost my appetite? Ted died, I couldn’t eat for a week. Does that mean that my body senses that Tommy is still alive?

Ridiculous thoughts, impossible hopes. I cling to them until half-past noon, when the cavalry finally arrives.

14 killer mom

My idea of the perfect defense attorney is Gregory Peck in To Kill A Mockingbird. Tall, handsome, confident, wise and deeply convinced of his client’s innocence. Willing to face down a mob with nothing more than a firm jaw and his certainty of what is right. I don’t know what the actor was like in real life, but in that movie he was God with a law degree and a charmingly wrinkled suit.

I’ve got the wrinkled suit representing me, but that’s about all Maria Savalo has in common with Gregory Peck. She needs heels to clear five feet tall, can’t weigh more than a hundred pounds soaking wet. Lovely big dark eyes, but deeply circled—she looks a bit like Holly Hunter deprived of sleep for three days.

“Sorry about this,” she says, indicating the very expensive, very wrinkled Chanel pantsuit. “Slept in it last night and didn’t have time to change. Probably got B.O. and bad breath, too. Waiting on a jury. Very tense. Great outcome, though.”

“Innocent?”

“No, no. Client was guilty as hell and said so. This was the death-penalty phase. He got life,” she says triumphantly. Seeing the look of dismay on my face, Maria Savalo chuckles. “How to impress potential clients, huh? Show up looking like hell, talk about guilty clients. I’m very sorry, Mrs. Bickford. Let’s start over, shall we? You pretend I’m presentable because I usually am, and I’ll pretend I had a good night’s sleep because I often do.”

With that she juggles her briefcase and then formally shakes my hand. “This was your first night in jail, correct? My intention is to make sure it’s your only night in jail. There. How am I doing?”

I’m not sure how to respond, and the petite attorney doesn’t seem the least surprised. There are no lawyer-client consultation rooms at the station, so we make do with the holding cell. She plops down on the bunk, kicks off her heels and pats the space beside her.

“Take a load off your feet, Mrs. Bickford,” she says. “We’ll get started. I gotta tell you, when Arnie called me I let out a little shout when I heard your name. You catered my cousin’s wedding in Greenwich! Small world, huh? So even though we didn’t meet personally, your reputation precedes you. The food, I gotta tell you, the food was fabulous. Those little shrimp inside the pastry? Incredible! Unfortunately my cousin decided to dump that chump husband of hers three months after the wedding, but that’s not your fault, is it?”

I really don’t know what to say. My catering business is normally the second most important thing in my life, but right at the moment I could care less. Part of me knows that life goes on, that no matter what happens to me and Tommy, people will continue to get married, celebrate, host luncheons and banquets. They’ll care about food, and want to talk about it, no matter how many tragedies happen to other people—it’s human nature, how we survive. But right now I don’t even want to think about Katherine Bickford Catering, or what will happen to it if I can’t be there to run things.

Ms. Savalo senses my discomfort and reaches out to pat my hand. “Sorry. Down to business. Just had to let you know.”

“This is a nightmare,” I tell her. “I can’t seem to think straight. I keep thinking it can’t be happening, that the police think I killed someone.”

Ms. Savalo produces a tissue from her purse, evidently to offer me if I start weeping. I’m determined not to weep. Can’t fall apart now. Not with my son still missing. Have to save my falling apart for later.

“Maybe it will help if we formulate a chronology,” Ms. Savalo suggests. “Your version of events. Arnie gave me the highlights and I got some stuff out of the locals on the way in, but I really need to hear it from you.”

“I’m not sure where to begin,” I say. “The police don’t believe me, but my son was kidnapped.”

“Start with that,” she advises. “The kidnapping.”

I begin with the ball game and the field of green, rooting for Tommy. Who just lately has decided he wants to be called by his formal name, Tomas, and I’m sorry, but I haven’t fully made that adjustment, still think of him as Tommy. Anyhow, there we are, Little League, parents rooting, kids playing their hearts out. How harmless it all seemed, how comfortingly ordinary. Seems like a century ago, before everything changed. I tell her about waiting in vain for my son, returning home to find the man in the mask in the TV room. How he tied me up, terrorized me, knocked me out, stole my money, and then knocked me out again.

By the time I get to the freezer in the basement, Maria Savalo is nodding, as if to some music I can’t hear.

“No warrants, you say?”

I shake my head. “I let them in. Gave them permission to look in the basement.”

“No warrant,” she says, giving a little nod of satisfaction. “That’s good. That’s excellent. Now let me ask you a crucial question. Did you have any contact with the sheriff after your son was kidnapped? Did you by any chance call him?”

“No. The man in the mask, he—”

“We’ll get back to the man in the mask,” she says, cutting me off. “For now let’s concentrate on your use of the phone. Did you call anyone at all?”

Wait. There is something. I’ve forgotten all about returning Jake Gavner’s phone call. How did I manage to forget that?

“Not good,” is her response, after I fill her in. “You say that for the duration of the call, you gave Mr. Gavner no indication that you were under duress?”

“There was a gun pointed at me,” I tell her with a little heat, aware that my face is flushing.

“Of course there was,” she concedes. “So you did your best to convince Mr. Gavner that nothing was wrong? You told him your son was home?”

“I didn’t have any choice.”

“You convinced him?”

“I must have. He never called back. Not while I was awake. Later, the man in the mask told me I had messages, but I never had time to check them, let alone answer.”

Ms. Savalo purses her lips. “Tell me about that. You say you were injected with some sort of drug. Any idea what he used, this masked man?”

“All I know is it knocked me out.”

“How long did it take? Before you passed out?”

“I don’t know. A minute? No longer than that.”

“Good. I’m going to order a blood test. See if any residuals remain.”

I remember something else. How had I forgotten? What is wrong with my brain? “The police took blood from me when I came in.”

Ms. Savalo looks startled. “You gave them permission? Written permission?”

“No, not written. Terry Crebbin said if I didn’t stop shouting he’d have me gagged, so I shut up and let them do it.” Amazing, how an incident like that had slipped my mind, until she mentions blood, then it comes flooding back. My excuse is that I’d been trying to convince the cops to do something about my son, and not really paying attention to what they were doing to me.

“This is the deputy sheriff?” Ms. Savalo wants to know. “Crebbin, right? He threatened to gag you? So you complied?”

“Can’t stand the idea of being gagged.”

“Had your rights been read to you, regarding the blood sample?”

“I don’t think so.”

“This could be very important, Mrs. Bickford. Think again.”

“I’m not sure. I really don’t remember.” That’s the truth, but how could it be? How could I possibly forget something so crucial?

“But you didn’t sign anything? Scrawl your signature?”

“No.”

“Sure?”

“Positive.”

Ms. Savalo grins, and it makes her glow. Holly Hunter has nothing on her. “Better and better. Small-town cops. Felony murder, they get all excited. They’ve got a killer mom in custody, nothing else matters.”

“I’m not a killer mom.”

She looks at me with concern, radiating what seems to be genuine empathy. “My apologies, Mrs. Bickford. I was thinking out loud. Thinking like the cops, okay? We both know you’re not a killer mom, but they obviously think so, and it clouded their judgment. Which is good for us.”

I wish I felt good about it. Wish I felt good about something. As it is, the loss of my son feels like an unanesthetized amputation.

“What I still don’t understand is why the cops think I’m lying about Tommy getting taken, why would Crebbin think I made my own son disappear?”

Ms. Savalo studies me with her dark eyes, gives the impression she’s utilizing some sort of self-contained lie detector on me. The beam of truth. After a pause she says, “I can shed some light on that,” and opens her briefcase, handing me a sheet of paper.

“What’s this?”

“Photocopy of a legal document found in the sheriff’s breast pocket. That’s why it’s so blurry.”

“I still don’t get it,” I say, staring at the smudged image of what looks to be a postcard.

“It’s a ‘return receipt requested.’ Proof that you signed for a legal document on the twentieth of June. Looks like the sheriff’s department was serving you. Or that’s how it’s meant to look.”

I squint. “That can’t be my signature. I never signed this.”

Savalo’s smile is tight. “I bet you get lots of mail having to do with your business. Maybe you forgot.”

I shake my head. “I never got any legal documents. Not recently, and certainly not last week. Besides, what does this prove?”

“The cops think it proves that you were aware that your son’s natural mother was attempting to regain custody of her child,” she says, speaking very carefully.

My hands begin to tremble and the photocopy flutters to the floor of the holding cell. “That’s impossible,” I tell her, my voice sounding hollow. “Tommy’s mother is dead. Both of his parents died in a taxicab accident. In Puerto Rico.”

Ms. Savalo scoops up the photocopy. “The suit was filed by one Enrico D. Vargas, Esquire, office listed in Queens. I checked. He’s an attorney, duly registered in the state of New York.”

“I don’t understand.” Thinking that should be my mantra, so many things I didn’t understand.

“The petition to reassign custody was filed by a Teresa Alonzo, no address given, other than the lawyer’s office,” Ms. Savalo explains. “In the long run they can’t prevent us from discovering where she resides, but it will take a while. We’ll have to petition the court.” She pauses, locks eyes with me. “Are you absolutely sure you’ve never heard from Enrico Vargas? That Attorney Vargas hasn’t contacted you, or a lawyer representing you?”

“I’ve never heard of him,” I respond weakly. “Birth mother? This can’t be real. It can’t. Tommy’s parents are dead. They told us.”

“Who told you, Mrs. Bickford?”

“The adoption agency. Family Finders.”

“You saw the death certificates of the child’s parents?”

I shake my head. “I don’t recall seeing death certificates. We had no reason to disbelieve the agency. Ted checked them out before we applied, they were legit. Expensive but legal.”

“So you took them at their word, that the baby was available for adoption, free and clear. Nobody trying to assert custodial rights?”

“No, absolutely not.”

“Okay. We’ll check into that,” she says, tucking the photocopy back in her briefcase.

“What was Fred doing with that copy?”

“Fred? Oh, the deceased. No one knows for certain, apparently, but the supposition is that he went to your home to serve you with notice, or possibly discuss the possibility that you were about to be embroiled in a custody suit, or both. That he stumbled upon your plans to spirit your adopted child away from the authorities, attempted to intervene, and that you shot him. That to cover up the crime you invented a kidnapper. The man in the mask, as you call him.”

I can feel my jaw drop. “Oh, my God.”

“Obviously your position is that the abductor exists and that he’s attempting to frame you.”

My jaw snaps shut. “It isn’t my ‘position.’ It’s the truth! That’s what happened. Exactly as I told you. He took my son, he took my money. I assume he killed poor Fred.”

“Why would he do that? Frame you? Any theories?”

“I’ve been racking my brains,” I tell her. “No idea. Why would they care? They’ve got my son. They’ve got the money. Why bother going to all the trouble of framing me?”

After a pause, letting it soak in, Ms. Savalo says, “That’s interesting, the way you always say ‘they.’ I thought it was just this one guy in a ski mask?”

“He talked on his cell phone to others. Gave orders. I got the impression this was his business, kidnapping children and holding them for ransom.”

“Hmm. And we have evidence of the wire transfer. Not easy to trace through the Cayman Islands, but we’ll give it a shot. Okay, Mrs. Bickford. You’ve given me enough so I can have a conversation with Jared Nichols, the county prosecutor. Jared and I go way back, which may or may not be useful. At least he’ll give me a straight answer.”

She snaps shut her briefcase, slips into her heels and stands up.

“What do I do?”

“Wait,” she advises. “I’ll be gone an hour or two. Three at most. Then we’ll see?”

“See what?” I ask.

The attorney gives me a bright, reassuring smile. “See if I can work the old Savalo magic. Hang in there. Like the Terminator said, ‘I’ll be back.’”

A moment later I’m alone again.

After we got back from our honeymoon trip, Ted and I talked seriously about having children. We’d been having unprotected sex for more than a year and I hadn’t got pregnant, so a visit to the gynecologist was in order. I was put through a battery of tests—blood work, tissue samples, sonograms—and the results were not encouraging. Fibroid tumors. Not cancerous, but large enough to make pregnancy unlikely. I went through a long, painful procedure that was intended to reduce them in size. More than half of such procedures resulted in substantial reduction, supposedly, but it turned out I was in the unlucky half. No long-term reduction, no increase in the likelihood of impregnation. Most of the patients in my category eventually opted for hysterectomies. My option entirely. The fibroids were fertility threatening, not life threatening.

I offered to let my eggs be collected and fertilized by Ted’s sperm, in hopes of finding a surrogate mother. Ted ruled that out, in no uncertain terms. He was going to make a baby with me, in the normal way, or he wasn’t going to make a baby at all. Never mind all the legal and technical problems with finding a surrogate womb. And so we discussed adoption. Ted was especially enthusiastic about the idea of adopting—what did it matter of the child carried his DNA? It was raising a child together that mattered. Making a family.

As it turned out, finding an adoptable infant was nearly as difficult as dealing with the whole surrogate-mom issue, but of course we didn’t know that when we started. It helped that we weren’t insisting on a blond, blue-eyed baby. Hispanic origins were fine with us, although Ted was uneasy with the agencies who specialized in South American babies. Too many stories about poor women being more or less forced to sell their newborns, or having them stolen away and sold to intermediaries. Best to stick closer to home, where U.S. law applied. Eventually we found an agency with connections in Puerto Rico, were put on the list, and at last the great day arrived and baby Tomas came into our lives.

Could his mother still be alive? Had a woman calling herself Teresa Alonzo hired the man in the mask to take him back? But it didn’t make any sense—why hadn’t I been notified? Obviously if his birth mother wanted to reestablish contact, we could have worked something out. I wouldn’t have been so selfish as to deny my son contact with his birth mother. Would I?

Honestly, I don’t know how I would react. The notion that a birth mother might be involved is strangely reassuring, because if true it means that he’s still alive. But why empty my bank account? They’d have had no way of knowing that the money was intended for Tommy’s use eventually, would they? The man in the mask could access my accounts, pry into all my records, but he couldn’t read my mind, could he?

Truth is, I’m not sure of anything. I’ve never felt so lost, not even in those first nightmare days after Ted passed. Nothing is what I thought it was. The world is upside down, or inside out, and I’ve no idea where I fit in the scheme of things.

Except for this. I raised him, nurtured him, loved him to pieces, and this one thing I know: I’m the only mother Tomas “Tommy” Bickford has ever known.