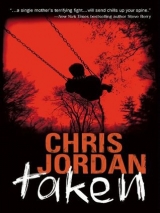

Текст книги "Taken"

Автор книги: Chris Jordan

Жанры:

Триллеры

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

44 what would shane do?

Rush hour starts early on the 287, and by the time we get to the Scarsdale exit it’s almost six-thirty. Fortunately Mr. Yap has been left at home, or else he’d be going nuts, because I’ve been playing backseat driver and Connie’s been pushing the Beetle for all its worth. Weaving in and out of traffic, using the breakdown lane, scooting through traffic lights with a blaring horn at my urging.

Should I be concerned about risking lives other than my own? Yes, but I’m not that good a person. All I can think about is Tommy, and what might be happening to him. What might already have happened. How every fiber of me wants to be with him right now, this instant, but I can’t. All because every truck in the world has decided to converge on this particular highway, at this godforsaken hour of the morning.

“What do we do when we get there?” Sherona wants to know. “You got a plan?”

“I don’t know,” I tell her. “Rush in the place and shout the medical equivalent of ‘stop the presses,’ I guess. If we even have the right place.”

“I feel good about it,” says Connie, trying to keep my spirits up as she hunches over the wheel like a NASCAR driver. “The ambulance was on 287, the clinic is just off 287, where else could he be going?”

“Could be heading to the Sawmill,” I fret. “From there he could go anywhere.”

“We’ll get there, check it out,” Connie promises. “One more light, and then we turn left on Fennimore, then the second right.”

After what seems an eternity—I’m debating whether to get out and run—at last we’re on a boulevard that isn’t clotted with commuters. Professional offices and plazas, all beautifully landscaped.

“It’s here somewhere,” Connie says as I crane my neck, searching.

Sherona spots the sign before I do, and Connie screeches into the tree-shaded parking lot of the Scarsdale Transplant Clinic, an ultramodern ground-level concrete structure with darkly tinted windows, the whole structure painted in shades of pastel that fail to make it welcoming. In the center of the wide swath of perfectly manicured lawn, a heliport pad with a shiny gold MedEvac helicopter strapped down with what look like silver bungee cords.

At this hour there are only a few vehicles in the lot—a matched pair of Mercedes coupes and a Lexus sedan—taking up the slots assigned to staff. The place is utterly quiet, no sign of life. Except for the telltale doctor cars, it doesn’t even look open for business.

“What now?” Connie asks, sounding much less confident than she did while fighting us through traffic.

“Sherona, how about you try the front desk,” I suggest. “Use your powers of persuasion. Tell ’em what we know, see if it does any good. Connie and I will circle around the back, see if we can find a back way in.”

“‘Powers of persuasion,’” says the big woman as she eases her weight out of the tiny Beetle. “I like that.”

She struts away like a drill sergeant looking for troops to rally.

Around the back we find a hospital loading dock with an ambulance in the slot.

My heart slams and my mouth goes dry.

“Jersey plates,” says Connie, sounding thoroughly discouraged.

“Doesn’t mean anything,” I tell her. “Plates can be swapped. You notice the doors?”

“What about them?”

“See where it says Beacon Medical Transport? Those are magnetic signs.”

I vault out of the car, approach the ambulance. It’s a big, boxy vehicle with orange-and-white stripes that look very familiar. A quick inspection reveals that the magnetic stick-on signs cover the logo for Hale Medical Response.

We’ve found it. Against all odds, we managed to track the monster to this very place.

My heart lifts. At the same time my anxiety level spikes so high it feels like my head is about to explode. And my knees, well, they seem to have dissolved, leaving me with legs like limp spaghetti.

This is it. Somewhere inside this building, my son is waiting. Alive or dead, I’m going to find him in the next few minutes.

“Where are you going?” Connie wants to know, hurrying to catch up.

“He’s here,” I say.

“We should call,” Connie suggests. “Alert the cops.”

My hands shake as I hand her the cell phone.

The loading doors, I soon discover, are bolted from the inside. Pounding with my fists produces nothing but a dull thump. Running around the corner of the building, I’m confronted by mirror-tinted plate-glass windows that extend from the roofline to the ground. Crazy with fear, I search the ground for a rock. Wanting to smash the hateful glass. Finding nothing but grass and imbedded paving stones.

What would Shane do?

“Connie! Your keys!”

Without a word, Connie hands me the keys to the Beetle.

“Stand back,” I tell her, and run to the car.

The engine starts instantly, but the little car has a standard transmission, and the first time the clutch is popped the engine stalls. Grinding the starter, begging it to go. The engine chugs to life and I ease it into first gear and run up over the curb, onto the pristine lawn. Gathering speed across the lawn, I’m in third gear by the time the building looms. Somewhere in my peripheral vision, Connie is raising her arms, her mouth as round as that Munch painting of The Scream, either cheering me on or shouting for me to stop, or maybe both.

What I’m thinking, as the little car crashes through the plate glass, is that my friend Connie will be mad at me, and then the rear wheels catch and I’m thrown hard into the steering wheel.

Then nothing, blackness.

When I come to, bells inside the building are ringing like a giant alarm clock. The windshield has been reduced to diamonds that litter the dash. I can feel them in my hair, particles of shattered glass, and my face is hot and wet. The front air bags have deployed, pinning me to the back of the seat, which is now in the rear of the vehicle. Can’t move. Can barely breathe, a great pressure on my chest and lungs.

And then Connie is there, frantically reaching through the broken side window and trying to pull the air bags away from me.

“The door is jammed,” she informs me in a strangely calm voice. “You’ll have to scrunch through the window.”

Somehow she gets her hands under my arms, pulling and guiding me, and I’m popping out through the shattered window and both of us fall to the floor with a great woof! of expelled air.

“You’re bleeding,” she says, panting as she touches my forehead.

“Sorry,” I say. “Your poor car.”

“Can you stand up? Anything broken?”

My ribs hurt like hell, but a wobbly version of my legs seem to be functioning. Looking around, my vision is blurred but I can make out that we’re in some sort of conference room. Smashed chairs and tables, a lectern gone vertical, a torn projection screen hanging like a sparkly white rag. And the alarms making the insistent all-hands-to-battle-stations ring…ring…ring as if somewhere a nuclear-reactor engine is about to melt down.

Then, bursting into the room, a young security guard who can scarcely believe what he’s seeing.

“My God, what happened?”

With Connie holding my arm to steady me, I’m crunching through the glass fragments, heading for the guard.

“The police are on the way,” he tells us. “What happened? Did the accelerator stick?”

He thinks it was an accident, and I see no reason to disabuse him of the notion, particularly since he’s got a holster on his belt and, presumably, a gun.

“My son,” I tell him. “Surgery.”

Since he still seems befuddled by the shock of having his building invaded by a Volkswagen Beetle and a couple of suburban females, I hurry past him, out into a brightly lit hallway with slick, shiny floors. Behind me I hear Connie talking urgently to the guard and I’m thinking, Isn’t that nice, she’s taking care of business, good old Connie.

Floating into the hallway. Somewhere from the back of my mind, or maybe the inner ear, comes a single, high-pitched musical note. A dreamy violin with only one thing to say. Very odd, but sort of pleasant.

“Tommy,” I want to say, but my mouth doesn’t seem to be functioning for the moment.

From somewhere in the building, a flat popping noise. Somebody lighting firecrackers? Don’t they know it’s not yet the Fourth of July? Or is it? Have I missed the Fourth?

Trying to recall what day it is, exactly, when a man in green surgical scrubs hurries toward me, gowned and masked. There may be spatters of blood across his chest, I can’t be sure. My vision is still off, as if some internal part of me remains tilted inside the wreckage of the car.

“Are you a doctor?” I demand, trying to keep him in focus. Good, mouth working again.

He shakes his head, eyes on the ruined room behind me. “Nurse,” he mutters, and keeps on going.

Probably thinks they’re being invaded by an outraged patient, a transplant failure gone postal.

Then I’m jogging along the hallway, having trouble keeping upright. Something wrong with my sense of balance. The alarm bells have ceased, and in the distance I hear the whoop-whoop of a siren. Strangely, it sounds like it’s going away, but all of my senses are distorted, and for all I know the siren is actually inside the building.

That’s when I notice how hard it is to breathe. Something wrong inside? Can’t tell. Maybe the air is too thin. Very rarefied brand of air they have here in Scarsdale. Lurching around a corner, it feels like I’m attempting to manipulate a very difficult marionette, one whose limbs do not correspond to the strings.

Ignore it. Find Tommy.

“Tom-eee-eee-eee…”

Is the echo in the hallway or inside my head?

The wall steps out and slams me. Whoa. Keep it vertical, girl. Miles to go before you sleep. Somewhere in these tilting funhouse hallways your boy is waiting. You can almost see him sitting up in his hospital bed, a big grin on his beautiful face, saying, “Hey, Mom, what’s the haps?”

Did Tommy say that? Did I hear him? Must be close. Just a little farther on down the road.

Somewhere nearby, or a million miles away, a pair of doors beckon. The double doors to an operating room. On E.R. the O.R.’s always have double doors. Try saying that three times quick. Unless I’m seeing double, which is entirely within the realm of possibility. Or triple, is there such a thing as triple doors? Glass walls, lightly tinted, make me feel like I’m floating outside a space station, looking in. Carts of surgical equipment lurking in the tinted shadows behind the glass. Some of the shadows moving—no, those are people, not shadows. What are they doing? Why are they hiding behind the glass?

In the center of the glass-walled room, a pool of light. And there, stepping into the light, another figure wrapped into a green surgical gown, weird magnifying glasses that make him look really dorky, and in his gloved hands, a glint of light.

“Scalpel, please.”

No, no, no.

Must get through the doors. Must grab the hands of the man in the silly green gown, make him stop whatever it is he’s intent on doing.

Yell at him, Kate. Make yourself heard.

“Gahhh!” and then I slam through the doors and spin into the glass-walled operating room and the spin part gets out of control and the floor comes up and kicks me in the butt.

Looking up into lights so bright they make my head hurt. Can’t breathe. I try to say something but all I can do is gurgle like a baby, isn’t that odd? Isn’t that strange?

Then some icky green rubberized fingers are inserting themselves into my mouth and I’m no longer even trying to breathe—too much trouble—and a small, insistent voice in the dimmest part of my brain is telling me to stop struggling because I’m already dead, dead, dead.

45 get you a flyboy

Shane is waiting to greet me on the other side. “Hi, Kate,” he says in a husky voice. “Welcome back.”

How strange is this? I’m thinking. If anybody’s waiting to greet me it should be Ted. I’ve only known Randall Shane for a few days and it’s not like I’ve fallen in love with him, right? Not possible, too many important things on my mind, although I can’t seem to recall what, exactly. So what’s Shane doing here—wherever “here” is? And then I feel the gurney under me and background noise of life in tumult and the first word out of my mouth is Tommy.

“You should rest,” Shane advises, patting my hand. “You had a collapsed lung.”

“What about Tommy?”

The world slowly comes into focus. Doctors and cops rushing around, and a couple of suits that could be state police detectives or FBI agents, all of whom seem to be studiously ignoring me. So what’s new? Waiting at the end of the gurney, Connie and Sherona are giving me little encouraging waves. Deferring to Shane, apparently.

“It’s amazing what medical science can do,” Shane tells me, ignoring my question. “They put a tube down your throat and inflated your lung like a balloon. They tell me collapsed lungs are common in front-end collisions.”

Shane, with a huge chunk of white gauze taped to his head and two black eyes that make him look like a mournful raccoon.

“He’s dead, isn’t he?” I say. “We were too late. Tommy’s already dead.”

Shane grimaces and keeps patting my hand, as if not sure what to do, or how to respond. He glances at Connie, who bursts into tears and then throws herself on me.

“Hey!” Shane exclaims, backing away. “Careful!”

“Terrible,” Connie mumbles, embracing me. “Just terrible.”

“I want to see him,” I say, forcing myself up from the gurney. Woozy but able to breathe, more or less. No tears. I feel frozen emotionally, unable to react. “Take me to Tommy.”

As the world reorients itself around me, it becomes obvious that I’ve been lying on a gurney outside the clinic O.R. Apparently I stumbled through the doors just before passing out, and the attending surgeon quickly determined what was wrong and fixed it. Whether or not he saved my life is questionable, as a single collapsed lung is not usually fatal, at least in the short run. Everybody keeps assuring me I’ll be fine.

“Where is he?” I demand.

Shane thinks I mean Cutter, the man in the mask. “He got away. We don’t know how, exactly, with all these cops and agents converging on the place. They’re conducting a thorough search of the building and grounds, but he’s gone.”

The figure in the green surgical scrubs.

“I saw him in the hallway,” I tell them as it all comes flooding back. “Said he was a nurse. It was him. I couldn’t focus, but it had to be him. He took the ambulance. That was the siren.”

“You have to tell the agents about this,” Shane advises.

“After I see my son.”

Frankly, it no longer matters to me, what happens to the man in the mask. Arresting him won’t bring Tommy back. I simply don’t care about him, one way or another.

Shane and Sherona are guiding me down the hall, shielding me from the harried cops, who look grim and impatient and much too busy to bother with the emotional needs of mere civilians. Connie hovers fretfully, tears freely streaming down her narrow face, dripping from her chin.

“Did they do it?” I want to know. “Did they save the other boy?”

“You stopped ’em,” Sherona says. “Hit the building, all the bells went off, they stopped whatever it is they were doing. Right after is when he started shooting.”

“Shooting?” I vaguely recall thinking about fireworks.

“One of the doctors, he’s been gut shot. Guess what happened, he tried to stop the man from running away.”

It’s all too complicated. My entire being is focused upon one simple goal. See Tommy, hold him in my arms, tell him how sorry I am that I wasn’t able to save him.

After that, I couldn’t care less.

They’re guiding me into a small recovery room when Shane says, “Kate? There’s something you need to know before you go in there.” He hesitates, looks helpless. “Something that needs to be clear.”

I’m in no mood for this, for trying to shield my feelings. I haven’t got any feelings so there’s nothing to protect. “Just tell me, Randall. Quickly.”

“Your son is brain dead.”

“Of course he’s brain dead,” I say angrily. “They took his heart.”

“No,” says Shane, holding me back from the room. “No, no, his heart is still beating. He’s breathing on his own, too. But the nurses just gave him a brain scan. There has been terrible damage, quite recent. Nothing anybody can do to bring him back. He’s gone, Kate, I’m so sorry.”

I wrench my arms away from Shane and run into the room. Smells faintly of disinfectant. Stark lights glinting off tile floor and walls. In the center of my vision, a gurney. And lying on the gurney, a small figure with his head carefully balanced on a special supportive pillow. Not moving, not reacting. Not dead, exactly, but not fully alive, either.

I fall to the floor, weeping. Ashamed of myself.

Connie hugs me from behind. “Oh, Kate. I’m so sorry.”

“You don’t understand,” I bleat.

“I know, I know.”

“That’s not Tommy,” I explain, dragging myself to my feet, and Connie with me.

Shame on me, but I’m crying tears of joy.

“I don’t understand,” says Dr. DeMillo, looking perplexed.

A vain-looking man with a very expensive hair weave and beautifully capped teeth, DeMillo is one of the clinic partners. A surgical specialist in diseases of the liver and kidneys, he had been preparing to assist Dr. Munk with the hastily scheduled heart transplant, and apparently still believes the recipient was somehow related to a Very Important Person in the State Department. Whatever that might mean. I’m having trouble keeping all the partners straight—there are five at the clinic—but I’m aware that a Dr. Stanley Munk was the one who was shot, and who evidently had some sort of prior relationship with Stephen Cutter. The fact that Munk is expected to survive is apparently due entirely to DeMillo, who performed emergency surgery to repair an artery torn by a bullet fragment.

“Stan said one boy was breathing on his own and the other was on the respirator. That they had run a preliminary scan and one had recently suffered irreversible brain damage. Gone from vegetative to brain dead. I naturally assumed it was the donor. Neither patient had been prepped. The nurse accompanying the brain-dead boy was very upset. It’s been so confusing. We just assumed that—”

“Doesn’t matter,” I interrupt, waving him off. “Let me guess, the donor, the boy on the respirator, he was still in the ambulance?”

DeMillo looks started. “As a matter of fact, yes. We were on our way to bring him into the building for evaluation when the explosion happened. I mean the car crash. I thought it was an explosion. Sorry, I guess that was you.”

Ignoring DeMillo, I turn to Shane and give his arm a squeeze. “Get it?” I ask. “Do you see what happened?”

“Yes,” he says. “Cutter still has Tommy.”

“I let him walk right by me. And before, when Connie and I first got here, I was standing right next to the ambulance while Tommy was inside.”

Can’t believe I was so stupid. Why hadn’t I thought to look in the ambulance? Why had I assumed Tommy was already in the building?

“Where are you going?” Shane asks, hurrying to catch up.

“I think I know where he’s headed,” I tell him. “How long was I out?”

“Not sure exactly,” he says, consulting his watch. Squints as if he’s having trouble seeing with his trauma-blackened eyes. “I got here almost exactly when the crap hit the fan. Or rather when you hit the building. You were unconscious for an hour or so, is my best guess. They had to sedate you to get the tube down your throat.”

“Sherona! Do me a favor?”

“If I can.”

“Find out if there’s anyone here who can fly that helicopter. Be nice, and if that doesn’t work, threaten to sue. Got it?”

Sherona grins. “Yes, ma’am,” she says. “Get you a flyboy.”

46 he said goodbye

My idea of transportation involves wheels on the road, or the rails. To my way of thinking, flying is about as glamorous as falling. Both involve speed, fear and the uncertainty of a sudden stop. When Ted surprised me with a three-day getaway for our first anniversary he learned the hard way that “small aircraft” and “Kate Bickford” should never appear in the same sentence. The flight down to Fort Lauderdale was okay—I was determined to make it okay—mostly because if you try really hard, you can pretend that a 757 is a big fat train compartment in the sky. It’s important never to look out the window, and if the ride gets bumpy, think of frost-heaves on the road. Plus, I was deliriously pleased that my handsome husband hadn’t forgotten after all, that his baffled looks in the preceding days were feigned. At the time we were basically broke, paying off school loans and a car payment, so our destination wasn’t exactly a five-star resort, but it was in the Caribbean, so who cared? Palm trees, steel drums, reggae in the moonlight—until Ted gently informed me that steel drums and reggae were Jamaica and we were heading for the Bahamas, a scant fifty miles off the coast of Florida.

I didn’t care where we were going as long as we were going there together, and I was so impressed with his ability to surprise me that at first I thought the little airplane in Fort Lauderdale was part of the joke. You’re kidding, right? That’s not the real thing, it’s a model airplane! Ha, ha, ha. No, it’s a six-seater Cessna, honey, and the flight takes less than thirty minutes. As soon as we take off you’ll be able to see our destination. It’ll be fun, all part of the adventure.

Flying in the clinic’s helicopter—a Bell 407 EMS, whatever that is—makes the Bahamas flight seem like a bike ride to the end of the block. My first helicopter experience and, I hope, my last. Can’t get airsick because to be sick you have to have a stomach and mine has been left somewhere far below. We’re crossing a swath of Connecticut at a hundred and fifty miles per hour and the roar of the Rolls-Royce turbine is so loud you have to wear shielded headphones.

Shane is in the jump seat behind me. I hate that they call it a jump seat, but his voice in the headphones is totally calm.

“The local police have been dispatched,” he tells me. “The SWAT team won’t deploy until the situation is accessed. They’ve been informed that the suspect has your son, and that any police presence may set him off.”

“What does it mean ‘until the situation is accessed’?”

“Means they’ll keep out of sight until told otherwise. Nobody wants a hostage situation, Kate. That much is clear.”

At the moment I’ve lost all faith in the ability of the authorities to deal with the man in the mask. I know he’s got a real name, but I can’t seem to lock onto it—he’s still the man in the mask to me. Ski masks, surgical masks, whatever it takes, he’s got a way of making himself invisible when necessary. He managed to slip away from about fifty cops and agents converging on the clinic, all because nobody thought to stop an ambulance with emergency lights flashing. So the idea of a SWAT team doesn’t exactly thrill me. Anxious snipers, a gun battle, hostages down, it all adds up to a nightmare.

Sherona and Connie have been left behind in Scarsdale, not required on this part of the mission, and to be truthful neither seemed all that thrilled about a helicopter flight anyhow. Maria Savalo has promised to rendezvous with us on the ground as soon as she can get there, to handle any legal problems that may arise. My indictment will surely be dropped as they develop new evidence with a new suspect, but I’m not out of the woods yet. Apparently an understanding of what actually happened will take a while to seep into the various bureaucracies, from the Fairfax P.D. to the state prosecutor’s office. I’m no longer killer mom but remain a “person of interest,” whatever that means.

Considering the time of day, we’d be at least two hours away by car, crawling in morning traffic around the urban centers. As the crow flies—or rather as the Bell 407 flies—we’re less than forty minutes from our destination. A rough calculation means there’s a chance we’ll arrive before he does, even though he had a ninety-minute head start. That’s what I’m praying for, to be there when he arrives, before he has a chance to set up whatever sick scenario he has in mind.

The state cops are on the lookout for the stolen ambulance, but my own feeling is, he’ll have new wheels. Something faster, more maneuverable. Van or a pickup. Maybe a station wagon with tinted windows. Whatever he needs to blend in while transporting Tommy to the scene of the standoff. Because that’s where all of this is heading, now that his cover has been blown, his identity shared with every law enforcement agency in the Northeast. As a military man he’ll understand about snipers, he’ll have made preparations. Spider-holes, tunnels, who the hell knows what has taken shape in his sick and desperate imagination?

One thing I know for sure: A man willing to steal a heart from a living boy is capable of anything.

As for Randall Shane, he worries me. The man should be in a hospital bed, under observation, but he insisted on signing himself out, and now he insists on accompanying me. Says he’s fine, no problem, but his eyes have a funny way of going out of focus, and when he walks he looks like a deep-sea diver maneuvering in lead boots.

In my headphones his husky voice says, “You’re convinced he’ll go home. Was it something he said?”

“No. His wife. He left her locked up in the house—or that’s what he thinks. Besides, where else can he go?”

The question is rhetorical, of course. There’s no correct answer, just a gut feeling, and obviously my gut feelings are far from infallible.

As we approach New London, Shane begins to confer with the pilot about strategies for approach. The navigational equipment can direct us to a street address, but it’s not like he can land the thing on a rooftop. Maybe in the movies. In reality there are radio towers and poles and power lines and crosswinds to be taken into account—a wide-open space is required. Plus, if we land too close, the sound of the helicopter will give us away.

“How about there?” Shane asks, pointing. “Would that work?”

“Baseball field,” the pilot says. “Perfect.”

And then the bottom drops out and we’re plummeting. Feels like we must be crashing but the pilot seems calm, so I stifle the shriek in my throat and concentrate on not throwing up. At the last moment we slow down, rising slightly—my stomach suddenly finds me—and then, with a slight bump, we’re down.

Shaking like a leaf, I unbuckle the harness, take Shane’s outstretched hand, and find myself standing in the outfield grass. The ground seems to be moving and Shane has to grab hold to keep me from falling down.

“Take it easy!” Shane shouts as the turbo winds down.

He’s a little rocky himself, and in the end we hold each other up while the pilot grins and shakes his head—amateurs.

“This is a Little League field,” I tell Shane. “I bet he played here.”

“Who?”

“The other boy. Tommy’s brother.”

Spooks me out, thinking about it, so I shove it out of my mind and concentrate on the mission at hand. The authorities are under the impression that I’ll be standing by in case there are hostage negotiations, but that’s not what I have in mind. I intend to be waiting in Lyla’s kitchen when her husband comes marching home. Knowing I can’t be dissuaded, Shane wants to be there, too.

“Which way?” I ask a bit too loudly, my ears still ringing from the helicopter noise.

“Three blocks east.” Shane takes my arm, supposedly to guide me but really to steady himself.

If I knew the Vulcan nerve pinch I’d render him unconscious, leave him sleeping safe and peaceful on the outfield grass. Then again, he’s probably thinking the same about me, although to my way of thinking a collapsed lung isn’t half as serious as a concussion. The cracked ribs hurt like hell, but it’s only physical pain. Nothing compared to the yawning emptiness I’ve been fighting ever since learning that I’d been within a few feet of my son—right there in the ambulance, you fool!—and that I might have blown my last good chance.

Please be alive. That’s my three-word prayer, my mantra, the faint chorus of hope that keeps me going.

We’re on an ordinary sidewalk, the kind with cracks that will break your mother’s back, but the concrete feels spongy under my feet. Shane isn’t faring much better—no words of complaint, but every move is a wince of pain. An observer might suppose we’re an elderly couple shuffling along on our morning walk, holding each other up. The holding-each-other-up part is true enough, and our progress seems agonizingly slow. I suppose we’re moving at a more or less normal rate, but to me it feels like we’re struggling every step of the way. Running in slow motion through deep sand with a tidal wave poised to crash over us.

Three blocks, but it feels like a journey to the end of the earth. At last the trim little house with the white picket fence comes into view. No vehicle in the street or driveway. Looks like we’re going to make it before Papa Bear comes home.

“Don’t turn your head,” Shane cautions. “Can you see that hedge?”

He means the hedge at the other end of the block. I squint, and bring into focus the figure of a man in a blue flak jacket, crouching behind the hedge.

“They’re covering the house from both sides,” Shane says.

When we’re about a hundred feet from the house, the commander of the local SWAT unit steps out from behind a tree and tries to wave us off.

“Do they know who I am?” I ask Shane.

“Not sure,” he says. “They might. Or they might think we’re from the neighborhood.”

“Will they shoot us?”

He shrugs. “I seriously doubt it.”

“Good enough for me,” I say, and steer him around the picket fence, into the yard.

All the curtains are drawn. The house looks sleepy somehow, as if waiting for something, or someone, to wake it up.

“What’s your plan?” he wants to know, keeping his voice low.

“Get in the house.”

“Yeah, but how?”

“Around the back,” I say. “There’s a bulkhead door.”

Behind the adjacent home, barely in our line of sight, men in camouflage gear have assembled, sniper rifles at the ready. More furious arms wave, trying to warn us off. We studiously ignore them and proceed to the bulkhead. It’s not fair to these brave and dutiful men, but I can’t help thinking about the SWAT unit at Columbine, waiting until all the killing had been done before they send a man into the school. Following procedure, even if it means a courageous teacher bleeds to death while they “access the situation.”