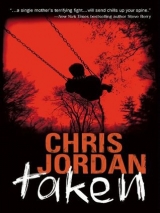

Текст книги "Taken"

Автор книги: Chris Jordan

Жанры:

Триллеры

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

The boy shrieks gleefully, then buries his face in his father’s ample midriff, as if hiding from the world.

We wave and turn away. Spatters of cool rain hit my face, and thunder rumbles in the distance.

“God is bowling,” I say. “Tenpins in heaven.”

“What?”

“My mother used to say that.”

“Uh-huh. We need the rain, I guess.”

We’re crossing the street when a car pulls out from the curb. I’m not really paying attention, other than to note that it’s silver or gray, and looks like a new model. Shane, however, is alert, and that’s the only reason I’m alive, because when the car suddenly accelerates with a screech of rubber, he scoops me up in his long, strong arms, and flings me out of the way.

I land on my back and get the wind knocked out of me, and sense the whoosh of the tires just missing my head. But there’s a horrible sound of flesh on metal, and then Shane is flying over the hood, spinning through the air, and he comes to earth with a sickening crunch, headfirst.

Behind me, Mike is shouting, but I’m not really paying attention. All I can think about is Randall Shane, and the blood, and the way he lies as still as death.

37 a sleep so deep

Four miles from the scene of the hit-and-run, with sirens keening in the distance, Cutter pulls into the breakdown lane, opens the door and pukes his guts out, spattering the pavement. Not because he’s revolted by what he’s done—assault with a motor vehicle is a whole lot less visceral than slitting an enemy’s throat—but because he lost control of the situation. Because he allowed himself to react without thinking.

He’d been parked there at the curb, engine quietly ticking over, debating whether or not to be on his way. So far as he was aware, no one in Sussex had any connection to him. Whoever Supermom was visiting up there, it was not likely to be anyone who could point her in the right direction. She and her hired hand were spinning their wheels. Maybe the tall, lanky dude was intentionally running up the bill, taking her on wild-goose chases for billable hours. Wouldn’t be the first time that lawyers and private dicks conspired to strip a client of assets.

Almost made him feel sorry for the lady.

And then, incredibly, just as Mrs. Bickford and company were about to leave, a familiar figure had appeared in the entrance of the tenement building. It took precisely one heartbeat for Cutter to recognize Big Mike Vernon—hadn’t seen the guy in eight years—and to understand with sickening finality that all his elegant survival plans had just been blown sky high.

If they knew enough to seek out and question Mike, then they were already onto him, or soon would be.

In that moment he simply reacted, pedal to the metal. He’d felt the collision, seen the investigator airborne, flying over the fender, but was less certain about the woman. Maybe he’d hit her, maybe not. Didn’t dare turn around and attempt to finish the job, not with Big Mike present and screaming for the cops. The guy looked huge and slow, but the glacial appearance was deceptive. When he had to move, Mike was more than capable. Best to flee the scene before the cavalry arrived.

Not that killing Mrs. Bickford would put the cork back in the bottle anyhow. The knowledge was out there, no doubt already passed on to lawyers and prosecutors and various law enforcement agencies. He had to face the fact that for all his elaborate precautions, he’d somehow been identified, that cops would be looking for him in the next few hours. So, a major alteration in the plans. The surgery would proceed, of course—there was no turning back from that—but he had to stop entertaining the notion that he’d be able to return to his life as a devoted father, that they’d all live happily ever after, he and Lyla and Jesse.

Wasn’t going to happen. The ever-after was already here.

You’re a dead man, he tells himself. Deal with it.

After rinsing out his mouth with a bottle of warm springwater, Cutter takes a deep breath and carefully maneuvers the Caddy back into traffic. Have to ditch the vehicle at the first opportunity. But not before he returns to the boatyard. Not before he prepares Mrs. Bickford’s boy for what must come.

Sad but true. The boy has to be sacrificed. Tomas will be sedated—Cutter doesn’t wish to cause him any discomfort—and then at the appropriate moment an ice pick will render him brain dead, and he will begin the short journey to the end of his life.

When Ted passed away I was sitting in the hospital cafeteria, sipping a cup of coffee, munching on a chocolate-chip cookie and mindlessly watching CNN. Talking heads jabbering about politics or crime or maybe something inane, who knew, since the volume was blessedly down. And I was having trouble holding a coherent thought in my head, not having slept in more than twenty-four hours. Ted had been through about four crash codes in that time period, but when I’d left him he’d been resting peacefully, and it was my intention to return to his bedside and stay with him for however long it took, days or weeks, it didn’t matter. That’s what I tried to tell myself. The truth is that knowing he was dying didn’t mean I was ready for it to actually happen. Just as I hadn’t been willing to accept that his form of lymphoma was a death sentence.

At first I’d wanted him home, made comfortable with hospice care, so it would happen in familiar surroundings, but he’d said no. Afraid of spooking Tommy by letting death into house. If the boy were older and could comprehend what was going on, maybe, but how would a child react at four? Why risk inflicting more trauma than necessary? Ted wanted Tommy to remember him alive and happy, not in pain and dying. Best to stay under medical supervision, where they knew what to do, how to cope with the terminal cases.

Trouble was, I didn’t know how to cope. And to this day I’m convinced that Ted chose his moment, sending me away for coffee and a cookie while he prepared to leave his poor, ruined body.

Randall Shane is different, but somehow the same. Not a husband or a lover, but most definitely a friend. And here I am, keeping vigil, at least for a few precious minutes.

“Mrs. Brickyard?”

It feels silly and a bit stupid answering to the wrong name—must have been Mike Vernon’s doing, as they loaded Shane into the ambulance—but I can’t bring myself to correct the E.R. doctor, just in case he’s been tuned in to the local news.

The man in the white coat looks a bit like Doogie Howser, M.D., but he’s all business, with none of Doogie’s sympathetic bedside manner. Only on TV, I guess. Impossible to say what he’s about to impart, as his expression gives nothing away.

“I’m Dr. Vance,” he announces, then checks his notes before continuing. “Mr. Shane is badly concussed, as we assumed.”

“He’s alive?”

“The patient hasn’t regained consciousness, but vital signs are stable for the moment. Head injuries, these first few hours, are crucial. We’ll be monitoring his condition, ready to intervene if his brain swells.”

“The way he hit, I thought sure he broke his neck.”

“X-rays showed no serious damage to the spinal column,” the doctor says, ticking off the injury list. “Most of his ribs are broken. Various scrapes and cuts. Let me see…his kidneys may be bruised. He sustained a hairline skull fracture that may eventually require surgery. We’ll make that decision later. Are you next of kin, by any chance?” he asks, indicating his medical notes.

“There are no next of kin, as far as know.” I fumble in my purse for Mario Savalo’s business card and give him her number, which he dutifully writes down.

“And Ms. Savalo would be?”

“His employer. May I see him?”

“If you like. I must warn you, Mr. Shane is nonresponsive. What we’d expect at this juncture, with a severe blow to the cranium. Oh. The police are on the way. They’ll want to interview you about the accident. I understand it was a hit-and-run.”

“Yes, it was. I’ll be in the ICU if anybody needs me. Thank you, Dr. Vance.”

He nods, walks away, on to the next patient.

Shane is barely recognizable. Every aspect of his face is swollen and misshapen, including his ears, scrapped raw on the pavement and now tinted with green antiseptic. I’d been expecting to see his poor head swaddled in bandages, but the ICU nurse explains that it’s best to leave the scalp stitches exposed for the time being. The hair has been shaved away around the scalp wound, making it look even more vulnerable.

“He’s breathing on his own,” I observe.

“Mr. Shane is getting oxygen,” the nurse says. “That little tube in his nose.”

“But no respirator.”

“Not unless he needs it.”

“That’s a good sign, no respirator.”

“Very good,” agrees the nurse.

I slip my hand into his, give it a squeeze, hoping for some sort of instinctive response. His hand is cool, dry, and does not respond.

“That doesn’t mean anything one way or the other,” the nurse says, trying to be helpful. “Think of him as being deeply asleep.”

“He’d like that,” I say.

“Excuse me?”

“Never mind. His belongings?”

“In the plastic bag, hanging from the bed.”

Shane’s notes are spattered with blood but legible.

“I’ll give these to the police,” I explain. “It may help.”

Then I kiss his swollen lips and leave.

I’m lying about the police. My son is still out there. I can’t risk being detained. I can’t even wait to see if Randall Shane is going to live, but as I hurry from the hospital I know one thing for sure. He’d understand.

38 already dead

Cutter pulls the stolen Cadillac into a slot behind the boat shed, where it can’t be seen from the access road. Not much traffic in this part of the waterfront, but with his ID out there in the wind, he needs to be ultracautious for the next twelve hours. After that it won’t matter.

Not that he intends to let himself be arrested. When the moment comes, he’ll do a Houdini, or maybe check out permanently, he hasn’t decided. No rush, he’s good at making instant life-or-death decisions under pressure, and right now he has to concentrate on getting the job done. Not for the first time he regrets having to terminate Hinks and Wald, not only because he rather enjoyed their moronic banter, but because it makes the execution of his plan more complicated.

No use crying over split blood, he tells himself. Have to play the hand that’s dealt. Living happily ever after had been, he now realizes, a fantasy, a way to keep focused. The odds of getting away undetected had always been low, on the order of drawing to an inside straight flush. Let it go, Cap, get on with the show.

Next move, prepare the boy.

Inside the shed, Cutter carefully snugs the padlock to the inner hasp. Insuring there will be no surprises from an inquisitive landlord, not that the old man was likely to drop by unannounced. Still, you can’t be too careful.

Turning from the padlocked entrance, he senses that something is wrong. Can’t put his finger on what exactly. A noise or sound? Possibly.

Cutter stops breathing, listens. Notes the transformer hum of the idling air compressor. A barely audible metallic ticking that could be steel drums expanding in the heat—the interior of the shed has gotten quite warm—and from outside the faint cry of a wheeling gull. Nothing out of the ordinary.

He wonders if the contents of the fifty-five-gallon drums are spooking him. Yesterday it seemed vitally important to dispose of the drums and the bodies they contained. Today, much less crucial. It’s just dead meat. Nothing human about it, not anymore. But he’s keenly aware of Hinks and Wald, their telltale hearts beating in the back of his mind. The look in their eyes as they died.

Stop it.

Cutter smacks his palm against his forehead, hard. Grunts and grimaces and forces the kinks out of his mind. The kinks and the hinks and the hinks and the kinks. Stop it. Take a deep breath, hold until your mind clears. Focus on the mission. Focus on saving Jesse, on returning your son to his grieving mother, on making things right in her world, if not your own. You have no life to lose. You’re a dead man, and dead men feel no pain. Dead men do not suffer from guilt or regret. Dead men do as they please.

The boy. Concentrate on the boy in the white room. He’s waiting. He knows what must be done because he saw it in your lying eyes. You think Hinks can haunt you? You ain’t seen nothing yet, amigo. The boy will send your soul to hell like a rocket-propelled grenade, exploding into eternity.

Stop, stop, stop.

Cutter shudders, a full-body writhing, like a snake speed-shedding it’s vile skin. He vomits hot, foul-smelling air. And then he’s clean again and ready for what he must do. Quick-marching to the enclosure, he keys the outer padlock, remembers to lock it behind him. Clever boy, he’ll be plotting an escape. Four strides and he’s at the inner door of the enclosure, noting the blood spatter left by the late Walter Hinks, furious because the clever boy had broken his nose. Hinks complaining, I’m breeving froo my mouf, totally unaware of the comic implications, or that he’d made himself redundant, expendable.

In the white room, chaos.

Cutter instantly notes the missing plywood wall panel, the stink of the upended potty-chair. Sees the ragged hole clawed through the Sheetrock of the outer wall. A hole just big enough for a boy to pass through.

Gone.

The loss brings a banshee howl from his throat. A broken scream of grief, because if the boy is gone, if he’s found a way out of the boat shed, then all the killing was for nothing.

Cutter lets instinct take over. Instinct shaped by years of training. Without even thinking about it, he crashes through the damaged Sheetrock, finds himself standing in the back of the boat shed, with the dilapidated stern of the ancient Chris Craft rising above him.

He searches for a breach in the outer walls. Walls and roof constructed of galvanized steel, fastened from the outside. One of the features that had attracted him to the building in the first place. The boy unscrewed the plywood inner wall somehow—how did he manage that without tools?—but galvanized sheathing is another matter. Needs a drill and a hacksaw, at the very least, or better yet a cutting torch. No torch on the premises, but there’s got to be a hacksaw lying around somewhere. Did he find it? Did clever Tomas cut his way to freedom?

Cutter forces himself to complete a circumnavigation of the outer walls. Smacking on the sheathing as he goes, looking for weak points. With great relief, he ascertains that the outer barrier remains intact, securely fastened to the steel frames of the building.

The boy is inside the shed. Inside and hiding.

“Tomas?” Cutter hardly recognizes his own voice. “It’s Steve. Guess what, you passed the test.”

Making it up as he goes along, as he so often did while interrogating prisoners and suspects and civilian troublemakers. Breaking them with his mind, molding them to his will. Creating stories and scenarios that seemed so plausible that they were soon dying to cooperate.

“This whole thing was a test, Tomas! An elaborate test! We had to know if you were strong enough, clever enough to find a way out of the white room. You passed the test with flying colors. Congratulations!”

Cutter prowls the boat shed, eyes scanning every dark corner, searching for movement, for the quivering of a frightened boy.

“This is part of a top-secret government project, Tomas,” he says, riffing. “You’ve been chosen. We need a boy of your size and your cunning to complete a very important mission. Your mom knows all about it. She gave us her permission.”

Cutter finds the ladder on the floor, under the boat. That’s what his brain noted when he first came into the shed. Not a noise, but a visual clue: the old wooden ladder was missing from the side of the Chris Craft.

He sets the ladder against the hull, climbs up into the cockpit. The engine hatch is open, tools strewn about. All staged, part of making it look good as if the landlord came by to check on progress. Yup, we’re tearing apart that old Chrysler engine, make it purr like an eight-cylinder pussycat.

He crouches. Gets a visual line from the back of the engine compartment into the ruined cabin. Interior panel laminations peeling away, the floor all funky with dry rot. There’s a V-berth forward, a small galley, lazarette lockers under the seats, cupboards and a small enclosed toilet. Plenty of places for a determined eleven-year-old to hide.

Inside the cabin, Cutter sniffs. Amazing how strong and detectable the stink of fear, if you let your brain sort out the various odors. He detects motor oil, rust, mildew, rotting carpet, his own rank odor. Can’t detect the boy, but he must be here. Hiding in a locker, under the V-berth, somewhere very close.

Time to reach out and touch someone.

“Tomas? I’ve got a cell phone in my pocket. Your mother really wants to talk to you. She wants to explain what’s been going on these last few days. I know you won’t believe me—why should you?—but you’ll listen to your mother.”

Using the toe of his boot, Cutter lifts the lid on the lazarette, exposing bundles of rotted rope, rusted anchor chains.

“Come on out, Tomas. You passed the test.”

Cutter moves to the V-berth, all the way forward. He’s about to lift up the ruined cushions and look under the berth when the door to the enclosed toilet creaks open and the boy streaks out.

Clever kid waited until he had a clear shot at the cabin hatchway, must have been clocking him through the keyhole. Doesn’t matter because Cutter is fast and ready and his arms are long. His right hand locks on the boy’s ankle as he tries to scamper up the hatchway.

The boy kicking to no avail.

As Cutter yanks him back inside the cabin, the boy turns, wielding a hacksaw blade in his fist. Cutter doesn’t dare let go of the flailing boy, who is able to rake the saw blade across Cutter’s cheek, laying him open to the bone.

Blood everywhere. Amazing how much flows from a facial wound. Makes things slippery and difficult, but Cutter is a pro and he manages to subdue the struggling boy. Holding him tight, jabbing him with a loaded syringe, hanging on until the powerful anesthetic takes effect and the boy goes limp in his arms.

“Good night, son,” Cutter whispers, and then he allows himself to weep. Weeping for lost boys and sick boys and mothers who yearn for their missing children. Weeping for the already dead and the soon-to-be dead and for a man he used to know.

When the tear ducts finally empty, the dead man gently puts the unconscious boy on the deck and prepares to attend to the wound on his own face. Nothing fancy, just a rudimentary repair that will get him through the next few hours. He sets a shaving mirror on the galley table and lights a wax candle for illumination. Using a sailmaker’s needle and waxed-cotton thread, he stitches himself together. He has in his possession an extensive kit of pharmaceutical drugs, including various anesthetics, but chooses not to numb the wound or dull the pain.

It hurts, and he deserves it.

39 white lady in the moonlight

Back in the day, this was the American dream house. A tidy clapboard Cape-style home with a green patch of lawn and a white picket fence. Friendly neighbors leaning over the fence, trading recipes, resuming conversations that lasted a lifetime. Now the dream is more likely to be a gated community and a million-dollar ski retreat in Vail, and a waterfront condo in South Beach, and enough luxury cars to fill all three garages.

Expectations have changed, but the Cutter family home still looks like a Norman Rockwell postcard. Driving to New London, to an address scrawled in Shane’s hurried hand, I’d been terrified of what I might find. Imagining a dark dungeon where children are tortured, or a crime boss’s fortress, all razor wire and seething menace. The last thing I expected was a cheerful, if somewhat smaller, version of my own home.

Back in our walk-up-apartment days, Ted and I would have killed for a perfect little house like this. Bad choice of words, but my every thought is shaped by morbid anxiety. The rational, analytical part of me knows that my son might well be dead—that’s what kidnappers do, all too often—but if I’m to get through this day, I have to believe that Tommy is alive. That’s the only way I can function, and what gives me the courage to proceed on my own. That, and the feeling, odd as it may seem, that Randall Shane still guides me.

Shane with his head smashed. Shane unconscious, fighting for his own life. And yet somehow he’s along for the ride, long legs folded into the passenger seat, making his little self-deprecating jokes, quietly urging me not to give up hope. What would he think of the white picket fence? Probably remind me that criminals sometimes live in houses just like this. Scratch that rare suburban dad and find a monster. God knows the cable channels are full of them. Moms who drown their children and blame it on a black bogeyman. Dads who set fire to their families to collect enough insurance to buy jewelry for a trophy mistress. We’ve all heard the stories, watched them play out on TV. Getting some sort of vicarious thrill, I suppose, in the certainty that our own lives will never be touched by evil, no matter how familiar the shape it assumes.

But for all that, first impressions count, and I’m almost certain the owner of this house will be another dead end. Stephen Cutter will turn out to be a regular guy, want to know about his old army buddy Big Mike Vernon. He’ll introduce me to his wife and his adopted son and we can commiserate about the sleazy way Family Finders took advantage. But maybe, just maybe, he’ll know something useful, point me in the right direction.

I promise myself that I won’t waste time, that as soon as the Cutters are eliminated as suspects, I’ll move on to the next name on Shane’s list.

The thunderstorm has swept on by for the moment, leaving the black street glistening in the moonlight. Amazing how night rain makes everything look shiny and new. There’s no car in the driveway. Maybe the Cutter family keeps their minivan in the garage, out of the weather. I’ve already decided they drive a car a lot like mine. In any case there are lights on inside, glowing like yellow cat eyes, so I know someone is home. Probably watching TV and munching popcorn. It’s ten o’clock, will their son be in bed by now? Not if he’s anything like Tommy, who has to be herded to his room, no matter how exhausted.

The civilized thing would be to locate their phone number and give them a call, rather than ring the bell at this hour. No time for the social niceties, however. I’m on a mission that won’t end until I’ve cleared every name on Shane’s list.

The gate creaks shut behind me as I move up the walk to the breezeway. Making no effort to be stealthy. Look out, folks, crazy woman on the warpath, come to disturb your peaceful evening.

It occurs to me, approaching the door, that despite the benign look of the place, the Cutters may be paranoid types. New London is not without crime, and home invaders sometimes ring the bell. So there’s always the possibility that Mr. Cutter, a military man, don’t forget, will come to the door armed. Who will he see through the peephole, a desperate woman or a killer mom? A lot depends on whether or not they watch the local news and have an eye for faces.

In this case, I’m hoping that darkness will be my friend.

I’m unable to locate a doorbell button, so I raise my fist and knock. At first there is no responding sound from within. If they’re watching TV, the sound is too low to be detected from the breezeway, so my knock should be audible.

Footsteps. Light footsteps approaching, those of a woman or perhaps a child. I step back and wait for the door to open.

Nothing. I can feel a presence on the other side of the door, but nothing happens, so I knock again, louder.

“Mr. Cutter? Mrs. Cutter? Can I have a word, it’s very important.”

My voice sounds strange and threatening even to me. The footsteps retreat. I pound my fist on the door, rattling the frame. “Please! I just want a word!”

The shadows shift, as if a light somewhere in the house has been switched off. Time to go for broke, let it all out and hope for a connection.

“Mr. Cutter! My name is Kate Bickford, I need your help! Please give me a minute of your time! It’s about my son, my missing son!”

Silence.

Cold anger rises. The Cutters must know by now that I’m not a home invader, not a gang of drug addicts come to rip them off. Probably in there dialing 911, reporting an intruder. And although I’m legally released on bond, I’ve no doubt the cops will want to hold me for questioning in the assault on Randall Shane. I can’t let that happen.

Out of the breezeway I go, around the corner into the backyard. Bang my knee on the leg of a swing set obscured by the shadows. Parts of the backyard bright in the moonlight. Ignoring the thump of pain in my knee, I head for the back windows. Note the curtains tightly drawn, but not so tight as to completely obscure light from what I assume to be the kitchen.

I’m banging my fists against the kitchen window and crying, “Help me! Help me, please! It’s about my son! It’s about my boy!” when a white figure emerges from the ground, a white lady in the moonlight, floating toward me.

A thin, terrified voice asks, “Is this about Jesse? Have you come about Jesse?”

“Mrs. Cutter?”

“You said a boy. A missing boy.”

As the shock of her sudden appearance subsides, I realize that she’s come up out of a basement bulkhead, and that of the two of us, she’s by far the most frightened.

“Can we go inside?” I suggest. “It’s kind of spooky out here.”

Really I’m more concerned about alerting the neighbors, getting called in for disturbing the peace or whatever. And I’m worried that this thin, ethereal wisp of a woman could vanish into the night. A woman who approaches me with great caution, reaching out a slender hand to tentatively touch me, as if to make certain I’m real. Dressed in a thin white robe and fluffy house slippers, she has the glistening brown eyes of a frightened doe.

“Can you keep a secret?” she asks with little-girl shyness.

“I can try.”

“Stephen locks the doors,” she confides in a husky voice that barely carries above a whisper. “He thinks I can’t get out. Promise not to tell?”

“I promise.”

She takes my hand and leads me into the dark basement.

I’m no psychiatrist, but I’ve always assumed there’s a fine line between mental disturbance and full-blown insanity. Equating the former with neurotic behavior or compulsive disorders, and the latter with a disconnection from reality. My impression is that Lyla Cutter lives somewhere in between, in a netherworld where reality comes and goes. The way she keeps studying me, as if waiting for my image to dissolve into hallucination. The nervous things she does with her elegant hands, and a peculiar, affected way she has of clearing her throat. Some of the physical manifestations could be from medication, I suppose, but the important thing is that she’s taken me into her home, into her world—and she wants to talk.

“You came about Jesse,” she says in her whispery voice.

“Not exactly.”

We’re sitting in her living room. Lyla perched on the very edge of a beige divan, so frail she looks like she could be shattered by a loud noise. Her big, nervous eyes imploring me—for what exactly, I can’t quite fathom. She has lovely, waist-length hair. Dark blond streaked with silver, carefully combed—a hundred loving strokes before bed, no doubt. The premature graying is incongruous, because her elfin face is that of a child, unlined and porcelain pale. A woman-child from a nineteenth century melodrama, waiting for Heathcliff to return from the barren moors.

“I’m searching for my son,” I tell her. “Tommy Bickford. He’s been abducted.”

She nods knowingly. “You turn around and they’re gone.”

“Is that what happened to your Jesse?”

She shrugs and makes a vague gesture, as if wafting away invisible smoke. “My beautiful son.”

“I believe your son and mine were both adopted from the same agency,” I tell her. “Family Finders.”

“Stephen would know.”

“Is your husband here, Mrs. Cutter?”

Rather than answer, she leads me to the mantel of a small brick fireplace. “There he is,” she says, indicating a framed photograph of a solidly built but otherwise nondescript man in a military uniform. On closer examination he’s almost but not quite handsome. Could be Bruce, or not, it’s impossible to say. “Stephen was an English teacher, did you know that?” she asks.

“I thought he was a soldier.”

“Before the army he taught at the University of Rhode Island for a year. They let him go, that’s when he decided on an army career like his father. He’d done so well in ROTC, scored off the charts. He’s very, very smart, Stephen. Too smart.”

“Why do you say that?”

“What good does it do, being smart? Thinking he’s oh so clever. He must think I’m stupid, locking all the doors but forgetting about the basement.”

“Yes,” I say, just to be agreeable.

“Thinks I’m stupid about Jesse, too. Telling me lies. That’s what put holes in my brain. Dirty lies. Lies turn into little worms, once they get inside your head. They eat your thoughts.”

“What does your husband lie about, Mrs. Cutter?”

“Oh, just everything,” she responds airily.

“What happened to your son?” I ask. “What happened to Jesse?”

“Shh,” she cautions, holding a pale finger to her lips. “You’ll wake him.”

With that she links her hand in mine and guides me to the stairway. A braided rug on each tread, warm light spilling from the upstairs.

“Your son is here?” I whisper. “Asleep in his room?”

Lyla smiles but does not answer. Her eyes shine with an unbearable, incandescent joy, or madness, or both. Clutching my hand, as if we are little girls about to visit the best dollhouse in the world, she leads me up the stairs and down the hall to her son’s room.

A boy’s room, no question. The posters, toys and carelessly stacked video games could have belonged to my own son. More than that I can’t quite make out, because Lyla doesn’t switch on the light, and the only illumination comes from a wall-socket night-light. A plastic Goofy, glowing in the dark.