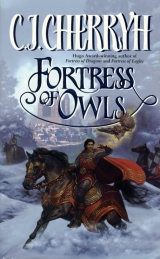

Текст книги "Fortress of Owls"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

Fortress of Owls

C.J. Cherryh

To my editor, Caitlin,

whose belief in this story carried it to print—

To Jane,

who patiently read and remarked, version after version—

And to Beverly,

who compiled the constantly growing lexicon out of all these pages—

Thank you

PROLOGUE

There is magic.

There is wizardry.

There is sorcery.

They are not now, nor were then, the same.

Nine hundred years in the past, in a tower, in a place called Galasien, a prince named Hasufin Heltain had an inordinate fear of death. That fear led him from honest study of wizardry to the darker practice of sorcery.

His teacher in the craft, Mauryl Gestaurien, seeing his student about to outstrip his knowledge in a forbidden direction, brought allies from the fabled north-land, allies whose magic was not taught, but innate. These were the five Sihhë-lords.

In the storm of conflict that followed, not only Hasufin perished, but also ancient Galasien and all its works. Of all that city, only the tower in which Mauryl stood survived.

Ynefel, for so later generations named the tower, became a haunted place, isolated within Marna Wood, its walls holding intact the horrified faces of lost Galasien’s people. The old tower was Mauryl’s point of power, and so he remained bound to it through passing centuries, though he sometimes intervened in the struggles that followed.

The Sihhë took on themselves the task of ruling the southern lands—not the Galasieni, whose fate was bound up with Ynefel, but other newcomers, notably the race of Men, who themselves had crept down from the north. The Sihhë swept across the land, subduing and building, conquering and changing all that the Galasieni had made, creating new authorities and powers to reward their subordinates.

The five true Sihhë lived long, after the nature of their kind, and they left a thin presence of halfling descendants among Men before their passing. The kingdom of Men rapidly spread and populated the lands nearest Ynefel, with that halfling dynasty ruling from the Sihhë hall at unwalled Althalen.

Unchallenged lord of Ynefel’s haunted tower, Mauryl continued in a life by now drawn thin and long, whether by wizardry or by nature: he had now outlasted even the long-lived Sihhë, and watched changes and ominous shifts of power as the blood and the innate Sihhë magic alike ran thinner and thinner in the line of halfling High Kings.

For of all the old powers, Shadows lingered, and haunted certain places in the land. And one of them was Hasufin Heltain.

One day, in the Sihhë capital, within the tributary kingdom of Amefel, in the rule of the halfling Elfwyn Sihhë, a queen gave birth to a stillborn babe. The queen was in mourning—but that mourning gave way to joy when the babe miraculously drew breath and lived, warmed, as she thought, by magic and a mother’s love.

To the queen it was a wonderful gift. But that second life was not the first life. It was not the mother’s innate Sihhë magic, but darkest sorcery that had brought breath into the child—for what lived in the babe was a soul neither Sihhë nor Man: it was Hasufin Heltain, in his second bid for life and power.

Now Hasufin nestled in the heart of the Sihhë aristocracy, still a child, at a time when Mauryl, who might have known him, was shut away in his tower in seclusion, rarely venturing as far as Althalen, for he was finally showing the weakness of the ages Hasufin had not lived.

Other children of the royal house died mysteriously as that fey, ingratiating child grew stronger. Now alarmed, warned by his arts, full of fury and advice, Mauryl came to court to confront the danger. But the queen would not hear a wizard’s warning, far less dispose of a son of the house, her favorite, her dearest and most magical darling, who now and by the deaths of all elder princes was near the throne.

The day that child should attain his majority, and the hour he should rule, Mauryl warned them, the house and the dynasty would perish. But even that plain warning failed to persuade the queen, and the king took his grieving queen’s side, refusing Mauryl’s unthinkable demands to delve into the boy’s nature and destroy their own son.

In desperation and foreseeing ruin, Mauryl turned not to the halfling Sihhë of the court, but to the Men who served them. He conspired with Selwyn Marhanen, the warlord, the Sihhë’s trusted general, and encouraged Selwyn and other Men to bring down the halfling dynasty and take the throne for themselves.

In that fashion Mauryl betrayed the descendants of the very lords he had raised up to prevent Hasufin’s sorcery.

Hence they called Mauryl both Kingmaker, and Kingsbane.

And with the help of Men and with wizards drawn from all across the kingdom, Mauryl seized the chance, insinuating both the Marhanen and his men and a band of wizards into the royal palace. Then Mauryl and his circle held magic at bay while a younger wizard, Emuin, killed the sleeping prince in his chambers—a terrible and bloody deed, and only the first of bloodshed that night.

Destroying Hasufin, however, was the limit of Mauryl’s interest in the matter. The fate of the Sihhë in the hands of Selwyn and his men, even the fate of the wizards who had aided him, was beyond his reach, and Mauryl again retreated to his tower, weary and sick with age. Young Emuin took holy orders, seeking to forget his deed and find some salvation for himself as a Man and a cleric.

Given this opportunity, Selwyn’s own ambition and Men’s fear of magic they did not wield led them to rise in earnest against Sihhë rule: province after province fell to the Marhanen.

The district of Elwynor across the river from Althalen, however, though populated with Men, attempted to remain loyal to the Sihhë-lords, and raised an army to bring against the Marhanen, but dissent and claims and counterclaims of kingship within Elwynor precluded that army from ever taking the field. The Marhanen thus were able to take the entire tributary kingdom of Amefel, in which the capital of Althalen had stood, and treat it as a tributary province.

But rather than rule from Althalen, remote from the heart of his power, and equally claimed by all the lords of Men, Selwyn Marhanen established a capital in the center of his home territory, declared himself king, and by cleverness and ruthlessness set his own allies under his heel, creating them as barons of a new court.

From the new capital at Guelemara, Selwyn dominated all the provinces southward. He and his subjects, mostly Guelenfolk and Ryssandish, were true Men, with no gift for wizardry and no love of it either, leaning rather to priests of the Quinalt and Teranthine sects. Selwyn raised a great shrine next his palace, the Quinaltine, and favored the Quinalt Patriarch, who set a religious seal on all his acts of domination.

Of all Men loyal to the Sihhë, only the Elwynim held their border against the Guelenmen… for that border was on the one hand a broad river, the Lenúalim, and on the other, the haunted precincts of Marna Wood, near the old tower.

So the matter settled… save only the question of Amefel, the province on the Guelen-held side of the Lenúalim River: Selwyn’s hope of holding his lands firm against the Elwynim rested on not allowing an Elwynim presence on that side of the river. So holding Amefel was essential.

Now the history of Amefel was this: Amefel had been an independent kingdom of Men when the first Sihhë-lords walked up to its walls and demanded entry. The kings of Amefel, the Aswyddim, had flung open their gates and helped the Sihhë in their mission to conquer Guelessar, a fact no Guelen and no Guelen king could quite forget. In return for this treachery, the local Aswydd house had enjoyed a unique status under the Sihhë authority, and always styled themselves as kings, as opposed to High Kings, the title the Sihhë reserved for themselves alone.

Having conquered the province, but fearing utter collapse of his uneasily joined kingdom if he became embroiled in a dispute with the Aswydds over their prerogatives, Selwyn Marhanen accorded the Aswydds guarantees of many of their ancient rights, including their religion, and including their titles. So while the Aswydds became vassals of the king of Ylesuin, and were called dukes, they were styled aethelings, that is to say, royal, within their own province of Amefel. This purposely left aside the question of whether the other earls of Amefel bore rank equivalent to the dukes of Guelen and Ryssandisb lands. Since Amefin and Guelenfolk generally avoided appearing in one another’s courts, the question remained tacit and unresolved.

Selwyn thus had Amefel; but the opposing district of Elwynor formed a region almost as large as Ylesuin was with Amefel attached; and its independency from Ylesuin over that first winter had given Elwynor’s lords time to gather forces. By the next spring, with Selwyn in Amefel, the river Lenúalim had become the tacitly unquestioned border. To secure Elwynor as part of Ylesuin remained Selwyn’s unfulfilled dream to his dying day.

The Elwynim meanwhile, having declared a Regency in place of the lost High King at Althalen, were ruled not by a king, but by one of their earls, himself with a glimmering of Sihhë blood, who styled himself Lord Regent. The people of Elwynor took it on stubborn faith that not all the royal house of the Sihhë-lords had perished, that within their lifetimes a new Sihhë-lord, the one they called the King To Come, some surviving prince, would emerge from hiding to overthrow the Marhanen and reestablish the Sihhë kingdom. This time the kingdom would have faithful Elwynor at its heart, and all the loyal subjects would live in peace and Sihhë-blessed prosperity in a new golden age.

The Elwynim, therefore, cherished magic and prized the wizard-gift. But outside the Lord Regent’s line there were far too few who could practice wizardry in any degree. Certainly no one possessed such magic as the Sihhë had used, and there were few enough wizards who would even speak of the King To Come… for the wizards of this age had had firsthand experience of Hasufin Heltain, and they remained aloof from the various lords of the Elwynim who wished to employ them. Those few who had any Sihhë blood whatsoever were likewise reticent, for fear of becoming the center of some rising that could only end in disaster.

So the Elwynim, deserted by their wizards and by those who did carry the blood, became too little wary of magic and those who promised it… and still the years passed into decades without a credible claimant in Elwynor.

Selwyn died. Ylesuin’s rule passed to Selwyn’s son Ináreddrin… and this, after lndreddrin was a middle-aged man with two previous marriages and two grown sons.

Now Ináreddrin was Guelen to the core, which meant devoutly, blindly Quinalt—his mother’s influence. As prince, he had no love of his uncivil warlord father, but a great deal of fear of him. He grew up with no tolerance for other faiths, despite the exigencies of the Amefin treaty. He lost patience with his wild eldest son, Cefwyn, for Cefwyn took his grandfather’s example and clung to the Teranthine tutor, Emuin (that same Emuin who had aided Mauryl at Althalen), whom Selwyn had appointed royal tutor for his grandsons.

This was no accident: Selwyn as a reigning king had found priests and the Quinalt a convenient resource, and to that end he had supported them—they kept the Guelenfolk obedient. But to safeguard his kingdom for the years to come, and with at least some fear of what he had faced at Althalen, Selwyn had wanted his grandsons never to dread priests or wizards—rather to understand them, and to have one of the best on their side.

This was a source of bitter argument within the royal house: the queen died, Ináreddrin grew more alienated from his father, and the very year Selwyn died and lndreddrin became king, Ináreddrin persuaded his younger son Efanor into the strictest Quinalt faith—lavishing on him all the affection he denied the elder son.

So did the highest barons, notably of the provinces of Ryssand and Murandys, favor Efanor, and there was talk of overturning the succession—for the more Efanor became religious, the more Cefwyn, the crown prince and heir, consoled himself with wild escapades, sorties on the border, and women… very many women.

Still, by Guelen law and custom, even by the tenets of the Quinalt itself, Cefwyn was, incontrovertibly, the heir.

So Ináreddrin, either in hopes that administrative responsibility would temper Cefwyn—or, it was whispered, in hopes some assassin or border skirmish would make Efanor his heir—sent Cefwyn to administer the Amefin garrison with the courtesy title of viceroy, thus keeping a firmer Marhanen hand on that curiously independent province.

Now, ordinarily and by the treaty, there was no such thing as a viceroy in Amefel, and the duke of Amefel, Heryn Aswydd, was not at all pleased by this gesture… but Heryn kept his discontent to himself, even agreeing to report to Ináreddrin regarding the prince’s behavior, and on the worsening situation across the river—for there was a reason Ináreddrin had felt a need for a firmer Guelen presence in Amefel. The Regent in Elwynor had no children but a daughter of his old age. The lords of Elwynor, weary of waiting for the appearance of a High King, were now saying the Regent should choose one of them to be king, as he was advanced in years… and the only way for one earl to gain any legitimate connection with royalty was by marrying the Lord Regent’s daughter.

The Regent, Uleman Syrillas, refused all offers, swearing that his only child, his daughter– Ninévrisë, would wield the power of Regent herself… unprecedented, among the Elwynim and the Sihhë kings, that a woman should rule in her own right. But Uleman had prepared his daughter to rule… and when the day came that a suitor tried to enforce his demands with arms and carry Ninévrisë away, the Regent refused to bow.

Elwynor sank into civil war… and that war insinuated itself across the river into Amefel: there were families with kin on both sides of the river.

So it was into this situation that Ináreddrin sent Prince Cefwyn to strengthen the garrison.

And it was entirely characteristic of Ináreddrin that he told Heryn he was to watch Cefwyn and told Cefwyn to watch Heryn, who was, after all, a heretic Bryaltine.

Unbeknownst to the king, in fact, Duke Heryn was in league with one of the rebel earls in Elwynor.

Others of the Elwynim rebels, those who lacked force of arms, were keen to have wizardly sanction.

And Hasufin Heltain, once again dead, as Men knew death, was waiting only for such a moment of crisis and a condition in the stars. Through the situation in Elwynor, that ancient spirit found his way closer and closer to life.

Mauryl, however, had foreseen the hour, and had saved his strength for one grand, unprecedented spell, a Summoning and a Shaping, a revenant brought forth from the fire of Mauryl’s hearth—not a perfect effort, however, nor mature nor threatening. To Mauryl’s distress the young man thus Summoned lacked all memory of what or who he had been.

Mauryl called his Summoning… Tristen. And the day Mauryl lost his struggle with Hasufin, Tristen, a young man with the innocence of the newly born, set forth into the world, hoping to do the things Mauryl intended.

The Road which began from Ynefel led Tristen not to a wizard, who would teach him, as Tristen had hoped, but straight to Prince Cefwyn, on a night when, despising his host, Heryn Aswydd, Cefwyn was sleeping with Heryn’s twin sisters, Orien and Tarien.

Tristen was as innocent a soul as ever Cefwyn had met… incapable of anger, feckless, and utterly outspoken, but wizardous at the very least. When Tristen confessed he was Mauryl’s, Cefwyn’s curiosity was immediately engaged; and when Cefwyn began to deal with Tristen, he found himself snared indeed—for after his grandfather’s anger and his father’s cold dislike of him, after the northern lords’ wish for Efanor and his own brother’s desertion, this was the only wholehearted offer of a stranger’s friendship he had ever met.

Meanwhile Tristen continued to learn… for he was a blank slate on which Mauryl’s spell was still writing, Unfolding new things in wizardous fashion, at need, and providing him knowledge unpredictable in its scope and its deficiency. Tristen wondered at butterflies… and asked questions that shot straight to the prince’s heart.

Cefwyn’s affection toward this wizardous stranger made Duke Heryn Aswydd hasten his plans… for Cefwyn was growing fey and difficult. Heryn used King Ináreddrin’s suspicion of his son to lure the king and Prince Efanor to Amefel… hoping then to do away with Cefwyn and the younger prince in the same stroke as the king, and thus overthrow the Marhanen dynasty.

Prince Efanor, however, had not ridden with the king; he had ridden straight to Cefwyn to accuse and berate his brother, determined to find out the truth ahead of their father’s arrival, to spring any trap upon himself if one existed. It was a brave act. And when Cefwyn knew his father had listened to Lord Heryn, he was horrified, and rode at once to prevent the ambush, no matter the danger.

He arrived too late, and was almost overwhelmed by the force that had killed the king; but the knowledge of warfare Unfolded to Tristen that day, on that battlefield, and the gentle stranger turned warrior. He rescued the princes, defeated Heryn’s allies—and when Cefwyn reached Henas’amef not only unexpectedly alive, but king of Ylesuin, Heryn paid with his life for his treason.

Tristen, however, strayed into the hills, where he fell in with the Lord Regent of Elwynor, who was dying, in hiding from the same enemies as had killed his old enemy lndreddrin. The old Regent’s last wish was to bring his daughter Ninévrisë to Cefwyn Marhanen—as his bride… for the only hope for the Regency now was peace with Ylesuin.

So Tristen brought Lady Ninévrisë to Cefwyn, and Cefwyn Marhanen, new king of Ylesuin, fell headlong in love with the new Regent of Elwynor.

Tristen, for his services, became a lord of Ylesuin, no longer mocked for his simplicity, but now feared, for no one who had seen him fight could discount him. And Heryn’s sister Orien became duchess of Amefel, since Cefwyn was not ready to set aside the entire dynasty, and had seen none but ordinary flaws in Orien. Orien, however, was bent on revenge and lied in her oaths. Lacking armies, lacking skill in war, she sought another means to power… and became prey to sorcerous whispers from the enemy, Hasufin Heltain.

Hasufin’s immediate goal was an entry into the fortress of Henas’amef, but because of Tristen and Emuin, he could not breach the wards: so he moved his pawn Orien to make an attempt on Cefwyn’s life, moved another pawn to attempt Emuin’s life, and at the same time drew the rebel army across the river in all-out war.

–

The first two failed. The third was aimed at Tristen, whom Hasufin recognized as Mauryl’s last and most effective weapon. Sorcery would be at its strongest in a moment of chance and upheaval, and there was no moment of upheaval greater than the shifting tides of a battlefield: thus Hasufin made his strongest bid to break into the world and destroy Tristen, who stood between him and life and substance.

In the world of Men, at a place called Lewenbrook, near Ynefel, the Elwynim rebels, under Lord Aseyneddin, met Cefwyn Marhanen’s opposing army. That was the conflict Men fought.

But when Aseyneddin faltered, Hasufin sent out tides of sorcery in reckless disregard. A wall of Shadow rolled down on the field, and those it touched it took and did not give up. It was Hasufin’s manifestation, and all aimed at Tristen’s destruction.

Tristen, however, took up magic as he took up his weapons, when the challenge came. When Hasufin Heltain loosed his sorcery, Tristen rode into the Shadow, penetrated into Ynefel itself, and drove Hasufin from his unsteady Place in the world.

Cefwyn meanwhile had prevailed in the unnatural darkness, and when the sun broke free of the Shadow, he had held his army together. Aseyneddin’s forces, such as survived, shattered and ran in panic.

It was a long way back to the world, however, from where Tristen had gone. Exhausted, hurt, at the end of his purpose, Tristen resigned his wizard-made life, finished with Mauryl’s purpose, too weary to wake to the world of Men.

But he had once given his shieldman Uwen, an ordinary Man with not a shred of magic in him, the power to call his name. This Uwen did, the devotion of a simple man seeking his lost lord on the battlefield, and Tristen came.

–

There was a moment, then, when Cefwyn stood victorious over the rebels, that he might have launched forward into Elwynor: the southern lords had rallied to the new king, and would have followed him. But Cefwyn saw his army badly battered and in need of regrouping, he knew the enemy was on the run, meaning they would sink invisibly into Elwynor, and he knew, as a new king, he had left matters uncertain behind him. The majority of his kingdom did not even know they had changed one king for another, and the treaty he had made with Ninévrisë had never reached his people.

It was the end of summer. Good campaigning weather still remained, but harsh northern winters could make fighting impossible. So for good or for ill, Cefwyn opted not to plunge his exhausted army, lacking maps or any sort of preparation, into the unknown situation inside Elwynor, which had been several years in anarchy and still had rival claimants to the Regency. Instead he chose to regroup, settle his domestic affairs, marry the lady Regent, ratify the marriage treaty, and rally the rest of his kingdom behind him in a campaign to begin in the spring.

He went home, trusting his father’s trusted men, gathering up his brother Efanor, and attempting simply to take up the power of the monarchy as it had been. But when he reached his capital, he discovered his father’s closest friends among the barons meant to wrest the power into their own hands… as his father had let them do much as they pleased for years. It was no longer a matter of the northernmost barons preferring Efanor. They had had a king they could rule, they meant to have another one, and in their minds Cefwyn was a wastrel prince who would be a weak king: he could be managed, they had said among themselves, if they kept him diverted.

That was not, however, the king who came home to them: Cefwyn arrived surrounded by their southern rivals, who were clearly in favor, and allied to Mauryl’s heir, betrothed to the Elwynim Regent, and proposing war on the Elwynim rebels. This was not Ináreddrin’s dissolute son: it was Selwyn’s hard-handed grandson, and the barons were appalled.

So they took a new tactic… they were older, cannier, more experienced in court politics. They would use the priests, prevent the marriage, treat the lady Regent as a captive—and seize land in Elwynor.

Cefwyn was as determined to bring them into line and shake the kingdom into order. He sent the southern barons home to attend their harvests and prepare for war, all but Cevulirn, whose horsemen had less reliance on such seasons and who stayed as a shadowy observer for southern interests.

In Elwynor, meanwhile, another of the rebel lords, the survivor of all the others, took advantage of the confusion to bring his army out of the hills, besiege his own capital of Ilefínian, and declare the lady Regent captive in the hands of the Marhanen king.

Cefwyn took measures to ensure that the Quinalt would approve the marriage and the treaty by which he would agree to put Elwynor in the hands of as lady Regent, independent of the Crown ofYlesuin.

The barons retaliated with an attempt to limit the monarchy over them.

And if Tristen had been feared in the south, he found he was abhorred in the north. He kept to the shadows… for Cefwyn, fighting for his right to wed the woman he loved and trying to wrest back sovereignty in his own capital, feared Tristen’s being caught up in the fight.

Obscurity, however, only increased the mystery. The barons saw Tristen as an influence on Cefwyn that must be eliminated. On a night when lightning, whether by chance or wizardry, struck the Quinalt roof, a penny in the offering in the Quinaltine was found to be Sihhë coinage, with forbidden symbols on it; and the charge was forbidden wizardry, attacking the Quinalt and the gods.

Cefwyn suspected that His Holiness the Patriarch was devious enough to substitute the damning coin, and Cefwyn moved quickly to force the Patriarch into his camp. But the coin together with the lightning threw the wider court into such alarm that Cefwyn felt compelled to remove Tristen from controversy. In what he thought a clever and protective stroke, he sent Tristen back to Amefel not as a refugee in disgrace, but as duke ofAmefel… a replacement for the viceroy he had left in charge.

Now this viceroy was Parsynan, appointed on the advice of some of these same troublesome barons, notably Murandys and Ryssand… for Cefwyn had exiled Orien Aswydd and her sister to a Teranthine nunnery for their betrayal, and had never appointed another duke, until now.

Hearing that Tristen was going to Amefel, and that Parsynan was recalled, Corswyndam Lord Ryssand panicked, fearing that certain records might fall into the king’s hands. So he sent a rider to advise Parsynan of his imminent replacement.

Corswyndam’s courier rode hard enough to reach the town of Henas’amef the Amefin capital, ahead of the royal messenger bearing the official notice. Parsynan quite naïvely brought his local ally Lord Cuthan, an Aswydd by remote kinship, into his confidence, since this man had supported him against his brother earls before.

Cuthan, however, was in on a plot by the Elwynim to create war in Amefel, a distraction for Cefwyn, and the plan was to seize the citadel, on the promise Elwynim troops would then invade and engage with the king’s

–

forces. Cuthan not only failed to warn Parsynan it was coming… but he also said nothing to warn his brother lords that a detachment of the king’s forces was about to arrive. One or the other would happen first, and Cuthan meant to stay safe.

So, ignorant of important pieces of information, certain Amefin lords, led by Earl Edwyll of Meiden, seized the South Court of the fortress of Amefel to wait for Elwynim support.

In the same hour, losing courage, Cuthan told the other earls the king’s forces were coming, and there were as yet no Elwynim.

The other earls failed to join Edwyll… which suited Cuthan: he and Edwyll were old rivals, and now Edwyll was guilty of treason, sitting in the fortress with the king’s forces approaching. And none of the rest of them were guilty of anything.

In a thunderstroke, before anyone had thought, Tristen arrived and, to the cheers of the populace, moved swiftly uphill to the fortress to take possession. The earls of Amefel rapidly set themselves on the winning side.

Edwyll, meanwhile, died, having enjoyed a cup of wine out of Orien Aswydd’s cups, untouched since the place was sealed at her exile… and whether Edwyll’s death was latent wizardry attached to Orien’s property, or simple bad luck, the command of the rebels now devolved to Edwyll’s son, thane Crissand, who was forced to surrender. Tristen now had the fortress in his hands.

Not satisfied with the death of Earl Edwyll, however, Parsynan, in command of the garrison troops, seized the prisoners from Tristen’s officers and began executing them.

Tristen found out in time to save Crissand… and dismissed Lord Parsynan from the town in the middle of the night and without his possessions, scandalous treatment of a noble king’s officer, but if there was anything wanting to make Tristen the hero of Henas’amef, this settled matters: the people were delighted, wildly cheering their new lord. Crissand, Edwyll’s son, himself of remote Aswydd lineage, swore fealty to Tristen in such absolute terms it offended the Guelen clerks who had come with Tristen, for Crissand owned Tristen as his overlord after the Aswydd kind, aetheling, a royal lord, reopening all the old controversy about the status of Amefel as a sovereign kingdom. Crissand had become Tristen’s friend and most fervent ally among the earls of Amefel… who, given a lord they respected, came rapidly into line, united for the first time in decades.

In the succeeding hours Tristen gained both the burned remnant of Mauryl’s letters, and Lord Ryssand’s letter to Parsynan. The first told him that correspondence Mauryl had had with the lords of Amefel might have some modern relevancy… one archivist had murdered the other and run with the letters. The second letter revealed Corswyndam’s connivance with Parsynan.

Tristen sent Ryssand’s letter posthaste to Guelessar, while Cuthan, revealed for a traitor to both sides, took advantage of Tristen’s leniency to flee to Elwynor.

In the capital, Ryssand knew he had to move quickly to lessen the king’s power against any baron, and one of his clerks had reported that the office of Regent of Elwynor, which Ninévrisë claimed, included priestly functions. So at Ryssand’s instigation, the Holy Quinalt rose up in protest of a woman in priestly rites, which would break the marriage treaty.

Cefwyn countered with another compromise and a trade of favors with the Holy Father: Ninévrisë agreed to state that she was and had always been of the Bryaltine sect, that recognized though scantly respectable Amefin religion, and if she agreed to accept a priest of that faith as her priest, leaving aside other difficult questions, the Quinalt would perform the wedding.

The barons now came with the last and worst: charges of infidelity, ’s with Tristen, laughable if one knew them… but Ryssand’s daughter Artisane was prepared to perjure herself to bring Ninévrisë down, and Ryssand’s son Brugan brought the charges to Cefwyn, along with a document giving much of his power to the barons, which was clearly the alternative.

Therein Ryssand overstepped himself: it gave an excuse for a loyal baron, Cevulirn oflvanor, to challenge Brugan and, by killing him, change the character of the effort. The gods had let a man of the king’s kill the man who made the charge, and if Ryssand should make public the attack on , that fact would come out.