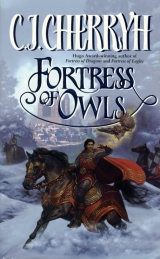

Текст книги "Fortress of Owls"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

“Fools,” Uwen said, tugging his hand into a gauntlet.

Uwen should be here, administering the town. But Uwen would not let him ride out alone, and on the other hand, Amefel was too volatile a command, the feeling against Guelenfolk far too bitter to leave Captain Anwyll in charge of the capital. He left command to Lord Drumman, whom he trusted, an Amefin, and he hoped the Guelen Guard would create no new difficulty about it… not mentioning the other earls. He was only now learning which earl resented which other one in what particular respect.

But Drumman was generally liked. Therefore, he sent Anwyll to do the one thing a determined Guelenman might do with the goodwill of the earls: guard the river; Uwen he set in as much authority as Uwen was willing to take, but today Uwen went with him… his guard did, too, Guelen and conspicuously fair amid the generally darker Amefin.

“There’s Lord Meiden, m’lord,” Lusin said, and indeed, a little late himself, Earl Crissand had just ridden under the gate and past the rear of the inbound carts.

But not just the earl. The earl brought with him his own escort, the men of Meiden all cloaked and armed, and now completely obstructing the small courtyard around the oxcarts… indeed, Crissand’s guard turned out to exceed his own, a show of force from a decimated house… he did not fail to notice it himself, as all around him the men of his own, Guelen-born, escort stiffened their backs and stared with misgivings.

Crissand, too, seemed to realize he had made a misstep, and rode up much more meekly than he had ridden in. “My lord,” Crissand said, above the discontent lowing of oxen, and dismounted to pay his respects. “I had expected far more men. Forgive me. Shall I send back my guard?”

Did Crissand think so many guards prudent, and was Crissand right in estimating safety and risk out in his own rural land?

Crissand was young as he, at least in apparent years, and did many things to excess, but he had never seemed to be a fool regarding Amefel, and knew his land. They were Crissand’s villages they proposed to visit. Tristen’s eyes passed worriedly over the situation, as confusion reigned for a moment in the small yard and the Guelenmen of the Dragon Guard eyed the Amefin of Crissand’s household in suspicious assessment amid the oxcarts.

In the same moment a stableboy oblivious to all the rivalry of Guelen and Amefin escorts brought red Gery up, holding out the reins. Tristen found it easier to set his foot in the stirrup and be under way than to sort out the excess of guards and weapons and precedences and this lord’s sensibilities and that lord’s distrust. He was not unarmed, standing naked in his bath. He did not fear Crissand.

“Bring them,” he said to Crissand’s anxious looking up at him.

In truth he would be solely an Amefin lord, relying only on these men, once he dismissed his Guelen forces back to Guelessar, as he must when he had raised sufficient Amefin units. Was that why Crissand had brought so many—that Crissand had proposed to supply the escort for him?

How he would have a ducal regiment in any good order by spring without setting one earl against another was another question—which earldom would contribute men and how many? But it was not today’s question… for once he was up and had Gery’s lively force under him, the motion and the prospect of freedom chased all more complex thoughts from his head. He was in the right place; he had done the right things. He ached from too much sitting in chairs and far too many difficult and contentious decisions in recent days. He knew he had sat blind to the land he was supposed to be governing, and hearing his choices only from the lips of advisers. Now he had that saddle under him and Gery willing and eager to move, he was eager to go, and circled Gery about with an eye to the gate as Uwen and his guard mounted up. The two troops muddled ranks for a moment, then began to sort out in fair good spirits.

The Dragon Guard themselves had been glad to have an outing away from the barracks, and good humor prevailed, though Tristen suspected a sharp rivalry still manifested in the haste and smartness with which the banner of Amefel unfurled in Sergeant Gedd’s hands. The Eagle on its red field made a brave splash of color against the whites and browns and grays of the yard; and after it the two black banners of his other honors unrolled from their staffs, the Tower of the Lord Warden of Ynefel and the Tower and Star of the Lord Marshal of Althalen… both honors without inhabitants, but Amefin ones, so the Amefin made much of them. It was a brave show; and protocol held the banner of the Earl of Meiden to unfurl second: a blue banner with the Sun in gold, as brave and bright as Earl Crissand himself, dark as his fellow Amefin but with a glance like the summer sky. He might have been embarrassed for a moment in the relative size of their guards; but the day was so brisk and keen there was no resisting the natural joy in him. There was love in Crissand Adiran, of all the earls, a disposition to be near him, to seek his friendship—and how could he have thought ill of Crissand’s reasons?

There was love, a reliable and a real love grown in a handful of days, and Tristen did not know why it was: friendship had happened to both of them, on the sudden, completely aside from Tristen’s both endangering and saving Crissand’s life. It was no reason related to that, it was no reason that either of them quite knew. Crissand had simply risen on his horizon like the sun of his banner… and that was that. Prudence aside, putting by all worry for master Emuin and his advice, and for the workmen and for all the household, all in the friendship that had begun to exist, they were together, and there was a great deal right with the day simply in that.

With banners in the lead they rode out the iron-barred gates of the Zeide, gate-guards standing to sharp attention to salute them. The racket of their hooves echoed off the high frontages of the great houses around about as, wasting no time in the square, they began the downward course… numerous enough for an armed venture rather than a ride for pleasure, and they drew curious stares from those with business about the fortress gates, but as they entered the street the sun broke from a moment of cloud, shining all the way down the high street to midtown, lighting a blinding white blanket on gables of the high frontages, and that glorious sight gave no room for worry.

Traffic had worn off the snow in the streets to a little edge of soiled ice, and the brown cobbles ran with disappointingly ugly melt down that trace of sunlight, but above, about the eaves, all was glorious. The houses grown familiar to Tristen’s eye from the summer were all frosted with snow and hung with icicles, and the sunlight danced and shone on them as they rode, shutters dislodging small falls of snow and breakage of ice as they opened for townsmen to see. The cheer in the company spread to the onlookers, who waved happily at this first sight of their new lord outside the fortress walls, and in company with Amefin. Already they had encouraged high spirits.

And, oh, the icicles… small ones, large ones, and a prodigious great one at the gable of the baker’s shop, on a street as familiar to Tristen’s sight as his own hallway atop the hill… familiar, yet he had never noticed that gable, never noticed half the nooks and crannies and overhangs of the high buildings that carried such sun-touched jewelry today.

It seemed wondrous to him, even here in the close streets. He turned to look behind them, gazing past the ranks of ill-assorted guardsmen and cheering townsfolk as dogs yapped and gave chase. It gave him the unexpected view of the high walls and iron gates of the Zeide, all jeweled and shining as if enchantment had touched them.

Lord Sihhë! someone shouted out then, at which he glanced forward in dismay. Others called it out from the windows, Lord Sihhë and Meiden! in high good cheer. The sound racketed through the town, and people shouted it from the street.

Lord Sihhë indeed. That, he had not wished. The Holy Father in Guelessar would never approve that title the people gave him; and the local Quinalt patriarch, before whom he had to maintain a good appearance, was sure to get the rumor of what the people shouted. Feckless as he had been, he had learned the price words cost, and he wished he could hush those particular cries… but they did it of love, nothing ill meant, and it was all up and down the street. The old blood might be anathema to the Guelen Quinalt; but among Amefin folk, who were Bryaltines, it was honor they paid him. They shouted it in delight: Lord Sihhë and Meiden! as Crissand waved happily at the onlookers, the partnership of the oldest of Amefin houses with the banner of Althalen, as it had been a hundred years ago, when Meiden was the friend of the Sihhë… was it that they thought of?

Past the crossing at midtown, they gathered speed on the relatively clear cobbles and jogged briskly downhill past a last few side streets and the last few shops and trades, down to the rougher, more temporary buildings near the walls. The town’s lower gates stood open: they ordinarily did so by broad daylight; and consequently there was no delay at all to their riding out, no more concern for townsfolk and titles or the determined town dogs. The wide snowy expanse beyond the dark stone arch was freedom for a day.

He found himself lord of a changed land as he rode out… white, white, where the brown of autumn had been, and before that, the green and gold of enchanted summer… all gone, all buried and blanketed and tucked away for the winter.

All the knotty questions of armies and rivalries and titles and entitlements of lords fell away in broad, bright wonder, for if breath-blurred windows had shown him the surrounding fields and orchards as hazy white, the utter expanse of it had until now escaped him. There just was no cease of it. Boundaries that all summer and fall had said here is one field and here another, here a meadow, there a field… all were overlain until stone fences and sheep-hedges made no more than ridges.

But while those grand lines had blurred, he had never, at the distance of his windows, imagined the wealth of details written in the new snow, the record of farmers’ traffic that told where men and beasts had walked hours, even days ago. The landing of a bird left traces, like marks on parchment.

Shadows of birds, too, passed on the snow, prompting him to look up, and then to smile, for his birds flew above them, outward bound, his silly, beloved pigeons, faring out on their business, as by evening they would fly home to the towers and ledges of the fortress, looking for bread and their perches. They circled over once, and flew out ahead, seeming to have urgent business in mind… a barn, perhaps the spill of a granary door: the woods never suited them. The woods were Owl’s domain.

“Are they the ones from the tower?” Crissand asked, himself looking up.

“I think they are.”

“Do they follow you?” Crissand asked.

“They go where they like. I don’t govern them.”

Did his birds fly sometimes far afield, and did they sometimes meet the pigeons that nested at Ynefel?

He was not sure, indeed, that anything lived at Ynefel. He saw them sweep a turn toward the west, indeed, away, away toward the river… and equally toward the stony hills around ruined Althalen. Ruins suited them well: they liked ledges and stonework. Certainly birds that dared nest at Ynefel, if they were the same birds, would never fear Althalen.

“Nothing of omen,” Crissand wondered in some anxiousness.

“No,” he said as they rode, “only birds.”

A cloud came, passed. Many clouds came and went, and fields blazed white after shadow. Snow on bare gray apple branches made lacework of the eastern view. Moving shadows grayed the hills, and the sky was an amazing clear blue with fat wandering clouds, while the morning’s fall cast a winter glamour on common stones and roadside broom. The horses’ nostrils flared wide, their ears pricked forward in the bracing air. Their steps were willingly quick and light.

“Is it the South Road we use all the way?” he asked Crissand at a certain point. He had looked at maps; but the hills were a maze of small trails, some missing from the charts, he much suspected, and he was very willing to use a shortcut and go up into the wonderful hills if Crissand knew one.

“Yes, my lord, south an hour,” Crissand said, “to Padys Spring. There’s an old shrine, and the village track to Levey comes in there, only over the ridge. We’ll leave the main road there.”

Padys rang not at all off memory, neither the village of Levey, nor Padys Spring… though he was sure there should be water where Crissand described a spring being.

But, also, to his vague thought, the name of the place was not quite Padys.

“Bathurys,” he said suddenly, pleased to have caught it.

“M’lord?”

“Bathurys,” he said. It seemed increasingly sure to him that that was the proper name of the spring, as sometimes the very old names came to him. There was a shrine, Crissand had already said; but he was less sure of that fact.

But there at least should be a spring at a place called Bathurys, and when he set a right name to it, he far better recalled the lay of the land… thought of a village of gray stone, and flocks of sheep.

It was not so far a ride, then. He felt happy both in Gery’s free and cheerful movement and in the increasing good temper of the company around him. He even heard laughter among the soldiers behind, and beside him, Uwen, who habitually was shy of lords’ company, was not shy in Crissand’s presence, and bantered somewhat with Crissand’s captain, riding near them.

The two guard companies, the Dragons and the men of Meiden, had fought each other with bloody determination the night of his arrival; but the Dragons had also rescued Crissand and his men from execution, so with this particular Guelen regiment, the tally sheet of good and bad was mixed. Besides, the Dragons were a Guelen company the Amefin held in higher regard than they had ever held for the Guelen Guard, even before Parsynan’s rule here: the Dragons, better disciplined, had never been hard-handed with the townsfolk, never stolen, never done any of the things the Guelens had done, so he had it reported. So, warily, cautiously, goodwill grew, in the amity of the officers and the lords, so in the ranks.

And, truth, by the time they had passed the first rest and ridden over the icy bridge, Uwen and the captain of Meiden’s house guard were cheerfully comparing winters they had known, and arguing about the merits of sheep, while the men in the ranks had proceeded to local autumn, local ale, the taverns in Guelemara and those in Amefel, and the women they knew.

The men found their ways of talking. But Tristen labored in his converse with Crissand as if they were strangers, for all their prior dealings had been policy and statecraft. Now they talked idly, as common men did, about the autumn, the land, the flocks, and the apples. Uwen, who had been a farmer before he was a soldier, knew far more about any of these things, Tristen was sure, but Crissand knew everything there was to know about apples, their type, and their value. All Tristen found to do was ask question and question and question. Crissand did know his people’s trade, down to the tending of apple orchards and sheep, which he had done with his own hands, and had no hesitation in the answers. “The flocks are most of my people’s living,” Crissand said, “more so than the orchards in the last five years, since the blight. Lord Drumman’s district is all orchards of one kind and another. So is Azant’s. But we fared well enough in Meiden, since we have both sheep and apples: the barley never does well, to speak of: that comes from the east and from Imor and Llymaryn.”

And again, after a time, Crissand said, “Lewenbrook was hardest on Levey of all Meiden’s villages. Fourteen dead is a heavy toll for a village of two hundred, six more wounded, seven lost with my guard, a fortnight gone. That’s a quarter of all the village, and every man they had between sixteen and thirty.”

Tristen had not reckoned the dead in those terms, but it came clear to him, such a hardship.

“A great many widows for a small village,” Crissand said, “and them to do the spring plowing, except I gift younger sons from some of my other villages to go and plant for the widows when they’ve seen to their own fields.”

“We will not have Amefel for a battlefield again,” Tristen vowed, with all knowledge Cefwyn was going to war and that he must. He would not have the war cross the river. He was resolved on that.

“Gods grant,” Crissand said fervently.

Sun flashed about them when Crissand said it. It had been a moment of cloud, which passed… and indeed now there was certainly no tardiness in the heavens, though the wind was still. Spots of sunlight came and went with increasing rapidity across the land, glorious patches of light and gray shadow on the snow.

The talk was, albeit puzzling to him, also enlightening, even in this first part of their ride, of the things Crissand and the other lords had suffered, and what the villages needed. They had a certain shyness of each other at the first, and Crissand seemed to worry about offending him, telling the truth as Crissand would, but everything Crissand said, he heard. From orchards and sheep they talked on about this and that, gossiped about various of the lords, but none unkindly: Drumman’s ambition for a new breed of sheep, Azant’s daughter’s two marriages, her widowed at Lewenbrook, only seven days a bride—but not the only tragedy. Parsynan, so he had no difficulty understanding at all, had done nothing to mend the situation in the villages, nothing to recover Emwy from its destruction, nothing to help Edwyll’s heavy losses, only to collect taxes for the coronation levy and further punish the villages that had helped win the day.

“Then the king’s men came counting granaries and sheep again,” Crissand said, “and that was the thing that pushed my father toward rebellion, my lord. We’ve no villages starving yet, but by next year they’d be eating the seed corn, and that, that, my lord, there’s no recovering. So the Elwynim offer tempted my father, and the king’s men made him angry. That’s the truth of it. I don’t excuse our actions, but I report the reason of them.”

“I’ve yet to understand all Parsynan’s reasons,” Tristen said, “but at least by what I’ve seen, he built nothing. And I want the repairs made and no great amount spent, and no gold ornaments, and none of this. Yet they want to carve the doors, which is a great deal of expense, and more time, yet everyone, even the servants, say I should do it… while the villages want food. Is that good sense?”

“Our duke shouldn’t have plain doors,” Crissand said, “and if he understands the plight of the villages and sees to it they have grain, there’s no man will complain about the duke’s doors.”

“I need troops to the riverside more,” Tristen said in a low voice, still discontent with the delays for wood-carving, more and more convinced he should never have been persuaded to agree to it at all. “Any door would do to shut out the cold. I need canvas, I need bows, and I need horses and food.”

“To attack Elwynor, my lord?”

“To keep the war out of Amefel. And the armory. There’s another difficulty. Parsynan did nothing to maintain it; Lord Heryn kept it badly; Cefwyn set it to rights, and when the master armorer left to go with the king, Parsynan set no one in charge of it, and there’s no agreement between the tally and what’s there. I brought a good man back with me, Cossun, master Peygan’s assistant, and he can’t find records there or in the archive.”

“I fear there was theft,” Crissand said. “I even fear my men did some of it. But those weapons we have…” Crissand did not look at him when he added, “… even today. But Meiden wasn’t the only one to take weapons. The garrison made free of it, if my lord wants the truth. The Guelen Guard.”

“Yet where are the weapons?”

“Sold in the town, and pledged for drink, and such, in the taverns. The weapons are there, my lord, just not in the armory. Except if there was gold or silver, and that might have gone gods know where. To the purveyors of wine and ale and food, not to mention other things.”

It was a revelation. So were many things, in this fortnight of his rule here. Everywhere he looked there was another manifestation of Parsynan’s flagrant misrule, another particular in which a self-serving man had stripped the town and the garrison of whatever value might have served the people of Amefel. The Guelens, lax in discipline under Parsynan’s rule, had seemed to view the Amefin armory as a place from which to take what they would—and knowing what he knew, yes, he could believe no officer had prevented it.

“Did you hear that, Uwen?”

“Aye,” Uwen said, soberly. “An’ I ain’t surprised if those weapons is scattered through town, an’ I ain’t surprised if a lot of legs has helped ’em walk there, not just the Guelens. Metal’s metal, m’lord, an’ a good blade for a tanner or a wheelwright, that ain’t unlikely at all. Is it?” Uwen asked of the Meiden captain.

The man agreed. “I wouldn’t be surprised.”

“And the archive?” Tristen asked Crissand.

“A man who wanted to remove a deed or change one,” Crissand said, “could do that, for gold. That was always true. Which is as good as stealing, but in one case it was done twice, once by Lord Cuthan, and then by a lord I’ll not willingly name, my lord, changing it back, so it never went to trial, because the archivist was taking money from both, and the last won. So I’d not believe any record that came to the assizes, my lord, because any could be forged. Some lands have two deeds, both sworn and sealed, and only the neighbors know the truth. So it comes to the court, and so my lord will decide on justice.”

He had not yet dealt with the question of contested lands, of which he knew there were several cases pending, and he found it even more daunting by what Crissand said.

And now he knew at least two things he was sure Crissand had drawn him out here to say, and none of it favoring the Guelen Guard or the viceroy’s rule here. The lord viceroy was gone; but the Guelen captain was not, and since the war needed the Guelen troops, their usefulness presented him a dilemma, two necessities, one for troops, the other simply not to have theft proceeding, especially of equipment.

The province had mustered for the war, he began to understand, and the weapons had just not gone back to the armory: the town was armed, and had been so, and yet the young men had no great skill in using the weapons. Hence so many of them had died at Lewenbrook. He did not like what he heard, not of the treatment of the contents of the armory, not of the forgery of records.

“They should not go on doing this,” Tristen said with firm intent. “They will not go on doing it.”

“Your Guelen clerk has taken no bribes,” Crissand said. “An honest man in office has thrown certain lords into an embarrassing position: the last man to change a document may not be the right man, as everyone knows him to be, and there’s a fear the whole thing will come out. Trust none of Cuthan’s documents, and be careful of Azant’s, on my honor… he’s a good man, my lord, but he’s done what he had to do, to counter Cuthan’s meddling. He regrets it, and now he’s afraid. If Your Grace asked all of them to return the deeds to what they were under Lord Heryn, it might be a fair solution. I say so, knowing I’ll lose and Azant will gain by that, but I think it’s fair, and it would make Azant very happy with Your Grace.”

He heard that. He heard a great many things of like import.

“This is all Levey’s care,” Crissand said finally, as they came over a hill. Gray haze of apple trees showed against the snow, acres of them. “These are their orchards. But the hills about here are sheep pasture… good pasture, in summer. A prosperous village, if it hadn’t lost so many men. The spring’s not far now, my lord.”

The snow had confounded all landmarks. He knew he had ridden past this place before, but it was all strange to his eye, and no villager had stirred, here… the snow ahead of them was pure, trackless, drifted up near the rough stone walls of the orchard.

“Do you hunt, my lord?” The wind picked up, and Crissand pulled up the hood of his cloak. “There’s fine hunting in the woods eastward, past the orchards. Hare and fox.”

“No,” Tristen said, flinching from the thought, the stain on the pure snow. “I prefer not.”

None of your tallow candles, master Emuin had said. Nothing reeking of blood and slaughter. Nothing ever, if he had his way. He had seen blood enough for a lifetime.

There was a small silence. Perhaps he had given too abrupt a refusal. Perhaps he had made Crissand ill at ease, wondering how his lord had taken offense.

“Yet Cook must have something for the kitchens, mustn’t she?” Tristen said, attempting to mend it. “So some will hunt. I don’t prefer it for myself.”

“What do you favor for sport, my lord?”

He blinked at the shifting land above Gery’s ears and tried to imagine all the fair things that filled his idle hours, a question he had asked himself when he saw laughing young men throwing dice or otherwise amusing themselves, cherishing their hounds or hawks.

Or courting young women. He was isolate and unused to fellowship. Haplessly, foolishly, he thought of his pigeons, and the fish sleeping in the pond in the garden, and of his horses, which he valued.

Riding was something another young man might understand, of things that pleased him.

“His Grace is apt to thinking,” Uwen said in his long silence. Uwen was wont to cover his lapses, especially when his lord had been foolish, or frightened people.

“Forgive me,” Tristen said on his own behalf. “I was wondering what I do favor. Riding, I think.” That was closest. So was reading, but it was rarely for pleasure, more often a quest after some troubling concept. “So long as the snow is no thicker than this, we might ride all about the hills and visit all the villages, might we not?”

“Snow never comes deep before Wintertide, not in all my memory.”

“And I had far rather wade through this than answer questions about the doors.”

“As you are lord of Amefel you may have carved what you like, and do what you like. The people do love you. So do we all, my lord, all your loyal men.”

That rang strangely, ominously out of the air, and lightly as he knew it was meant, he felt dread grow out of it, dread of encounters, dread learned where strangers feared other strangers, and encounters were mostly unpleasant. He felt shy, and afraid of a sudden, afraid of his own power over men’s lives. He felt afraid because Crissand felt afraid of him, and it should not be so. The other lords feared him. So did the common folk. He recalled the breaking forth of Sihhë stars on doorways, the cheers in the streets. “Love?” He thought on that a moment.

There was a small silence this time on Crissand’s side. “That you are Sihhë is no fault in their eyes.”

“I am a Summoning and a Shaping,” he said with more directness of his heart than he had ever used on that matter, even with Uwen, who rode close on his other side, Crissand’s captain somewhat back in the column for a word with another man. “That I may be Sihhë seems mere afterthought to being a dead Sihhë.”

“M’lord,” Uwen protested, and Crissand:

“You are our fair lord. None better. None better!”

“A Shaping, and a fool. Uwen knows. Cefwyn’s captain tells me so.”

“Spite.”

“No, I value that in him. And Uwen bears very patiently with my mistakes, knowing all my flaws, and keeps me from the greatest disasters…”

“M’lord!” Even Uwen was scandalized and did not return his fond smile.

“But you do so, and it is true, Uwen. I value your counsel as I value the Lord Commander’s, and your protection above his.”

“M’lord,” Uwen muttered, embarrassed. But it was still true. What Uwen gave him was beyond price or valuation; and he wished ever so much that he might have that kind of honesty from Crissand. He thought he had had it for a moment, and then it had turned to the flattering and the worship Crissand gave him, and he felt that change like a wound.

“Uwen is my friend,” Tristen said to Crissand, riding knee to knee with him, “and Lusin and my guards are my friends, and Tassand and my servants are my friends. And so is king Cefwyn and master Emuin and Her Grace of Elwynor; they know I’m a fool. His Highness Prince Efanor was kind to me, too, and gave me a book of devotions he greatly values. He thinks I’m a heretic. Commander Idrys of the Dragons, too; he calls me a fool and a danger, and I regard his advice. Annas, and Cook, here in Amefel, master Haman, all were kind to me, and I think they regard me as somewhat simple. But Guelessar was a lonely place. Lords, ladies, the servants in the halls and the cook and his men and all, all used to gods-bless themselves and didn’t deal with me.”

“They’re Quinalt,” Crissand said, as if that explained all the world.

“So is Uwen.”

“Not that good a Quinaltine,” Uwen said under his breath.

“And Cefwyn is my friend,” Tristen continued doggedly to his point. “If you wish to be my friend, Crissand Adiran, if you become my friend, you should know that I hold Cefwyn in friendship.”

“For your sake I give up all complaint against him.”

“And will bear him goodwill?”

He had the gift, Emuin had advised him, of both asking and telling too much truth, challenging the polite lies that kept men from inconveniencing each other and the great lies that kept men from each other’s throats. He had learned to moderate that, and wield silence somewhat more often.

But with this young earl who had first met him at sword’s edge and then sworn to him more extravagantly than all the other earls, with this young man who had brought him here to pour half-truths into his ear, he cast down the question like a gage, to see whether Crissand would pick it up or find a polite and empty phrase to avoid allegiance to the Marhanen… and truth to him. Either way, he would thus declare the measure of their friendship.