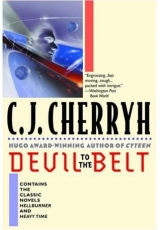

Текст книги "Devil to the Belt (novels "Heavy Time" and "Hellburner")"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 24 (всего у книги 45 страниц)

No official assignment, no cafeteria open at this hour, no card with food privileges. He had fifty on him. Period. And Mr. Lieutenant j-g Jurgen Graff and his unnamed captain hadn’t seen to that detail.

God, he didn’t like the feeling he had. Bet that Graff had contacted Maj. Weiter? Hell if. Bet that the UDC knew where he was right now?

He looked at the phone and thought how he could call the UDC CO here. He could do that. He could break this wide open and maybe be a hero to the UDC—or get caught in the middle of something, behind a security screen that didn’t have Stockholm anywhere inside it. A screen confined to this place. Right now he could plead total ignorance. Right now he had a transfer order signed by Keu and a Security stamp on it and he could plead he had regarded the order exactly the way it said in the Interservice Protocols. And he could do what they wanted and get out of here.

Dammit, he didn’t know why Dekker was crazy. Anybody who wanted to fly little ships and get shot at was crazy. If even the simulator could half kill a guy—

He could have said get Dekker off the drugs. He could have said don’t sedate him—but Dekker knew too much about him, damn him, Dekker knew enough to babble things that could end up on his record, if Dekker got to talking to the psych; and if Dekker had told certain things to Graff, God—Graff could have been sifting everything he had said against information he had no idea Graff had, and weighing it for truth. Graff could have had technical backup doing it, big-time, interactive logic stuff you had no good chance to evade without a clearer head and a calmer pulse rate than he had had in that interview—

God only, what Dekker had involved himself in. Or why someone might have wanted Dekker dead.

Or what might happen if he picked up that phone right now and tried to get through to the UDC office—via hospital communications.

He didn’t know enough about how the lines were drawn here. He didn’t want to know enough. Do what Graff wanted and be on that shuttle on the 22 nd, that was all. Any way he could. And if the UDC did land on him—spill everything immediately. Total innocence. No, sir, they showed me orders, they said it was cleared—

Somebody subbed a pilot on a test run? And somebody put Dekker into a simulator drugged out of his mind?

Bloody hell.

He pulled out the envelope, from inside his jacket. Opened it and pulled out cards and pictures, a couple of licenses and old IDs.

Flight certification. Picture of Dekker and three other people. Group shot. All in Fleet uniform. Woman and two guys besides Dekker. All smiling. Arms over each other’s shoulders.

Old vid advert for a truly skuz sex item. God. We all have our secrets, Dek-lad,...

Picture of Sol Station. Picture of a couple of people outside a trans station. Picture of Mars Base from orbit. If there’d been any of Cory Salazar, Dekker had lost those, a long time ago.

Datacard. The phone had a reader, but he shoved the card into his own. Personal card showed vid rentals. Commissary charges. Postage charges. Bank records. Bits and pieces of Dekker’s life since they’d parted company. Lad had 5300.87cc to his account and no debts. Not bad. Not rich either.

The other datacard was old notes and mail. Not much of it. Notes from various people. One letter months ago from Ingrid Dekker. Four, this last year from Meg Kady.

So Meg did write him. He would never have figured Meg for the letter-writing kind.

Would never have figured Meg for a lot else, either.

He keyed up Meg’s last letter, scanned at random through what must have cost a Shepherd spacer a mint to send:

.. . can’t complain. Doing fine. I’m working into the crew, got myself onto the pilot list. ..

Sal and I dropped into The Hole, just on a look-see. Maybe it’s what we are now. Maybe it’s just the place is duller. It doesn’t feel the same—

So what does? he thought, and thought about Sal, and good times in the Hole’s back rooms. But Sal Aboujib probably had herself a dozen guys on a string by now, swaggering about in rab cut and Shepherd flash, visiting pricey places like Scorpio’s—if Scorpio’s still existed. Sal had her a berth, had her a whole new class of guys to pick from. And Ben Pollard never had gotten a letter from Sal Aboujib. A hello from Dekker once, months ago. He’d said hello back. Only communication they’d had. And it was on here. Hope you’re doing all right. Everything fine. Only long-distance letter he’d ever gotten, tell the truth. And what did you answer, to people you didn’t want to be tied to? Good luck, goodbye, Dekker?

Bills. Note from one Falcone—Dek, we don’t like it either. But nothing we can do right now. They want a show. We’ll sure as hell give them one.

He skimmed back to the letter from Ingrid Dekker. A short one. Don’t come here. I don’t want to see you. You went out there by your own choice and maybe it wasn’t any of it your fault what happened, but things are hard enough. Paul, and I don’t need any more trouble. Stop sending me money. I don’t want any more ties to you. I don’t want any more letters. Leave me alone.

Shit.

He set the reader on his knee, gave a deep breath, thinking– Shit, Dek —He’d grown up on his parents’ insurance himself, both of them having been so careless as to take the deep dive with their whole crew. At first he’d really resented them doing that, thought if they’d given a damn about their kid they wouldn’t have been that careless, but he’d stared into Jupiter’s well himself once—and he knew how subtle and sudden that slope was, in the pit of his stomach he knew it, now, and dreamed about it, on bad nights.

But his mama had never written him a letter like this one, and in that cold little spot marked Who’s left to care, he guessed why Dekker might have written him as next-of-kin: Meg with her letters about how she was working into the crew and everything was going fine for her-Dekker wouldn’t risk having another woman writing him, saying, Get out of my life, you skuz. Dekker already knew what Ben Pollard thought. And if Dekker was in trouble that needed a next-of-kin—whose life was he going to interrupt, who might remotely even know him?

He cut the reader off. He sat there in a cardboard cubby of a room with no damn baggage and for a moment or two had remorseful thoughts about Paul Dekker. Wished maybe he’d written a line or two more, back then, like—hell, he didn’t know. Something polite.

What friggin’ time is it?

Two months in a miner-ship with Dekker off his head asking him the time every few minutes. So here he was back there again—locked into a hospital with Dekker. One part of him felt sorry for Dekker and the other panicked part of him still wanted to beat hell out of the fool and get out of here....

Dammit, what am I supposed to do with this damn card? Why didn’t Graff give this stuff to the psych?

Sub in another pilot, did they? Why, if not Dekker’s attitude? And who did it, if not the CO who’s supposed to want this stuff from Dekker? Real brand-new ship, Dekker said once. That’s why the Fleet had wanted him. He’d been real excited about it—wanted it more than anything in his life—

And a crew’s dead and Dekker’s screwed like that?

He sat there on the side of the bed desperately, urgently, wanting off Sol Two, he didn’t at the moment care where. This whole deal had the stink of death about it.

Serious death, Sal would say.

No shit. Sal. What do I do with the guy?

CHAPTER 3

MR. Graff, urgent word with you. Down the hall. Sir. Please.” 0645 and the breakfast line in the green room was backed up to the door. Hardly time for coffee in the fifteen minutes before he was due in Tanzer’s office and Jurgen Albrecht Graff punched white coffee instead of Mack for his stomach’s sake. “Can it wait?” he asked without looking at Mitch, and caught the cup that tilted sideways and straightened it in time. Held it while it filled. “No, sir. A number of us want to talk, sir. Urgent business.”

Spit and polish. From Mitch. There was no one else in the rec nook of the mess hall and no reasonable chance of being overheard in the clatter of trays. “Tanzer wants to talk, too. I have an appointment in fifteen.”

“Hell.” Mitch was Shepherd, aggressively Shepherd, shaved up the sides, couple of earrings. Bracelet. “I swore you’d be there. Sir.”

Graff lifted out the cup, said, “All right, five,” and stole a sip as he walked with Mitch out the main door and down the hall to the conference rooms. Door to 6a was open. Mitch’s tech crew was there, Pauli and Jacoby, Jamil and his long scanner, Trace. Graff recognized a delegation when he saw it. Tanzer had said, Don’t discuss the hearings. Patently that was not the intention here.

Mitch shut the door. “Sir. We’re asking you to get one of us in front of the committee.”

“Won’t happen,” Graff said. “No chance. You want to get a haircut, Mitch?”

“Hell if.”

“That’s an Earth committee. Blue-sky as they come. They won’t communicate.”

“Yeah,” Jacoby said. “Is that why Tanzer killed Pete and Elly? Couldn’t let a Belter pull it off?”

“Ease off, Jacoby.”

“They won’t let us in hospital. You seen Dekker? You seen him, lieutenant?”

Pauli muttered: “Wouldn’t be surprised if Tanzer ordered him put in that machine. Didn’t want him at the hearings.”

“Shut that down,” Graff said. “Right now.”

Mitch folded his arms, set a foot on a chair, and said, “Somebody better hear it. They didn’t want any Belter son of a bitch in front of the cameras. Dekker couldn’t fly it? Then why didn’t they sub the crew, ask them that!”

“Mitch, I hope somebody does have the brains to ask it. But there’s nothing I can do. They’re not going to ask me that.”

“Hell if, sir! Tanzer’s pets are killing us. You want me to shave up like a—” Mitch looked at him—him and his regulation trim, and shut the epithet off unsaid. “You get me in front of that hearing and I’ll look like a UDC accountant.”

“Mitch, I’m in a position.”

“You’re in a position. You’re running safe behind shields– sir. We’re the ones with our ass on the line.”

Pauli said: “And they can’t automate these sumbitches any further. Why don’t they ask somebody who knows?”

“The designers will. Staatentek’s here. They’ll ask. That much I’ll get a chance to tell them.”

“Ask ‘em about the sim!”

Female voice: Trace. “They’re not interested. This is going to be a whitewash start to finish.”

“The designers have to talk to us, Trace. We’ll get our word in.”

Mitch said: “The engineers have to talk to us. The execs and the politicrats won’t and they have the say.”

“Mitch, I can’t listen to this.”

“Tanzer is a hidebound blue-skyer son of a bitch who thinks because he grew up with a rulebook up his ass is a reason to try to tell any spacer his business or to think that the salute-the-logo dumbasses they’ve pulled in off the Guard and the system test programs could do the job with these ships—”

“They can fly, Mitch.”

“Yeah, they can fly. Like Wilhelmsen.”

“Nothing wrong with Wilhelmsen. Listen to me– Shut it down, and listen: if we have a technical at work, we want to find it, we don’t want to whitewash that either. We have something more at issue here than Wilhelmsen.”

“Yeah,” Pauli muttered. “Tanzer.”

Mitch said, “Nothing wrong with that ship. Everything wrong with the pilot. And they aren’t going to find the solution to what happened to Wilhelmsen in Tanzer’s fuckin’ rulebook. Sir.”

“Let’s just find out, shall we?”

“Just make the point with them, lieutenant: Wilhelmsen wasn’t set with the crew. Wilhelmsen should have said not ready, he was the pilot, he had the final say-so, demo be damned. It was his responsibility to do that.”

“Yes, it was his responsibility, but it wasn’t in his judgment to do it, or he would have done it—the guy’s dead. He got it the same as the rest, Mitch. Let’s give the experts a chance to figure out what.”

“What chance have they got, if they’re not getting the information? Their experts are blue-sky as Tanzer is!”

Jacoby said: “It’s the At-ti-tude in the UDC brass. They murdered Wilhelmsen and Wilhelmsen murdered that crew, that’s what they need to hear!”

“All right! All right! But there’s nothing I can do to get you in there right now, and if you act the fools and screw this, they’ll pull those design changes and you’ll be flying targets. Now leave it! Get off my tail! Give me a chance! That’s the order. I’ve got a meeting.”

There was quiet. It wasn’t a happy quiet. Graff handed the coffee to Mitch. “You drink it.” He started for the door in a dead silence and looked back. “It’s my life too, guys. You shit me, a carrier’s gone. Program’s gone. You understand that?”

They weren’t used to hearing Helm Two talk, like that. Not at all. There were sober faces.

Mitch said, “No offense, lieutenant.”

Graff passed a hand over his close-cropped hair. Said, “Hey, I have to deal with ‘em, guys,” and ducked out, with an uncomfortable feeling of being square in the middle– merchanter and neither Shepherd nor regular UDC. Not part of the rab the EC had exiled to the Belt, not part of the EC, either, in the sense the rab had resisted it—didn’t even understand the politics in the ‘15, but he was getting to.

Fast.

They’d hauled the Shepherd pilots into the Program for their expertise. They weren’t eighteen-year-olds, and they damned sure weren’t anybody’s boys. You didn’t use that word with them. Didn’t lead them, no way in hell. You fed them the situation and showed them where it was different from what they knew. You showed them the feel of it, and let it sink into their bones and they showed the interactive systems new ways to conceptualize. They designed a whole new set of controls around the Shepherds, and software to display what they saw in their insystem-trained heads.

Explain that to Col. Glenn Evan Tanzer, of UDC R&D. God, he wished the captain were back here, that one of the captains would turn up; Kreshov hadn’t shown insystem for weeks; and exactly how it happened that one of the captains wasn’t here at B Dock, at the same time a stray investigative subcommittee had outflanked Keu at Sol and gotten here unchecked—he didn’t know. He couldn’t even swear FteetCom was secure from the UDC code experts. Shepherds thought so, but he wouldn’t commit any more to it man he had.

Not now. Not lately, in Sol System, where the enemy was mindsets that wouldn’t understand the realities in the Beyond. The Belt was closer to The Beyond than it was to Earth.

And closer to it than Tanzer by a far shot. Always Tanzer—who’d been sitting here in R&D so long they dusted him.

0657. By the clock on the wall. He walked down the ^corridor, he walked into Tanzer’s office, and Tanzer’s aide said, “Go right in.”

He did that. He saluted, by the book. Tanzer saluted, they stared at each other, and Tanzer said, “Lt. Benjamin J. Pollard. Does that name evoke memory?”

Shot across the bow. Graff kept all expression off his face. “Yes, sir. Friend of Dekker’s. Listed next-of-kin on his card.”

“Is that your justification for releasing those records to Sol?”

“Captain Keu’s orders, sir. He sees all the accident reports.”

“Is this your justification for issuing a travel voucher?”

“I didn’t issue the travel voucher. Mr. Pollard’s presence here isn’t at my request.”

“Lt. Graff, you’re a hair-splitting liar, you’re a trouble-t. maker and I resent your attitude.”

”On the record, sir, I hardly think I can be held ‘•r. accountable—”

“That’s what you think. You’re sabotaging us, you’re playing politics with my boys’ lives, and you have no authorization to bring in any outsider or to be passing unauthorized messages outside this facility to other commands.”

“That is my chain of command, sir. Dekker is my personnel, and Keu is my commanding officer. Sir. I notify him on all the casualties. What Captain Keu does is not in my control. And if the question arises, I will testify that in my opinion Dekker was not in that simulator by choice. Sir.”

Tanzer’s fist came down on the desk. “I’m in command of this facility, Lt. Graff. The fact that your commander saw fit to leave a junior lieutenant in command of the rider trainees and the carrier does not give you authority over any aspect of this operation, and it does not give you authority to issue passes or to take communications to anyone outside of BaseCom, do you understand me?”

“Where it regards your command, yes, colonel. But I’m responsible to Captain Keu for the communications he directly ordered me to make and which I will continue to make, on FleetCom. Lt, Pollard is here on humanitarian leave in connection with Fleet personnel. He’s Prioritied elsewhere. He’s here temporarily and he has adequate Security clearance to be here.”

“He’s also UDC personnel.”

“He’s under interservice assignment. On leave. And not available to R&D.”

“A friend of Dekker’s. Let me tell you, I’ve had a bellyful of your recruits, and I’m sick and tired of the miner riffraff and psychological misfits washing up on the shores of this program. Your own captain’s interference with design has given this program a piece of junk that can’t be flown—”

“Not true.”

“—a piece of junk that works in the sims and not in the field, lieutenant, because it doesn’t take into account human realities. That firepower can’t be turned over to adrenaline-high games-playing freaks, Mr. Graff, and that machine can’t rely on the 50%’ers on the sims—how many ships are you going to lose on that 50%? Four billion dollars per ship and the time to train the crew and you’re going to gamble that on 50% of the time the pilot’s nerves hold out for the time required? We’re pushing human beings over their design limits, and they’re dying, Mr. Graff, they’re ending up in hospital wards.”

“Wilhelmsen didn’t the of fatigue, colonel, he died of communications failure, he died of not working with his own crew. He schitzed—for one nanosecond he schitzed and forgot where in hell he was in his sequence. There’s an interdict on that move—it’s supposed to be in the pilot’s head, and it failed, colonel, he failed, that’s the bottom line. Dekker—”

“Dekker ran that same flight on sim and he’s lying delirious in hospital. Don’t let me hear you use that word schitz again, lieutenant, except you apply it to your boy. There’s the problem in that crew. There’s the troublemaker that had to prove his point, had to shoot his mouth off—”

“Dekker didn’t run that sim. And the word is concussion, colonel. From the impact of an unsecured body in that pod. He didn’t forget to belt in.”

“He was suited up.”

“The flightsuits keep your feet from swelling, colonel: Dekker’s been exposed to prolonged zero g. The other crews say—”

“He was up there on drugs, lieutenant! Read the medical report! He was high on trank, he was in possession of a tape be had no business with, and he and his attitude got in that pod together, let’s admit what happened up there and quit trying to put Dekker’s smartass maneuver off on any outside agency. There wasn’t one.”

“I intend to find out what did happen.”

“Do you? Do you? Let me lay this word in your lap: either you come up with proof that’ll stand up in court martial, or this investigation is closed. Dekker climbed into that pod on drugs, because he has an Attitude the same as all the other misfits this facility’s been loaded with, he believes he’s cornered the market on right, he’s a smartass who thinks his reflexes make up for his lack of discipline, and if you drop that chaff in the hearing you won’t like the result. If you want this program to fly, and I assume you do, then you’d better reflect very soberly what effect your appearance and your testimony this afternoon is going to have on your captain’s credibility—on the credibility of your service and the judgment of its personnel. Don’t speculate. Keep to the facts.”

“The facts are, Dekker saw what was happening, he called the right moves. It’s on the mission control tape.. ..”

“You’re so damned cocksure what your boys can do, mister, but it’s easy to call the right moves when you’re not the one in the pilot’s seat. You won’t sit those controls. You won’t fly those ships. Will you?”

Fair question, except they’d been over that track before. “That’s exactly the point. I’m not synched to a rider crew. Cross-training would risk both ships.”

“The truth is, lieutenant, your Fleet doesn’t want its precious essential personnel flying a suicide ship, your Fleet won’t let go of its hare-brained concept before it stinks. Your Conrad Mazian isn’t a ship designer, he isn’t an engineer, he’s a merchant captain in a ragtag militia trying to prove it’s qualified for strategic decisions. This ship needs interdicts on a pilot that’s stressing out.”

“That ship needs its combat edge, colonel. If Wilhelmsen had had an AI breathing down his neck he’d have had one more thing on his mind: Is the damned thing going to take my advice or not? At what mission-critical split second that I happen to be right is it going to cut me out of the loop? You can’t cripple a ship with a damned know-it-all robot snatching control away because the pilot pushed the £’s for a reason that, yes, might be knowingly suicidal, for a reason that wasn’t in the mission profile. Besides which, longscan’s after you, and what are you going to do, give a Union longscanner a hundred percent certainty an AI’s going to interdict certain moves? If he knows your cutoffs, he knows your blind spots. If he knows you can’t push it and he can, what’s he going to do, colonel?”

“When the physiological signs are there, you’re going to lose that ship, that’s a hundred percent certainty, and nobody else is going to be exceeding that limit.”

“Wilhelmsen was leaning hard on the Assists. He could have declined that one target, that’s inside the parameters, that’s a judgment a rider’s going to have to make. But he’d have looked bad for the senators. He wanted that target. That’s an Attitude. There’s a use for that in combat. Not for a damned exhibition.”

“Wilhelmsen was saving the program, lieutenant, saving your damned budget appropriation, in equipment that’s got six men in the hospital and seventeen dead. You don’t push machines or human beings past the destruct limit, and you don’t put equipment out there that self-destructs on a muscle-twitch. The pilot was showing symptoms. The AI should have kicked him out of the loop right then, but it can’t do that, you say he can’t have it breathing down his neck—a four-billion-dollar missile with a deadman’s switch, that’s what you’ve got—it needs an integrative AI in there—”

“Watch the pilots cut it off. Which you can’t do with that damned tetralogic system you’re talking about, it’s got to be in the loop talking to the interactives constantly, and no matter the input it got after, its logic systems are exactly the same as the next one’s, same as the ships are. The only wildcard you’ve got is the humans, the only thing that keeps the enemy longscanners guessing. The best machine you’ve got can’t outguess the human longscanner—why should you assume they’re going to outperform the pilot?”

“Because the longscanner can’t kill the crew.”

“The hell he can’t!”

“Not in that sense.”

“Your tests don’t simulate combat. That’s what we’ve been telling you—you keep concentrating on the fire rate, always the damned fire rate and you’re not dealing with the reason we recruited these particular crews. Nobody at Lendler Corp has been in combat, none of your pilots have been, the UDC hasn’t been, since it was founded—your tests are set up wrong!”

Not saying Tanzer himself hadn’t been in combat. Red in the face, Tanzer got a breath. “Let’s talk about exceeding human limits, lieutenant: what happened out there was exactly why we’ve got men in hospital over there who can’t walk a level floor without staggering, it’s why we’ve had cardiac symptoms in men under thirty, and those aren’t from four-hour runs.” A jab of the finger in his direction. “Let me tell you, lieutenant, I’ve met the kind of attitude your command is fostering among the trainees. Show-outs and ego-freaks. And I wish them out of my command. You may have toddled down a deck in your diapers, and so may Mazian’s ragtag enlistees out of the Belt, but how are you going to teach them anything when they already know it all and you acquired your know-how by superior genes? You can’t lose 50% of your ships and crews at every pass. 96% retrievability, wasn’t that the original design criterion? Or isn’t that retrievability word going to be in the manual when we put this ship on the line?”

“If a Union armscomper gets your numbers you have zero retrievability, colonel, that’s my point. You have to exceed your own numbers, you have to surprise your own interfaces in order to surprise that other ship’s computers and that means being at the top of the architecture of your Adaptive Assists. The enemy knows your name out there. Union says, That’s Victoria, that’s Btzroy or Graff at Helm, because Victoria wouldn’t go in with Helm Three. They know you and they know your style, and it’s in their double A’s, but you innovate and they innovate. One AI sitting on top of the human and his interfaces is like any other damn AI sitting on top of the interfaces—there aren’t that many models, the enemy knows them all, and the second its logic signature develops in the enemy’s intelligence about you, hell, they’ll have a fire-track lying in wait for you.”

“Then you’d better damn well improve your security, hadn’t you?”

“Colonel, there are four manufacturers in friendly space for this tetralogic equipment and we can’t swear there’s not an Eye sitting right outside the system right now. Any merchanter who ever came into system could have dropped one, before the embargo, and it’s next to impossible to find it. Merchanters are your friends and your enemies: that’s the war the Company made, and that’s what’s going on out there—they don’t all declare their loyalties and a lot of them haven’t got any, not them and not us. They’ll find out the names. They’ll find out the manufacturers and the software designers. They’ll learn us. That’s a top priority—who’s at Helm and who’s in command, and if it’s even one in four brands of tetralogic—”

“All the more reason for interchangeable personnel.”

“It’s doesn’t work that way! You don’t go into an engagement with anybody who just happens to be on watch. You try to get your best online. No question. You don’t trade personnel and you don’t trade equipment. You haven’t time at .5 light coming down off jump to think about what ship you’re in or what crew you’re with. I’m telling you, colonel, my captain has no wish to raise the substitution as an issue against your decisions, but on his orders, as judiciously as I can, I am going to make the point that it was a critical factor. We cannot integrate a computerized ship into our operations. In that condition it is no better than a missile.”

“You haven’t the credentials to say what it is and isn’t, lieutenant. You’re not a psychiatrist and you’re not a computer specialist.”

“I am a combat pilot. One of two at this base.”

A cold, dark silence. “I’ll tell you—if you want to raise issues this afternoon, I’m perfectly willing to make clear to the committee that you’re a composite, lieutenant, a shell steered by non-command personnel and an absentee captain, and you clearly don’t have the administrative experience to handle your own security, much less speak with expert knowledge on systems you’ve never seen. I’ve held this office for thirty years, I’ve seen all sorts of games, and your commanding officer’s leaving that carrier to subordinates and your own abuse of your commanding officer’s communications privileges is an official report in my chain of command. This is not the frontier, this is not a bare-based militia operation, and if your service ever hopes to turn these trainees into competent military personnel you can start by setting a personal example. Clean up your own command and stop fomenting dissension in this facility!”

“I do not accept that assessment.”

“Then you can leave this office. And if you are called on to testify, you’ll be there as one of the pilots personally involved in the accident, not as a systems expert. You’d be very unwise to push past that position—or you’ll find questions raised that could be damned embarrassing to your absentee superior and your entire service. I’m talking about adverse publicity, if you give grounds to any of these senators or to the high command. Do you understand that? Because I won’t pull any punches. And the one security no one can guarantee is a senator’s personal staff.”

“Are you attempting to dictate my testimony, colonel? Is that what I’m hearing?”

“In no wise. Give my regards to your captain. Good day, lieutenant.”

Something had come loose. Banging. The tumble did that. Dekker reached after the cabinet, tried to get to the com.

Hand caught his arm. Something shoved him back and he hit pillows.

Bang from elsewhere.

“Hey, Dek. You want eggs or pancakes?”

He couldn’t figure how Ben had gotten onto the ship. Ben had rescued him. But he didn’t remember that.

“Eggs or pancakes?”

“Eggs aren’t real,” he said. “Awful stuff.”

“They’re real, Dek-boy. Not to my taste, living things, but they’re real enough to upset my stomach. Eggs, you want? Orange juice?”

He tried to move. Usually he couldn’t. But his arms were free. He stuffed pillows under his head and Ben did something that propped the head up. Ben went out in-the hall and came back and set a tray down on the table, swung it over him.

“Eat it. That’s an order, Dek-boy.”

He picked up a fork. It seemed foreign, difficult to balance in .9 g. His head kept going around. His arm weighed more than he remembered and it was hard to keep his head up. But he stabbed a bit of scrambled egg and got a bite down. Another. He reached for the orange juice but Ben did it for him, took a sip himself beforehand and said, “We got better at Sol One.”

Maybe it was. Maybe he was supposed to know that. Ben held the cup to his lips and he sipped a little of it. It stung cuts in his mouth and it hit his stomach with a sugar impact.

“Keep it up, Dek-boy, and they’ll take that tube out.”