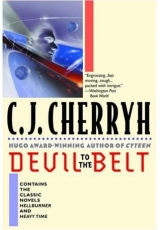

Текст книги "Devil to the Belt (novels "Heavy Time" and "Hellburner")"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 45 страниц)

Bird shoved over to the lifesupport control panel and cut the siren. The silence after was deafening. Just the shower going and their own hard breathing.

Ben was a hard worker, sometimes too hard. Bird told himself that, told himself Ben was a damned fine partner, and the Belt was lonely and tempers got raw. Two men jammed into a five by three can for months on end had to give each other room—had to, that was all.

Ben said, thin-lipped, but sanely, “Bird, we got to wipe down these suits. We have to get this stink off. It’s going to break down our filters, dammit.”

“It won’t break down our filters,” Bird assured him quietly, but he went and got the case of towel wipes out of the locker. The shower entered its drying cycle. The guy was floating there, eyes shut, maybe resting, maybe unconscious. Bird reached for the door.

Ben held the latch down and pushed the Test Cycle a second time.

“Ben,” Bird protested, “Ben, for God’s sake, the guy’s had enough. Are you trying to drown him?”

“I won’t live with that stink!”

The man—kid, really, he looked younger than Ben was—had drifted against the shower wall and hung there. He was moving again, however feebly—and maybe it was cowardly not to insist Ben listen to reason, but a small ship was nowhere to have a fight start, over what was likely doing the kid no harm, and maybe some good. You could breathe the mist, you could drink the detergent straight and not suffer from it. Dehydrated as he was, he could do with a little clean water; and cold as he’d been, maybe it was a fast way to warm him through.

So he said, “All right, all right, Ben,” and opened the box of disinfectant towels, wiped his hands and chest and arms and worked down.

“I can still smell it,” Ben said in a shaky voice, wiping his own suit off. “Even after you scrub it I can still smell it.”

“That’s just the disinfectant.”

“Hell if it is.”

Ben was not doing well, Bird thought. He had insisted Ben go over there with him and maybe that had been a mistake: Ben wasn’t far into his twenties himself; and Ben might never have been in a truly lonely, scary situation in his whole stationbound life. Ben had spooked himself about this business for days, with all this talk about hijackers.

On the other hand maybe an old dirtsider from Earth and a Belter brat four years out of school weren’t ever going to understand each other on all levels.

They shed the suits. They’d used up three quarters of their supply of wipes. “Just as well our guy stays in the shower,” Bird said, now that he thought calmly about it, “until we have something to put him in. His clothes’ll be dry in a bit.” He cycled the shower again himself, stowed his suit and floated over to the dryer as it finished its cycle. The clothes were a little damp about the seams, and smelled of disinfectant: the dryer’s humidity sensor needed replacing, among a dozen other things at the bottom of his roundtoit list. He read the stenciled tag on the coveralls. “Our guy’s got a name. Tag says Dekker. P.”

“That’s fine. So he’s got a name. What happened to his partner, that’s what I want to know.”

Maybe that was after all what was bothering Ben—too many stories about Nouri and the hijackers.

“He wasn’t doing so well himself, was he?” Dekker, P was drifting in the shower compartment, occasionally moving, not much. Bird opened the door, without interference from Ben this time, and said, quietly, before he took the man’s arm: “Dekker, my name’s Bird, Morrie Bird. My partner’s Ben. You’re all right. We’re going to get you dressed now. Don’t want you to chill.”

Dekker half opened his eyes, maybe at the cold air, maybe at the voice. He jerked his arm when Bird pulled him toward the outside. “Cory?” he asked. And in panic, bracing a knee and a hand against the shower door rim: “Cory?”

“Watch him!” Ben cried; but it was Ben who caught a loose backhand in the face. Dekker jabbed with his elbow on the recoil, made a move to shove past them, but he had nothing left, neither leverage nor strength. Bird blocked his escape and threw an arm around him, after which Dekker seemed to gray out, all but limp, saying, “Cory…”

“Must be the partner,” Bird said.

“God only. I want a shower, Bird.” Ben snatched the half-dry coveralls from him and grabbed Dekker’s arm. “Hell with the stimsuit, let’s just wrap this guy up before he bashes a panel or something.”

“Just hold on to him,” Bird said. Bird caught the stimsuit that was drifting nearby, shook the elastic out, got the legs and sleeves untangled and got hold of Dekker’s arm. “Left leg, come on, son. Clean clothes. Come on, give us some help here. Left leg.”

Dekker tried to help, then, much as a man could who kept passing out on them. His skin had been heated from the shower. It was rapidly cooling in the cabin air and Ben was right: it was hard enough to get a stimsuit on oneself, nearly impossible to put one on a fainting man. He was chilling too fast. They gave that up. By the time they got him into the coveralls and zipped him up he was moving only feebly, half-conscious.

“Not doing real well, is he?” Ben said. “Damn waste of effort. The guy’s going to sign off—”

“He’s all right,” Bird said, “God, Ben, mind your mouth.”

“I just want my bath. Let’s just get this guy to bed, all right? We get a shower, we call Mama and tell her we got ourselves a ship!”

“Shut up about the ship, Ben.”

A long, careful breath. “Look, I’m tired, you’re tired, let’s just forget it til we get squared away, all right?”

“All right.” Bird shoved off in a temper of his own, drifted toward the spinner cylinders overhead, taking Dekker with him—carefully turned and caught a hold, pulling Dekker toward the open end. “Come on, son, we’re putting you to bed, easy does it.”

Dekker said, “Cory,—”

“Cory’s your partner?”

Dekker’s eyes opened, hazed and vague. Dekker grabbed the spinner rim, shaking his head, refusing to be put inside.

“Dekker? What happened to you, son?”

“Cory,—” Dekker said, and shoved. “I don’t want to. No!”

Ben sailed up, grabbed Dekker’s collar on the way and carried him half into the cylinder, Dekker fighting and kicking. Bird rolled and pushed off, got Dekker by a leg, Dekker screaming for Cory all the while and fighting them.

“Hold on to him!” Ben said, and Bird did that, holding Dekker from behind until Ben could unhook a safety tether from the bulkhead, held on while Ben sailed back to grab Dekker’s arm and tie it to a pipe.

“Damn crazy,” Ben said, panting. “Just keep him there. I’ll get another line.”

“That’s rough, Ben.”

“Rougher on all of us if this fool hits the panels. Just hold him, dammit!”

Ben somersaulted off to the supply lockers, while Bird caught his breath and kept Dekker’s free arm pinned, patting his shoulder, saying, “It’s all right, son, it’s all right, we’re trying to get you home. My name’s Bird. That’s Ben. What do you go by?”

Several shallow breaths. Struggles turned to shivers. “Dek.”

“That’s good.” He patted Dekker’s shoulder. Dekker’s eyes were open but Bird was far from sure Dekker knew where he was or what had happened to him. “Just hold on, son.” A locker door banged, forward. Ben came sailing up with a roll of tape.

“I’m not sure we need that,” Bird said. “Guy’s just a little spooked.”

Ben ignored him, grabbed Dekker’s other arm and began wrapping it to the pipe. “Guy’s totally off his head.” Dekker tried to kick him, Dekker kept saying, “My partner—where’s my partner?”

“Afraid there was an accident,” Bird said, holding Dekker’s shoulder. “Suit’s gone. We looked. There wasn’t anybody else on that ship.”

“No!”

“You remember what happened?”

Dekker shook his head, teeth chattering. “Cory.”

“Was Cory your partner?”

“Cory!”

“Shit,” Ben said, and shook Dekker, slapped his face gently. “Your partner’s dead, man. The suit was gone. You got picked up, my partner and I picked you up. Hear?”

It did no good. Dekker kept mumbling about Cory, and Ben said, “I’m going down after a shower. Or you can.”

“I’m scared we left somebody in that ship.”

“You didn’t leave anybody in that ship, dammit, Bird, we’re not opening that lock again!”

“I’m not that sure.”

“You looked, Bird, you looked. If there was a Cory he’s gone, that’s all. Suit and all. We’ve done all we can for this guy. We’ve spent days on this guy. We’ve spent our fuel on this guy, we’ve risked our necks for this guy—”

“His name’s Dekker.”

“His name’s Dekker or Cory or Buddha for all I care. He’s out of his head, we got nowhere safe to put him, we don’t know what happened to his partner, we don’t know why Mama doesn’t know him, and that worries me, Bird, it seriously does!”

It made sense. Everything Ben was saying made sense. The other suit was gone. They had searched the lockers and the spinners. There were no hiding places left. But nothing about this affair was making sense.

“Hear me?” Ben asked.

“All right, all right,” Bird said, “just go get your shower and let’s get our numbers comped. We have to call in. Have to. Regulations. We got to do this all by the book.”

“Don’t you feel sorry for him. You hear me, Bird? Don’t you even think about going back into that ship.”

“I won’t. I don’t. It’s all right.”

Ben looked at him distressedly, then rolled and kicked off for the shower.

Bird floated down to the galley beside it, opened the fridge and got a packet of Citrisal, lime, lemon, what the hell, it was all ghastly awful, but it had the trace elements and salts and simple sugars.

It was the best he knew to do for the man. He drifted over to Dekker, extracted the tube and held it to Dekker’s lips.

“Come on. Drink up. It’s the green stuff.”

Dekker took a sip, made a face, ducked his head aside.

“Come on. Another.”

Dekker shook his head.

Couldn’t blame him for that, Bird thought. And you damn sure didn’t want anybody sick at his stomach in null-g. He tested whether the cord and the tape were too tight, decided Dekker was all right for a while. “Well let you loose when your head clears. You’re all right. Hear me? We’re going to get you back to Base. Get you to the meds. Hear me?”

Dekker nodded slightly, eyes shut.

Exhausted, Bird decided. He gave the man a gentle pat on the shoulder and said, “Get some sleep. Ship’s stable now.”

Dekker muttered something. Agreement, Bird thought. He hoped so. He was shaky, exhausted, and he wished they were a hell of a lot closer to Base than they were.

The guy needed a hospital in the worst way. And that was a month away at least. Bad trip. And there was the investment of time and money this run was going to cost them. Half a year’s income, counting mandatory layouts.

Maybe Ben was right and they did have a legal claim on this wreck—Ben was a college boy, Ben knew the ins and outs of company law and all the loopholes—and maybe legally those were the rules, but Bird didn’t like thinking that way and he didn’t like the situation this run had put them in. If it was a company ship they had in tow and if it was the company itself they were going to be collecting their bills from—that was one thing; but the rig with its cheap equipment wasn’t spiff enough for a company ship. That meant it was a freerunner, and that meant it was some poor sod’s whole life, Dekker’s or somebody’s. Get their expenses back, yes, much as they could, but not rob some poor guy of everything he owned. That wasn’t something Bird wanted to think about.

But Ben could. And Ben scared him of a sudden. You worked with a guy two years in a little can like this and eventually you did think you knew him reasonably well, but God knew and experience had proved it more than once—it was lonely out here, it was a long way from civilization, and you could never realize what all a guy’s kinks were until something pushed the significant button.

CHAPTER 2

THE old man went away. Dekker heard him or his partner moving about. He heard the shower going, over the fan and the pump noises in the pipes beside his head. The ship was stable. That was a feeling he had thought he would never have again. He had dimmed the lights, cut off everything he could and nursed it as far as he could til the ‘cyclers went and the water fouled.

And here he was free of the stimsuit, light as a breeze and vulnerable to the chill and the lack of g. He was off his head, he knew that: he scared the people who had rescued him, he knew that too, and he tried not to do it, but they scared him. They talked about owning his ship. They might kill him, might just let him die and tell the company sorry, they hadn’t been able to help that.

Maybe they couldn’t. Maybe he shouldn’t care any longer. He was tired, he hurt, body and soul, and living took more work than he was sure he wanted to spend again on anything. He had no idea how long and how far a run was still in front of him getting home. He didn’t think he could stand being treated like this all the way. Everything smelled of disinfectant, and sometimes it was his ship and sometimes it was theirs.

But Cory never answered him wherever he was, and at times he knew she wouldn’t.

The old man drifted up into his sight again, put a straw in his mouth and told him to drink. He did. It tasted of copper. The old man asked him what had happened to his partner. Then he remembered—how could he have forgotten?—that she was out there and that ship was, he could see it coming—

“No!” he cried, and winced when it hit, he knew it was going to hit, the collision alert was screaming. He yelled into the mike, “My partner’s out there!” because it was the last thing he could think of to tell them.

“Your partner’s dead!” somebody yelled at him, and another voice, angry, yelled, “Shut up, dammit, Ben! You got no damn feelings, give the guy a chance. God!”

He was still alive and he did not understand how he had survived. He hauled himself to the radio, he held on against the spin as long as he had strength. “Cory,” he called on the suit-com frequency, over and over again, while the ship tumbled. Maybe she answered. His ears rang so he couldn’t hear the fans or the pumps. But he kept calling her name, so she would know he was alive and looking for her, that he’d get help to her somehow…

As soon as he could get the damned engines to fire.

Or as soon as he could get hold of Base and make that ship out there answer him…

Ben said, “We’re duesalvage rights, whether he’s company or a freerunner, no legal difference. It’s right in the company rules, I’ll show you—”

Bird said, carefully, because he wanted Ben to understand him: “We’ll get compensated.”

“Maritime law since—”

“There’s the law and there’s what’s right, Ben.”

“ Rightis, we own that ship, Bird. He wasn’t in control of it, that’s what rightsays.”

Ben was short of breath. He was yelling. Bird said, calmly, sanely, “I’m trying to tell you, there’s a lot of complications here. Let’s just calm down. We’ve got weeks yet back to Base, plenty of time to figure this out, and we’ll talk about it. But we’re not getting any damn where if we don’t get our figures in and tell Mama to get us the hell home. Fast.”

“So how much are you going to spend on this guy?. A month’s worth of food? Medical supplies? We’re going to bust our ass and risk our rigging for this guy?”

Bird had no answer. He couldn’t think of one to cut this off.

“This is my money too, Bird. It’s my money you’re spending. Maybe you own this ship, maybe I’m just a part-share partner, but I have some say here.” Ben flung a gesture toward Dekker, aft. “That guy’s going to live or he’s going to die. In either case he’s going to do it before the month is up. Much as I want to be rid of him, there’s no need busting our tails—we have double mass to move, Bird, and hell if I’m dumping the sling—”

“All right, we’re not dumping the sling. Not ours, not his either, if we can avoid it.”

“And we’re not putting any hard push on the rigging. There’s no point in risking our necks. Or putting wear on the pins and the lines. We don’t call this a life-and-death. We can’t cut that much time off. And hell if I want to meet a rock the way this guy did.”

It made better sense than a lot else Ben had been saying. Bird took that for hopeful and nodded. “I’ll go with you on that. A hard push could do more harm than good for him, too.”

“Guy’s going to die anyway.”

“He’s not going to die,” Bird said. “For God’s sake, just shut up, he can hear you.”

“So if he doesn’t? A month gets him well, and we pull into station and he looks healthy and he says sure he was managing that ship just fine—”

“Just let it alone, Ben!”

“I’m going to get pictures.”

“Get your pictures.” Bird shook his head, wishing he could say no, wishing he had some way to reason with Ben, but if getting a vid record would make Ben happier, God, let him have the pictures. “We have the condition of that ship out there, we have the log records over there—”

“Charts—” Ben exclaimed, as if that was a new idea.

“We’re not touching that log. No way. That part of the law Iknow.”

“I’m not talking about that. Look—look, I got an idea.”

An idea was welcome. Bird watched doubtfully as Ben punched up the zone schema, pointed on the screen to the’driver ship and its fire-path to the Well, the same thing that scared them even to contemplate. “ That’sgot a medic. That’s got a friggin’ company captain in charge. We just ask Mama to boost us over there just across the line and theycan take official possession.”

“Damn right they would. The company doesn’t run a charity.”

“It’s an Rl ship! They’re obligated to take him. They have no choice. The law says a ‘driver is a Base: they can log us right there for a find if we bring it in, and this is a find, isn’t it? Same as a rock. We can turn it in, money in the bank, and we can apply to do some clean-up along with its tenders for the rest of our run—that’s damn good money. Sure money. And we got the best excuse going.”

“Ben, that’s a ‘driver captain you’re talking about. They don’t haveto do anything. You want him to tell us we’ve still got to turn around and take this guy in to Base, maybe clean to Rl, if he takes it in his head—he can do that. You want him to tell us he’ll hold Eighty-four Zebra for us—and then contest his fees in court when he shows up three years from now with one hell of a haulage charge? We got this run to pay for, we got serious questions to answer, because there’s a whole lot that’s not right about this, and I’m not taking my chances with any Court of Inquiry back at Base with all the evidence stuck out on a ‘driver that for all we know isn’t coming in for three or four more years. If you want to talk law, now, let’s be practical!”

Ben’s mouth shut.

“A ‘driver does any damn thing it wants to. Three years’ dockage charges, supposing they’re on the start of their run. Three years’ haulage. You want to try to pry a claim away from the company then? Not mentioning the cost of getting it there. We’re short as is. You want to hear them say ferry it back ourselves anyway? Twice the distance? Or get us drafted into its tender crew on a permanentbasis? You know what they charge a freerunner for fuel?”

Ben looked very sober during all of this. Ben bit his lip. “So that’s out. You know, we could just sort of knock that fellow on the head. Solve everybody’s problem.”

Ben, who was scared to death of looking at a body.

“Yeah, sure,” Bird said.

And from aft: “What time is it? What’s the time?”

Ben glanced up. “Now what does he want?”

Bird checked his watch. “2310,” he shouted back.

“I want my watch.”

“God,” Ben muttered, shaking his head. “We have four weeks of this guy?”

“ I want my watch!”

Ben yelled: “Shut up, dammit, you’re not keeping any appointments anyway!”

“Patience,” Bird said, but Ben shoved off in Dekker’s direction. Bird sailed after, arrived as Dekker said quietly, “I need my watch.”

Ben said: “You don’t need your watch, you’re not going anywhere. It’s 23 damn 10 in my sleep, mister, you’re using our air and our fuel and our time already, so shut up.”

“Ben, just take it easy.”

“I’ll shut him up with a wrench.”

“Ben.”

“All right, all right, all right.” Ben took off again.

Dekker said, “I can’t see my watch.”

Bird floated over where he could read the time on Dekker’s watch. “2014. You’re about three hours slow.”

“No.”

“That’s what it says.”

“What day is it?”

“May 20.”

“You’re lying to me!”

“Bird,” Ben said ominously, and came drifting up again to reach for Dekker, but Bird grabbed him.

“I can’t take four weeks of that, Bird, I swear to you, this guy’s already on credit with me already.”

“Give mea little slack, will you? Shut it down. Shut it up. Hear me?”

“I’ve dealt with crazies,” Ben muttered. “I’ve seen enough of them.”

“Fine. Fine. We get this guy out of a tumble, he’s been whacked about the head, he’s a little shook, Ben, d’you think you wouldn’t be, if you’d been through what he has?”

Ben stared at him, jaw clamped, grievous offense in every line of his face.

Ben was in the middle of his night. That was so. Ben was tired and Ben had been spooked, and Ben didn’t understand weakness in anybody else.

Serious personality flaw, Bird thought. Dangerous personality flaw.

He watched Ben go back to his work without a word.

Good partner in some ways. Damned efficient. Good with rocks.

But different. Belter-born, for one thing, never talked about his relatives. Brought up by the corporation, for the corporation.

Talk to Ben about Shakespeare, Ben’d say, What shift does he work?

Say, I come from Colorado—Ben’d say, Is that a city?

But Ben didn’t really know what a city was. You couldn’t figure how Ben read that word.

Say, I went up to Denver for the weekend, and Ben’d look at you funny, because weekend was another thing that didn’t translate. Ben wouldn’t ask, either, because Ben didn’t really want to know: he couldn’t spend it and he wasn’t going there and never would and that was the limit of Ben’s interest.

Ask Ben about spectral analysis or the assay and provenance of a given chunk of rock and he’d do a thirty-minute monologue.

Damn weird values in Belt kids’ mindsets. Sometimes Bird wondered. Right now he didn’t want to know.

Right now he was thinking he might not want Ben with him next trip. Ben was a fine geologist, a reliable hold-her-steady kind of pilot, and honest in his own way.

But he had some scary dark spots too.

Maybe years could teach Ben what a city was. But God only knew if you could teach Ben how to live in one.

Bird was seriously pissed. Ben had that much figured, and that made him mad and it made him nervous. He approved of Bird, generally. Bird knew his business, Bird had spent thirty years in the Belt, doing things the hard way, and Ben had had it figured from the time he was 14 that you never got anywhere working for the company if you weren’t in the executive track or if you weren’t a senior pilot: he had never had the connections for the one and he hadn’t the reflexes for the other, so freerunning was the choice… where he was working only for himself and where what you knew made the difference.

He had come out of the Institute with a basic pilot’s license and the damn-all latest theory, had the numbers and the knowledge and everything it took. The company hadn’t been happy to see an Institute lad go off freerunning, instead of slaving in its offices or working numbers for some company miner, and most Institute brats wouldn’t have had the nerve to do what he’d done: skimp and save and live in the debtor barracks, and then bet every last dollar on a freerunner’s outfitting; most kids who went through the Institute didn’t have the discipline, didn’t refrain from the extra food and the entertainment and the posh quarters you could opt for. They didn’t even get out of the Institute undebted, thank Godfor mama’s insurance; and even granted they did all that, most wouldn’t have had the practical sense to know, if they did decide to go mining and not take a job key-pushing in some office, that the game was not to sign up with some shiny-new company pilot in corp-rab, who had perks out to here. Hell, no, the smart thing was to hunt the records for the old independent who had made ends meet for thirty years, lean times and otherwise.

Namely Morris Bird.

Freerunning was the only wide gamble left in the Belt—and freerunners, being from what they were, didn’t have the advantage of expert, up-to-date knowledge from the Institute—plus the Assay Office. But with Morrie Bird’s thirty years of running the Belt, his oldcharted pieces were bigger than you got nowadays, distributed all along the orbital track, and he got chart fees on those every month, the company didn’t argue with his requests to tag, and those old charted pieces kept coming round again, in the way of rocks that looped the sun fast and slow. Sometimes those twenty-four– and twelve-year-old pieces might have been perturbed, and if somebody tried to argue about the claim, your numbers had to be solid after all those years—besides which, to find the good chaff that might remain to be found, you had to have more than guesswork. That was the pitch he had to offer along with 20 k interest-free to finance some equipment Bird badly needed; that was why Bird should take a greenie for a numbers man in a time when experienced miners went begging: company training, the science and the math and the complete Belt charts that Assay got to see—and they had done damned well as a team– damnedwell, til they’d got one of those absolutely miserable draws Mama sometimes handed you—a sector where there just wasn’t much left to find but a handful of company-directed tags on some company-owned rocks.

So right now they were in a financial slump, Bird was under a strain, and Bird had odd touchy spots Ben never had been able to figure—all of which this Dekker had evidently hit on with his crazy behavior and his pretty-boy looks. Dekker was up there in their sleeping nook mumbling about losing his partner (damned careless of him!) and now Bird was mad at him, acting as if it was hisfault the guy was alive and the find that might have been their big break turned out complicated.

Maybe, he thought, Bird did want that ship as much as he did, maybe Bird was equally upset that this fellow was alive, Bird having this ethic about helping people—Bird might well be confused about what he was feeling.

Dangerous attitude to spread around, Ben thought, this charity business—and unfair, when Bird even thought about forgoing that ship for somebody who owed him and not the other way around, at his own partner’s expense. It was a way for Bird to get had, and a man as free-handed as Bird was needed help from a partner with a lasting reason to keep him in one piece.

“Bird?” he called out from the workstation. “I got your prelim calc. No complications but that ‘driver and our mass.”

Bird came over to him, Bird said he’d finish it up and call Mama. Bird touched him on the shoulder in a confusingly friendly way and said, “Get some sleep.”

Ben said, because he thought it might make Bird happier, “You. I’m wired.” At the bottom of his motives was the thought that a little time next to Dekker’s constant mumbling about Cory and his watch might make Bird a little less charitable to strangers.

But Bird said, “You. You’re the one needs it most.”

“What’s thatsupposed to mean?”

“It means what it means. You’re tired. You’ve worked your ass off Get some rest.”

“I don’t think I’ll sleep right off. That guy makes me nervous. This whole situation makes me nervous.”

“Bad day. Hard day.”

He decided Bird was being sane again. He was relieved. “You know,” he said, “we might just ought to get a statement out of this guy. You know. Besides pictures. I’m going to get a tape of this whole damn What-time-is-it? routine, show what we got to cope with. Might just prove our case.”

Bird shook his head.

“Bird, for God’s sake.”

“Ben,” he said firmly.

Ben did not understand. He flatly did not understand.

“Just go easy on him,” Bird said.

“So what’s he to us?”

“A human being.”

“That’s no damn recommendation,” Ben muttered. But it was definitely a mistake to argue with Bird in his present mood: Bird owned the ship. Ben shook his head. “I’ll just get the pictures.”

“You don’t understand, do you?”

“Understand what?”

“What if it was you out there?”

“I wouldn’t be in that damn mess, Bird! You wouldn’t be.”

“You’re that sure.”

“I’m sure.”

“Ben, you mind my asking—what ever happened to your folks?”

“What’s that to do with it?”

“Did theyever make a mistake?”

“My mama wasn’t the pilot.—That ship’s not going to be book mass, with that tank rupture. Center of mass is going to be off, too. Need to do a test burn in a little while, all right? I don’t want to leave anything to guesswork.”

“Yeah. Fine. Nothing rough. Remember we have a passenger.”

Ben frowned at him, and kept his mouth shut.

Bird said, pulling closer, “I got to tell you, Ben, right up front, we’re not robbing this poor sod. He’s got enough troubles. Hear me? Don’t you even be thinking about it.”

“It’s not robbing. It’s perfectly legal. It’s your rights, Bird, same as he has his. The same as he’d take his, if things were the other way around. That’s the way the system is set up to work.”

“There’s rights, and there’s what is right.”

“He’s not your friend! He’s not even anybody’s friend you know. Bird, for God’s sake, you got a major break here. Breaks like this don’t just fall into your lap, and they’re nothing if you don’t make them work for you. That’s why there’s laws—to even it up so you can work with people the way they are, Bird, not the way you want them to be.”

“You still have to look in mirrors.”

“What’s mirrors to do with anything?”

“If we’re due anything, we’re due the expenses.”

“Expenses, hell! We’re due haulage, medical stuff, chemkit, and a fat salvage fee at minim, we’re due that whole damn ship, is what we’re due, Bird.”

“It won’t work.”

“Hell if it won’t work, Bird! I’ll show it to you in the code. You want me to show it to you in the code?”

Bird looked put out with him. Bird said, with a sigh, “I know the rules.”

Bird had him completely puzzled. He took a chance, asked: “Bird,—have I done something wrong?”

“No. Just give me warning on that burn. I’m going to shoot some antibiotics into our passenger, get him a little more comfortable.”