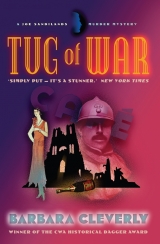

Текст книги "Tug of War"

Автор книги: Barbara Cleverly

Жанр:

Классические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

Varimont settled behind the desk in his well-ordered room, rearranged a neat pile of folders and smoothed down one side of his trim moustache and then the other. He glanced at a wall clock. ‘Five o’clock! Perfect timing! We ’ll have English tea.’ And, without a signal given, the door opened to admit an orderly carrying a tray. ‘One more cup please, Eugène.’

Eugène nodded and went off at the double to fetch it.

When the doctor was happy with the parade of crockery and the timing of the brew, he invited Dorcas to officiate and, while she busied herself happily with this familiar task, he launched at once into the case.

‘Before I take you to see the patient, a briefing, I think? Tell me, to save our time, what you already know of our poor unfortunate.’

Joe outlined his knowledge, rather underplaying the extent of it and claiming no acquaintance with the medical aspects of shell-shock. ‘I am here, sir,’ he summarized, ‘to explore the implications of your recent revelations regarding the man’s country of origin. To try to answer the question, “Is he English?” No more than that. If he proves to be such, arrangements will be made to convey him to a suitable establishment over the Channel and the onus will then be on the English authorities to assign an identity. Tell me – apart from the language used during the nightmare – are there any other indications that he may be something other than French? Many races took part in the war.’

‘None that I can discover.’ The doctor stirred uneasily. ‘Look – he’s not a new arrival, you understand. This is not the first hospital he has fetched up at since repatriation. We are just the first ones to interest ourselves in identifying and solving his problems. He has been passed along, shedding, doubtless, any information . . . clues . . . clothing . . . at each move. I’ve attempted to back-track but it’s hopeless. I’ve got as far as an asylum in the Ardennes in 1922. Records start there. It’s thought he was a late repatriation from Germany. They merely record him as a French soldier sent back without papers or identity. He was wearing the usual German-issue undergarments with a threadbare French army greatcoat on top. No insignia on it and, of course, it may not even have been his. The only clue – and it may be misleading – was a piece of card with German lettering on it spelling out the name “Reims”. That one word was the instigation for the original local search. Though you are aware that the net has been spread wider thanks to the publicity afforded by the national newspapers. The man is aphasic. Mute. Until the nightmare no one had ever heard his voice. A typical symptom of war neurosis.

‘It’s a sorry case, Commander, but, as I would guess you know from experience –’ he glanced briefly at Joe’s head wound – ‘not at all unusual.’ After the slightest pause he said confidentially, ‘Can’t help noticing that your surgery was not done by the hands of an expert. Hope you don’t mind my mentioning it. If you would like to have someone unpick that, um, attempt and try again I can put you in touch with a friend in Paris who would rise to the challenge.’

Joe smiled his thanks.

The doctor pressed on. ‘Three hundred and fifty thousand Frenchmen, Commander, were declared missing in combat during the four years of war. Blown to bits, vaporized, buried under tons of earth, some just wandered off quietly perhaps. Leaving behind in limbo countless grieving relatives. And these late releases from prisoner-of-war camps have cruelly led their waiting families to nurse a false hope that one day their loved one will be restored to them. People whose dear ones disappear find it genuinely impossible to believe that they will not come marching through the door at any minute. So much grief, so much yearning, and never an end to it.’

‘You touched a nerve, I think, with your appeal to the public?’

Varimont sighed and raised eyebrows to the ceiling. ‘Opened up a hornets’ nest might be more apt,’ he said. ‘Can I say I regret taking such action, I wonder?’

‘Not if you find this poor man a loving home, monsieur,’ said Dorcas. ‘If you can do that, it surely will have been worth the effort. I think it’s a noble and worthwhile thing that you are doing.’

Varimont was startled by the interruption but charmed by the sentiment. Joe was surprised too, by the ease with which Dorcas had spoken in perfectly acceptable French.

‘Mademoiselle has a slight accent of the Midi, I detect?’ said Varimont.

‘My mother is from the south, monsieur. My father is English but we always spend our summers in Provence,’ Dorcas explained.

‘The nightmare,’ Joe picked up hurriedly. ‘Has it been repeated?’

‘Yes. Once more. After the first explosion I did wonder whether to administer a barbiturate. Calm him down. But my second thought was to let it flow on and camp outside his door to catch any recurrence from the start.’

‘And did our man have anything further to add?’

‘Look here – we could go on calling him “our man . . . this poor chap”, we could even refer to him as G27 which is the number on his door, or we could call him – as I do – Thibaud.’

‘Thibaud?’

‘One of the first Counts of Champage. Very popular name hereabouts. Also the name of my great-uncle whom he much resembles.’

‘Perfect,’ said Joe. ‘Tell me what Thibaud had to say for himself.’

‘The same short scenario played and replayed. I was able to write down the words – excuse the spelling!’ He inclined his head to Dorcas, drawing her into the discussion. ‘We do not all have a facility for languages.’ He handed over a sheet from his folder and continued to talk as Joe read it.

‘His dream was accompanied by actions as well as words. He sat up on his bed with a shout of alarm then leapt up and strode about the room, gesticulating madly, quarrelling you’d say, with someone he could see very clearly but who was invisible to me, watching from the door. Then he sank to his knees and screamed out in English: “For God’s sake, man! Don’t do this! Forgive me! Forgive me!” The effect was very disturbing – very . . . theatrical. Does what I’ve written make sense?’

‘Certainly does,’ said Joe. ‘This is an Englishman begging for his life.’

‘With some success,’ said Dorcas thoughtfully, ‘as he’s still with us.’

Varimont was silent for a moment then said hesitantly, ‘Yes, you’d say so. Begging for his life. But, Commander, the odd thing is that his subsequent actions belied the words. He pleaded for mercy with those words, in perfect English as far as I am any judge, but then he acted out a quite extraordinary scene.’

The doctor got to his feet and moved to the centre of the room. The short, fastidious, suited figure should have produced the comical effect of a Charlie Chaplin movie as he launched into his mime but Joe and Dorcas watched in growing horror as the meaning of his gestures became clear.

Eyes rolling in a pantomime of rage, Varimont lifted his right foot and kicked out viciously at something (or someone) unseen three feet above the ground. With a snarl, he reached across his body and drew a sword from its scabbard with his right hand, then, holding it up in front of his face with a two-handed grip on the hilt in a hideous semblance of a priestly gesture, he plunged it downwards again and again.

Chapter Six

As they made their way along darkening corridors, following the fast-moving figure of the doctor, Joe was aware of Dorcas scurrying along at his heels, staying much closer than she would normally have done. The architecture would have detained him in other circumstances, its massive Gothic arches and stone-flagged corridors demanding attention. An ancient monastic building of some sort, he would have guessed, which, by being incorporated at a later date into the structure of the town’s defences, seemed to have survived the bombardment. Though not entirely unscathed. Distantly, he heard the hammering and shouting of a building team at work on repairs and found he was reassured by the sounds of ordinary life going on in this disconcerting place.

Varimont turned a corner and walked down a narrower corridor, pausing finally in sepulchral gloom in front of a stout oak door. Before he could insert his key in the lock Joe commented: ‘Formidable defences. You must reassure me, Varimont, that your Thibaud presents no danger to visitors.’

‘Oh, none at all. These precautions are for his protection. Be reassured, Commander . . . mademoiselle. When he is not suffering a nightmare, he is calm itself. He sits, sometimes stands, looking into an internal distance. He has a slight reaction to some of his visitors. Some he obviously likes and he expresses this by reaching out to touch their arm, very briefly. Do not be alarmed should he do this, mademoiselle. It is a sign perhaps of his returning humanity.’

‘What does he do if he takes a dislike to someone?’ Dorcas thought it prudent to ask.

‘Rather embarrassing, I’m afraid! He climbs into his bed, pulls the blanket over his head and goes to sleep. Come and meet him.’

The tall slender man was sitting on his bed, under the single window, hunched and quiet. Not presented in hospital pyjamas but duly ‘spruced up’, Joe thought, in a white shirt and pressed trousers. The late afternoon sun caught his head, lighting hair that must once have been blond but was now streaked with grey. He was facing away from them and made no response to their entry or Varimont’s cheerful bellow: ‘Hello there, Thibaud old chap! And how are you doing today? Look here – I’ve brought you some visitors.’

There were chairs in the sparsely furnished room but they didn’t sit. There were brightly coloured posters on the grey walls but the visitors paid no more attention to the scenes of the Châteaux of the Loire than did the occupant of the room. They trooped in and stood awkwardly in front of the patient in a line watching him. Joe had once had to escort a terrified young lady from the cinema, passing in front of a row of people absorbed by the last reel of The Phantom of the Opera. Their faces had shown much the same expression as the one he was now studying with attention. The man’s focus was elsewhere and someone passing through his field of vision was a momentary annoyance, no more. The doctor chattered on, behaving as though his patient perfectly understood him. In the middle of a sentence and out of joint with the doctor’s speech, the man suddenly reached out and stroked his arm twice. At once, Varimont responded with the same gesture. Treating this as the establishment of some kind of communication, he drew Joe forward and introduced him.

Thibaud stared through him, his startling blue eyes expressionless, and made no movement. He must at one time have been an exceptionally handsome man, Joe thought. Even the distortion of the jaw, the pallor and the thinness of the flesh could not quite quench an impression of nobility. Joe spoke a few hearty and meaningless sentences and then floundered, running into the quicksand of indifference. Picking up Joe’s hesitation, Varimont then introduced Dorcas.

To both men’s surprise, she stepped forward without hesitating to stand directly in front of him. She made no attempt to speak. She put out a hand and gently stroked his cheek in greeting. Then she reached into her pocket and produced a rose-pink biscuit, one of the biscuits they bake in Reims to nibble with their champagne, Joe noticed. She must have brought it with her from the cake shop, he thought, as there had been no such confection on offer in the director’s office.

They watched as she snapped it in two, releasing a seductive scent of vanilla and a cloud of icing-sugar, and, murmuring, offered half to Thibaud. Joe felt Varimont, standing close by him, tense as his patient turned his head slightly. He allowed her to open his hand and then close it again over the biscuit. Dorcas carefully moved his hand towards his mouth and he began to eat. Having swallowed the first half, he opened his hand and stretched it out. Dorcas gave him the second half and he crunched his way through that too, to her evident satisfaction. When he’d finished, she tenderly whisked a crumb from his chin, crooning to him in a language Joe had not heard before.

And then Joe heard the doctor gasp in surprise. Thibaud turned to her and looked at her as though he saw her at last and he smiled. A smile of utter sweetness and childlike pleasure. And, swallowing his emotion, Joe acknowledged that of the many smiles that would be directed at Dorcas in the coming years, this was the one above all she would remember. A hand came out again, hesitantly, and reached for her shiny black head. He stroked her hair gently twice.

Standing once again outside Thibaud’s room, Joe detained the director before he could lock the door. ‘A moment, sir. That was all very interesting and involving but in no way does our encounter begin to address the problem of your patient’s nationality. I wonder, would you permit me . . .?’

He outlined his plan and the director nodded in agreement. ‘Can’t do any harm and may tell us something. Carry on, Commander.’

Joe opened the door again and checked that the man had, as expected, settled back into his slumped posture, sideways on the bed, face turned away from the door.

In a loud and convincing rendering of an English sergeant major’s voice, he barked out an order.

‘Atte-e-e-nSHUN! On your feet, laddie! Stand by your bed!’ More parade ground commands followed and each was received blankly, with not the slightest twitch of a muscle. Joe went to stand directly in front of him and snapped off a smart salute. ‘Reporting for duty, SIR!’ This time the voice was that of an officer. Impossible for a trained soldier of any rank not to offer the reciprocal salute.

Not one joint of one finger moved in response. Joe looked keenly at the man’s features, awake to the slightest shifting expression.

And, finally, Joe’s efforts were rewarded. At last the face began to twitch. His nostrils flared. His upper lip trembled. His mouth opened. Thibaud gave a wide yawn, collapsed on to his bed and pulled the blanket over his head.

Chapter Seven

Joe waited until he was navigating his course with certainty back across the city before he spoke to Dorcas.

‘So – the doctor’s efforts “will have been worth it” eh? And where, pray, did you learn to juggle the future perfect tense with such confidence, miss?’

He was aware that his question sounded ponderous but he was keen to hear her answer.

She left a silence just long enough to reprove him for his condescension. ‘Well, it could have been – if I’m allowed to use a conditional perfect without incurring disapproval – in the stables of the Vicomte de Montcalme last year. Indeed, I do remember now that it was.’

‘Oooh! Hoity-toity! If you’re going to talk to me like an offended duchess – or worse, her lady’s maid – I’m going to throw you out on to the cobbles right now. Are you going to elaborate on that throwaway remark?’

‘I don’t know where you get your information about me but you must have noticed that my father is a gentleman. He may well be a painter and an English eccentric but I can tell you that these qualities make him very acceptable to aristocratic or rich people who live in the south. He can paint in whatever daubist style is fashionable but what you may not know is that he’s a jolly good portrait painter in a traditional way. His productions are “lively and perceptive”, people say – and I’d add, more importantly, flattering. Last summer he was painting the Vicomte de Montcalme and I used to go along with him and play . . . ride,’ she corrected herself hastily, ‘with the Vicomte’s children. Two sons and a daughter. The oldest boy, Félicien, was my special friend. He’ll be seventeen now. I’m quite good at copying accents, which is a help. Orlando’s been summoned back again to do an equestrian portrait of the Vicomtesse. I can’t wait to see them all again!’

Was all this nonsense true? He had no idea. Ought he to have been annoyed by her sharp tone, lacking the deference due from one of her age to a well-meaning adult and amounting, in fact, to a set-down? Joe smiled. Probably. But pulling rank and demanding respect were not his style. There were other ways.

‘I see. But I still can’t imagine the circumstances,’ he said innocently, ‘that would precipitate the use of complex tenses in a stable. I find horses respond best to a simple imperative.’

Dorcas smiled slightly. ‘“In a year’s time you will have forgotten me.”’ She sighed a lingering sigh, remembering.

‘Talking horses? Whatever next!’

After a startled moment she burst out laughing and he felt it wise to change the subject. ‘Tell me, child – whatever prompted you to treat our friend Thibaud in the way you did?’

‘He reminded me of a boy in our village who’s blind. I know the doctor said all his senses are unimpaired but there was something about his unseeing expression . . . I did what I normally do when I greet Robin.’

‘And do you take Robin biscuits?’

‘When I have them to offer, yes. I take them from Granny’s Chinese jar. Reid always tells me when he’s just refilled it. I was thinking that if this man is really from this area he might respond to a prompting from one of his other senses. Worth a try. A smell associated with his childhood might awaken some memories and, I’d guess, every child born in Champagne was familiar with those pink biscuits. It seemed to work.’

‘It certainly did. I think you achieved more in two minutes than the medical profession in as many years.’

‘I was longing to ask, but I couldn’t get a word in edgewise – do you know if they’ve tried hypnotism?’

‘What do you know about hypnotism, Dorcas?’

‘There’s a chapter in my book . . .’ She held it towards him and a swift glance revealed it to be The Wounded Mind by Lt. Col. M.W. Easterby MD. ‘Aunt Lydia whipped it from a shelf just before we left. She’s done a lot of voluntary work on the wards at St Martin’s, did you know that? She thought it might help you out. It’s only just been published. The most intriguing thing – I’ve marked the page for you – is the story of a shell-shocked soldier who had lost the power of speech. He began eventually to speak again and he talked in the London accent of the nurses and orderlies who tended him, but under hypnosis he suddenly astonished everyone by reliving his wartime experiences in a northern accent. Another patient recognized it as Wearside – you know, from around the River Wear. They tracked him down. He was a Northumberland Fusilier who’d gone missing on the Aisne. But the minute he came out of hypnosis he lost his Geordie accent and became a Londoner again. I wonder why the doctor’s not hypnotized Thibaud?’

‘It’s not a popular technique in France, I believe. But it’s a suggestion worth putting if we see him again.’

‘Were you able to form an impression of Thibaud’s nationality? Is he English, do you think?’

‘Not proven, I’d say.’

‘But he spoke in English. We’ve seen the doctor’s record.’

‘Yes. But I haven’t heard him speak myself. I don’t know the doctor. I liked him and I think I’d grow to admire him as I got to know him but I take no stranger’s evidence without checking, especially witnesses who are closely involved and may be pursuing an agenda of which I’m unaware. I’ve decided, if you don’t mind, Dorcas, to take this problem further. A day more of research in Reims, perhaps two, before we go off to the château.’

‘Are you always as pernickety as this, Joe?’

‘Yes. It drives the men mad. I check and recheck and I make them do the same thing.’

Dorcas pulled down the corners of her mouth. ‘I thought I was coming on holiday with Mr Holmes – all flash and flare, inspiration and dramatic deduction – and what I find I’ve got is Inspector Lestrade.’

Joe grinned. ‘The world can get along without Holmes, I suspect, but it can’t do without its Lestrades.’

‘But Thibaud looks English,’ Dorcas persisted.

‘Looks are not a reliable indicator. Quite a few French from the north have Scandinavian blood like the English and fair or red hair is not uncommon. Like us, they were invaded by waves of Norsemen. Followed by English from the west, Ottoman Turks from the south and Prussians from the east.’

Dorcas was looking about her as they threaded their way back to the centre. ‘The poor French! They’ve been invaded so many times. It’s a wonder they stay French. But they do. Look at those clapboard houses, Joe.’ She pointed to a row of wooden buildings hastily erected amongst the rubble of an ancient market place. ‘You could imagine a shanty town in the Californian gold rush but then you see the beautiful lettering on the shop-fronts, the net curtains, the shining paintwork and the neat piles of produce and you know you couldn’t be anywhere but in France.’

‘They came up from their cellars, rolled up their sleeves and just got on with it,’ said Joe. ‘And all the way through that misery they kept saying the same thing: “On les aura!” – “We’ll get ’em!” And in the end, they did,’ he said sentimentally. ‘But at what a cost!’

‘And so many people paid the bill,’ said Dorcas quietly.

Joe stared in dismay at the blackened stumps on either side of the great doors on the west façade of the cathedral and felt foolish.

‘It’s gone! Of course . . . smashed to pieces by long range artillery like the rest of the statues. I had thought that here on the western side they might have escaped. These portals were crowded with them . . . saints and angels. The loveliest of medieval sculptures and all very natural, quite unlike the stylized, elongated ones at Chartres. They used to be there.’ He waved a hand. ‘Standing about. You’d have said a cocktail party was going on. And there,’ he pointed above his head, ‘is where you’d have found your host – the smiling angel.’

‘There’s work going on – listen!’ said Dorcas. ‘It’s bound to take time. It makes a lot of sense to rebuild the houses and shops before the churches. I’ll have to come back in a few years from now if I want to see this famous angel.’

Joe shook his head. ‘Impossible to recreate, I’d say. I think, sadly, I’ve looked my last on him.’

‘Oh, don’t be so sure of that,’ said a jovial voice behind them and they turned to see a figure from the Middle Ages watching them. A miller was Joe’s first impression. Surely not? He wore a miller’s hat, white with dust, and an equally dusty smock of holland fabric down to his knees. Plaster-caked trousers were secured with string at the bottom and his feet were shod with clogs. Above a grey-streaked beard, sharp, kindly eyes twinkled at them through a pince-nez.

‘Come with me and I’ll show you a wonder! This way, young lady, over that plank and mind where you put your feet.’

Intrigued, they followed their jaunty guide through a stonemason’s yard and into the shell-damaged but serviceable shelter of an outbuilding which might at one time have been a chapel but was now a workshop. Joe was enchanted by the medieval scene being played out all around them, a reassuring blend of bustle and order. Men looked up from their chipping to greet them and to smile warmly at Dorcas. Their work reclaimed their attention at once and claimed Joe’s attention also. Figures from the façades and ledges of the cathedral were being recarved. The fine-grained limestone of the region was being used for repair or complete reconstruction and by hands which were the equal in skill, it seemed, of their ancestors.

‘Over here!’ They followed their guide, whom Joe guessed to be a master builder, judging by the signs of recognition he was receiving from his crew as he passed. ‘There he is. The gentleman you were looking for, young lady.’

He waved an introductory hand as Dorcas stood wondering, a tiny figure, in front of the seven-foot-high angel. A perfect, gleaming new figure. Beneficent and urbane, he beamed his remembered welcome.

‘But how? Can it be . . .?’ Joe murmured.

‘Not the original unfortunately. No. That was shattered beyond repair. But –’ he held up a finger for emphasis – ‘the Monuments Museum had, years ago, had the forethought to have a cast made and it was preserved in Paris. I have replicated the angel using the cast as a guide for my carving.’

‘What a beautiful result!’ said Joe. ‘Worth every effort and a witness for evermore of your talent, monsieur.’ His admiration compelled an old-fashioned but spontaneous bow.

The sculptor beamed in recognition of the compliment.

‘And when may we see him back in his rightful place?’

‘I fear this will be some time in the future. Money has been short. What the town has it spends on rehousing its inhabitants.’ He smiled. ‘You’d say every architect in France is busy in Reims and all trying to express themselves in the new style.’

‘Art deco, you mean?’ said Joe.

‘Is that what you’d call it?’ said the sculptor with gentle irony. ‘Not sure about “deco” . . . or “art” for that matter. But we’ll see. I shall have to try to get used to it. Repairs to the damaged fabric have been going on here at Notre Dame though not as fast as some of us would like. But with the injection of a very large sum of American dollars and some English pounds, work – as you can hear – goes on apace. Soon we may have a façade on which to mount him. Well, there you are. I hope he does not disappoint the young lady.’

‘I think he’s the most wonderful man I’ve ever seen! Don’t you think so, Joe?’

‘Always have,’ said Joe.

They said farewell to their guide and made their way back out into the morning sunshine.

‘Two special smiles in as many days,’ said Joe. ‘Any similarity?’

‘Hardly any,’ said Dorcas. ‘Thibaud’s smile was sweet but it was just a reaction. There was no thought behind it. It didn’t really reach his eyes, did it? The angel was all bright intelligence and good humour. His brain was creating the smile. I really think Thibaud’s brain is mostly dead or frozen up somehow. But I’ll tell you this, Joe – if ever our forgotten soldier were to come back to the world again and if he were to smile . . . good heavens! . . . it would be a smile worth waiting for.’

‘Are we going back to the hospital?’ Dorcas wanted to know as they regained the car.

‘Ah, no,’ said Joe. ‘I thought I’d make a start on interviewing one or two of the claimants. With Bonnefoye’s introduction and signed permission in my pocket I think they’ll agree to see me. Though I rather thought I’d start by going off at a tangent. One of the names on that list is a bit of a dark horse and I’d like to take a surreptitious look at its teeth before I begin anything so formal as an interview. My first call is at a house a street or two away and there is no way in the world I will agree to your accompanying me there. I’m going to park the car a couple of doors down and lock you in with your book while I go in.’

‘Are you seeing one of the claimants?’

‘No. I’m paying an unscheduled visit to someone who may be able to shed light on one of them. A past employer, if you like, with . . . um . . . commercial premises in the rue de la Magdeleine. The lady may be able to furnish a reference and background information.’

Dorcas’s look of puzzlement cleared. ‘Oh, you’re off to a brothel! On the trail of Mademoiselle Desforges.’ She nodded wisely. ‘That’ll be the Rêves de l’Orient. Everyone’s heard about that! It has quite a reputation in tourist circles. Well, don’t get carried away by your research. I don’t want to have to tell Aunt Lydia you parked me outside a Reims house of ill-repute for an hour while you visited. Oh – and I won’t be locked in. Suppose the car caught fire? They do, you know! Look – park the car here,’ she said as they passed along an elegant shop-lined street. ‘There’s things for me to look at. I can see the new Galeries Lafayette. You can walk from here. Leave me the keys and I promise I’ll be here safe and sound when you get back.’

She consulted her watch in a marked manner.

‘If she tells me to “run along now” I shall put her on the first train to Nice with a label round her neck,’ Joe vowed silently.

He strode along the pavement of the rue de la Magdeleine checking the blue enamelled numbers of the refurbished town houses, a run of elegant façades. Had he got the right street? And there it was at the end, set a little way back and looking very proper with its newly painted front door and fresh draperies at the windows. He avoided turning in through the wrought-iron gate and strolled on around the corner. A second entrance at the side of the house and giving on to a street leading towards the river showed signs of use. The iron handrail which led up to the door was worn to a ribbon slenderness, the steps slightly dipped towards the centre. He was quite certain that, in their discreet French way of going on, there would be an even more reticent back door if he were to pursue his exploration. As he lifted the knocker and rapped he thought he could well be visiting his doctor or his dentist. Only the brass plate was lacking.

The door was opened at once by a maid in dark dress and white cap. She took his hat and whisked ahead of him down the tiled hall, calling to him to take care – the floor was just washed and not yet dry. She showed him into a parlour overlooking the street. Joe looked around him. The furnishings were sumptuous and very new and all were imported from the East. A small jungle of large-leafed plants appeared to have broken out.

‘Do sit down, monsieur. Madame will be with you directly,’ the girl said sweetly and left him deciding what to do with himself.

The air was stale with the scent of last night’s Havana cigars, last night’s Soir d’Été perfume too, both beginning to lose the battle with the not unpleasant smell of freshly laid Wilton carpet and beeswax polish. A silk-covered divan which appeared to be the principal seating was piled high with cushions in raging shades of red and purple and was disconcertingly low. He did not wish to be discovered lolling. Nor did he wish to stand about in a menacing way. His eye lit on two Louis XV chairs, one on either side of the door, and he firmly carried them over to the window and set them facing each other. He’d carry out this interview knee to knee, eye to eye. A moment’s study of the window-locking arrangements, never simple in France, was productive; in six moves he had managed to raise the window a foot and stood by it breathing in the fresh morning air.