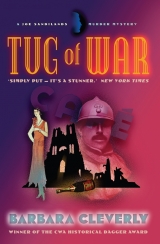

Текст книги "Tug of War"

Автор книги: Barbara Cleverly

Жанр:

Классические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

‘Number four. Ah . . . Now I see why I’m here and about to ruin my first holiday in three years!’ Joe cocked an amused eyebrow at the Brigadier. ‘Madame Clovis Houdart. Of the champagne house near Epernay The invalid could be her husband, Clovis, posted missing in 1917. Do you wish, at this point, to declare an interest, Sir Douglas?’

‘Well, of course!’ He rapped sharply on the desk. ‘But an interest in finding out the truth! You must hear, Sandilands, the facts of the matter . . . be aware of the pressures and expectations then you won’t fall foul of them. I was approached by my friend, Charles-Auguste, when he heard of the involvement of the British authorities. He appeals to me to do what I can to ensure that the widow’s claim is rejected. Proved false. He is quite certain that the man in question is not his cousin. And he is deeply suspicious of the widow’s motivation in all this. Aline. Her name’s Aline. It’s no secret that the two in-laws do not get on well but more than that I can’t tell you. They’re perfectly polite to each other in their French way but you never can tell what’s bubbling under the surface, can you? Awkward, what!’

‘Sir, it occurs to me that we have the same theme running through each of these claims. And I don’t refer to the affection they may or may not have for a dear and supposed departed one.’

‘Go on.’

‘A very prosaic and unromantic but deeply compelling motive. And particularly so in these hard times in France. Money, sir. I fear each of these claims could be based on financial gain.’

‘What an unworthy thought! Had the same one myself. Mm . . . yes . . . been researching this. Save you some time. If he is ever identified to the authorities’ satisfaction, the man will, of course, even though he’s out of his head and unaware of anything, be qualified to receive a very generous allowance from the state. A sort of war pension, calculated from the time of his vanishing to the present day and beyond. Froggies are quite a bit more open-handed than we are when it comes to paying for damages. His family, whoever they are proved to be, can count on receiving – shall we say – eight years’ back pay. A fortune to some of the names on that list.’

‘Park the poor fellow in a rocking chair in the corner and they can go on drawing his pension as long as they can keep him alive,’ said Joe. ‘I would expect he qualifies for a disability allowance? But your friend Houdart? Some other financial advantage there, surely, I would guess? If the widow’s claim were to be upheld, “Clovis” would be restored to the family estates and Charles-Auguste’s presence would be in question, probably redundant. “Thank you so much, dear cousin, but you may leave now. I will do all that is necessary from now on.” Not confident I could navigate the intricacies of the Gallic laws of inheritance but obviously spanners would be thrown into works with a resounding clang.’

‘In a nutshell. Yes. It may come down to inheritance.’

‘But you mentioned something, sir . . . just now . . . which intrigued me. You say your friend contacted you with his plea for assistance after the police and the British authorities were made aware? We may assume his approach to be subsequent to – and perhaps dependent on – the official representation? I’m wondering why they should be bothering you with this affair at all.’

Redmayne was happy with Joe’s perception and his increasingly obvious involvement with the puzzle. ‘Rem acu tetigisti, Commander. Spot on the problem!’ He leaned back, confident that his investigation was launched. ‘This director of the asylum, you had correctly identified as a good egg. Scientist by training, medical man, student of Charcot and Freud, I understand, not a civilian placeholder. You’re to liaise with him. He’s the target of much sniping from various French government departments for reasons you can probably guess but he has an interesting tale to tell. He got his voice heard largely because the new information he had to offer rather suited them, I’m thinking. But then, I have a very suspicious mind.’

Joe remained silent waiting for the final twist and jerk that would land him firmly in Redmayne’s net.

‘This medic has lavished care and attention on our mystery man, whose case seems to have caught his imagination. He has made copious notes on his condition and tried, by experiment, not electrical shocks – the doc is a humane man, it would seem – to find out the nature and cause of his illness. One night, a week or so ago, he was called by a nurse to the man’s room. The patient was reported to be having a particularly alarming nightmare and crying out in his sleep. Fascinating, of course. Normally completely dumb, perhaps, under the influence of the nightmare, he might well reveal some information? A useful name or two . . . “Odile, mon amour, tu me manques! Maman, ton fils, Robert, te cherche!” Something of that nature.’

‘Yes? And did he make out any words?’

‘He did. Most surprising. And how lucky for us that this director is an educated man. He recognized the language at once. The patient was screaming out a stream of words.

And this is where we find ourselves involved, Sandilands. The words he was screaming were English.’

As Joe paused in the doorway to readjust the bulky file under his arm, Redmayne called out: ‘By the way, Joe . . . a last word of advice. The name “Houdart” . . . know what it means?’

‘No idea, sir. I’ve never heard it before.’

‘No. Most unusual. Charles tells me it’s a very ancient one from two Germanic roots.’ He frowned in an effort to remember. ‘Hild, meaning combat and hard meaning . . . well . . . hard. Hard in combat. Tough fighter. And although Aline wasn’t herself born with that surname – I believe she started out as a de Sailly – she’s certainly grown into it. Oh, and Aline Houdart, you’ll find, is a damned attractive woman.’

The glance he directed at Joe was avuncular, amused. ‘Have a care, my boy!’

Chapter Four

As Joe ran downstairs towards the open door of the breakfast room he glanced at his luggage, set in the hall the evening before ready for an early start. His two suitcases had been joined by one Gladstone bag and a pile of books done up with string.

Cheerful voices and a clatter of dishes warned him that breakfast was well under way and he checked his watch, annoyed to note he had overslept by half an hour. He paused by the door to collect himself and prepare for the good-natured teasing that would greet his late appearance. As he listened he took a furtive step back, startled by what he was hearing.

‘Well, my money’s on this Houdart woman,’ Lydia was saying firmly. ‘Sounds to me like someone who knows what she wants and gets it. She’ll do a deal with the authorities, pull strings . . . pull Joe’s strings too, I shouldn’t wonder! And she’ll have this poor man for her nefarious purposes.’

‘Can’t say I’d mind being had for nefarious purposes by a glamorous champagne widow,’ said Joe’s brother-in-law. ‘She can have her wicked way with me any day. Oh, I don’t know. Let’s add a sporting dash of excitement! Why not? I’ll go for the dark horse . . . Mademoiselle from Armentières . . . what was her name? Pass me that sheet, Dorcas.’ There was a rustle of paper. ‘Mireille, that’s it. Yes, if you’re making a book put a tenner for me on the Tart from Reims.’

‘Marcus!’ Lydia protested automatically. ‘Language! Ladies present!’

‘You’re both wrong,’ said Dorcas. ‘Aunt Lydia – do I still get my weekly pocket money while I’m in France? Good! Then, will you put a shilling for me on the Tellancourt family?’ Raising her voice, she said casually, ‘I’ll pour some coffee for Joe and ring for more. I’m sure I heard him come downstairs just now.’

Joe snapped the catch of one of his cases noisily then entered looking distracted. ‘My file? I say, has anyone seen . . .? Could have sworn I’d left my file with the luggage last night . . . Oh, I see I did . . . There it is between the Cooper’s Oxford and the Patum Peperium . . . Good morning, everyone! Anything interesting in the papers this morning?’

Marcus and Lydia looked at each other and smiled guiltily.

‘Not really,’ said Dorcas. ‘We had to read your rubbish for entertainment. I can see why you didn’t bother to hide it. Hardly confidential. Not a single body on any page. I wonder when you were intending to tell me of the change in our itinerary, Joe? Sounds exciting – though I’m not sure I’m prepared for a weekend living la vie de château. What do you think, Aunt Lydia?’

‘Oh, goodness! Of course! We must pack your best dress – the blue one you said was too fussy . . . so glad we bought it! And you may borrow my pearls . . . Stockings! You’ll need silk stockings. Gloves! We didn’t think of gloves!’

Joe groaned and took the coffee Dorcas was handing him. Fortified, he reached out and gathered in the scattered pages of his file, reprovingly scraped a blob of marmalade from the top sheet and replaced them between the covers.

In frantic but silent communication, Lydia and Dorcas rose to their feet, hastily putting down their napkins. ‘Porridge in the pot, Joe . . . eggs, bacon . . . the usual,’ muttered Lydia. ‘How long have we got?’

‘Half an hour,’ he said. ‘Wheels turning by nine?’

‘Dorcas, scoot along, will you, and find your dress and anything else that comes to mind in view of the change in plans? You’ll need another suitcase – ask Sally to fetch down one of mine. I’ll look out some suitable jewellery and other folderols.’

When Dorcas had charged out of the room Lydia turned to Joe wearing her big-sister’s expression. ‘A word, if you please, Joe.’

He looked at her warily.

‘You may be a senior police officer and a pillar of society, as all would agree, and never think that I’m ungrateful for your offer to escort the child down to the Riviera but -’

‘My offer! Come on, Lydia! I listen for your next pronouncement in the hope of hearing the words “sorry”, “twisting” and “arm” in that order. “Coercion” would be acceptable.’

‘Don’t be pompous! You ought to guess from my circumlocutions that, just for once, I am actually trying hard to choose my words so as not to give offence.’

He looked at his watch, hiding a smile. ‘Twenty-five minutes.’

‘Very well then.’ She hesitated and went on firmly: ‘In England no one will look with anything less than indulgence at an uncle chaperoning his niece down to her father. And that’s all very well. But I’m not so sure of customs and manners in France.’

‘It’s a bit late, isn’t it? To be having such qualms? Pity it didn’t occur to you when I was trying to wriggle out . . . But let me put your mind at rest, Lyd. There’ll be no problems of a social nature. So long as the child remembers to wear her gloves and speak when she’s spoken to, say “yes, uncle” and “no, uncle” at every verse end, I see no problem. People will approve. I’ll be held up as an example from Calais to Cannes of self-sacrificing uncle-hood.’

‘All the same, I do feel myself responsible.’

Joe grinned. ‘You always did, Lydia. It can be infuriating. Look, love, stop fretting. Dorcas always comes out well, you’ve discovered that. She’ll be just fine.’

‘Of course she will! It’s not Dorcas I’m fretting about, you chump! Oh, Marcus! You’ll have to speak to him!’

Left alone, the two men rolled their eyes in affectionate complicity and sank thankfully into a companionable silence, giving their full attention to plates of kidneys and bacon with copies of The Times and the Daily Herald on the side.

‘Stockings?’ Joe looked up, struck by a sudden thought. ‘Hasn’t the child got supplies of socks?’

Marcus seemed to be having difficulty with a piece of toast and coughed behind his napkin. ‘You haven’t noticed, have you, old boy? She’s growing up fast.’

‘Well, of course I’d noticed! She’s put on about two inches in every direction since you had the keeping of her. Good food, regularly offered. Makes a difference.’

‘Exactly A difference. Glad you’re aware. Lydia couldn’t be quite certain that you were. Well, there you are then. I’ll tell her. “Joe’s aware,” I shall say!’

Joe pondered on this for a moment. ‘I say, do I consider myself spoken to?’

‘Can’t imagine you’d want me to elaborate. I will venture to add a word of advice of my own though . . . a thought or two from a man of the world, family man, father of girls and all that: if our perusal of the file is correct, I assume you’ll be taking young Dorcas with you to stay with this family? Yes? Well, you could hardly park her in some hotel in war-torn Reims while you go off by yourself. There’ll be a warm reception and – Lydia noticed – the company of the young son of the house. Dorcas will want to make a good impression. Wouldn’t expect her to come down to dinner in the shorts and sandals she’d packed for the south of France, would you? The whole thing may be a bore and a distraction for you, Joe, but I can tell you, for the girls it’s a romantic interlude. Let them enjoy it and don’t be so stuffy!’

‘And that’s your advice? You hand me the fruits of your years of fathering and it amounts to – “Don’t be stuffy”? Wouldn’t fill a book, would it?’

Marcus gave Joe a long look over the table and spoke in a voice of rough affection. ‘It’s a long way down to Antibes. It will seem twice as long if you antagonize Dorcas.’ And, seeing Joe was about to explode with indignation, ‘Take it easy, old chap. You’re wound up tight as a spring. Can’t help noticing. I’m saying she’s rather like a partly trained little wild creature – think of a ferret . . . Remember Carver Doone?’ he added lugubriously. ‘Lyd’s done her best – so have I – but there’s some way to go yet before we can present her at Court. Or for tea in a Joe Lyons Corner House, come to that.

‘Well, that’s it. I’ve said my piece.’ Marcus sat back, relieved to hear no riposte from Joe. ‘Listen, old man – those buggers at the Yard work you too hard. Lydia and I are always concerned for you, considering the life you lead . . . always mixed up in murder and mayhem of one sort or another. It will be a relief to us to know that for the next three weeks at least you’re not dicing with death.’

Chapter Five

‘Did you lay this on specially, Joe?’

Dorcas, sitting in the passenger seat of the Morris Oxford cabriolet, looked up from her guidebook and stared with disbelief at the scene in the street before them.

‘Certainly didn’t,’ said Joe impatiently. ‘The street’ll be blocked for hours!’ He glanced at his watch. ‘We’ll be late. You’d have thought my opposite number . . . what’s his name? Inspector Bonnefoye, that’s it . . . would have warned me this was happening. He must have known.’

‘I expect he did know,’ said Dorcas easily. ‘You’ll find it’s a dastardly Gallic wheeze to put you in your place and, for the French, your place would always be one step behind and on the wrong foot. It’s manipulation . . . Joe, what are those beasts we’re looking at? What are they doing in the middle of the city and how fast do they go?’

‘Rather splendid, aren’t they? Oxen. White oxen. Eight of them pulling each dray at about a hundred yards per hour and there would appear to be drays as far as I can see until they disappear round the corner of the Avenue. Look, this one’s dedicated to the wool trade and the next is the biscuit-makers’ float. Champagne houses after that . . .’

‘There’s a banner! Reims Magniflque, that’s what we’re seeing.’ She squinted into the distance and read: ‘It’s la grande cavalcade and it’s celebrating the resurgence of the city after the exigencies of the Great War. Well, it’s quite a nuisance but you have to say – well done them!’ She looked around her at the cheering crowds, the marching band, the buildings under reconstruction or already rebuilt and still shining clean. ‘Eight years, Joe, that’s all the time they’ve had to build the city up again from the rubble the German army reduced it to. Look, there’s a picture in my book of the cathedral in flames. September 1914. The Germans were over there,’ she waved an arm vaguely to the north, ‘and they just took pot shots at it with fire bombs. Some scaffolding around the north tower caught alight and the whole building went up in smoke. Many of their own German wounded who’d been sheltering in the nave were burned to death along with the nuns who were nursing them.’

She looked up from her book, face puckering with distress. ‘They’d been here in the city only days before. They’d seen the beauty of the cathedral right there in front of them. How could they retire a few miles off and deliberately destroy it? I can’t understand.’

Joe had no answer. He’d felt her increasing sadness as they’d driven south through remembered battlefields and, in the end, had set aside most of the places he’d intended to see as unsuitable for a sensitive young person. He had not anticipated the force of her reaction to the memorials and had watched, disturbed, as the child had stood in floods of tears in front of the very first one they had visited, patiently going through all the names, insisting on pronouncing each one in her own private ritual, unable to move on until each man had been faithfully acknowledged.

‘Have you never been this way before, Dorcas?’ he’d asked. She reminded him that her father was a pacifist and a conscientious objector who’d spent the war years in Switzerland. They had always travelled through Dieppe and Paris and the war was never referred to. Orlando saw no reason to remind his children of this sorry episode.

In the end Joe had reduced their visits to two places of remembrance. Mons where it had all started and Buzancy, not very distant, where for him it had all finished in that bloody July four months before the end. He’d chosen Buzancy because it represented the combination, at times uneasy, of the allied forces. French, British and American had all fought here. But, above all, he’d chosen it because the small stone monument, a cairn in his eyes, had been hastily built up from material to hand after the battle; it was simple and affecting and bore no heartbreaking lists of the dead. Erected by the 17th French Division in honour of the 15th Scottish, it marked the place on the highest point of the plateau where had fallen the Scottish soldier who had advanced the farthest. A simple two-line inscription said it all, Joe thought:

Here the glorious Thistle of Scotland will flourish forever amid the Roses of France.

Now they’d arrived in Reims, he was determined to put nostalgic thoughts aside. Put out though he was by the hold-up, he was cheered by the sight of so much determined gaiety around them echoing his mood.

‘But look at the town now, Dorcas! It’s almost back together again. A triumph of civilization over barbarism you might say. That’s worth celebrating. Sit back and enjoy the show! And tomorrow I’ll take you to see something really special. Something symbolizing for me and for many others, I know, the spirit of this part of France.’

They paused to clap and cheer as another cart creaked past, overflowing with flowers, fruit and vegetables, the produce of the market gardeners of Cormontreuil.

‘I’ll show you an angel. Not just any old angel. You know . . . holy-looking . . . eyes raised piously to heaven . . . suffering a frightful stomach-ache. This one is smiling. You’ll find him by the great door to the cathedral. He’s smiling at someone at his elbow, caught, you’d say, in the middle of a conversation, or even telling a joke. And I always look for the glass of champagne in his hand. No – it isn’t there, but you can imagine.

‘And the Germans didn’t have it all their own way! In their hurried retreat from the town – they’d been here for four days – some of the troops got left behind. They were carousing and failed to hear the bugle sound. Sixty of them were taken prisoner single-handedly by the innkeeper. There are tales of French derring-do on every street.’

‘How about a spot of English dash on this street?’ Dorcas suggested. ‘Look – there’s a gap between the floats – they’re having problems with that tractor and the policeman who stopped us seems to be rather distracted by the lightly clad young ladies from the Printemps display. Why don’t you . . .?’

Joe had already put his foot down and was surging forward through the gap.

‘Left here and second right,’ shouted Dorcas and, for a moment, Joe was almost glad she was aboard.

Satisfyingly, they arrived at the Inspector’s office a neat five minutes before they were expected and Dorcas had sufficient time to run a comb through her tangled black hair and fasten it back with a red hair ribbon. In short white socks and a red candy-striped dress tied up at the back, English guidebook in hand, she was perfectly acceptable, Joe thought. He introduced her as his niece on her way south to join her father and the young Inspector gave her no more than one brief look, offered her a chair in a corner of his office and politely asked if the young lady spoke French. On impulse, Joe said, ‘Unfortunately not.’ The Inspector was clearly not surprised to hear this admission and remarked with only the slightest touch of condescension how unusual it was to hear French spoken so well by an Anglo-Saxon. Where had the Commander learned his French?

He appeared intrigued to hear of Joe’s involvement in the later stages of the war with Military Intelligence and his months of working as liaison officer with some distinguished French generals. His eye was drawn for a moment to the discreet ribbon of the Legion d’Honneur which Joe had fixed to his jacket as they mounted the stairs. Joe thought Bonnefoye looked too young to have participated in the war but, from his bearing, he judged he might have at some stage undertaken a military formation. He decided to treat him with the clear-cut good manners of a fellow soldier.

They were politely offered refreshment. Tea? Coffee? Joe deferred to Dorcas who, to his annoyance, went through a pantomime of wide-eyed ‘What was that, Uncle Joe?’ and then produced a triumphant: ‘Café. I’d like café, please.’

A tray was sent for and the two men settled to business. Files were produced. Dorcas opened her book.

With a few pointed questions the Inspector satisfied himself that Joe had made himself familiar with the facts of the case and was taking it seriously. Joe, in turn, filled in some gaps in his information and noted down the time of the interview the Frenchman had arranged for that afternoon with the doctor in charge of the case. He obtained further details of the four claimants and the Inspector’s written permission to interview them at the addresses given if he wished. This was handed over with only the slightest of hesitations. A hesitation which was, however, picked up at once by Joe. With a slanting glance of complicity he took the sheet Bonnefoye was handing him, folded it negligently, sighed and tucked it away in his file. He made a phantom tick against an imaginary checklist on the front page of his file and directed his full attention back over the desk again. After a further few minutes of polite sparring, Joe nodded and closed his file, putting his pen away in his pocket.

‘Good. Good,’ he said, smiling. ‘Well, I’m sure I shall be able to supply the help I think you’re seeking.’ He stirred in his seat and raised an eyebrow, catching Dorcas’s attention. ‘Ready, my dear?’ He turned back to Bonnefoye, halfway out of his seat, hand extended. ‘Oh, before we go, perhaps you could just give me a clue as to what the position of the French authorities – the Pensions Ministry, shall we say? – might be in this affair should our poor unfortunate prove to be an Englishman?’

To his surprise, the Inspector put back his head and laughed. ‘I think you know that very well but I will confirm: they will say thank you very much, and post the parcel on to you. Thus saving the department thousands of francs in a country where resources are short! But a positive identification would be most welcome on other grounds. You will be aware of the overheated interest of the press?’

Joe nodded.

‘Naturally, everyone from the Senator downwards is under pressure to resolve the problem. And the claimant families are increasingly a force to be reckoned with as they thread their way through the intricacies of bureaucracy, learning a trick or two as they go. They are showing a determination, a tenacity and a talent for trouble-making which no one could have anticipated. I can tell you – they’re time-consuming, demanding to the point of aggression and they’re becoming a damned nuisance! They’ve found out about each other’s claims and competition’s hotting up. Third battle of the Marne about to explode about our ears?’ The Inspector shuddered delicately.

‘I hear they’re even taking bets on the outcome back in England,’ said Joe sympathetically.

The Inspector’s neat black eyebrows signalled mock horror. ‘Not over here to nobble the favourite . . . fix the odds . . . I hope, Sandilands? Seriously, sir, I must emphasize the folly of becoming too closely involved with any of these individuals.’ He held up a hand to deflect Joe’s instant rebuttal. ‘I do not exaggerate the difficulties. To have survived with their case intact to this point, they must of necessity be determined characters. You must appreciate that. I speak from personal experience when I tell you that they are involving and, each in his or her different way, convincing. And they are spreading their net, gaining public support for their own faction. They seem to have tapped into a seam or a mood of national angst – if I may use a German word – and every Frenchman and woman is passionate to know the outcome. There’s more riding on this than the Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe.’

‘And, of course, the whole world loves a mystery,’ said Joe.

‘True. But the moment it’s discovered that the chap is really François Untel, a deserter from Nulleville, then the brouhaha will die off quickly. Even faster if he proves to be Joe (I beg your pardon!) Bloggs from London. As you say – it’s the mystery that enthrals. The solution rarely proves to be of equal fascination.’

‘Yes. Take your meaning,’ drawled Joe. ‘And what a letdown it would be, were we ever to reveal the identity of Jack the Ripper.’

Bonnefoye smiled. ‘I am heartened to hear that Scotland Yard is finally in possession of it. We were hoping you would show yourselves a little more effective in the pursuit of our own puzzle,’ he said. ‘We will all heave a sigh of relief. We await with interest the outcome of your inspection this afternoon, Commander. Who knows? Perhaps by tomorrow you will be booking an extra passage back over the Channel? And I shall be putting this file away and planning to counter some real crime!’

Joe stood up. ‘Well, let’s remember what Uncle Helmut von Moltke said, shall we? “No plan survives contact with the enemy for more than twenty-four hours.” Oh, I say . . . do you have a place where a chap might . . .?’

‘Of course. Let me show you.’

Bonnefoye led him to the door and pointed down the corridor. Sighing, Dorcas looked at her watch, opened her book again and waited.

‘Well – what did you make of the Inspector?’ Joe asked affably when they settled once again in the car.

‘I liked him,’ she said. ‘Good-looking and he has lovely teeth. I wasn’t happy to see you making such a fool of him. Are you always as devious as this?’

‘What on earth can you mean?’

‘Stop it, Joe! Come off it! I’ve a jolly good mind to tell Aunt Lydia that you’ve set me up as some sort of apprentice Mata Hari. She won’t be pleased! “The child doesn’t speak French” indeed! How could you know he was going to make a phone call the minute you had your back turned?’

‘Did he? Well, I never! I wonder who he rang with such urgency?’

‘Two calls actually. You were gone a very long time. The first was to a superior, judging by his respectful tone.’ Her face lit with mischief. ‘He was passing on his first impressions of the English policeman. I understood most of it . . . dur à cuire . . . would that be flattering? He warned whoever it was at the end of the wire that he should not consider attempting bribery. He judged you unsusceptible to that sort of thing. I was longing to tell him you’re really about as straight as a corkscrew! But, dumbly, I just had to listen to this ill-informed judgement. The second was to the doctor at the mental hospital confirming the appointment and asking him to spruce up the patient and make him look as attractive a proposition as he could.’

‘Spruce him up? Huh! They seem to think I’m going to sign a form or two, pop this man into the back seat and drive him straight back home to Blighty.’

‘Yes, I think so. And if that’s what’s going to happen, you might as well put in for the bribe, don’t you think? I couldn’t hear the doctor’s response but he didn’t seem to like the suggestion. The Inspector was getting exasperated with him.’

‘Always useful to know these things. Look, I think before we check into the hotel, I’ll buy you a hot chocolate. Or a lemonade? Both? There’s a chocolatier over there. And we can pore over the maps and work out my best route to the hospital. I imagine you’d rather stay behind and have a rest? I’ll tell the receptionist to watch out for you and send you up some dinner. I’m sure that’ll be all right.’

‘Joe?’

‘Absolutely not! A mental institution is no place for a young girl. Don’t even think of it!’

‘Not in the least, Commander! Don’t concern yourself. It is nothing but a delight to welcome such a fresh young presence inside these drab walls. Better than a bunch of flowers!’ The director twinkled gallantly at Dorcas and hurried to draw up a chair for her. ‘And may I assure the young lady that she will witness no scenes of a distressing nature during your visit?’

From the reports, Joe had pictured a dour, earnest and competent clinician in a long white coat. He was surprised and intrigued by the figure who had come himself to the main door of the hospital to greet them. Impeccably dressed in a grey suit and formal stiff collar, Patrice Varimont was short and bustling, radiating energy and good humour. His dark hair was parted precisely in the centre and controlled by a touch of pomade, his cravat was pinned down by a discreet regimental tie-pin. Joe noticed that all the workers they passed on their way up to his office, medical and civilian, quickened their pace on catching sight of him and murmured a respectful salute before hurrying on.