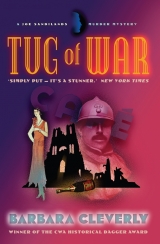

Текст книги "Tug of War"

Автор книги: Barbara Cleverly

Жанр:

Классические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

Chapter Two

The War Office, London, August 1926

‘I’m sorry, sir. Truly. Of course, I would have liked to oblige but . . . no . . . the answer has to be – no. I’m afraid it simply can’t be done. I have to plead a prior engagement.’

Joe Sandilands stirred uncomfortably in his seat. He was unused to refusing to fall in at once with a requirement, order, wish or whim from a superior officer. And Brigadier Sir Douglas Redmayne was a very superior officer. No one ever got into the habit of denying Sir Douglas anything. A second opportunity never presented itself. The Brigadier seemed equally surprised and discomfited by the feeble rejection. He bristled at Joe across the breadth of mahogany desk, bushy eyebrows gathering in attack with moustache coming up in support.

His hand reached out and he pressed a buzzer.

Joe rose to his feet and turned to face the door. He braced himself for the entry of a matched pair of the heavy brigade he’d caught sight of standing on duty in the corridors of the War Office on his way up to the fifth floor and prepared himself for the ceremony of ejection from the premises. It would be embarrassing, of course, but not entirely unwelcome. In fact he’d need an escort to find his way out of this imposing baroque building with its two and a half miles of corridor. Everything around him from the shining white Portland stone cladding on the pillared exterior to the heavy gold and ivory desk furniture was designed to overawe.

To Joe’s surprise the two expected thugs made no appearance; the door was opened by one small female secretary.

‘This would seem to be as good a moment as any, Miss Thwaite,’ said the Brigadier with a nod. ‘If you will oblige?’

Miss Thwaite favoured them both with an understanding smile and disappeared.

‘Resume your seat and hear me out, Commander.’ Redmayne smiled and selected another card from his strong hand: ‘Perhaps I should have mentioned that I am seeing you with the knowledge and permission – encouragement even – of your Commissioner. From whom I continue to hear good things. Liaison between our departments, I’m sure you’ll agree, has . . .’ Into the slight pause, Joe knew he was meant to slide the thought: ‘until this moment’. ‘. . . been cordial and effective.’

Joe sat down again, eyeing Redmayne with what he hoped was an expression at once undaunted but unchallenging. The officer was, he reckoned, ten years older than himself, probably in his early forties, lean, active and professional. His title was as impressive as his appearance: ‘Imperial General Staff, i/c Directorate of Military Operations and Intelligence’. As baroque as the building, Joe reckoned. He’d always known it as ‘Mil Intel’. A survivor of the war, Redmayne had worked his way to his present eminence, it was said, thanks to more than his fair share of luck. But Joe would have added: intelligence and a speedily acquired understanding whilst under fire of the changing nature of warfare. And, if the stories were to be believed, a strong streak of ruthlessness had stiffened the blend.

‘Now, be so kind as to hear me out, old chap!’ said Redmayne into the silence, trying for a tone of bonhomie. ‘I’m perfectly aware of your travel arrangements.’ He poked at and then straightened a folder in front of him, a folder containing as the top sheet, Joe was sure, the outline of his holiday plans. ‘Nevil was kind enough to send over your file before he left for Exmoor.’

Out of courtesy and custom Joe had sketched out his itinerary beginning with departure early tomorrow morning from his sister’s house in Surrey where he would pick up a package and make for the Channel port, and going on at a speed dictated by the performance of his car and the state of the roads all the way down to the south of France. He’d even given estimated dates of arrival at hotels along his route. But his plans further than Antibes he had not confided for the simple reason that he had none. He was looking forward to a blissful two weeks of wandering around Provence before starting for home again.

‘I see you’ve elected to take the Dover crossing to Calais and then on down through the battlefields, fetching up at Reims.’ The Brigadier looked at him with speculation. ‘Many chaps would have gone Newhaven-Dieppe to Paris and avoided all that.’

‘Avoiding “all that” is not something I would ever want to do,’ said Joe quietly. ‘I have respects to pay. Memories to keep bright.’ In embarrassment he added, ‘And you have to admire what the French and the Belgians are doing by way of transforming all those hellish bone-yards into memorials and cemeteries. There are some quite splendid monuments designed by Lutyens I should like to take a look at . . .’

‘Good. Good. Well, I see I’m not sending you out of your way then. Not at all. You’ll be passing through Reims. Centre of the once glorious champagne trade. All I’m asking you to do is break your journey at this address instead of staying at a hotel. Here you are.’

He passed over the desk two small white cards. Joe looked first at the visiting card and read in curlicued, florid French lettering: Charles-Auguste Houdart, Château de Houdart, Reims, Champagne. The second card was a merchant’s copy of a wine label. A spare architectural sketch of a small château nestling between beech trees showed ordered lines of vines marching up a slope behind and disappearing into the distance. Across the top was printed the name of the champagne house, which appeared to be Houdart Veuve, Fils et Cie.

‘Your wine merchant, sir?’

‘Yes, that, but also my friend. Charles-Auguste. Splendid fellow. You’ll like him.’

‘And is your friend Charles-Auguste the son of this house?’ Joe asked, intrigued despite his unwillingness to show the least co-operation with this scheme to divert him from his plans.

‘No, he isn’t. I suppose you could say he’s billed as Cie – la Compagnie. He runs it after all. On behalf of the aforementioned Widow and Son. Ever heard of this brand, Sandilands? No. Can’t say I’m surprised. It’s a very small house . . . not one of the grandes marques like, oh, Moët et Chandon, Ayala, Bollinger, Veuve Clicquot. But to a connoisseur the name Houdart speaks volumes. Interesting history. Especially recent history. You’ll remember the two battles of the Marne damn nearly scoured this country out of existence? Some of the larger estates are only just beginning to get back to pre-war production levels but this little château managed to survive practically unscathed. And all in spite of losing the owner and moving force of the enterprise to the war. Clovis. His name was Clovis. He rode off to war, disappeared and was posted “missing, presumed dead” in 1917. He left a widow and a seven-year-old son behind. But quite a widow as it turned out! Gallant, in the tradition of Champagne widows. Nothing loath, she rolled up her sleeves, kicked off her sandals and trod the grapes, so to speak, alongside whoever she could get hold of to work the estate. And it paid off, it would seem. Nothing prospered, of course, in that dreadful four years but it survived. And now it’s prospering like anything!’

‘I’ve identified the Veuve, and the Fils – her son – must be about sixteen now? But where does your friend, who I see bears the family name, come into this?’ Joe’s interest was polite and professional but no more than that.

‘Charles-Auguste. He’s a cousin of the chap who disappeared on the battlefield. When it was clear that Clovis had been lost he came up from Provence where he had a small winery himself and took the reins from the doubtless weary hands of the widow. With huge success. But you shall judge for yourself! Thank you, Miss Thwaite!’ he shouted cheerily to his secretary who entered bearing a tray set with champagne glasses and a bottle in a silver ice bucket.

Joe’s mouth tightened. All this careful stage-setting boded ill for him. He scowled critically at the wine he was offered and listened to Redmayne’s hearty toast: ‘To the Widow!’

‘To all widows,’ Joe murmured in response. ‘God bless them.’

He sipped the wine and sipped again with pleasure. It was as good a champagne as he had ever tasted and he said as much. Redmayne appeared pleased. ‘This is the 1921 vintage,’ he said. ‘Only just been released. Reports are that last year’s will be even better. While you’re down there, Sandilands, I want you to be sure to register an order for a certain quantity to be shipped to me when the moment comes. Charles-Auguste will advise you. Very much to my taste. The bouquet is excellent – don’t you think so? People are so intrigued by the bubbles they often forget to appreciate it, you know. And the degree of dryness is spot on. They get it right. What do you make of the colour?’

Well, if this was the game, Joe could hold his end up. Hiding a smile, he raised his glass to the light and squinted at it. ‘Rather deeper than one is accustomed to – a brilliant intense gold.’ He swirled the wine gently, put his nose to the glass and sniffed briefly ‘And a bouquet to match. Spices, would you say? Vanilla certainly but . . . cardamom? Yes, a whisper of cardamom . . . and fruit . . . Something here from my childhood . . . got it – quinces! Quinces cooking with apples under a buttery pastry crust.’

Redmayne stared and blinked and Joe wondered if he’d overdone it but the only response was a dry: ‘Indeed? Mmm . . . And I detect a touch of Proust, I think.’

They drank companionably together, Redmayne talking knowledgeably of blending, first and second pressings, remuage, dégorgement, while Joe waited for the blow to fall.

‘More wine, Sandilands?’

‘Thank you. Would this be a good moment, sir,’ he said genially, ‘to tell me why you’ve summoned me here? My detective skills lead me to suppose you wouldn’t have called in a Scotland Yard Commander to hand him a shopping list for champagne. I’m wondering what service, exactly, Monsieur Houdart would be expecting me to perform – were I to accept this chalice which I suspect will turn out to be heavily laced with some poison or other?’

Joe held out his glass.

Redmayne smiled as he poured. ‘As a matter of fact there is something you could do for him. Just a small favour. Army involvement, of course. French, possibly British. This thing landed on my desk, diverted from the Department of the Adjutant General, the Directorate of Prisoners of War and Personal Services – if you can believe! – but mainly it’s the French police you would be helping. The request for assistance came, in fact, from them. From the very top. Oh, yes. Police Judiciaire involved . . . and rather puzzled to be involved, I gather. At all events, they handed it swiftly to Interpol and you’ll be only too aware, after that last lot, that we owe them a considerable favour. Your mob owe them a considerable favour. The least we could do, I thought, when they approached me, was to send someone along to liaise with them. Interesting case. You’ll be intrigued.’

Not quite at ease with his presentation, Redmayne got up and strode to the window, hands behind his back. He pushed up a pane, the better to catch the bugle call coming up from Horseguards below, and looked out with satisfaction over to the crowding green canopy of trees in St James’s Park.

He cleared his throat. ‘Of course, it’s the press involvement that stirred the whole thing up. And now the country’s in a frenzy. Nothing like a mysterious death and a grieving widow to get the Froggies going! The whole population dashes out in its slippers every morning to buy a paper and read the latest instalment of the drama. Haven’t seen anything like it since the death of Little Nell hit the news-stands.’

Joe had, as a child, ridden without permission a horse which, he had very quickly realized, was out of his control and heading for the hills. The same sick feeling was growing as Redmayne talked.

‘Sir! A moment!’ He attempted a tug on the reins. ‘Police? Interpol? Mysterious death? This doesn’t sound like a matter I can attend to between sips of champagne and polite conversation. Whilst flighting south for the summer. There’s an officer in my department, ex-guardsman – Ralph Cottingham. I know he would be delighted to get away for a week or two.’

Joe had overstepped the mark.

‘Thank you for the suggestion, Commander,’ came the curt reply. Redmayne turned and glowered. ‘Cottingham’s name came up, of course. I always choose the best man for the job and in this case, with your wartime experience in Military Intelligence and your knowledge of the language, you are he.’

His words had a finality which depressed Joe but then the Brigadier unbent and gave a tight smile. ‘And I don’t forget that you were right there – on the spot as it were. Caught up in the battle of the Marne, weren’t you? Your local knowledge may come in handy. And, better yet – travelling under no one’s auspices but your own, your section will avoid any belly-aching from accounts in the matter of extra departmental expense. We’re all accountable these days to pen-pushing pipsqueaks of one sort or another. It irritates me to have to take these petty restrictions into consideration and I expect it’s much the same with you but – this way neither Nevil nor I will be expected to foot the bill. Some might consider the offer of a weekend’s hospitality at a château a more than adequate quid pro quo.’

‘And so it would be, sir, if I were free to accept it.’ Joe’s voice had an edge of desperation. ‘But, you see, there’s a . . . an . . . impediment. For the outward leg of my journey, at least, I am not a free agent.’

The Brigadier returned to his desk and poked again at the file. ‘Something you haven’t declared?’

‘Not something, sir. Someone. I shall not be alone. For the journey down to Antibes I shall be travelling with a female companion.’

Chapter Three

A questioning flick of Redmayne’s eye towards the file betrayed, to Joe’s satisfaction, that the official records evidently did not contain full coverage of his private life.

‘A lady, you say?’

‘I think I said female, sir. Not sure the word lady would be appropriate.’

Redmayne was, for a moment, disconcerted. But only for a moment. His expression adjusted itself into one conveying comprehension and collusion. ‘Look here – is the presence of this, er, companion absolutely essential to the success of your vacation, I wonder, Sandilands? You refer to her as an impediment. Quite understand your position. Most chaps would be only too glad to use the opportunity of an emergency posting abroad to get off by themselves. I’ll be pleased to put it in writing . . . tiddle it up and make it look official if that would smooth a few feathers . . . ease your path. I’m sure I don’t need to remind you that female companionship – if that’s what you’re after – is available and of a superior style in France.’

Redmayne sat back, pleased with his solution. He exchanged an old soldier’s knowing smile with the handsome young man sitting opposite. He didn’t think he’d assumed too much. As well as the details he’d picked out from Sandilands’ file he had had a full report from Sir Nevil and, indeed, had even met the man in a social context on one or two occasions. You never quite knew where you were with a Scotsman but first impressions had been most favourable. Undeniably a gentleman, impeccable war record. He was, to date, unattached and that suited his department. With no wifely or domestic concerns, he had always shown himself ready to move at a second’s notice from his bachelor apartment in Chelsea without demur, travel any distance and take on any task, Nevil had assured him. But this was a state which could not, realistically, be expected to last. The Brigadier sighed. This promising chap would soon, inevitably, announce his decision to settle down in some green suburb with wife, children and labrador. Redmayne dismissed this gloomy picture. With a bit of luck he might just turn out to be that useful thing – the eternal bachelor. Still in his early thirties, fit, active and charming company. Thick head of black hair, neatly barbered. Quiet grey eyes. Pity about the face. The war wound. Still, there were those, mainly women – and Lady Redmayne one of them – who maintained that the crooked brow was most intriguing and gave a certain mystery to the otherwise clear-cut features.

Sandilands was speaking again in his low voice which still retained a slight Scottish huskiness. Another of the man’s attractions apparently. But, on this occasion, he was intrigued to hear an unaccustomed note of hesitation.

‘Quite agree, sir, and I only wish it were so easy but the scenario is quite a different one. You see, the female in question is a child. My niece. At least, my honorary niece. Little Dorcas Joliffe, the daughter of Orlando, the painter whose sister –’

‘The Wren at the Ritz! That Joliffe? Beatrice Joliffe? Done to death three months ago . . . Yes, of course I know about that disgraceful affair. Good Lord! Are you saying you’re still in contact with that rackety family? Believe me, Sandilands, you owe them no consideration. Your professional attentions ought properly to have ceased at the closing of the case. Surely Nevil . . .?’

‘Orlando is an entertaining and talented fellow and, yes, I’m proud to count him my friend. His children, who, as you know, are motherless and live like gypsies, have been taken under the wing of my sister Lydia who lives quite near to them in Surrey. The oldest girl, the impediment referred to earlier, this Dorcas, is, oh . . . fourteen? (Not sure she knows herself.) She’s become particularly attached to my sister’s family and seems to be living with them in the capacity of third daughter. Waifs and strays have always gravitated towards my sister and she’s made something of a project of young Dorcas. Clever little thing. Most unusual. It was her observation and insight that led to the uncovering of her aunt’s murderer.’

‘What extraordinary company you keep, man!’ said Redmayne. ‘And what’s all this nonsense about “waifs and strays”? Hardly a description of the Joliffe children, I’d have thought? Pots of family money in the background. Good home in leafy Surrey. Yes? Death and treachery swirling all around, as all admit, but a respectable grandmother to keep the lid on. I understand she has wisely done her best to minimize the impact of her daughter’s scandalous behaviour and sudden death. And it suits us to support her in this. Beatrice Joliffe died in the course of a robbery . . . we must all hang on to that. The old lady, at least, seems to have got the picture. Should be enough to protect those children from the public opprobrium which might otherwise have come their way.’

‘Deprivation can take many forms, sir, and these children have been rejected by their grandmother – on whom they are materially dependent – on account of their illegitimacy. Rejected with inexcusable and unnecessary cruelty, some might say. Their father, fond though I have become of him, is feckless – not uncaring but inadequate . . . say rather, perpetually distracted. When his model and current mistress, herself heavily pregnant, set fire to his caravan (and Orlando inside it at the time, under the influence of something or other) the eldest child, Dorcas, suffered burns whilst helping to rescue her father. Sister Lydia leapt in, scooped up the whole brood and took them home with her to introduce them to the civilized life.’

‘Don’t recall hearing any of this penny-dreadful, Perils-of-Pauline stuff from Nevil?’

‘No, sir. These skirmishings post-dated the premature closing of the case.’ Joe did not attempt to hide his disapproval.

Redmayne chose not to pick up the implied criticism of the military pressure which he was quite aware had been applied. ‘And the child is now loosely under the protection of your sister? A public-spirited gesture. Admirable woman! But I can’t see why her self-sacrifice should extend to and involve you, Sandilands.’

‘Oh, people do occasionally talk me into undertaking unwelcome projects,’ Joe said genially. ‘Orlando gathered his remaining four children together with his current mistress, put them aboard a train and went off to the south of France as he does every year. He carouses all summer at a sort of awful artists’ jamboree – returning in the autumn. He hobnobs with the likes of Georges Braque, Matisse, Picasso . . . Augustus John, I shouldn’t wonder . . . All egging each other on. At this time of year, my sister travels in the opposite direction, going north home to Scotland, and Dorcas, discovering this, kicked up a fuss. She thinks of herself as a Child of the South, which, indeed, she very much appears . . . girls with her dark looks are thick on the ground in Arles . . . and I was cajoled into escorting her down through France to whichever villa they’ve all descended on and there I hope she will rejoin her father.’

‘A sorry tale. I fear you allow yourself to be used too readily, Sandilands. Disappointing that you have let yourself become so embroiled in that family’s affairs. They must all, inevitably, be tainted in some minds . . .’ Redmayne swept a warning glance up to the ceiling. This was his way of referring to the shadier elements of the government departments concerned with aspects of national security who were rumoured to have offices complete with the latest in listening technology situated in remote parts of the building. ‘. . .tainted with the scurrilous behaviour and treachery of that woman,’ he finished with tight-lipped distaste.

Joe had noticed that the few people who needed to refer to Dame Beatrice did so in a hushed voice and called her ‘that woman’. The words ‘espionage’, ‘blackmail’ and ‘traitor’ were always in mind but never spoken.

‘Hum . . . Look, take the girl with you.’

This was an order not a suggestion. ‘Might work in our favour. Give an impression of a cosy family visit, policeman on holiday with his niece, relaxed, convivial. You could well learn a lot more – and faster – that way. And let’s not forget Houdart Fils! He’s, as you calculated, sixteen.’ Redmayne smiled with satisfaction. ‘Does this Joliffe child speak any French?’

Joe recalled with dismay the fast and colloquial street French Dorcas had picked up trailing about after her father in the loucher parts of the Riviera. ‘Fluently,’ he said diplomatically.

‘She does? Good. Yes, this might all work out to our advantage. Look here, don’t hesitate to telephone us if there’s anything we can supply. Full back-up guaranteed. Shan’t be at my desk myself unfortunately. Like your sensible sister, I’m going north for a week or two.’ He glanced at the dramatic Victorian paintings of stags at bay and frothing Scottish salmon streams hanging on his panelled walls and sighed with satisfaction. ‘But there’ll be someone here keeping communications open.’

‘Telephone?’ said Joe morosely. ‘Do they have the telephone down there?’

‘They certainly do. Halfway between Paris and Reims, you’d expect it. Things have changed, Sandilands, since you were dodging German shells over there eight years ago. No one like the French when it comes to reconstruction. Still, when you come to think of it – they’ve had a lot of practice, poor souls. Look at it this way – sorting out Charles-Auguste’s little problem is the teeniest bit of last-minute reconstruction. Least we can do, wouldn’t you say?’

At this point Joe, mystified and discouraged, sighed and surrendered the pass.

‘Now. To business!’ At last the file was opened and Redmayne pretended to riffle through it. He had clearly made himself familiar with the contents and barely needed to refer to it during his briefing.

‘Know anything about shell-shock? Or the condition we must now call “neurasthenia” or “war psychosis”?’

‘I’ve encountered cases, sir. I can’t say I’ve made a study of it.’

‘Well, you’re going to have to. We have, naturally. In fact I’ve managed to put together a few papers here outlining the very latest thinking on the condition. Make yourself familiar with them. It may help you in your enquiry.’

‘My enquiry? And does it have a subject, my enquiry?’

‘Of course. But not what I gather to be your usual kind of subject. No rotting corpse on offer, no member of the aristocracy done to death in mysterious circumstances. No, the reverse, in fact. You’ll be helping to solve the mystery of someone who’s decidedly (and rather inconveniently) alive.’

He produced from the file a cutting from a French newspaper. The article occupied the whole of the front page and carried a large portrait photograph. Joe took it and translated the headline. ‘Do you know this man?’ He studied the photograph for a few moments and looked up. ‘Of course I know him. Doesn’t everybody?’

‘What! Are you serious?’

‘But his face is everywhere in London at the moment. On billboards ten feet high. It’s Ronald Colman.’

Pleased to have puzzled his boss he added kindly, ‘The film actor, sir, but a Ronald Colman after a heavy night out on the tiles, you’d say. Looks rather beaten up. You haven’t seen him in Her Night Of Romance? . . . Lady Windermere’s Fan? And most recently Beau Geste? Oh, an excellent film! I do recommend it. I’m sure Lady Redmayne could tell you all about him. The gentleman is English by birth, wounded in the war and now making a name for himself on the silver screen in America.’

‘Do be serious, Commander.’

Joe smiled. ‘The resemblance is, actually, quite striking.’ He looked again at the finely drawn, handsome face with its neat moustache.

‘Interesting. Ramble on, will you. First impressions are usually worth hearing. When they’re not flippantly delivered.’

‘No, I agree, sir, this could not possibly be a screen actor. This man is unaware of or indifferent to the camera. He’s not seeing the photographer, you’d say. He’s not looking in that slightly embarrassed way we have to the side or past the lens or narcissistically into it. His expression is impossible to read. A mask. There are signs of a wound along his jaw and I’d say he was about two stones underweight.’ He began to read out snatches from the accompanying text. ‘The man of mystery was found wandering around a railway station . . . It’s thought one of a batch of late-release prisoners from a German prisoner-of-war camp for the mentally ill . . . Poor chap. That would account for his vacant expression. The man cannot speak, has lost his memory and has been passed along from one asylum to another, fetching up at Reims where he is thought to have originated. The director of the asylum . . . um . . . from a swift perusal of this report I’d say he would seem to be a splendid fellow . . . has interested himself in the stranger’s case and taken this unusual step to try to establish his identity and locate his family.’

Joe looked up more cheerfully. ‘Well, I can’t see a problem there. A man with such striking looks must have been instantly identified, wouldn’t you think?’

Redmayne sighed. ‘And there’s our problem, Sandilands. Would you believe – over a thousand families from all over France have claimed him! They’ve mobbed the asylum demanding to take him home with them. And, as you might guess, most of the claimants are female! Mothers, wives and sisters by the dozen. All desperate to get their man – or perhaps any man – back from the front after all these years. Poor devils.’

‘Easy enough to rule out most of the candidates, I’d have thought. Just a matter of process. Now I’d have –’

‘Yes, yes. Whatever you can think of, the French authorities have already done. Height five foot eleven, fair hair, blue eyes. Well, in a country of largely dark-haired, dark-eyed inhabitants, those facts ruled out ninety per cent of the bidders for a start. He didn’t feature in their Bertillon files so – no criminal record. Unless he went uncaught during his career of course. There’s always that. The French police only record the sportsmen they’ve actually apprehended and put behind bars.’

‘Fingerprints, sir? Have they explored the possibilities? I know the system hasn’t captured the French imagination – so much invested in the Bertillon recording method – but surely a comparison would be possible and most revealing? I understand their police laboratory in Lyon to be in advance of anything we can supply ourselves here in London.’

Joe heard the touch of eagerness in his own voice and sighed.

Redmayne hurried on, playing his fish with confidence. ‘Other physical details like limbs broken before the war . . . presence or absence of . . . eliminated a few more candidates and the upshot is – the authorities were left with a solid core of four claimants who will not be discouraged. They are all perfectly certain that the man belongs to them. Here’s a list.’

Joe took the sheet of paper and read out one by one the names and addresses of the claimants. ‘Number one: Madame Guy Langlois. A grocer’s wife – or widow, do you suppose? From a village near Reims. Claims to be his mother. Her son, Albert, disappeared during the first battle of the Marne.’

‘“Missing in action. Presumed to be dead,”’ supplied Redmayne. ‘But no body was ever found and no identification medallion handed in.’

‘Number two: a Mademoiselle Mireille Desforges of Reims, claiming a “certain relationship” with the mystery man from before the war, vows she can identify him to everyone’s satisfaction by particular physical characteristics not yet revealed to the public. “A certain relationship”? Rather coy phrasing from our confrères?’

‘Yes. Family newspaper. Probably means he was her what d’ye call it? . . . her pimp? And the “satisfaction” she promises would undoubtedly be her own. Chap probably made off with her money in the way of those gentlemen and the lady wants to retrieve some of it.’

‘Number three: a whole family, evidently. The Tellancourts. Small farmers from the Reims area. Brother and sister adamant that this is their older brother Thomas.’

‘Some urgency to their claim. Sad case. Lost almost everything in the war. Father and mother are still alive and equally certain of their identification. They present a strong claim. Whole village has come out in support. Papa Tellancourt is very ill and not expected to last much longer. They are vociferous in their cries for an early decision. They were actually caught in the act of smuggling the chap out of the institution,’ he smiled, ‘in their eagerness to acquire him.’