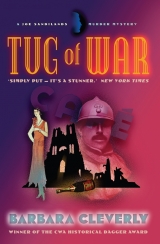

Текст книги "Tug of War"

Автор книги: Barbara Cleverly

Жанр:

Классические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

Chapter Twenty-Nine

They ordered breakfast sitting on a café terrace in the sunshine while it was still cool enough to be comfortable. Crunching his way through his first croissant from the pile of still-warm rolls served in a napkin inside a silver basket, Bonnefoye stopped chewing, wiped his mouth and spoke to Joe in a low voice.

‘I wonder if you’ve noticed . . . will be surprised to hear . . . that your niece is also taking breakfast at the Café de la Paix? And she’s not alone. She is accompanied by a gentleman. Odd choice of escort, I’d have said. They’re sitting four tables away, north-north-west.’

Joe was alarmed and puzzled. He’d slipped a note under Dorcas’s door which clearly said he’d left instructions for breakfast to be brought up to her in her room and she was to stay there until he returned. He risked a quick look over his shoulder in the direction indicated. Dorcas caught his eye and waved to him. He identified her escort at once and turned back to Bonnefoye with a relaxed smile.

‘All’s well. I know the gentleman. Nice chap. He’s staying at our hotel. He’s a mayor from a small town in the Ardennes, I think he said. Poor fellow – I’d say he’s on his last legs. He had a heart attack or something very like it just after dinner the other day. I suspect there’s not much one can do for him. Don’t worry, he’s quite safe with Dorcas. The child has had a rather sparse and unsatisfactory family for the early years of her life and it’s my theory that she goes about collecting relations. She picked up an older brother in Georges Houdart and now she’s acquiring a grandfather figure, I’d say. They were both alone in the hotel – much better to have someone congenial to chat to over the café au lait in the sunshine. All the same, I don’t think we’ll ask them to join us.’

‘A mayor? What did you say his name was?’ said Bonnefoye.

‘I didn’t. But he’s called Didier Marmont and he’s an old soldier.’

The telephone call came, as promised, exactly an hour later and Joe was able to infer from Bonnefoye’s responses that there had been results and the results were confirming their suspicions. After effusive thanks, Bonnefoye put down the receiver.

‘There we have it!’ he exclaimed. ‘A large amount of money was withdrawn from the account of Clovis Houdart in late August 1914. It was in the form of a cheque made out to one Dominique de Villancourt. Now we can’t get at his banking details but what’s the betting that this same sum of money made its way through agents and lawyers carrying the signature of de Villancourt and ended up paying for the purchase of a flat overlooking the Bois de Boulogne – it’s about the right price for such a property in 1914. The legal papers which, er -’ Bonnefoye flashed a disarming smile – ‘you may possibly not be aware that I had seen . . .’

‘Mademoiselle Desforges, at least, would appear to be the epitome of honesty and forthrightness,’ said Joe. ‘She told me you had them.’

‘Indeed. These papers, as she avowed, bear his signature and this I have been able to authenticate. The same signature also appears on the subsequent transfer of the deeds to the grateful lady. A good friend! A man happy to lend his name to a bosom pal anxious to hide his amatory activities from family and acquaintances – activities carried on within a few miles of the home he was determined to protect? Time to say hello to your elephant?’

‘I’m afraid so,’ said Joe. ‘Our Thibaud was a busy boy. Leading a life of danger on the battlefield and off it . . . But I’m thinking, Bonnefoye, that from what I’ve perceived of the French way of going on over the years – and I know you’ll shoot me down if I’m wrong – keeping a mistress, in whatever state of luxury, is not held to be a cardinal sin or even anything out of the ordinary Not a reason for all these expensive manoeuvrings, surely? And he had, from the start of the affair, told Mireille that he was a married man.’

Bonnefoye nodded his agreement and waited to hear more.

‘So why the rather desperate attempts at concealment? I think we’re looking at this from the wrong perspective. I don’t think Clovis was hiding his wife from his mistress. I think it was the other way around. Don’t you think that perhaps Clovis was all too aware of the strength of his wife’s emotional surges – her unpredictability? And was at pains to shield his lover from her,’ he added thoughtfully. ‘Having seen the lady at close quarters, I must say, I’d rather face a charge of Uhlans than an Aline Houdart who’d just discovered that her husband was madly in love with another woman, intending to leave her for a nobody – a little seamstress from Reims. Or even worse – intending to send her back to her parents in Paris and retain his son and his life at Septfontaines. I’m just surprised that he managed to get away with his throat uncut. On that occasion.’

‘But you tell me that Aline was herself conducting an affair . . .’

‘The fact that she was betraying him would not weigh heavily with Aline. Charles-Auguste said it – “What Aline believes to be the truth becomes the truth.” He thinks his cousin may be a little . . . there may be a slight cerebral . . . not sure what the correct medical term would be . . .’ Joe finished delicately.

‘Crazy?’ said Bonnefoye. ‘I had wondered! And if you were married to her wouldn’t you want a Mireille in your life? I’ve got to know Mademoiselle Desforges slightly in the course of this case and I have to say, Sandilands, that were she not so earthy, so worldly, so full of life and mischief we’d have to say she was an angel.’

He sighed a very Gallic sigh.

‘But she’s about to be a disappointed angel, I’m afraid,’ said Joe. ‘Clovis and Dominique are one and the same and there’s no separating them. I suppose we could take a leaf out of King Solomon’s book in the matter of assigning possession but I’ve always thought that a very chancy procedure. In law the man must be returned to his rightful home and the bosom of his family. You’re going to have to make the decision, Bonnefoye. Sign the forms. Yours is the finger on the pen.’

‘Correction,’ said Bonnefoye. ‘We’ll have to make the decision. I’m not bearing the weight of this alone. We will summon the good doctor to a conference and he as the medical authority in the case, you representing Interpol and I as the case officer, will come to a unanimous decision. This afternoon. This has gone on for quite long enough. We’ll do this at the hospital. Can you attend, let’s say after lunch at two o’clock?’

‘I’ll do that,’ Joe nodded. ‘So – we have an identity. The unknown soldier is unknown no longer. I wonder if the general public will remain enthralled by the story?’

‘Perhaps – if we were to tell them the whole tale. But I shall give out a severely edited version. I don’t know about you, Sandilands, but I got quite fond of the old bugger – Clovis, I suppose we should get used to saying. I’d like the rest of his semi-life to be as uncomplicated as possible. And I’ll deliver a strongly worded warning about patient-care to la Houdart before she takes delivery, don’t worry!’

‘Poor old Thibaud,’ said Joe sadly. ‘I shall always think of him as Thibaud, I’m afraid.’

Chapter Thirty

‘I have the strongest misgivings about this. You may only come if you swear to stay in the background and not protest about the decisions taken. You know what you’re like. This is official business. A man’s life and future are at stake, to say nothing of three men’s reputations – I won’t have you sticking your oar in.’ He flicked open his napkin in a decisive manner.

‘Very well, Joe. Of course, Joe. If you’re going to be such a fusspot, I’d really rather not go at all. I’ll stay behind and do a little souvenir shopping. And your appointment’s for two o’clock?’ Dorcas looked at her watch and frowned. ‘If we have a quick lunch we’ll have time to pack up the car and get straight off afterwards and then we could be in Lyon by this evening.’

He was pleased to be distracted by a practical arrangement.

‘Never sure you’re to be trusted. Going off on your own like that this morning! Marcus warned me to treat you like Carver Doone . . .’

‘Who?’

‘His pet ferret. Rabbiter. Half trained he was. Never lived to be fully trained. Nine times out of ten he’d do what was expected of him but on the tenth, he’d run away and go wherever the fancy took him. Gone for hours. One day, poor old Marcus was discovered shouting vainly down various rabbit holes one after another, ordering the villain to come out at once or else. Suddenly, there was the most awful scream and Marcus raised his head from the hole with Carver Doone attached by his fearsome little teeth to his nose. It led to a painful separation. Now, something light, I think you suggested . . . And while we’re choosing, why don’t you tell me what you were talking about so earnestly with old Didier?’

‘He’s a wonderful man. A soldier. Something of a Bolshevik, I’d have guessed. He was telling me about his daughter Paulette and her American husband. He’s devoted to his family. He’s got a baby grandson called John. Only six months old. He knows he’s dying, Joe, and can talk about it as though he’s just going on holiday. So matter of fact. I expect it was the truly awful time he had fighting on the Chemin des Dames that ruined his health.’ She thought for a moment and then went on: ‘Have you noticed, Joe, that throughout this case that name has kept coming up like a chorus in a song? Everywhere we turn it seems someone’s whispering about . . . what would you say in English? The Road? Path? Of the Ladies? Which ladies? And which road?’

‘The Ladies’ Way, ’ said Joe. ‘A pretty name for a blood-soaked piece of country. North-west of Reims. The ladies were the two aunts of Louis XVI – the one who was guillotined after the Revolution – and the way was their favourite coach-ride along a high bluff overlooking low-lying plains to north and south. A fearsome strategical position since the Stone Age. Any army wanting to defend Paris has to hold that height.

‘And – chorus, you say!’ Joe shivered. ‘Have you ever heard it, Dorcas, the song that came out of that battle? The song of Craonne? The song of the mutineers? It has the most haunting of choruses.’

‘I don’t know it.’ She looked around her. ‘We’re out of earshot and we’re English eccentrics anyway – why don’t you sing it? You can always stop if the waiter comes.’

‘I warn you – I rarely manage to get to the end of it, it’s so sad,’ he said and, self-consciously, but confident of his baritone voice, Joe leaned over the table and began to sing.

Adieu la vie, adieu l'amour,

Adieu toutes les femmes,

C’est Men fini, c’est pour toujours,

De cette guerre infâme.

C’est à Craonne, sur le plateau,

Qu’on doit laisser sa peau.

Car nous sommes tous condamnés,

Nous sommes les sacrifiés.

Unusually, Joe managed to get through the lilting song dry-eyed but hurriedly passed his handkerchief to Dorcas.

‘Sing it again slowly and I’ll translate as you go, if I can keep up.

‘“Goodbye to life, goodbye to love and goodbye to all women . . . It’s all over – for ever, this terrible war . . . It’s up there in Craonne, on the plateau, where we must all leave our skins? . . . Die, does it mean? . . . For we are all condemned. We’re all to be sacrificed.” They don’t sound like – what did you say? – mutineers, Joe. They’re saying goodbye, they know they’re going to lose their lives. It’s far too sad, too hopeless to be a song of revolt.’

‘It was a very strange revolt. And yet the army authorities were so afraid of the power of the song to move a whole army, a whole people perhaps, that they banned it and offered a huge reward to whichever soldier would turn in the man responsible for writing it. And, do you know, Dorcas, the money went unclaimed. No one betrayed the song-writer. And they all went on singing it.’

‘I’ve never heard of this. But then I don’t know much about the war.’

‘No one knows very much about this part of it. Even the English army fighting on the flank were not aware that the French had downed tools and declared they’d soldier no more. And yet that’s not exactly right – they never surrendered. They were not traitors. They held the line but declared that they would not advance another inch until peace had been declared. They were holding out for a settlement.’

‘You say the English didn’t know about it? Did the Germans find out?’

‘Those of us in British Intelligence who knew conspired with the French to keep the lid firmly on. And – goodness knows how – it worked. The German trenches were only a few yards away from the French front line in places and no rumour reached them.’ He shuddered. ‘One man caught in no man’s land and made to talk, one man deciding to go over to the enemy, and it would have all been over for us. They would have called up forces from the east and poured everything they had on to the weakened French lines and broken through.’

‘Poor Didier. And poor Clovis. He was up there too, wasn’t he?’

‘I believe he was. He killed Edward and then rode off into the night and back into battle as far as we know, expecting to leave his hide up there on the plateau with all the other sacrificial victims.’

‘I wonder what happened to the rebels? Do you know, Joe?’

‘I know. It’s very unpleasant and I’d really rather not talk about it, Dorcas. Not for your sake – for mine. Now – omelette do you? Or would you prefer steak-frites?’

Varimont, Bonnefoye and Sandilands sat down together around the table in the doctor’s office as the hospital bell sounded two o’clock. Bonnefoye produced the papers to be signed and succinctly set out the case for assigning custody of Thibaud to Aline Houdart.

Joe intervened at this point to voice his concerns about the welfare of the patient if such action were followed, and this was seriously considered by Varimont who questioned and evaluated his information. ‘This is indeed a cause for concern as Sandilands says, Bonnefoye,’ said the doctor. ‘Look here – there is a third way of doing this which perhaps in the light of Sandilands’ insights we ought to consider. Don’t assign him to anyone. I’m perfectly willing to hang on to him here if, truly, no better situation is available to him but – well, you’ve seen it. It’s not ideal. I am however very interested in Thibaud and his condition – and neurasthenia of war as it affects other unfortunates – and I’m making something of a study of these cases. It would be interesting to see how he reacts if transplanted into neutral surroundings.

‘Look – I would be quite prepared to tell the press and anyone else who’s interested that his identity remains unproven and he is being lodged with a third party, nominally under the control of the hospital, so that our experiments may continue and observations be made. Should this type of care prove successful the government will be only too pleased. Too many such cases clogging up the public health system.’

‘It’s a thought,’ said Joe. ‘Find and register a caring townsperson willing to liaise with the hospital.’

‘He’s Aline’s husband,’ objected Bonnefoye. ‘He’s Clovis Houdart. We can’t get around that. We have the widow’s identification, which I would now declare to be incontrovertible.’

‘But an identification which is stoutly questioned, let’s not forget, by his son and his cousin,’ the doctor objected. Then, startled, he looked at his watch and exclaimed: ‘Oh, great heavens! I have to tell you – I have a further appointment this afternoon. No, don’t be concerned – we won’t be interrupted. I’m intending to run it alongside this one. I had a most insistent call from a witness the other day. A man who claims to know Thibaud. An old army colleague. He’s only just recently come across the photograph apparently but is one hundred per cent certain – aren’t they all? – that he knows our man. As he was able to give me a name and rank – Clovis Houdart, Lieutenant Colonel – I thought it might be worth giving him a crack at it, bit of extra weight in the scales, one way or another. I wouldn’t see him right away – Thibaud has been disturbed by all the comings and goings and I thought I’d give him a weekend off. But now – he’s due in ten minutes’ time – we could all go with him to Thibaud’s room and chalk up one more positive identification. Or not. You never know!’

Joe could not be certain that Didier Marmont was pleased to see him. The one short flash of uncertainty was so soon followed by a warm and gracious recognition that he thought he might be wrong. He had clearly not been expecting a reception by two policemen as well as the doctor but took the introductions in his stride.

Approaching Thibaud’s cell he showed signs of nervousness but made a joke and entered following Varimont.

Eyes turned immediately on Thibaud. He was sitting, exactly as before, forlorn, on the edge of his bed, staring into the wall. His hair had been freshly washed and trimmed and he was looking smart, slender and almost waif-like in white pullover and black cord trousers. Joe’s eyes however were fixed on Didier. He wanted to catch his first reaction. What was he hoping for at this late stage? A derisory ‘What’s this? No – that’s never Clovis Houdart!’ Yes, he could not deny that was his hope.

But Didier knew the man at once. His eyes widened, he caught his breath. He strolled over to Thibaud and looked carefully into his face. Putting out a finger, he gently traced the line of Thibaud’s broken jaw and nodded.

He turned to the assembled company. ‘This is Clovis Houdart. Lieutenant Colonel Houdart of the Fifth Army, last encountered serving under General Pétain. Summer of 1917. Soissons-Auberive sector.’

‘You served in the same company?’ Joe asked.

‘I was just a corporal, called up as a reservist. My age, you know. By that stage they were using even old wrecks like me. There were three generations shoulder to shoulder in the trenches.’

‘But it wasn’t the first time you’d soldiered?’

‘No, I fought at Sedan. Experience was a help, in fact. I tried my best to calm the troops. Father-figure, you know. “Think this is bad, lads? You should have seen . . .” You know the sort of thing.’

‘Soissons, you say?’ Joe asked quietly. ‘You were caught up in the Mutiny?’

Bonnefoye and Varimont exchanged looks.

‘I know – I’m not supposed to know anything about that,’ said Joe. ‘But I do. I was in Military Intelligence.’

‘Then you’ll know how low morale had sunk by April of ’17?’ Marmont was pleased not to be called on for an explanation. ‘I was given a squad of boys, fresh meat, straight off the farm. One day in the front line was enough to send them mad. They couldn’t understand why we’d suffered such an assault, accepted such a stalemate for three years. They were fighting from the trenches their dead predecessors had dug and occupied three years before. Not an inch had been gained and the trench walls were revetted with the bones of French and German alike. General Nivelle had built up our hopes. One last push, he’d said. One more concentrated attack and we’ll carry the day. We went into it with spirit but months on we were bogged down, thousands dying every day. Food disgusting when we had any. No leave. Weeks sometimes in the front line with no reprieve. My lads were given suicidal orders to go over the top. Few ever came back.

‘But one lad kept coming back. Grégoire, his name was. Seemed to bear a charmed life. You see that every so often. Must have come in for all the luck allocated to his family – his brothers had all copped it. His parents were dead. No family left. I took him under my wing. Tried to advise him when he went over to the rebels. He lived long enough to get a short leave in Paris. The men were bombarded at the stations by pacifists. Bolsheviks? Patriots? I still don’t know. But Grégoire and others like him returned and spread the word. Rebellion was raging through the troops. Unpopular officers were stoned . . . disappeared quietly in the night . . . Trains were commandeered and driven to Paris . . . Desertions increased . . . Forty thousand men grounded their muskets. The lads said they’d man the trenches, hold the line, but they wouldn’t attempt to go forward another inch until they got what they wanted: peace. Someone was going to have to sign a treaty. I’ll never know why we weren’t instantly overrun by the Germans. But they never seemed to catch on to what was happening in front of their noses.’

Joe’s voice broke into his monologue, an interested fellow soldier going over a battle plan. ‘Might have something to do with the discreet though disastrous attempt by the British top brass to distract them from the French lines. They knew the dangers of the Soissons-Craonne sector. We made a feint – a push to draw the German forces away from the French and on to ourselves. And our effort to help out resulted in the appalling losses of the third battle of Ypres. You may know it as Passchendaele. We were suffering alongside you, Didier.’

Had he heard? The content of Joe’s short speech would normally have been provocative enough to stoke a whole evening’s conversation and argument. But Joe’s tone seemed to calm him. Marmont turned, his attention caught, and spoke directly to him, needing to explain himself, a link established with this friendly stranger who seemed to understand him. An elderly doctor and a young policeman were a less acceptable audience, it seemed, than a man who had survived Ypres. ‘Don’t blame them. They weren’t traitors! Poor buggers just wanted the noise to stop, to be able to go home. They wanted the war over by the fastest means. They had honour. They loved their country. They still had within them an unquenched spark of independence and the spark flared into something uncontrollable up on that ridge near Craonne.

‘And this is where our hero comes into the story.’ He indicated Thibaud who had heard not a word. ‘I expect you wonder why on earth I’m rambling on, wearying you with my memories. Where I’m going with this.’

‘Nowhere good,’ thought Joe, but he assumed an attitude of entranced listener. Not difficult as he was fascinated to hear more of Clovis from someone who had known him on the battlefield. Instinctively, he moved forward a few paces, steady and unthreatening, positioning himself in front of Varimont and Bonnefoye, focusing all Marmont’s attention on himself.

‘Top brass kept the lid on but it couldn’t last. Nivelle was sacked and Pétain was brought in to clear up the mess. Better food, more leave and promises got the men back at it again. But there was a stick as well as a carrot in this equation. We were going to be made to pay . . .’

Joe felt an icy trickle of foreboding along his spine.

‘An example had to be made. Thousands of mutineers were arrested and court-martialled. Over twenty thousand were found guilty. Whole companies, every man jack of ’em. Four hundred were condemned to death. Fifty were actually executed. They say fifty . . . ‘He shrugged his shoulders. ‘And the rest! Nobody ever declared the retributions carried out in fields and ditches. And the red-tabs who organized all this – not worth our spit! Becs de puces! Peaux de fesses!’ The poilu’s crude curses burst from him. ‘They made us kill our own men using firing squads made up of their fellows. “Pour encourager les autres!” they said. “Pour l'exemple!”

‘They drew lots to decide who would be punished! Can you imagine that? Can you? Lining up and shuffling forward to take your life or your death from a tin cup! Funny though – I don’t know if many noticed, but the lads who were picked out for execution had something in common. They didn’t count for much with anybody. Lads with no family to make a fuss about their execution afterwards. Lads like my Grégoire.’

Joe didn’t want to hear any more but they all listened on in awful fascination.

‘I was put in charge of the squad detailed to execute him. He took it bravely . . . wouldn’t have expected anything else. I sat with him all night holding his hand and praying before that dawn. I’d done everything. Pleaded with the commanding officer. Offered a substitute . . . Deaf ears. “Orders . . . orders . . . nothing we can do . . .” You’ve heard it.

‘We fired. Of course, we all shot wide. I damn nearly swung round and put my bullet through the commanding officer who was officiating. Wish I had. Grégoire didn’t drop. He was wounded in the shoulder but not dead. And then the CO stepped forward, cursing us, and drew his pistol. It was routine. It was expected. But it still churns my guts. The swine put it to Grégoire’s head and shot him.

‘It was a pistol just like this.’

Marmont pulled a Lebel service revolver from his pocket, took a step towards Thibaud and held the gun to his temple.

‘And this was the officer.’

They waited, helplessly, for the shot, the coup de grâce so long anticipated.

Joe didn’t think Marmont was savouring the moment – there was no triumph or gleam of vengeance in the man’s face, nothing but disgust, loathing and pain. ‘I lost my rag. I rushed him and clobbered him with my rifle butt. Glad to see he bears the scars. Hope it hurt like hell. I spent the rest of the war in a punishment squad. Shouldn’t have survived. And I thought this bugger must be dead. Lieutenant Colonel Houdart. And then I saw his photograph in a newspaper a week ago.

‘There are two bullets in here. The first’s for him and the second’s for me. Gentlemen that you are, I count on you to do the decent thing and just give me time to turn the gun on myself, will you?’

They stared, unbelieving, at Clovis Houdart’s expressionless face, chlorine pale, a fragile thing against the black gun barrel. A vein throbbed in the temple and Joe wondered for how many more beats it would pulse with life. Each man knew that there was a soldier’s steady hand on the pistol, a determined finger on the trigger. The skull would shatter before a move could be made towards him.

Into the silence Joe’s voice spoke, light and conversational. ‘If that’s really what you want, then I’m sure we can do as you wish. And you will go, knowing you have our sympathy and our understanding because, Didier, we’ve heard your story. And these tears running embarrassingly down my face in an unmanly way are for Grégoire and all the other poor sods who suffered.’

For a second Marmont’s eyes flicked sideways to Joe. Joe pressed on: ‘But isn’t there another name we should be hearing? John – your grandson, John! How old is he? Six months? John.’ He repeated the name with deliberation. ‘He too plays a part in all this.’

Marmont directed another look at him in dawning surprise. ‘Grégoire,’ Joe said again respectfully, acknowledging with a nod of the head the presence of the dead soldier in the room as an honoured guest, ‘Grégoire is remembered. He stands with us. For as long as you are with us to tell us his story. But Grégoire is the past. And John is the future. John will never hear your words of suffering – of explanation. What will he grow up knowing of his grandfather? That he was a brave soldier who gave his all for his native land, who survived against overwhelming odds to hold him in his arms and tell him stories, or – that he is a man never spoken of in the family? A man surrounded by silence and mystery until one day someone tells him his grandfather murdered a defenceless lunatic and then turned the gun on himself. Will he understand, do you think?

‘Look at your target. Take a good look at him. There’s nothing there, Didier. You might just as well fire your bullet into that pillow. Don’t sacrifice your honour, your years of suffering, your grandson’s memory of you, for this empty shell. Give me the gun. And that’s an order, mate! And, Didier, let’s make it the last order you ever take from an officer. From an officer who’s listened, understood and suffered alongside.’

Marmont made no move to lower the gun but his eyes were looking from Clovis to Joe and back again.

The first sign of indecision.

Encouraged, Joe spoke again, taking his time. ‘Look – in the circumstances, I’m supposing you haven’t made any plans for the rest of the day? Well, I have but I’ve decided to put off my departure today to take you out to dinner. My niece, on whom you seem to have made quite an impression, would insist. This calls for a bottle of the best. Not champagne perhaps but a Château Latour. And here’s a joke – we’ll put it on the expense account of the British War Office! Mean buggers! I’ll tell them it was drunk to celebrate two lives saved. Yes, a Latour. I’m sure they’ll have something good to eat with it?’

Confidently, almost casually, Joe started to cross the room.

He reeled back as the gun crashed out once and then again, deafening in that small space. Bonnefoye threw himself to the ground, drawing his pistol as he dropped. Varimont cursed loudly. Joe, shocked, found himself unable to move forward. He began to cough and sneeze and then burst into nervous laughter as he flapped at the snowstorm of feathers descending on all their heads.

The old man stayed for a moment, frozen, staring at the unseeing Thibaud. The officer’s face was only inches from the blackened pillow which had taken the blast but he registered no emotion. Marmont shook his head and looked at his gun, uncomprehending. But Joe understood. Understood that the gap between the height of emotion to which the old soldier had hauled himself and the depths of bathos to which he knew he must plunge could only be bridged by an explosive reaction. The two bullets were always going to tear their lethal way down the barrel and Joe thanked God that Didier had, in the end, had the strength to divert them by a few inches.

He handed his smoking revolver to Joe and slumped in exhaustion as the doctor hurried forward, clucking with concern and reaching for his pulse.

‘We must try not to bore her with too many old soldiers’ stories, then,’ Didier grated out at last, and added, with a wheezing grimace, ‘as we enjoy our . . . ah . . . what would you say to civet de lièvre à la bordelaise? Or they had a bisque de palombes aux marrons on the menu for today, I noticed.’ He shook for a moment with silent laughter. ‘Can’t say I studied today’s menu at length. Wasn’t expecting to eat again.’