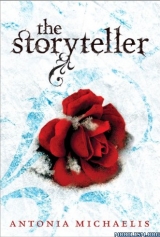

Текст книги "The Storyteller"

Автор книги: Antonia Michaelis

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

“Anna has to go now,” Abel said. “She’s got her own home and a lot to do there.” He didn’t touch Anna. He didn’t push her out of the room. He just looked at her. She held up her hands, helplessly, and walked toward the apartment door. Abel didn’t take his eyes off her as she put on her jacket and shoes. “Your bicycle is outside,” he said. “I rode it here.”

“My … bicycle? It was … locked?”

“With a combination lock,” Abel said, “the kind that anybody can open. I guess you’ve got the money to buy a better lock when you find the time.”

She made one last try. “Abel, I just brought Micha home! You asked me to do that.”

“I asked you for nothing,” he said in a hard voice. She had been wrong. He could be scary without the black hat. “It was your idea. And, now, leave us alone. Thank you for bringing her the key.”

Never had the words Thank you stung like that, like a blow. She ran down the stairs without stopping. On the ground floor Mrs. Ketow had opened her door just a little, to listen. Anna slammed the outer door shut behind her. She was crying. Shit, she was really crying. Searching for a tissue, she found the blister pack with the white pills in her pocket. Maybe, she thought, she should take one, just so … She pressed one of the pills out of the foil and put it in her mouth. It tasted bitter. She spit it out, a white pill in white snow—like white paper waiting for letters, for words, for the next part of a fairy tale. He had locked her bicycle with the useless combination lock. She unlocked it and rode home, her head empty … white paper, white snow, white ice on a white street, white sails, white noise.

When she closed her eyes, she saw a diamond embroidered in white, embroidered onto the sleeve of a blood-red coat. Or was it tattooed onto Rainer Lierski’s bicep?

THAT NIGHT, ANNA COULDN’T SLEEP. SHE PUT HER clothes back on and went downstairs to the living room, where Magnus was still sitting in his old armchair reading the newspaper, another sleepless person, but one of the steadier sort. She looked at his big, broad figure in the big, broad armchair; they were at one, he and his chair, a rock, unshiftable, unyielding, strong. When she’d been small, she had thought her father could protect her from everything. Everything in the whole world. Children are stupid.

Next to Magnus, on the small parquet table, a relic of some trip to the Middle East, there was a bottle of red wine and a glass. Anna took another glass from the cupboard and poured herself some wine. Then she sat down on the second armchair. For a while they drank and shared the silence, Magnus focused on his newspaper and Anna on her thoughts. Finally, he folded the paper.

“What’s on your mind?” he asked.

“Nothing,” she replied. He looked at her. She shrugged her narrow shoulders. She was so much narrower than him, a slender branch in the wind. “The world,” she said.

“Yes. That’s what you look like. As if you have the world on your mind.”

“Why are people so different? Why are some happy and others unhappy? Why do some people have money and others … I know,” she sighed, “this sounds childish.”

“You could study the answers,” Magnus said, wineglass in hand. “Philosophy. Or, no … economics.”

“I need a sick note,” Anna said. “For my music class today. Two to four o’clock … about.”

Magnus raised an eyebrow. He didn’t say anything.

“When I was your age,” he started, “I also …” Then he stopped.

“Thank you,” Anna said, getting up. “And, Magnus.” She was already standing in the door.

“Yes?”

“The wine’s turned.”

The next day the white snow turned into brown mud. Anna asked Bertil if he had time to study math with her that afternoon. Gitta had a study date with Hennes.

“Unfortunately not just Hennes,” she complained, “but some other people too … rats …”

Abel came to school late and slept through geography class—they didn’t have literature that day. During break, Anna sat in the student lounge by herself. Through the window, she saw Abel talking to Knaake outside, but she couldn’t make out what they were saying. All day she’d felt like she was swimming … her feet weren’t touching the ground and her head wasn’t in whatever she was doing. Somewhere on the steps of the old concrete tower block, she had lost her grip on reality, as if a veil of tears was streaming over everything she saw. Knaake took off his round glasses and scratched his head with them. A single snowflake fell onto his nearly gray beard. And suddenly, Anna sat up.

The lighthouse keeper. The lighthouse keeper looked exactly like Knaake. The glasses, the dark blue woolen sweater, the beard—everything was right. Abel had written the literature teacher into his fairy tale. He’d come aboard to help the little queen. Knaake had promised to look for a job for Abel. Knaake was one of the good guys. She nearly smiled—but only a little. The world of fairy tales was easy: good and bad, cold and warm, summer and winter, black ship and white sails.

At lunchtime, she left Gitta and wandered alone to the bakery, the one farther away from school. When she got there, she wondered why she had come. The gleeful signs for colorfully wrapped treats with Ikea-like names made her nauseous. She wasn’t even hungry. Next to the bakery, there was a kebab stand with several tall white plastic tables in front, empty despite the lunch hour. Anna felt drawn to its loneliness, compelled by the kebab seller shivering in his thin jacket. She bought a cup of lukewarm coffee from him and stood at one of the tables to drink it. His coffee was even worse than the coffee from the machine in the student lounge. She started sketching patterns into a coffee stain left on the table.

“Anna,” somebody said. “Anna, I’m sorry.”

She started and knocked over her cup, and when she looked up, she felt coffee trickling down her sleeve. It was Abel. “Ex-excuse me?” she said.

He took a paper napkin from a plastic holder and handed it to her. “I’m sorry I made you leave,” he continued. “I didn’t know that Rainer … Micha told me. You didn’t want to leave her alone. I … I didn’t want … see, it’s not anyone’s business how we live and … I’m sorry, really.”

She had never heard him search for words before. She smiled and fell back into reality with a bang, the veil of tears ripped; her sleeve felt very wet indeed.

“It’s okay,” she said. “You’re right. It’s not my business how you live. But, for the record, my room isn’t half as tidy.”

“Did Micha take you on a tour of the ‘villa’?”

She shook her head. “Don’t worry, I didn’t see the decaying dead bodies under the bed.”

His face broke into a grin. “What about the suitcase full of stolen money or the smuggled uranium in the closet?”

“No,” she said. “Though I did wonder what the gold ingots and the machine gun were doing in the drawer with the forks and knives.” It felt good to talk nonsense. It felt good to laugh about meaningless things with Abel, like uranium in the closet.

“About the story … I’m sorry about that,” she said quickly. “We shouldn’t have read it by ourselves.”

“No, you shouldn’t have,” Abel said, but he was smiling. “Rainer …,” he went on, and stopped smiling. “Micha’s father. He … he was gone for a while … out of town … at least I haven’t seen him for a long time. And now … you met him. You understand why I don’t want him to turn up, don’t you?”

“I think so.”

“Think a little more and then take the square of the result and you’ll have the truth. He’s known around here … in the cheap bars … Michelle was a departure for him. Usually his girlfriends are more like fifteen, sixteen. If they are even that old.”

“Micha is six. That’s something different.”

“Exactly.” He picked the used napkin up off the table and scrunched it up in his fist.

“Do you really think he would … That’s a horrible accusation. If there was proof he did something like that, he would go to prison …”

Abel looked up from the napkin. His eyes glowed with a blue fire. “If there was proof,” he repeated, “he would go to prison. People are talking. I know some things. I know very well. When I …” He stopped. “Would you take the chance?”

Anna shook her head. “But there are agencies that could help, judges, court orders … custody rights … if he isn’t allowed to see her, he isn’t allowed to see her, and that’s that … there are institutions set up to protect children!”

“Anna,” he said in a very quiet voice. “You didn’t understand a thing I said.”

“No?”

“I’m not eighteen. I don’t have custody rights. If Michelle really doesn’t come back, Micha is his. Like a piece of … flotsam. Like a stray dog. Like …”

“Like a lost diamond,” Anna said.

“And that’s why it is important that you keep your mouth shut,” Abel whispered. “Do you get that? We’re living with our mother in that apartment, everything’s fine, we don’t have any problems. Do you get that? Do you get that?” He grabbed her wrist, sounding as desperate as a helpless child. And somewhere in Anna, there was, for an instant, the sense that this was what he had once been, living in the same small apartment with Rainer, and she pushed the thought far, far away—to the dark side of the moon.

“I get it,” she whispered. “I’ve never been in the apartment. And if I was … then I had a really nice talk with your mother. She and my mother listen to the same music, so that was what we talked about …”

He let go of her wrist. Suddenly he seemed embarrassed about having touched her. He looked around, but there was no one who had seen. The lonely, cold kebab seller was leaning against his stand, playing with his cell phone, lost in a world of SMS emoticons.

“I’m going to walk her home from school now,” Abel said.

“You’re not going to math class?”

“I’m going to pick up Micha,” he repeated. “This afternoon … around five … we’ll be in Wieck. Sometimes we sit in that café, out by the water, and have hot chocolate. When we have extra cash. We’ve got to do something with that stuff, don’t we?” The grin returned to his face. “And there is a green ship there that has to sail on … another island has appeared on the horizon …”

“Around five,” Anna said.

She didn’t remember Bertil’s existence till after math.

“Anna,” he said with a smile in his too-narrow, earnest face. “You’re not looking as if you understood much.”

“I did,” Anna murmured. “A few things … what?”

“We could go over the rest at my place,” Bertil said. “I’ll try to explain a few more things to you, if you can explain that last formula … you’re looking at me like I’m a ghost.”

“Yes,” Anna said. “Oh no. Shit. Bertil, I can’t come over today.”

He hunched his shoulders, which were as narrow as hers. He was too tall for those shoulders. Anna liked Bertil with his dark, unruly hair and thoughtful expressions, but today she had no time for him. Or math formulas.

“This was your idea,” he said. “You wanted to go over the formulas, not me.”

“I know, and I still do.” Math was one of the things she really didn’t understand, and she was too Anna Leemann to accept getting a bad grade on a big test without putting up a fight. “But, Bertil, not today. It’s just not going to work today. Something’s come up.”

Bertil pushed his glasses back up his nose. “Something or someone, Anna?” He looked so dead serious. As if he could read every single thought in her head, every sorrow.

“Somebody,” she said. Nonsense. He didn’t know her thoughts. She smiled at him. “My flute teacher. She called me during lunch to tell me that we have to move this week’s lesson to today. I forgot all about it till now.”

Bertil nodded. “Don’t forget to lower the saddle of your flute teacher’s bike,” he murmured. “It’s a quick release. Looked dangerous last time.”

Anna shook her head. “Bertil Hagemann,” she said. “Take a break from studying. You’re mixed up.” She knew she’d turned red. Red like a child caught doing something she shouldn’t. Of course, she knew whose bike Bertil was talking about.

Anna rode home first. She had the vague feeling that Bertil was somewhere nearby, watching her, even though she didn’t see him. She looked back a few times and told herself that she was getting paranoid. Why would Bertil follow her? Still, she’d put her backpack down in the hall at home and gone upstairs to get her flute and her notes. Paranoid. Absolutely. She rode in the direction of her flute teacher’s house for about two streets, though she wasn’t sure that Bertil even knew where her teacher lived. Paranoid. Stop it, will you! It was five minutes past five. She turned her bike onto Wolgaster Street and headed toward the water.

When she reached the turn to Wieck, it began to snow again. The café lay on the other side of the drawbridge, where the breakwater led out to sea. It was just at the end of the … no, not the cliff but the harbor arm, she thought. It looked a bit like a ship made of glass, that café, a ship full of chairs and tables and little lights on curious, bendable long necks. Anna hadn’t known it was even open in February, but the café was like a living being; it seemed to change its habits at any given time and without any reason. By the time Anna shook the snow from her hat, the big clock on the wall read five thirty. She had the sense that she was too late for the most important date of her life.

The fairy tale had started without her; the little queen had sailed on, aboard her green ship, without waiting for Anna. Maybe she had sailed away for good … There they were, sitting at the back of the café, or at the front, depending on your perspective; they sat at the stern of the glass ship, where only a glass wall and a little terrace outside separated the tables from the water. Micha’s pink jacket hung over her chair in an untidy heap, and she had put her hands around her cup as if to warm them. Abel and she were sitting opposite each other, leaning forward like conspirators, whispering. There were a lot of small tables with two chairs, but they had chosen one with a third chair, and the chair was empty. When Anna saw that, something began to sing inside her, and she forgot her worries and her guilty conscience over Bertil and math—she walked over to the empty chair, walked through the crowd of winter tourists, her feet barely touching the floor.

Abel and Micha looked up.

“See,” Micha said. “I told you she’d come.”

Abel nodded. “Anna,” he said, as if to make sure it was her and not somebody else.

“I … I hurried,” she said, “but I couldn’t get here earlier. Hi, Micha. Good afternoon, Mrs. Margaret.”

Mrs. Margaret was leaning against the sugar bowl, and Micha made her nod graciously.

“Mrs. Margaret has been very impatient,” Micha explained. “Can we start now?”

Anna sat down. They had been waiting for her. They had really been waiting for her.

“Abel said, if you’re not here by six, we start without you,” Micha said. “And he said that you weren’t coming anyway and that …”

“Micha,” Abel interrupted her, “do you want me to begin or not?”

And then Micha said, “begin,” and Anna said, “yes,” and somehow she managed to order a cup of tea by signaling the waitress—and Abel, the fairy-tale teller, opened the door to a wide blue sea and a green ship whose name was as yet unknown.

“The black ship with its black sails darkened the sky behind them. More and more, its darkness seemed to leak out into the blue.

“‘One day, the sun will disappear,’ the little queen said, and at that moment the lighthouse keeper called out from the crow’s nest high up on the mast, ‘I can see an island! Can’t properly see it, mind you—my glasses are fogged up …’

“Shortly after that, the little queen and Mrs. Margaret saw the island, too. And then—and then, they smelled it. All of a sudden, a smell from a thousand flowers in full bloom enveloped the ship. And the little queen’s diamond heart became light and happy. The black ship seemed to recede in the distance.

“When they were very close to the island, it started snowing. The lighthouse keeper had lit a pipe, but now the pipe wasn’t working anymore.

“‘It’s clogged with snowflakes …’ he said. ‘No, wait a second! It’s clogged with rose petals! It’s snowing rose petals!’

“He was right. They weren’t snowflakes falling onto the planks of the green ship but the fragile petals of a thousand roses—white, red, and pink. Soon they covered the whole deck, and the little queen walked over a soft carpet of them to clear the ropes.

“‘Little queen,’ the sea lion said, emerging from a wave, on which floated white petals instead of white foam. ‘Are you sure you want to go ashore here?’

“‘Of course!’ the little queen exclaimed. ‘Look how beautiful the island is! It’s full of rosebushes, and they are all in bloom! This island is much more beautiful than my small island!’

“The sea lion sighed. The little queen put Mrs. Margaret into her pocket, and she and the lighthouse keeper walked down the pier—a pier made of rosewood that led to a white beach. Behind them, the silver-gray dog with the golden eyes came out of the sea and shook the water from its fur. Then it sniffed the ground, gave three loud and angry barks, and returned to the sea.

“‘Seems he doesn’t like it here,’ the lighthouse keeper said.

“‘But I like it a lot!’ said the little queen, walking up the path on the other side of the beach with her bare feet. She passed under an arch of red roses, and the lighthouse keeper followed, smoking his unclogged pipe thoughtfully. Behind the arch made of roses, a group of people waited for them.

“‘Welcome to Rose Island,’ one of them said.

“‘We don’t get many visitors,’ another one added. ‘Who are you?’

“‘I am the little cliff queen,’ the little cliff queen said, ‘but my kingdom—or was it a queendom?—has sunk into the sea. This here, in my pocket, is Mrs. Margaret, but there isn’t a Mr. Margaret, and this is the lighthouse keeper, but his lighthouse no longer has light. And who are you?’

“‘We are the rose people,’ the rose people replied, and, actually, that was quite obvious. For all of them—men, women, and children—were clad in nothing but blossoming roses. Their skin was fair and their cheeks were a little rosy, too, and their hair was dark like the branches of the rosebushes. Their eyes were friendly, and they had dreamy expressions.

“‘Come on, you must be hungry,’ a rose girl said, and the rose people led the little queen farther inland, till they reached a small pavilion filled with rosebushes. Inside, there was a big table, and on the table the rose people had laid out butter and bread, rose-petal jam, and tea made from rose hips.

“‘Oh, how very, very nice!’ the little queen exclaimed, pressing Mrs. Margaret so hard to her chest that the doll’s face became wrinkled. The lighthouse keeper sat down at one of the chairs but quickly jumped up again. ‘They’re prickly!’

“The rose people were very sorry about that. They themselves didn’t feel the thorns. They covered the chairs with white cushions filled with petals, which worked well. But after she had eaten enough bread with rose-petal jam and drunk enough tea, the little queen suddenly realized that her feet were hurting. The lighthouse keeper was wearing shoes, but she had walked to the pavilion barefoot. Now that she looked at the soles of her feet, she saw that they were covered with little red, burning dots.

“‘Oh no,’ said the rose girl who had spoken to them before. ‘Those are from the thorns on the path! Sometimes the bushes stretch out their arms over the ground and onto the paths … one doesn’t see them under the fallen petals …’

“And the rose people fetched a pair of wonderful white boots made of many layers of white silk for the little queen. ‘That’s silk from the rose caterpillar,’ the rose girl explained.

“‘Such beautiful boots,’ the little queen said. ‘I’ve never seen such beautiful boots.’ Which was true, for she hadn’t seen any boots until then, not in her whole life.

“After a while, the rose people left to get on with their work, cutting bushes, binding up branches, watering. Only the rose girl stayed with the little queen and the lighthouse keeper. She showed them around the whole island—showed them the rosewood houses and the lake, in which you bathed in rose petals instead of water.

“‘It’s a little boring, you see,’ she said. ‘Roses everywhere and nothing else. I’m happy you have come. Some change at last!’

“‘I wish I could stay,’ the little queen said, ‘but I can’t. The hunters on their black ship will come, and they will find me here between the rosebushes, no matter how deep I burrow in the leaves.’

“‘But they can’t,’ the rose girl said. ‘Just climb up that ladder to the lookout, little queen, and you’ll see the black ship. It’s anchored out there, far offshore. It can’t come any closer. The scent of the roses keeps it away.’

“So the little queen climbed the ladder—the lighthouse keeper helped her up the wooden rungs—and she saw the black ship anchored far away. But she also saw something else. She saw a dark, narrow rowboat approaching the white beach, a boat in which a man with dark clothes was sitting, all alone. He gazed at the rose island with longing in his eyes, but he couldn’t manage to get his boat any closer than it already was.

“‘There is somebody,’ the little queen said, ‘who needs my help.’

“And she climbed down the ladder and ran over the island, down to the beach, as fast as she could. For she had a good heart, a heart made of diamond. When she stood on the white beach, she saw that the rowboat was delicately decorated: there were flowers carved into the dark wood, and the stern had a golden tip. Strange, the little queen thought, how the beautiful boat didn’t fit with the old sweater and fleece-lined vest of the man who was rowing it.

“‘Can I help you?’ the little queen shouted. ‘Surely the two of us can pull the boat ashore!’

“‘I don’t think so,’ the man replied sadly. ‘This island holds something against me and my rowboat. It’s as if the current wants to keep us from getting any closer … I guess I have to be content just to sit here and look at the island.’ Suddenly, he sighed. ‘It would be much nicer, though, if I had someone to sit with me.’

“‘I’ll sit with you for a little while!’ the little queen said and started wading out into the water. ‘Take me with you, as you row along the shore!’

“‘Oh yes, come with me!’ the man said happily. And he helped the little queen into the boat.

“‘Sit here on this bench …’ He stroked his blond mustache and rolled up his sleeves, and then he started rowing. The boat shot forward like an arrow, but it also seemed to move away from the shore. ‘That’s the current,’ the man said. ‘It wants to push us away …’

“‘Little queen!’ someone shouted from the beach. ‘Little cliff queen!’ It was the lighthouse keeper—and the rose girl. They were standing on the beach, waving.

“‘Wait!’ the little queen said. ‘Maybe they want to come with us.’

“The man shook his head. ‘No,’ he said in a quiet voice, ‘I think it’s much nicer with just the two of us. They’d only disturb us.’

“‘Jump out, little queen!’ the rose girl shouted, and the lighthouse keeper shouted, ‘Come back!’

“‘She’s my passenger now!’ the man shouted back. ‘You don’t have any say in the matter!’

“The little queen saw the rose girl take a deep breath before the girl shouted, even louder than she had shouted before, ‘Do you remember what the white mare told you?’

“‘The white mare?’ The little queen thought about that. ‘She said that I must run … as fast as I can … to the highest cliff … and if I meet a man wearing my name …’ The man still had his sleeves rolled up and, suddenly, the little queen saw the tattoo on his right bicep. When he saw where she was looking, he quickly pulled the sleeve down, but she had already read the letters there. And her heart turned ice-cold from fear. ‘Who are you?’ she asked the man.

“‘You can call me father,’ the man said.

“‘I’ve got to go now,’ the little queen said, and then she jumped overboard and started swimming toward the shore. But the water was as ice-cold as her heart. Even colder. The waves, she thought, are beautiful, but they are dangerous … They will devour me … Then she felt somebody lift her out of the water and carry her to the beach. It was the rose girl. The roses that she wore seemed to fend off the cold and protect her slender body. She put the little queen down on the beach, and the lighthouse keeper shook his head and pointed at the rowboat. The man in it was removing his fleece-lined vest and his old sweater; underneath he wore a red gown. A diamond was embroidered onto the sleeve of the blood-red material in exactly the same place the man had his tattoo—a tattoo of the little queen’s name.

“He turned his boat and slid away, without a sound, toward a dark shadow in the water beyond, back to where he’d come from. Toward the black ship with its black sails.

“‘Oh, let’s stay here!’ the little queen cried. ‘This is the only place where I am safe from him and the other hunters on the ship!’

“‘If you really want to stay,’ the rose girl said, ‘take this necklace.’ And she put a garland of fresh, blooming roses over the little queen’s head. When the little queen turned her head, the thorns of the stems cut into her skin, and a trickle of blood ran down her neck and dyed the artificial fur collar of her jacket red. And the little queen was afraid.

“‘I worried this would happen,’ the rose girl sighed as she took the necklace away. ‘Go back to your own ship, little queen. Only the rose people can live on Rose Island.’

“She accompanied the little queen and the lighthouse keeper back to the pier, and the lighthouse keeper, from sheer nervousness, was already smoking his third pipe.

“‘Rose girl … how did you know what the white mare said to me?’ the little queen asked.

“‘When your island sank, the wind carried her words over the sea,’ the rose girl answered. ‘The others didn’t hear them, but I did. I heard the breaking of the trees, the bursting of the rocks, and the last words of your white mare. And I knew you were in danger, and I was worried about you even then, though I didn’t know you. But now I know you. And now, I’m even more worried.’

“The rose girl laid her pale hands on the little queen’s shoulders, and the two looked at each other for a long time. On the rose girl’s nose there were five tiny freckles, which distinguished her from the other rose people.

“‘I am fed up with seeing nothing but roses, day after day,’ she whispered. ‘Can’t I sail with you and take care of you, little queen?’

“‘You can,’ the little queen said, ‘but I don’t know what will happen to us. Maybe we will die out there on the blue sea.’

“‘Maybe,’ the rose girl said, smiling.

“The lighthouse keeper helped the rose girl aboard. The little queen helped Mrs. Margaret, who was a little vain and had donned a rose petal for a hat. But all of a sudden, the silver-gray dog was standing on the pier barking. He jumped over the green railing of the ship, bared his teeth, and ripped the branches from the rose girl’s arm, and the roses covering that arm withered instantly.

“‘What are you doing?’ the little queen shouted angrily. ‘She has just saved me! The hunter with the red gown wanted to take me away in his rowboat, but she took me back to the shore! You just didn’t see it because you were here, on this side of the island …’

“The silver-gray dog dove back into the water with an angry snarl and disappeared. The green ship sailed on, though, and the little queen worried that maybe she would never see the sea lion or the dog again. And she felt a prick of pain in her diamond heart.

“But in the morning, there was a bouquet of white sea roses next to the bed in the cabin, where the rose girl had slept. They were the kind of sea roses that grow only far out in the sea and only in winter. Somebody must have plucked them from the froth on the waves. Possibly a sea lion. The rose girl smiled. But there, behind the green ship, were black sails, very close, much too close, and the little queen was cold in spite of her down jacket.”

Abel looked down into his cup. He drank the last bit of hot chocolate, which was long cold. He gazed out at the sea in the February dusk. Silently. Maybe he had used up all his words. Micha tore a little corner from the paper napkin and put it on Mrs. Margaret’s head, like a white rose petal.

“I think I … I’ll be back,” Anna said and got up. “Too much tea. Rose-hip tea …”

Anna was alone in the tiny room that led to the ladies’ room. She stood in front of the mirror, combed her dark hair behind her ears with her fingers, and leaned forward, over the marble counter with the two built-in sinks, so far that the tip of her nose nearly touched the tip of her reflection’s nose.

It was true. She had five tiny freckles there. You couldn’t see them unless you were really close. She took a deep breath and splashed her face with cold water. “Thank you,” she finally whispered. “Thank you for the sea roses. It doesn’t matter that you destroyed the roses on my arm with your teeth. They were unnecessary anyway.” And then she smiled at her mirror image. It seemed beautiful all of a sudden.

Abel and Micha weren’t talking about the story when Anna returned to the table. They were talking about school, Micha’s school, and about a picture she had painted there. And about Micha’s teacher with the blond curls: Mrs. Milowicz, whose name Micha never managed to spell correctly and who’d been wanting to talk to Micha’s mother for a long time now.

“She can talk to you instead, can’t she?” Micha said, shrugging. “I told her that. Like she did on the first day of school, back then.”

“Yes,” Abel answered, but he looked away, out at the sea.

“Didn’t your mother come on that first day?” Anna asked, and then was immediately sorry that she’d asked.

“Mama doesn’t like school,” Micha said to Anna. “She always has other things to do. And sometimes she has to sleep in really late in the morning, if she’s been out the night before. Abel, what I wanted to tell you before was we had to draw a fish, and I made one with a whole lot of colorful scales, and you know what I can write now? X. Even though you never need it. It’s strange what you learn in school, isn’t it?”