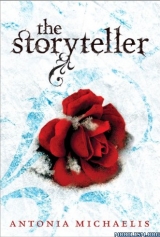

Текст книги "The Storyteller"

Автор книги: Antonia Michaelis

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

That was Anna’s chance. All she had to do was to step forward, to snatch the gun. She didn’t. She stayed where she was.

“I hate them,” Abel said, his face still behind his hands. “I hate all of them. Every single guy.”

He looked at her again, picked up the gun. Chance squandered, Anna Leemann.

“I thought Marinke was someone I could offer a deal to,” he said. “I followed him … Jesus. I mean, who goes for a walk on the beach in Eldena at night? It was as if he wanted something to happen. Maybe he was looking for adventure, something different from his life at the office. There he was, with his leather jacket and his I-understand-you, you-can-call-me-Sören look … he looked so gay. But I was mistaken. I offered to go with him, to do it for free, to do whatever he wanted, if he’d just forget about Micha and Michelle. I misjudged him. He gave me a look of contempt, spat out in front of me. So this is how it is, he said. Forget it, boy, and while we’re talking about fucking … what about your sister? Am I wrong, or do you love her a little too much? That’s when I decided he had to die. He really believed that. That I would do that to Micha. It was easier the second time. Like it was with the other thing. The inhibition threshold drops. If you shoot one person, the second one is a game. He was a coward, by the way. He turned voluntarily …” He shook his head. “No, that’s not true. That’s a lie. It wasn’t easier.”

He rolled up his left sleeve. Anna counted three circular scars next to the long one. One more than last time.

“One for each of them,” Abel whispered. “These are scars of pity. I had to do something afterward. Something I’d feel … maybe not even out of pity but more for me, so I’d know I still exist in spite of everything … ridiculous, isn’t it? Like a child pounding its head against a wall. This is Lierski. And Marinke. And that is Knaake.”

“Knaake,” Anna repeated, her voice flat. “Why, Abel? Why did you do that?”

“He was finding out stuff,” he replied. “He was following me. I told you that. He took a step back, onto the ice in the shipping channel, to escape the bullet that I hadn’t even shot. I saw him fall through the ice … I called the fire department from a pay phone—it was the only number I could think of to call. I suddenly felt I just couldn’t do this anymore. I didn’t want him to die. He was a traitor, but I liked him. I … I really hope he makes it … I wish …”

For a moment, it was silent, the silence echoing and reechoing from the tiled walls of the bathroom, like the pain and fear of a small boy a long time ago.

“Bertil?” Anna asked.

“What about Bertil?”

“Is he still alive?”

“Of course he’s alive. Why would I do anything to Bertil?”

“After what he did yesterday …”

“You don’t get it, Anna. This is not about me. It’s about Micha. Bertil’s a different story. He’s never been any threat to Micha. If he’d started figuring out the truth about the murders … then, well … but he wasn’t even interested. He was only interested in this other thing, and that he figured out—as the whole school knows. I was stupid to talk to him. But I’m tired, Anna. I’ve had it.”

“And … Michelle?”

“Michelle. Michelle. Everything started with her.”

“But there’s no scar on your arm for Michelle. Or is she the long one? But that one came later, didn’t it …?”

“The long scar,” Abel said and smiled again, “that’s you, Anna. What happened in the boathouse was worse than anything else. I did to you what Lierski did to me. I didn’t want to. I just … how do you say it? I just lost control. It happens. Some things are just too much. But I don’t have a scar for Michelle because I didn’t kill her. That’s simple.”

“You didn’t? Then who did?”

He stood up without letting go of the gun. He stood in front of her and looked down at her … he was taller than she was. “There was so much blood,” he said. “Blood everywhere. On my hands, on her hands, on my shirt, her face, on the tiles, smeared in streaks, on the small round blue carpet … I threw it away later, that carpet … I hadn’t known that blood was that red, that light red: big, fallen, burst droplets of blood … the color of poppies. A sea of blood, a red endless sea, purple waves, carmine froth, splashing color … I remember that I thought all of this back then. Micha was still sleeping. I was the one who found Michelle.

“She’d slit her wrists … long, deep cuts in both arms … she’d wanted to make sure. Blind white cat. Self-centered beast. She never thought of us, not for one minute. She ran away from her own problems, her fucked-up life … the wrong guys, booze, unemployment, drugs. We have an old bike trailer in the basement … we used it to transport furniture and stuff we found in the trash … I put her into the bike trailer and took her to the Elisenhain. She loved the anemones so much. We used to go for walks there when I was little, before Rainer Lierski … I was sure someone would see me, stop me. I almost wanted somebody to. But nobody did. That was the day the island sank, and the sea was red.”

He fell silent. He lifted the gun and put it in his pocket.

“You really thought that I did it, didn’t you?” he whispered. “That I shot my mother? That I’d shoot you?”

“What are we going to do now?” Anna whispered.

“I don’t know. You tell me. Everything’s ending.”

“No!” she whispered. “No. Not for me. Everything’s just beginning. We’re seventeen.”

She put her arms around him and hugged him as tightly as she could.

“Are you trying to tell me that you’ll stay? In spite of everything?” he whispered. “Anna, I’m a murderer. I’m a murderer and a hustler and a dealer. I’m everything that’s unthinkable in your world.”

“I am not staying with the murderer,” she said, her words muffled by his jacket. “I am not staying with the victim Abel Tannatek or the culprit Abel Tannatek. I am staying with the storyteller.”

She pulled him out of the bathroom, into the living room. She pulled him down on the sofa. She realized that she was crying again. She couldn’t help it. She didn’t know who started to kiss whom, but it was a desperate kiss, a kiss in front of the sharp edge where the ice had broken and the water was rushing by in an unpassable stream, separating them from the mainland.

“We’ll find a solution,” Anna whispered. “There is one. There must be one.”

But first, something else seemed more important, and it happened as if it had to happen. The most improbable of all the things that could have happened. Maybe it happened because there was nothing standing between them anymore—no more secrets, no more lies, no mistrust, nothing. The torn, invisible cloak of pain was enveloping them both as it had done in that night in the house where the air was too blue. Anna felt Abel’s hands under her T-shirt, careful, timid, hesitating, and she didn’t force these hands to do anything this time. She gave them time. She thought about the white sails on the deck of the green ship whose name they’d only found out late in the story.

Everything was different from the dream. Much more complicated. Much more real.

She tried to get out of her clothes, got all tangled up in them, and laughed. And that, she knew, was all unreasonable Anna, as reasonable Anna had never done any of this. Reasonable Anna had left for good. Finally, they were sitting on the sofa naked, the two of them. She was on his lap, and she really, really did hope that Micha was sleeping. And this, she thought, was the moment to say something about a condom, but she didn’t … the inhibition threshold had dropped. K IS EacH Oth ER, she thought … letters on a window … she let her hands wander down, and she guided him, and it was surprisingly easy now … it was a gliding movement like skating over the ice … everything was easy … there was no pain … there was a rhythm they both shared, and she was leading … it was different from dancing, when the man leads the woman. She led his fingers to the right spot. And with her eyes closed, she saw the color green, not blue like his frozen eyes, but green … green like the ocean beneath the ice. She hadn’t known sex had a color. The color created waves … foaming, frothing, whirling up, and everything was good, everything was right, and maybe, Anna thought, this color would cover everything else—the not-good, not-right things that had happened. The pain held in the tiles of a bathroom. The running footsteps in a boathouse. Bertil’s announcement and its contents, the frantic fear that the same could happen to Micha. The wave of green, ocean color would break … right now, she could feel it …

“Anna,” said Abel. She opened her eyes and looked at him, frozen in her movement.

“If something … if I can’t be here anymore,” he whispered, and Anna thought of the cold walls of court buildings and penal institutions and didn’t want to think further, not now. “If I can’t be here anymore … what will happen to Micha? She seems to love your mother …”

“My parents would adopt her,” Anna said. “On the spot.”

He nodded and closed his eyes, and she closed her eyes again, too, and seconds later, the green wave broke and washed over them. Not exactly at the same time—exactly at the same time is always a lie—but the waves of the ocean in which they swam together followed one after the other. They stayed like this for a long time, sitting there, breathing each other’s breath, in and out. They kept each other warm in the last cold of the winter. There was a solution, Anna thought again, a way out … if this became possible, then everything else was, too.

“Of course,” Abel whispered. “Of course, there’s a way out. I know it now.”

And she wondered if he could feel her thoughts through her skin.

I am completely happy, she thought, hoping that he would feel this thought, too. At this moment, I’m completely happy, isn’t that strange? Actually, it isn’t strange at all. Ah, linger on, thou art so fair.

A car stopped in front of the house; they heard the engine and then voices, those of Mrs. Ketow and several men … hurried voices. There was something sharp in their voices, something dangerous—the edge of the ice and a raging current.

They stood up and went over to the window, still naked.

“Shit,” Abel said in a low voice, “I didn’t think they’d be that quick.”

Two cars were parked in front of the house. One belonged to Magnus, the other to the police … a green and white police car, Anna thought—the ocean riders. Everything in Abel’s fairy tale made sense.

She’d never gotten into her clothes faster. Everything was happening too fast now.

Abel hugged her again, for a very short moment. “There is a way out,” he repeated, and she didn’t understand … she understood nothing. She ran after him, into the hall … Micha emerged from her room with sleepy eyes, the book about the dog in her hand. She saw Abel rush out of the apartment … he didn’t turn back to look at Micha. There were policemen on the stairs, she could hear their steps … maybe someone shouted something, shouted for her to stand still, stay where she was … for Abel to stand still.

She stood by the front door, pressing Micha against her with one arm. Abel wasn’t running down the stairs, he was running up the stairs … the stairs leading to the door of the attic that no one ever used. There was a narrow landing in front of the attic door, where Abel came to a halt.

Out of the corner of her eyes, Anna registered other people on the stairs behind the policemen: her parents … and Bertil. She didn’t look down at them, she looked up at Abel. The policemen had stopped on the fourth-floor landing, where Anna and Micha were standing. They were looking up as well.

“Abel Tannatek?” one of them called.

“Yes,” said Abel very calmly. “Yes, that is me.”

“Get down here,” the policeman said. “We’re here to arrest you for murder. Everything you say from now on …”

“My God,” Abel said with half smile, “you actually say that in real life?”

He looked at Micha. And then he looked at Anna. She saw that he was holding the gun. She heard the release of the safety catch.

“Anna,” he said. And he lifted the weapon and took aim.

She was too surprised to react.

Or, maybe she wasn’t surprised at all.

She didn’t hear the shot. The world became strangely silent. That was how she saw the storyteller for the last time—in an absolutely silent world, in a staircase. He’d hit his target.

When she fell into darkness, she knew that she would never see him again.

She’d loved him to the very end.

“THEY STOOD AT THE EDGE OF THE ICE, YOU KNOW, and looked over at the mainland. It was so close and yet so far away that they could never reach it. And behind them, the cutter came closer and closer. They could hear her golden skates scratching over the ice.

“‘So I will drown,’ the little queen said. She jumped into the ice-cold water headfirst, and the blind white cat, whose absolute blindness several people had begun to doubt, shook her head. ‘Tz-tz-tz,’ the cat hissed, and then she rolled into a ball on the ice and fell asleep. The asking man and the answering man put their hands in front of each other’s faces so as not to see the little queen drown.

“Only the rose girl acted. She jumped into the water after the little queen, without thinking twice.

“She found her hand in the roaring stream, a small, helpless, royal hand, and they clung to each other. But they couldn’t swim against the current. It was much too strong, and the water was much too icy. And then they felt something pulling them; there was something pulling them against the current. The rose girl managed to lift her head out of the water and saw the sea lion’s head next to them. He had sunk his teeth into the little queen’s sleeve and was swimming against the stream. And suddenly, she could feel herself moving toward the shore. The rose girl saw the sea lion fighting the water. He needed all his strength to pull her and the little queen along. He was a strong swimmer, but the current was stronger. She tried to help him, tried to swim by herself, but he shook his head. ‘Hold still,’ his golden eyes begged. ‘It’s easier if you’re still. You can’t help me.’

“So she held still, and the little queen held still as well, and the cutter stood on the ice, watching them. She lifted her hand and made a barely perceptible movement, and the little queen and the rose girl both knew that the movement was a signal, that she was calling someone—the ocean riders. The ocean riders on their seagrass-green and snow-white horses, who would come to restore the order they believed to be justified.

“The current tugged at the three, trying to drag them away. It hit them and bit them and drooled on them greedily, but in the end they reached the shore. With the last of his strength, the sea lion crept onto the beach, and there he lay, limp and motionless. The rose girl got up and started patting him, to bring life back into his body; and the little queen laid her hand on his neck, so that he knew she was there and that he’d managed to get her onto land safely.

“When she did this, he lifted his head.

“And on the other side of the stream, the ocean riders dashed over the ice. At its edge, they stopped their horses, who reared and whinnied. Maybe it wasn’t true. Maybe it was only a rumor that the ocean riders could gallop over the water. Or maybe the current was just too strong here, even for them.

“The cutter pointed at the little group on the mainland. ‘Do you see the sea lion?’ they heard her say. ‘He took them over there, the silver-gray sea lion with the blue eyes.’

“The rose girl looked into his eyes. They weren’t golden anymore; they’d frozen to blue ice. At this moment, one of the ocean riders lifted his rifle—they all carried hunting rifles—and a shot rang out over the water. With the sound came a bullet, and that bullet hit the sea lion between the eyes.

“‘No!’ the little queen screamed, and she jumped up. Before the next shooter could fire his deadly rifle, tears sprang from her eyes and fell down into the stream, flooding it. And it became so warm that the rest of the ocean warmed up in milliseconds. For someone who has a diamond for a heart also has tears that are as warm as the sun. The ice melted in an instant, and the ocean riders sank into the sea, together with the cutter. Then the current carried them away, along with the asking man and the answering man and the sleeping white cat and the lighthouse keeper, who had still been lying somewhere on the ice.

“The little queen and the rose girl watched them drift away. They would never find out what happened to them in the end.

“Finally, they turned and started to walk away from the sea. The rose girl had lifted the sea lion up and was carrying him with her. But he wasn’t a sea lion anymore.

“He had changed into a human being.

“‘He saved me,’ the little queen said.

“‘He saved us,’ the rose girl said.

“‘But he lost himself in the process,’ said the little queen. ‘He will never know that he saved us. And I will cry. I don’t cry now because all of my tears have fallen into the ocean. There will be more tears, though, growing inside me, and I will cry them all my life. I still don’t know what death means, but my sea lion knows it now …’

“‘Don’t cry,’ the rose girl begged. ‘Don’t cry all your life, little queen. He does know that he saved us. He will stay with us. As a memory. Do you see the house up there on the cliff?’

“The little queen swallowed the tears that had already started to grow back. ‘Yes,’ she replied. ‘I see it. It’s beautiful. There are roses in the garden, and someone is feeding the robins.’

“‘Do you hear the music spilling from the windows as well?’ the rose girl asked. ‘Piano and flute. You could live there. You could live in that house and play music instead of crying.’

“And the little queen nodded.”

“And that’s the end of the fairy tale?” Micha asked.

“That’s the end of the fairy tale.”

“No,” Micha said and stood up. “No, that’s not the end. Because, you know, the little queen decided something else. She didn’t want that diamond heart anymore. She exchanged it for a normal heart. The diamond heart she put on the sea lion’s grave.”

“That was a very good idea.”

“So … did it end well, in some ways?”

“Yes, it did … in some ways. It was the sea lion’s greatest wish that the little queen would reach the mainland. And his wish was fulfilled, and, I think, in the end he was happy.”

She stood up, too. They’d been sitting on folding chairs in the yard, watching the robins, but when Micha had jumped up, all the robins had flown away.

“I can hear the piano,” Micha said. “Linda’s playing. I think I’ll go in and help her. I have to think of something else now, quickly, otherwise …”

“Go ahead and help Linda with the piano,” Anna replied. “I’m going to stay here a little longer.”

She closed her eyes and saw the landing on the fifth floor again.

She couldn’t help it.

She saw Abel standing there. He smiled. She saw that he was holding the gun. She heard the release of the safety catch.

“Anna,” he said. And he lifted the weapon. It was then that she understood his way out and why he’d asked her what would become of Micha. He hadn’t wanted to leave like Michelle, not without taking care of everything first. He put the barrel of the gun into his mouth. He didn’t hesitate, not for one second. She didn’t hear the shot. The world became strangely silent, and she fell into a cold darkness, dark like the ocean deep … deep under the ice.

The darkness only lasted for seconds, maybe not even that long. She opened her eyes, and, up there on the landing, he wasn’t standing anymore. She looked down the stairs and saw that Linda had buried her face in her hands. She saw that Bertil wanted to come up the stairs, saw Magnus grab his arm and hold him back, his grip as firm as steel. None of the policemen moved. She thought she should have run. But she didn’t.

It was Micha who ran.

She freed herself from Anna’s arms and ran up the stairs, and Anna followed her, climbing the steps very slowly. She saw him lying there, saw the blood in which he lay, so incomprehensibly red, light red—big, burst droplets of blood the color of poppies. A sea of blood, a red endless sea, crimson waves, carmine froth, splashing color … Micha was kneeling next to his legs and had laid her arms and her head on his knees, where there was no blood. And she was singing, very, very softly.

Just a tiny little pain

,

Three days of heavy rain

,

Three days of sunlight

,

Everything will be all right

.

Just a tiny little pain …

And Anna asked herself, were the words running out of Abel’s head with the blood, all the words he’d wanted to weave into stories later … later, always later. Words that could have been written in summer by the sea … in Ludwigsburg, in a secret hiding place between the beach grass; or in a student apartment in some faraway city; or on a journey around the world. Shouldn’t she be saving the words somehow, collecting them? All the words … the words of the storyteller. She stood there very still, next to Micha, and it broke her heart to hear Micha sing. The place in her, though, where her tears should have come from, was rough and dry. No, she didn’t find any tears in herself to cry for the storyteller.

The storyteller didn’t exist anymore.

They buried him a week after the thirteenth of March. After his eighteenth birthday. Anna put a bouquet of anemones on his grave, a bouquet of spring. Linda held Micha’s hand the whole time, and Micha held Mrs. Margaret’s hand … Mrs. Margaret, in her blue-and-white-flower-patterned dress. Anna didn’t hold anybody’s hand. She walked next to Magnus in silence, without looking at him.

Micha’s uncle didn’t care where she lived. He signed all the necessary papers with a resigned shrug. So she would be adopted. Micha Tannatek would change into Micha Leemann. She’d reached the mainland as Abel had wanted her to. She would never go through what he’d gone through.

And still, Anna searched for tears inside herself.

Abel’s picture was on the wall above the chimney now, the one good photo Micha had found of him. She’d insisted they have it framed and hang it there, so Abel could see what she was doing all day long. So he would stay with them. And every time Anna passed that picture, she thought she’d find her tears. But they never came. She must have used them up while Abel was alive, for now that he was dead, there were none left. They had talked for the longest time, Magnus and Linda and her. Everybody knew everything now. Or did everybody know nothing? Nobody knew anything … Nobody could know everything.

Anna still played the flute, but she didn’t practice the pieces she should have practiced. Instead, she played the simple melodies of Leonard Cohen. She still didn’t know if she’d ever be able to ask Knaake about him. Or whether he would wake up again. Finals had become irrelevant. She’d decide later whether to take them … and when. Linda and Magnus didn’t press her. Maybe, Anna thought, she wouldn’t go to university. Maybe she’d do something different altogether. She just had to figure out what. She’d talk to Gitta about that when she felt ready.

Bertil called for a while, but Anna never answered, and finally she changed her number. She felt sorry for him, but she couldn’t help him.

Leonard Cohen sang from one of the scratched LPs,

Baby I’ve been here before

,

I know this room, I’ve walked this floor

I used to live alone before I knew you

I’ve seen your flag on the marble arch

But love is not some kind of victory march

No it’s a cold and a very broken Hallelujah

Hallelujah, Hallelujah …

Somewhere in a parallel world, things were different.

Somewhere in a parallel world, Abel hadn’t fired that last shot. Possibly, he hadn’t fired the one before it either, the one that killed Sören Marinke. And Knaake had never fallen through the ice over the shipping channel. And if these two things hadn’t happened … the last shot hadn’t. Somewhere in a parallel world, Abel was in prison, maybe for a long time … maybe he was in therapy … therapy that didn’t heal anything but brought some things in order. Time couldn’t change the past, but it brought peace. And parallel Anna … she waited.

She was waiting for him when he took his first step back into the normal world. She watched him walk toward her, a smile in his winter-ice eyes. She had long since grown up. They married on a February morning as clear as crystal. Micha was their only witness. They sent her postcards from their journey around the world … from the desert and several remote islands. Later, Micha often visited them, an adult Micha with a husband and two children. And in the house where Anna and Abel lived, somewhere at the end of a quiet, green lane, there were children as well. Laughing kids, badly behaved kids, dirty and loud kids, who ran through the yard, lighthearted. There were a lot of flowers in the garden, but no roses, and the only songbird to never stray there was the robin.

She told him about the garden when she visited his grave. He lay there, in the slowly stirring March earth, a piece of dead matter. But in their parallel world, they lived on, side by side. She developed each part of their parallel world in meticulous detail … the sunflowers in a vase, the late afternoon light coming in through a window, glasses he wore when he was older, a shelf full of books, a faded leather armchair.

Nothing was perfect, but everything was all right. The light was never just blue.

And the snow that fell onto the roof in winter … it fell softly … softly … and it covered the house, the armchair, the books, the children’s voices. It covered Anna and Abel, covered their parallel world, and everything was, finally, very, very quiet.