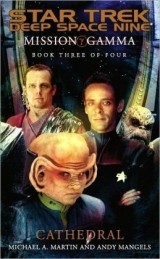

Текст книги "Cathedral "

Автор книги: Andy Mangels

Соавторы: Michael Martin

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

Bashir felt a tingle of apprehension, recalling a report he had read about a similar alien artifact once having seized control of the computers of Starfleet’s flagship.

“How about it, Nog?” he said. “Is it dangerous?”

Nog shook his head. “Nothing executable. Looks to me like it’s just a text file.”

The information abruptly stopped scrolling. Nog punched in a command that shunted the information into a protected memory buffer.

“A whopping hugetext file,” Ezri said. “Nearly eighty megaquads.”

“So what does it say?” Bashir said, his task at the subspace radio console all but forgotten.

Ezri’s expression was a study in fascination. “It could be the sum total of everything this civilization ever learned about science, technology, art, medicine…”

Nog shrugged. “Or it could be a compilation of their culture’s financial transactions.”

Bashir considered the unfamiliar lines and curlicues still visible on the screen. Before him was something that could be the Gamma Quadrant’s equivalent to the Bible or the Koran. Or an ancient municipal telephone directory.

“It could take lifetimes to puzzle it all out,” Dax whispered, apparently to everyone and no one. Bashir found the idea simultaneously exhilarating and heartbreaking.

Staring half a billion years backward into time, Ezri appeared awestruck, no longer the duranium-nerved commander she had been only moments before. Her current aspect struck Bashir as almost childlike.

“Let’s try running some of it through the universal translator,” Bashir said, intruding as gently as possible on Ezri’s scientific woolgathering. “We can probably decipher some of it by comparing it to language groups from other nearby sectors.”

After a moment Ezri nodded. “What he said, Nog,” she said finally, returning to apparent alertness.

An alarm klaxon abruptly shattered the moment. “Collision alert!” Nog shouted, as he manhandled the controls and threw the Saganhard over to port. Bashir had a vague feeling of spinning as he lost his footing, and his head came into blunt contact with the arm of one of the aft seats.

He struggled to his knees, shaking his head to clear it, holding onto the chair arm. He looked up at the main viewport.

The alien cathedral had suddenly sprouted an appendage. Or rather, a long arm, or tower, or spire had just rotated into normal space from whatever interdimensional realm served to hide most of the object’s tremendous bulk.

Though the spire couldn’t have been more than a few meters wide, it was easily tens of kilometers in length. It had no doubt been concealed within the unknowable depths of interdimensional space until that moment.

And it appeared to be rotating directly toward the Saganvery, very quickly. Bashir felt like a fly about to be swatted.

“Nog, evasive maneuvers!” Ezri shouted, her mantle of authority fully restored.

“Power drain’s suddenly gone off the scale, Captain,” Nog said, slamming a fist on the console in frustration. “The helm’s frozen.”

“Looks like we got a little momentum off the thrusters before the power drain increased,” Dax said calmly. “Maybe we’ll get out of this yet.”

Or maybe we’ll drift right into the flyswatter’s path.Bashir clambered into a seat immediately behind the cockpit and started to belt himself in. Then he stopped when the absurdity of the gesture struck him. We’re either getting out of this unscathed, or we’re going to be smashed to pieces.

He rose, crossed to the subspace transmitter, and tried to open a frequency to Defiant.

Only static answered him. He glanced across the cabin at Dax, who was shaking her head. “Subspace channels are jammed. Too much local interference from this thing.”

“Our comm signals must be going the same place as our power,” Nog said.

Into this thing’s interdimensional wake,Bashir thought.

“Brace for impact!” Dax shouted.

The lights dimmed again, then went out entirely, and a brief flash of brilliance followed. Bashir felt a curious pins-and-needles sensation, as though a battalion of Mordian butterflies was performing close-order drill maneuvers on his skin. Darkness returned, and seconds stretched lethargically into nearly half a minute.

Once again, the emergency circuits cast their dim, ruddy glow throughout the cabin. The forward viewport revealed the alien cathedral hanging serenely in the void, its spire no longer visible, its overall shape morphed into even wilder congeries of planes and angles.

Dax heaved a loud sigh. “Our residual momentum must have carried us clear. Couldn’t have missed us by much, though.”

Bashir couldn’t help but vent some relief of his own. “Thank you, Sir Isaac Newton.”

“Ship’s status, Nog?” Dax said.

“Most of our instruments are still down, but our power appears to be returning as we drift away from the object’s wake. We’ve already got some impulse power and at least a little bit of helm control. And the subspace channels are starting to clear up, too.”

For a moment, Bashir felt dizzy. He assumed either the inertial dampers or the gravity plating must have taken some damage.

“What just happened to us?” he said.

“My best guess is we passed right through the edge of the thing’s dimensional wake,” Nog said. “It’s a miracle we weren’t pulled into wherever it’s keeping most of its mass.”

Bashir had trouble tearing his gaze away from the starboard viewport and the weirdly graceful object that slowly turned in the distance. A miracle indeed. That something like this even exists is something of a miracle, I’d say.

For a moment he thought it was a pity that he didn’t believe in miracles.

A burst of static issued from the cockpit comm speakers, then resolved itself into a human voice. “…mei, come in,Sagan. This is Ensign Tenmei.Sagan, do you read?”

“Go ahead, Ensign,” Dax said, frowning. It was immediately obvious that something was wrong aboard the Defiant.

“I’m afraid we’re in need of Dr. Bashir’s services, Lieutenant,”said Tenmei.

“Is someone injured?” Bashir said over Ezri’s shoulder, the alien artifact suddenly forgotten.

“We have wounded aboard, but they’re not ours.”It was Commander Vaughn’s voice, deep and resonant. “They’re guests, and some of them are in pretty rough shape.”

Bashir wasn’t relieved very much by Vaughn’s qualification. Injured people were injured people, and he was a doctor. “Acknowledged, Captain,” he said as he watched Nog launch a subspace beacon.

Good idea. We’re going to need to find our way back here when we have more time.

Dax took the sluggish helm and gently applied power to the impulse engines. “We’re on our way, sir.”

“Too bad the Defiant’s not carrying an EMH,” Dax said to Bashir as they got under way.

“I far prefer flesh-and-blood help in my medical bay,” Bashir said. Strangely, he felt no urge to explain about the mutually antipathetic relationship he shared with Dr. Lewis Zimmerman, the inventor of the emergency medical holograms that were found on so many Starfleet ships these days. In fact, he found that he was no longer in the mood for conversation of any sort. As the alien cathedral dropped rapidly out of sight, he gathered his energies for the triage situation that he presumed lay ahead.

But the alien cathedral’s ever-changing shadow still moved very slowly across the backdrop of his thoughts.

5

Mirroring Yevir’s mood, the dusky sky was darkening, slowly eliding from lavender to a deep rose. The air crackled with the cool of late winter and the scent of nerakblossoms, a tantalizing hint of the coming spring. Ashalla’s city streetlights were already aglow, illuminating the paths of the many Bajorans who bustled to their shrines and homes.

An older woman stopped Vedek Yevir and began speaking to him. Her grandson was planning to marry next month, and she wanted to know if he would ask the Prophets to bless the union. Smiling, Yevir promised that he would do so at the main Ashalla temple on the following day. Shedding tears of gratitude, the woman thanked him and backed away.

Yevir noticed that other passersby on the concourse had in turn noticed him. Most of them nodded and smiled as they passed him, and he recognized most of their faces. He couldn’t help but wonder how many of them had read the accursed so-called prophecies of Ohalu—and how far the poison that Colonel Kira had released four months earlier had spread through the very heart of Bajor’s capital city. How many of these people hope that I will become kai? How many of them would prefer Vedek Solis instead?

His guts braiding themselves into knots of anxiety, Yevir continued walking, passing the bakery where he often bought pastries on his way to his office. The proprietor gave him a respectful wave. Yevir knew that the man would soon make his way to the evening temple services; he was exceedingly faithful. Still, it seemed odd that he hadn’t yet closed his shop for the evening, so close to the sounding of the first temple bells.

Ahead, Yevir saw several people gathered around the plaza’s public holovid kiosk. He stepped up to listen, in time to hear a newscaster discussing the day’s events with a political commentator.

“…the end of the second week since the peace talks stalled between Bajor’s representatives and Cardassia,”said the newscaster. “Do you see any progress in the initiative to resume the talks?”

Yevir recognized the commentator as Minister Belwan Ligin, an old-line conservative who had lost most of his family during the Occupation. Despite this, he had always struck Yevir as remarkably fair and evenhanded in his judgments about the Cardassians. “I don’t believe that any direct progress has been made, but certainly Minister Asarem and the others are going to begin feeling real pressure soon. With Bajor’s entry into the Federation imminent, it seems to me that a viable peace agreement would be in both peoples’ best interests. But Asarem has proven to be quite astute in the past when dealing with potential crises, so perhaps…”

Yevir walked away from the kiosk, shifting his bag over his shoulder. Perhaps he ought to schedule a meeting with Asarem, or even First Minister Shakaar Edon, to discuss how best to get the talks restarted. Either of them would probably welcome a fresh perspective on the matter. Surely they could be persuaded that reaching a mutually favorable denouement now—before the Federation relieved Bajor of all such responsibilities—was the only way to create a lasting peace with Cardassia. And it certainly wouldn’t hurt his chances of becoming the next kai if he were to help broker such a resolution.

But how?

As he entered the four-story, stackstone-fronted building that housed his offices, Yevir saw many of the lower-level staff members preparing to leave for the evening. He greeted each of them by name, wishing them all an uplifting temple service. Yevir’s assistant stood up from behind a desk as he rounded the corner toward his office.

“Vedek Yevir. How blessed to see you,” Harana Flin said, and he knew she meant it. Harana indicated a young woman who sat in a corner chair. “She’s been waiting to see you for some time now. I told her I wasn’t sure when you would return this evening, but she insisted on staying.”

“It’s all right, Flin,” Yevir said, using the woman’s familiar name. He placed a hand on her shoulder and smiled gently at her. “I will be happy to see her. Thank you for your diligence. Now you’d best hurry or you’ll miss first bells.”

Harana gathered a wrap around her shoulders and let herself out as Yevir turned toward the waiting woman. She was very pretty, with high cheekbones and delicately oval eyes. Her hair was braided, encircling the top of her head in the helepstyle he knew was popular among the university crowd in Musilla Province these days. She was dressed in light blue robes that flattered her pale skin, and she held a young child whom she was clearly suckling beneath the robes.

“Hello, child,” Yevir said, smiling. “Won’t you come into my office?” He stepped ahead of her, opening the door. He expected her to be shy, in the manner of most supplicants who came calling. But she walked confidently, her head held high.

He entered the office after her, and as she sat on a chaise nearby, he set his shoulder bag on the desktop. He pulled out several books, placing them on top of a pile of documents that he kept neatly stacked in his work area. Next, he withdrew the small gold-and-amber jevonite figurine that Kasidy Yates, the wife of the Emissary, had given him more than two weeks earlier. He set the translucent statue at the top of the stack before turning his attention back to his visitor.

“You seem familiar, child. Have we met before?”

The young woman stared at him for a moment, though he could glean nothing of her thoughts from her eyes. She smiled slightly as she spoke, expressing neither shyness nor shame. “No, Vedek Yevir, we have not met. At least not officially. But you may know my face from the files that the Vedek Assembly very likely keeps on people like me.”

What an odd thing to say.Yevir’s curiosity was piqued. “I’m not sure I understand.”

“My name is Mika. Cerin Mika. I was once a member of the Pah-wraith cult.”

Yevir nodded, at last recognizing her more fully. “Yes, I remember you now.” Cerin Mika—or simply Mika, as she had told interviewers she preferred to be addressed—had been one of the few dozen cultists who had resided briefly on Empok Nor, during Gul Dukat’s tenure as their leader. Dukat had impregnated her, and after she had given birth to his child, had nearly succeeded in murdering her. If not for the intervention of Kira Nerys, Mika’s child would never have known its mother.

In the year and a half since that time, Mika had become a minor celebrity, as well as a figure of some controversy. The Bajoran people had been quick to forgive the woman, blaming Dukat for victimizing yet another innocent, spiritually minded Bajoran. Despite Dukat’s betrayal—or perhaps because her babe was half Bajoran and half Cardassian—Mika and her husband, Benyan, had become vocal advocates for peace between Bajor and Cardassia. They spoke publicly, and recently had begun lobbying certain ministers on a fairly regular basis.

“What can I do for you?” Yevir asked, though he was already fairly certain he knew what was on her mind.

“I will come straight to the point,” she said, reaching within her robes to detach the child from her breast. “I am the niece of Vedek Solis Tendren.”

Yevir’s brow furrowed as he realized that she had reasons other than a common doctrinal outlook to support Yevir’s chief rival for the kaiship. Vedek Solis had made it clear that he sought Bajor’s top religious leadership position—and that he did so at the behest of a newly formed sect which taught that Ohalu’s heresies were the True Way of the Prophets.

As intrigued as he was suspicious, Yevir said, “I must confess that I’m at something of a loss as to what I can do for you.”

Her smile persisted. “It may well be that I can do something for you,Vedek Yevir. I trust you’re aware of the details of my past association with the Pah-wraith sect. It wasn’t the first time I’d explored alternative religions.”

“And I trust that your experiences with Gul Dukat have taught you the error of your ways.”

She laughed at that, a pleasant, crystalline sound. “I have never been completely…satisfied with the orthodox teachings of Bajor, despite my uncle’s best efforts to put me ‘back on the right path.’ My sojourn with Dukat hasn’t changed that.”

Yevir shook his head slowly. “Forgive me, child. But I can’t help but think that Dukat’s attempt on your life couldn’t have been a clearer sign from the Prophets that it was a mistake for you to stray from Their wisdom. Unless, of course, you no longer believe in it.”

It was Mika’s turn to shake her head. “I havefaith, Vedek Yevir. Faith in something beyondme and my life. Faith that there’s something larger out there. But I’ve become less certain than ever that this something has anything to do with the so-called Prophets.”

Mika’s sudden irreverence grated on Yevir, though he’d certainly heard such talk many times before. During the dark days of the Cardassian Occupation, and sometimes afterward during his stint in the Bajoran Militia, he’d sometimes heard battle-scarred veterans and anguished civilians question the beneficence of the Prophets. It was to be expected. Now that he served his people as an instrument of the Prophets’ plan for Bajor, Yevir saw it as his sacred obligation to help all such suffering souls come to understand that the Prophets were the true source of all hope. He owed it to all whose paghwas in tumult, to all who stumbled in darkness.

Even those who were bent on turning a dangerously heretical vedek into Bajor’s next kai.

Mika continued, “A few months ago, my husband and I were made aware of the transmission of the prophecies of Ohalu onto the comnet. We read them and started talking to others who had read them as well.”

Yevir tried to keep his upper lip from curling in distaste, without perfect success. “It’s a shame that Ohalu’s heresies have replaced the true Words of the Prophets in the minds of so many misguided souls.”

“Ohalu’s writings didn’t replacethe teachings we all grew up with. They merely supplementedthem. They—”

“That isn’t so, child,” Yevir interrupted her. “Ohalu argues that the Prophets are not our spiritual guides, but are instead merely powerful, enigmatic beings whom we mistakenly worship. His so-called ‘prophecies’ undermine the very basis of our society. Without our divine Prophets, what are we? Where did we come from? Where will we go?”

She looked at him pointedly. “Since you and several of the other vedeks have already publicly supported the questioning of the old ways, I’m surprised to find your attitude toward Ohalu so inflexible. You haveread his work, haven’t you?”

He replied with a curt nod, then said, “Yes, though it pained me to see the verities of the Prophets twisted so.”

“Then you must know how many of Ohalu’s prophecies have come true,” she said resolutely. “The words he wrote millennia ago have become ourreality. It is not some vague future he foresaw, but our lives, our present.”

Mika had placed her finger directly on a raw nerve. Yevir had already sought—to little avail—the guidance of several Orbs on one burning question: Why are so many of Ohalu’s accursed prophecies so accurate?

He knew well that Bajor’s major orthodox religious writings abounded with prophecies, some vague and general, others more specific. But many legitimate prophecies had to be justified, interpreted, clarified,to bring them into line with current events. Why did it seem that noneof Ohalu’s prophecies required such clarification? Ohalu’s predictions had so far proven to be uncannily accurate. But if the heretical prophecies were true as a whole, then everything the Bajoran religion was built upon stood revealed as a lie; the Prophets could not, therefore, be Bajor’s protectors, but rather were merely an alien species who studied his people like so many bugs under glass, and occasionally deigned to aid them.

Yevir could not reconcile this. In his heart, he knewthe Prophets. The Emissary had touched him with Their power. And Yevir’s mission, his future, his every aspiration and ambition, was based upon his own steadfast, unwavering, unquestioning belief in the Prophets and Their plan.

He gathered his thoughts carefully before answering Mika. “You’ve been taught by Solis. And Dukat. And the Prophets only know how many others. So you must know better than most that prophecies may be interpreted in manyways, especially by those eager to bend those prophecies to their own agendas. Gray can be made to resemble black or white, depending on the elements that surround it. So too can heresies seem to offer solace, especially in times of turmoil.”

Her smile bore a trace of sardonic humor. “Why do you immediately say that the gray is black, instead of white? Have you truly opened your heart and mind to the possibilitiesOhalu offers Bajor? Yes, our world is in turmoil. It is going through a rebirth, transitioning from the Occupation to freedom, from war to peace, from an independent world to a member of an interstellar coalition…. Isn’t it possible that the faith of the Bajoran people needs to experience a similar rebirth as well?”

“The Bajoran people need their faith in the invariant will of the Prophets,” Yevir said, allowing some steel into his voice. “Particularly in times such as these.” Not for the first time, he wondered if the Emissary had placed him on the path to becoming kai merely to have him preside over his flock’s disintegration. The thought was a lance that pierced the depths of his soul.

“You may be right,” Mika said. “Placing our faith in all-powerful beings who want to take care of us is tempting indeed. It absolves our people of personal responsibility. Everything we do, or whatever is done tous, is the will of the Prophets. And for those who deny Them, there is nothing but shame and censure.”

“The Truth of the Prophets cannot be denied, child.” Yevir recalled the screams of a mortally wounded resistance fighter, a young woman who’d died in his arms some fifteen years ago. With her last breath she had cursed the Prophets, whom she’d accused of having abandoned her, her family, and Bajor. He closed his eyes, trying to banish the horror of the memory. “The Truth of the Prophets cannot be denied,” he repeated, embracing the words like a lifeline.

But Mika wasn’t going to let him off so easily. “Where were the Prophets during the Occupation?” she said, her tone growing accusatory. “Why have they not aided us in the rebuilding of our world? Why have those who claim to most strongly represent the will of the Prophets been unable to establish a lasting peace with the Cardassians?”

Feeling a frustration he’d not experienced since the Occupation beginning to steep within his soul, Yevir turned his back to her, his hands clenching and unclenching out of her view. He swallowed his distress and mounting rage quickly– Let the Prophets’ love flow through me—and turned back to her. “Is this why you came to see me today? To spout the polemical blasphemies of Ohalu?”

“No,” she said, her eyes clear and placid. “I am not here to convince you to bless the Ohalavaru.”

Yevir recalled having heard that name bandied about in derogatory fashion by some of his fellow vedeks. The translation of the ancient High Bajoran word struck him as ironic. “‘Ohalu’s truthseekers’?”

“Yes. That is the name of our sect.” She paused, holding her hand palm outward in a placating gesture. “As I said, I’m not here to debate theologies, or even to convince you to respect our faith. But I have come to you to ask for your help.”

Yevir sat down in his chair, looking past the jevonite statue at the woman. “With what?”

“I believe– webelieve that Colonel Kira Nerys has been done a great injustice by the Vedek Assembly. In your own address to the Bajoran people, you said that we needed to reevaluate the old ways and seek new answers to old questions. To keep our minds open. Kira is guilty of nothing but allowing the Bajoran people the chance to question their faith. To decide on their own which answers they will accept…whether those answers come from the Prophets or from themselves.”

Yevir was sorely tempted to interrupt her again, but forced himself to sit quietly and allow her to continue. “As you may recall, it was Kira who saved my life, my husband’s life, and the life of my child. And all the others who had followed Gul Dukat to Empok Nor. Afterward she provided us with more knowledge—and helped us all reevaluate our decisions of faith. Nowshe has merely done the same thing for Bajor as a whole.”

“Comparing your decision to abandon the Pahwraiths to the questioning of the Prophets isn’tlikely to win me over,” Yevir said, unable to keep the frost from his tone.

“One learns only by asking questions,” Mika said, almost serene. Yevir recognized the words as one of Solis’s most oft-quoted aphorisms. “One only grows by seeking answers. Some of those who have read the prophecies of Ohalu have rejected them; Ohalu’s answers did not suit them, and their faith in the Prophets became strongeras a result. But others have found that they want to continue their spiritual explorations.” She paused for a moment, appearing to search for the right words. “Even the Emissary questioned openly who and what the Prophets are, and what Their role in Bajor’s past, present, and future really might be.”

Wearying of the debate, Yevir rubbed his forefinger and thumb over his nose ridge, closing his eyes for a moment. Finally, he said, “I will notrescind Kira’s Attainder. Whether or not the questions Ohalu poses are valid is not a factor in the Assembly’s decision. And Kira’s decision to disseminate Ohalu’s heresies without regard to their effect on Bajor’s religious community—especially now—is unforgivable.”

Mika frowned. “You must hate her very much, Vedek Yevir. I am disappointed.”

“No, child,” he said. Ever since Kira’s act of betrayal, Yevir had searched his soul carefully for such unworthy motivations. He had found none. Indeed, he had agonized over the Attainder decision. “Though I can understand how it might appear that way. I know the Attainder must be personally devastating to her.”

“Then surely you can find it in your heart to forgive her.”

“Actions such as hers are beyond my authority to forgive. Kira has taken it upon herself to affect Bajor’s spiritual well-being—without training, without warning, and without official sanction. To be blunt, this makes her simply too dangerous to keep within the faith.”

He expected Mika to react angrily to his plainspoken argument, as the Emissary’s wife had done when he had rebuffed her attempt to discuss lifting Kira’s Attainder. But instead, Mika merely seemed more resolute. “I understand,” she said. “I had to try. Still, there are others in the Assembly who may be less…inflexible about their Attainder votes.” She stood, readying herself and her sleeping child to leave. “Vedek Yevir, I hope that one day the Prophets will lead you to the forgiveness of Kira, and to Ohalu’s truth.”

Before he could react, Mika’s child began to fuss, pushing a small hand out of the robes in which it had been wrapped. The hand was chubby and slightly gray in color, its skin rough and leathery. From where Yevir sat, an absurd juxtaposition of the jevonite figure with the child made the baby’s arm appear to be growing out of the statue’s side.

Yevir stood bolt upright. “May I see your child, Mika?”

Mika’s eyes narrowed in response to his swift action, but she obliged him by stepping closer and sweeping the robes away from the child’s sleep-crinkled face. Yevir could see that the boy seemed larger than before, a toddler who looked to be about a year old, rather than an infant.

Yevir stepped to the side of his desk and reached out to touch the boy’s face. His skin had the same grayish cast as his limbs, as well as another, somewhat unexpected trait. On the slumbering boy’s nose was a fully developed set of Bajoran ridges, while his brow and forehead were framed by the raised scales of a Cardassian. An elevated oval on his forehead held a depression in its center, in the shape of an elegantly crafted spoon. The boy’s eyes, which had just opened, were of a crystalline black and seemed to watch the vedek with an intensity that matched Yevir’s own.

The vedek’s hand traced the ridges on the child’s forehead, and the boy grasped his finger, chattering happily. Yevir found himself smiling in wonder. Looking up, he saw that Mika was smiling as well.

The child is at peace. He has erased the tension we both felt, bridged our two worlds.

Yevir’s mind raced. He stepped back, gesturing toward the door. “Thank you, Mika. Your son is beautiful. I will consider your words. If you will consider mineas well.”

As the young woman turned to leave, she said, “I consider the words of many, Vedek Yevir. Wisdom and freedom can be fully gained only by opening one’s mind.”

She was quoting her uncle again. He smiled. “Walk with the Prophets.”

“And you,” she said. And then she was gone.

Yevir sat down behind his desk and immediately reached for the gold-hued jevonite statue. The figurine had come from the ongoing excavations at B’hala, brought to the Emissary’s wife by one of the prylars working at the site. Yevir wasn’t sure why he felt so strongly connected to the artifact. The figure was peculiar, bearing little resemblance to the more primitive art found elsewhere at the dig. It was a humanoid shape swathed in robes. Its eyes, though mere carvings, still managed to appear as though they watched anything in view. Its nose was ridged like a Bajoran’s, but its forehead also bore raised, scaly scar patterns. Its neck was long and gracefully sloping, held up in pride and unbowed by adversity. When Yevir had first laid eyes on the figure, he had wondered if it represented some millennia-dead Bajoran martyr or holy man, whose facial disfigurements bore testament to the trials he had endured in the name of the Prophets. But almost immediately he saw that it held a deeper, subtler meaning.

Using the same hand with which he had touched Mika’s child, Yevir now caressed the face of the small statue, and he became utterly certain, at last, what the object represented—the melding of a Bajoran and a Cardassian. The blending of the Bajoran nose ridge with the forehead scales of a Cardassian was unmistakable. And why hadn’t he noticed the subtle ridges running down both sides of the figure’s neck before? The statue was obviously the image of a mixed-heritage child like Mika’s, though it was carved millennia before the two planets could possibly have produced such a union. Before, in fact, either people had met or even known of one another’s existence.

Like the hybrid child he had just touched—and like Tora Ziyal, whose memory the Cardassians had resurrected in their overtures of peace—the statue represented a commingling of related species.

It is a symbol of unity.

Hope surged within Yevir’s breast, and his earlier feelings of despair vanished like mist over the fire caves. Replacing them were a cacophony of thoughts and plans, an epiphany of what he must now do.