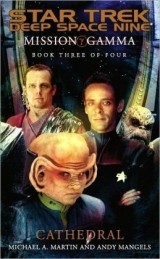

Текст книги "Cathedral "

Автор книги: Andy Mangels

Соавторы: Michael Martin

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

Vaughn sat in the command chair, listening to the various busy sounds of the bridge consoles. He quietly mulled over what Ezri had just told him before she returned to the medical bay to assist Candlewood and Richter with their quantum-scan analyses. Clearly, the Oort cloud artifact—which, according to Shar, the aliens regarded as either a place of worship or as a chamber of horrors—held the solution to the puzzle of what had befallen the shuttlecraft Saganand her crew.

And he was determined to get his hands on that solution, no matter the cost.

Vaughn rose and approached the science station, where Shar was intent on a scrolling display of the alien text. Many more of the symbols were now separated into groups by variously sized ovals, rather than running in an uninterrupted sequence. It certainly looked promising.

“Making any progress?” Vaughn said.

Shar lifted his eyes from the display only for a moment. “It’s difficult to know for certain. I’m beginning to wonder if Ensign Cassini might have been a bit too optimistic about our chances of success.”

“At least we’re finally able to converse with our new friends,” Vaughn said. He gestured toward the main viewer, where an image of the D’Naali ship hung suspended against the stygian darkness.

D’Naali.Vaughn turned the name over in his mind as his eyes swept the long, tapering lines of their vessel. Relief warred with frustration within him. On the one hand, it was a relief not to have to refer to the insectoid creatures solely as “the aliens” anymore. On the other, Shar’s initial translations of Sacagawea’s speech had yet to shed any real light on the nature of the mysterious space artifact—or on the reason the D’Naali vessel had been chased and attacked.

The turbolift door slid open, and Vaughn turned toward the sound. Lieutenant Nog stepped onto the bridge, leaning heavily on a cane. His new left leg had grown considerably over the past day. At first glance, it was a perfect match for the right one and seemed to be getting stronger by the hour.

Vaughn still found it difficult not to glance at the new limb. “How did the last round of repairs go, Lieutenant?”

Nog smiled, obviously happy to be back in his element. “She’s spaceworthy, just as long as no one else attacks her anytime soon. I told the D’Naali captain he can get under way whenever he needs to. Once we get Sacagawea back aboard his vessel, that is. I have to say, Shar’s revamped translators really made the technical conversations go a lot more smoothly.”

“Does that mean you were able to learn anything more about why the D’Naali were being chased out here?” Vaughn asked. “Our running into them so close to the alien artifact can’t be a coincidence.”

Nog shook his head. “They never did give us access to much of their ship, outside of the engine room and a few of the most heavily damaged portions of the hull. And whenever you ask them a direct question…” He trailed off.

“They’re evasive?” Vaughn prompted.

“I’m not sure it’s deliberate. The translators still haven’t ironed out a lot of the wrinkles in their language. So the D’Naali are about as easy to understand as some of Morn’s Lurian Postmodernist poetry.”

Vaughn had heard some of Morn’s poems shortly after his initial arrival aboard Deep Space 9. The occasion had been an “open mike” night at Quark’s; Vaughn recalled that he hadn’t comprehended so much as a couplet of Morn’s work. He made a mental note to recommend Shar for a promotion if he could coax just a little more performance out of the universal translator.

“Captain,” Nog said, “if you don’t need me up here at the moment, I’d like to get back to engineering. While Permenter and Senkowski and I have been off the ship, Merimark and Leishman have been a bit overworked.” Vaughn watched as Nog looked down at his regrown limb yet again. Nog’s smile made him appear more genuinely happy than Vaughn had ever seen him.

Tenmei was grinning in Nog’s direction. “It’s always best to stay on Merimark’s good side,” she said. “Especially if Leishman’s hid the candy stash again.”

It suddenly occurred to Vaughn that Nog could have saved time by making his report over the intercom. Of course, it wasn’t every day that one’s amputated leg grew back. Who could fault the lad for wanting to use it as much as possible?

“Dismissed,” Vaughn said with a paternal smile, then watched as Nog exited.

He looked toward Bowers, who occupied the tactical console. “Please open a channel to the D’Naali ship, Mr. Bowers.”

“Aye, Captain,” Bowers said.

Moments later, a bug-visaged alien face appeared on the screen, its vertical mouth parts spread in what might have been a D’Naali smile. “Grateful thanks of ours you have, humandefiantcaptain. Indebtedness, with thanks/ beholden again reiterated/multiplied.”

“Not at all. We were happy to assist you.”

“Anything in recompense/requital, we offer with gladness/joy to provide/make available. State the need/ request.”

Vaughn blinked while he parsed the translator’s fractured grammar. Then he realized that the D’Naali commander was not only presenting his thanks, he was offering to provide something of value in return for the Defiantcrew’s labors.

He decided to seize the opportunity. “There is one thing we’d like to ask of you.”

“Denominate that one thing, I request.”

“We need to survey a remote part of this solar system. In the outer comet cloud. We could use a guide who is familiar with the territory.”

The D’Naali lapsed into what seemed a thoughtful silence before he spoke again. “Answer/result is affirmative/positive. Ryek’ekbalabiozan’voslu now dwells aboard your vessel.”

Vaughn realized that the other captain was referring to the D’Naali whom Bowers had dubbed Sacagawea.

“We would be grateful if Sacagawea would act as our guide,” he said, glancing back toward Bowers, who now looked somewhat embarrassed. Vaughn was aware, of course, that the translators had been calibrated to render the nickname into the D’Naali language. “If he is willing.”

The D’Naali captain made a sweeping gesture with one of its slender limbs. “Unneeded it is to check. Ryek’ekbalabiozan’voslu will be/is obligated to be your guide. What time-interval is requested/required?”

“A few solar days at the most,” Vaughn said. “Then we will return your crew member to you.”

The D’Naali captain’s head bobbed up and down. “Assent granted readily/with enthusiasm. After/following five turnings-of-the-star, we will await/expect your return to this place/coordinates.”And with that, he vanished, replaced by an exterior view of the D’Naali ship.

Vaughn returned to the captain’s chair, sat, and looked at the conn station, where Tenmei was posted. Her dark eyes regarded him expectantly, and he could see that she had already laid in a course.

“Best speed to the alien artifact,” Vaughn said.

The flight into the fringes of the system’s Oort cloud, guided by the subspace beacon Nog had deployed during the Sagan’s close encounter, took less than ten minutes. Vaughn ordered Tenmei to bring the Defiantto a relative stop a mere one hundred kilometers from the coordinates where the Saganhad nearly been swept forever out of normal space by the enigmatic artifact’s interdimensional effects.

In the center of the screen, an indistinct structure appeared, growing steadily in apparent size as Tenmei increased the viewer’s magnification levels. At first, Vaughn thought it might be one of the countless dead, icy bodies that spangled this cold, remote region of the system. These objects were diffused throughout the Oort cloud, covering a volume of space so vast and dimly illuminated by this system’s distant sun that any one icy body was scarcely distinguishable from any other.

But the object that was growing on the screen swiftly resolved itself into something else entirely. Its artificial nature was now clearly discernible, as it continued its stately, eternal tumble through the unfathomable interdimensional deeps. Its shape was constantly morphing as new, hitherto unseen facets rolled into view. Spires, arches, buttresses that evoked Gothic buildings appeared and vanished, each in their turn. Curving, swirling lines seemed to fall into existence, then straightened into right angles, contorting immediately afterward into shapes that no mind could fathom but which nevertheless bewitched the eyes.

The feeling of awe that had descended upon him when he’d first viewed a holographic image of the object returned tenfold. In spite of himself, Vaughn had to wonder if he was staring into the business end of another one of the universe’s transcendent, inquiry-resistant mysteries. He recalled the peaceful, floating death-dream he’d experienced after touching a Linellian fluid effigy, a memory that remained green despite being nearly eight decades old. The artifact also brought to mind the life-changing epiphany he’d received from the Orb of Memory, when he had helped recover it from the derelict Cardassian freighter Kamalonly a few months earlier. That encounter had forever altered the trajectory of his life, ultimately leading him to DS9, the Defiant…and finally out here, to confront the ragged edge of the human experience. In the presence of the weird alien construct, he could not help but recall his far more recent sojourn on the world of the Thoughtscape entity, which had forced him to confront the many mistakes he had made as Tenmei’s absentee father. Over his almost eighty years of Starfleet service, he had witnessed enough inexplicable events to credit the notion that some things just might remain forever beyond human ken.

During the Defiant’s approach, the bridge’s population had gradually increased. Vaughn glanced around the room and noted that Shar, Merimark, Gordimer, and science specialists T’rb and Kurt Hunter were all present. Along with Bowers, they stood totally still, staring owlishly at the geometrical contradiction that slowly somersaulted end over end on the screen, a conglomeration of Platonic shapes viewed through a tumbling kaleidoscope.

Vaughn’s feelings of awe were being steadily mellowed by an overtone of caution. He couldn’t help but recall Bowers’ report on Sacagawea’s obviously conflicted feelings toward the ancient edifice that now held the entire bridge so spellbound.

Cathedral. Or anathema.

A hard determination rose within him to get at the truth of it, no matter what it took. Cathedral. Anathema. Either way, the artifact represented the only hope of reversing—or even understanding—whatever changes it had wrought upon his first officer, chief medical officer, and chief engineer.

His friends.

Vaughn saw that Tenmei was already running a series of passive high-resolution scans on the object’s interior.

“Anything, Ensign?” he said.

“Negative, Captain. It’s a blank wall.”

“We’re going to have to work for it, then. Switch to active mode.” He turned to Shar and T’rb, who had already begun busying themselves at a pair of adjacent consoles on the bridge’s upper level. “The moment our sensors turn up the smallest sign of internal activity, I want to know about it.”

“Standard sensors negative,” T’rb said. “It’s like the thing isn’t there.”

Vaughn smiled. T’rb’s off-the-cuff comment was almost literally true, since most of the artifact’s mass lay outside normal space.

“I’m picking up a graviton absorption signature,” Shar said. He sounded almost triumphant, as though he’d just proved a pet theory. “Evidently the object is sweeping up energetic particles and carrying them into its own higher-dimensional spaces.”

“What about positron tomography?” T’rb said to Shar.

“Already engaged.” Shar frowned, his antennae and his gray eyes seeming to work in concert in an effort to bore a hole in his instrument display. “There,” he said at length. “I’m reading a hollow space in the object’s interior.”

T’rb and Tenmei immediately tied their consoles in with Shar’s. They quickly began nodding to each other, confirming Shar’s discovery.

Then T’rb scowled at his readings. “The boundaries of the hollow space seem to be fluid. In motion.”

“I see it, too,” Shar said. “It must be a distortion effect caused by the object’s being in multiple dimensions simultaneously.”

“Or our sensors are just reading it wrong,” T’rb said dryly.

Vaughn didn’t like the sound of that. “Ensign Tenmei, can we beam an away team safely into the interior?”

Tenmei looked at her console again as though to double-check, then nodded. “I believe so, though I can’t get a reading on the atmospheric composition, if any. And Chief Chao had better stay away from those shifting boundaries.”

“I’ll tell her to aim for the middle.” Vaughn said, and turned back toward Shar. “Lieutenant ch’Thane, I want you to assemble an away team, with full environmental suits. Jury-rig an EV suit for Sacagawea and bring him along.”

“Yes, sir,” Shar said. “I request permission to lead the team as well.”

“I don’t think so, Lieutenant,” Vaughn said with a gentle shake of the head. “I want to keep you on board. We still need a working translation of that alien text, and so far you’re better grounded in it than anyone else.”

The young Andorian’s eyes flashed with an intensity Vaughn had never seen before. His aspect was half plea, half fulmination. “The computer and some ancillary equipment are handling the bulk of the work now, sir.”

It wasn’t like Shar to argue with him right on the bridge. Something was wrong. For some reason, the usually reticent science officer appeared to needto go.

“All right, Shar. You can come along. But I intend to lead the team myself. I want to keep a low profile, but I also want plenty of secur—”

“Incoming bogeys, Captain,” Bowers said, his fingers suddenly moving at blinding speed across the tactical console.

Vaughn shifted instantly into his combat-imminent mode as everyone who had been standing about watching the screen scattered to various battle stations. “Are they coming from the artifact?”

“No, sir,” Shar said from the science station, fully intent once again on his own console. “From the sunward direction.”

“How many?” Vaughn wanted to know.

“Eleven,” Bowers said. “No, thirteen ships. Closing fast, in a tight wedge formation. Configuration matches the hostiles we chased away from the D’Naali ship. And they’re powering weapons.”

Though his heart thudded heavily in his chest, Vaughn maintained a studied outward calm born of decades of practice. “Yellow Alert. We’ll maintain a passive posture as long as possible, but I want you to keep the shields and phaser banks warm, Mr. Bowers. And give me a tactical display.”

The image of the mysterious alien edifice vanished, replaced instantly by a baker’s dozen bulbous, blocky aggressor vessels, each of them very similar to the ship that had opened fire on the Defiantand the D’Naali earlier.

“Lead ship’s range is three hundred thousand kilometers,” Bowers said. “Closing fast.”

“Hail them, Mr. Bowers.”

The ships continued their inexorable approach. “One hundred and fifty thousand,” Bowers reported.

Vaughn rose. “Any response?”

“Negative.”

“Keep trying,” Vaughn said. “And ready phasers.”

Bowers: “Sixty thousand and closing.”

“Aren’t you going to raise shields, Captain?” Tenmei said. Vaughn heard the subtle Are you nuts?timbre that colored the phrase.

“Not yet. Be ready to fire on my command, Mr. Bowers. A shot across the lead ship’s bow.”

“Aye, Captain,” Bowers said, showing no sign of apprehension.

Then, to Vaughn’s immense surprise, the aggressor flotilla broke formation, with most of the ships tumbling rapidly away from the Defiant.

“They must have picked up our weapons signature,” Tenmei said. “Maybe we scared them off.”

“I wouldn’t count on that, Ensign,” Vaughn said.

Bowers consulted his console and quickly confirmed Vaughn’s suspicions. “They’ve slipped around and behind the artifact. Now they’re coming around toward our side of it and are taking up new positions between us and the object.”

“Confirmed,” Shar said.

Vaughn fumed silently. Damn! Suckered me. They weren’t planning to attack. They were trying to set up a blockade.

Aloud, Vaughn said, “Hail them again, Shar.”

Shar’s antennae lofted in surprise. “Sir, theyare hailing us.”

“Put them on.” And let’s hope the translator that’s good for the goose is also good for the gander.

The viewer image shifted again, this time revealing a dimly lit ship interior. A squat being that reminded Vaughn of nothing so much as a blotchy snowman draped in seaweed regarded him with an inhuman, unknowable expression.

This could only be a member of the species that Shar’s enhanced translator had tentatively identified as Nyazen.

The translator spoke in a voice that evoked something halfway between wind chimes and highland pipes: “Cathedral/anathema never you to be sullied/defiled by seekers-of-curiosity, such as we believe/intuit to be your motive/purpose/goal.”

He doesn’t want us near the artifact. Either because it’s holy, or because it’s dangerous.

Vaughn spread his hands in what he hoped the Nyazen would take as a benign gesture, though he wasn’t at all certain that the creature even hadhands as such. “I understand that you don’t wish to let strangers approach this…object. But it has brought harm to members of my crew. We believe that it also holds the key to undoing that harm.”

“Believe you, we cannot. Your vessel, a D’Naali contains/shelters. Blood-foe/ancient-vow-to-destroy D’Naali represent/are/shall ever be. Trust with you not achievable/ advisable, therefore.”The Nyazen abruptly vanished from the screen, replaced by the artifact, slowly tumbling through the yawning interdimensional gulfs.

It took Vaughn only a moment to gather the Nyazen’s meaning. His sensors have picked up Sacagawea’s presence aboard theDefiant.

Bowers spoke quickly, his voice half an octave higher than usual. “Energy readings spiking aboard all thirteen ships’ weapons tubes.”

“They’re opening fire,” Tenmei said.

It was no longer possible to read any ambiguity into the Nyazen fleet’s motives. “Shields up, Mr. Bowers!” Vaughn said. “Lock and load.”

11

“Well, you’re certainly not one of my regular customers,” Vic said, appearing mildly surprised. “What brings you to my establishment this fine afternoon?”

Taran’atar regarded the holographic human simulacrum stonily for a long moment before replying. Because his senses were attuned to energy fluctuations—such as those made by shrouded Jem’Hadar—he remained keenly aware of the twenty or so luminal demihumans who milled about the restaurant and dance floor of Vic Fontaine’s lounge. Only one of these beings, a gray-haired humanoid who sat drinking alone at a small corner table, appeared to have any discernible substance. Taran’atar decided that he would do well to keep an eye on that one.

“I walked,” Taran’atar said, turning his attention back to Vic. The tuxedoed human bared his teeth in what all humans and Vorta seemed to regard as a nonthreatening gesture. Taran’atar had never enjoyed looking at teeth, whether human or Vorta.

“And I thought Frank and Dean were the greatest straight men who ever played Vegas. They’re not gonna be happy to hear about the competition, pallie.”

Taran’atar wasn’t at all certain what to make of the holo-human’s remarks. “Are you saying I’m not welcome in this establishment?”

“I’ll confess to preferring to see you in a tux,” Vic said, indicating his own smart black-and-white ensemble before looking the Jem’Hadar’s dark, featureless coverall up and down. “Or even a sportcoat. On the other hand, at least the getup you’re wearing is black.”

It had been many weeks since Taran’atar had given any thought to his apparel. “Colonel Kira ordered me to wear something other than my Dominion uniform. And it’s the will of the Founder you call Odo that I obey the colonel’s every order.”

Vic’s smile slanted very slightly to the side. “I had a feeling when you walked in here that you’d be the life of the party. So what can I do for you?”

Taran’atar suddenly realized that he wasn’t certain exactly how to verbalize what was on his mind. At length, he said, “Many of the station’s residents have come to value your advice.”

Vic made a self-deprecating gesture with his shoulders. “I only tell them what I see. But it isn’t always what they want to hear.”

Taran’atar nodded. “Perhaps that’s why so many of the humanoids have exhibited so much…faith in you.”

“Whoa there. Faith is a concept I leave to the earring crowd, capisce?I’m only an entertainer.”

“I’ve been told that your intervention prevented Nog’s death.”

Vic’s eyebrows shot up and he seemed to be at an uncharacteristic loss for words, at least for the moment. After a pause he said, “Nog was pretty deep down in the dumps last year after losing his leg. He spent a lot of time here while he was recovering.”

Taran’atar had not forgotten that it was Jem’Hadar who had been responsible for Nog’s injuries. And shortly before his departure for the Gamma Quadrant, Nog had made it abundantly clear that hehad not forgotten that fact either.

“I take that to mean that he was emotionally distressed after losing his limb in battle,” Taran’atar said.

Vic nodded. “And how.”

“Quark told me that you personally prevented Nog from dying.”

“I only helped nudge him back into the real world. But Nog had to decide to do the living for himself. He learned to believe that things might get better for him out in the big bad universe if he’d just get out there and start participating in it again.”

“So…Quark was merely being hyperbolic when he praised your abilities.”

“I try not to think too much about what my reviewers say, pallie. Other people will believe whatever they want to believe, about me or anybody else. And that’s probably the way things oughta be.”

Taran’atar was growing increasingly bewildered. “You don’t lay claim to any special psychotherapeutic talents. Yet others believe you possess those talents.”

“Everybody has to have faith in something. For instance, you have faith that the Founders are gods, don’t you?”

Taran’atar mulled that over momentarily. “No, I do not. Believing that the Founders are gods requires no faith on the part of a Jem’Hadar.”

“Why’s that?”

“Because the Founders aregods.”

Vic shrugged again. “You ask a silly question—”

At that moment, Taran’atar became aware of some motion from the far corner table. The iron-haired humanoid he had noticed before had risen to his feet and was now walking in his direction. Taran’atar instantly noticed three things about the man: he was far taller and broader than he had appeared while seated; he was wearing an equally outsize black-and-white suit; and he was very definitely not a hologram.

“Have you two met?” Vic asked as the large man came to a halt within arm’s reach. “I think you may have a fair amount in common.”

Taran’atar faced the humanoid, and finally recognized him.

“This was the last place in the quadrant I expected to encounter a Jem’Hadar,” the humanoid said, his expression neutral. But Taran’atar was relieved to note that the man made no effort to shake his hand, a human gesture that he still had not gotten used to.

“I didn’t know that Capellans were interested in human popular culture,” Taran’atar said. “You are Leonard James Akaar, fleet admiral, Starfleet. I did not recognize you right away because of your tuck-seedoh.”

Akaar chuckled and raised a glass to his lips before responding. “I discovered long ago that human history and culture have much to recommend them. As they say on Earth, ‘When in Rome, do as the Romans do.’ Nowtell me—what compels one of the soldiers of the Dominion to sample the historic pleasures of one of the Federation’s founding worlds?”

“I’m not here in my capacity as a soldier. My current mission is one of peace. I’ve been instructed to learn all I can about the peoples of the Alpha Quadrant.”

“Yes, I have been briefed about the mission on which Odo has sent you,” Akaar said knowingly, then raised his glass toward Vic, who was listening attentively to the exchange. “You will find Vic to be quite a perspicacious host, Mr. Taran’atar. We do indeed have much in common, you and I. Though I confess to finding it somewhat strange that we both appear to be so at ease in one another’s presence.”

“I don’t understand,” Taran’atar said.

Akaar frowned. “You cannot be serious. Tell me—how many Jem’Hadar do you think I killed during the war?”

“I couldn’t say,” Taran’atar said, though there was no heat beneath his words. During war such things were to be expected. But now that the war was over, it was of no consequence.

“Tens of thousands,” Akaar said. “Perhaps a hundred thousand or more. Sometimes I did it from the bridge of a starship, or from a starbase wardroom, or from Starfleet Headquarters. And I dispatched many of them at close quarters, sometimes with a hand phaser, and on other occasions with my triple-bladed kligat.”Akaar fell silent, though he looked expectantly toward Taran’atar.

Vic winced as the tension appeared to escalate. “Fellas, please tell me you’re not planning on trashing my place. The guys in the band are still jumpy from all those times Worf went berserk in here last year. And I’m not paying the bouncers enough to even thinkabout going toe-to-toe with either one of you.”

Then Akaar laughed, a low throaty sound. He placed his right fist on the left side of his chest, then extended his palm outward toward Vic. “Be at peace, Vic. Like Mr. Taran’atar, I have come to this place with an open heart, and open hands.”

“Your experiences during the Dominion War interest me,” Taran’atar said. “But why tell me of the Jem’Hadar you’ve slain?”

“Because my aged ears overheard your discussion of faith, and it piqued my interest. Do you know why I have come here, Mr. Taran’atar?”

“To this lounge?”

“To this space station.”

“You are one of the Federation dignitaries who will bear official witness to Bajor’s entry into the Federation.”

Akaar nodded. “An action that, in itself, is an act of faith. When a world joins the Federation, it is a most serious occasion. A time of both celebration and contemplation. Of faith.”

Taran’atar recalled how carefully the Dominion’s Vorta managers had worked to optimize the usage of each newly annexed planet’s resources for the benefit of the Founders. But such things were merely prosaic facts of existence. They had been done with little ceremony or fanfare, other than the ordinary rituals and recitations that custom dictated surround the daily dispensations of ketracel-white.

“Again, I do not understand,” Taran’atar said.

Akaar sighed, as though he had just failed to convey the intuitively obvious to a dull-witted child. Taran’atar felt his frustration rising at his failure to comprehend things that these Alpha Quadrant natives appeared to grasp so instinctively.

“I have faith,” Akaar continued, “that the years of transformation which began after the Cardassian Occupation ended have prepared Bajor to integrate itself into our coalition of worlds. I have faith that an indissoluble bond will result between Bajor and Earth, Vulcan, Andor, and the scores of other Federation planets.”

Something occurred to Taran’atar then. “I noticed that you did not number your own world among those others.”

Akaar lifted a single ropy eyebrow. “Quite right. Capella has petitioned for Federation member status many times. But my countrymen are not yet ready, even after more than a century of civil war. They still have much to learn about the ways of peace.”

“Interesting. Until seven years ago, Bajor was in a permanent state of military occupation and guerrilla war. And yet the Federation has agreed to admit Bajor before Capella. Does this not anger you?”

Akaar’s eyes narrowed, and for a moment Taran’atar wondered if he would have to defend himself. But the admiral never moved. “If Bajor becomes a productive Federation member, it will bode well for other candidate worlds that have known the scourge of war during living memory. I have faith that Bajor’s success will one day lead to the same for Capella. Perhaps not while I live. But someday.”

Faith again. Taran’atar was beginning to find the concept most vexing. “But is not faith required only when no other factual basis exists for believing in a thing?”

Akaar downed the remainder of the contents of his glass, then fixed a steely eye on Taran’atar. “Precisely. Because we cannot know in advance what will happen, no matter how much we prepare. Consider Bajor again. There are some who believe that the Bajorans should not enter the Federation until after they make peace with their old enemies, the Cardassians, on their own. But there are many more who believe that Bajor is ready for membership now, and that peace with Cardassia will flow inevitably from her Federation allegiance. Both sides, however, are acting on faith.”

Taran’atar found that his own curiosity had been piqued. “On which side have you placed yourfaith, Admiral?”

An enigmatic smile slowly spread across Akaar’s face. “It is not my nature to advocate waiting over action. I believe Bajor to be more than ready for Federation membership, just as she is today. But no Capellan who hopes to live as long as I have believes that peace can everbe inevitable.”

This last was the first straightforwardly sensible thing Taran’atar had heard the admiral say so far. And he also intuited that it gave him an opening to ask another question that had begun nagging at him.

“Why did you not ask me how many humans Islew during the war?” Taran’atar said quietly.

Akaar’s expression suddenly grew dark, and Vic once again appeared worried. “Maybe we ought to steer clear of politics for the rest of the afternoon,” the holographic host said.

Taran’atar wondered with some dismay whether he had once again trodden across one of the Alpha Quadrant’s many indefinable social taboos. These humanoids seemed to hide them everywhere, like subspace antipersonnel mines.

He decided he could lose little by pressing on. “Perhaps it will ease your mind to know that I never entered the Alpha Quadrant during the war. I never fought against the Federation or its allies.”

Akaar’s glower was slowly replaced by a more thoughtful expression. He nodded. “Perhaps it will at that.” Then, setting his empty glass on a passing waiter’s tray, the fleet admiral made ready to leave.