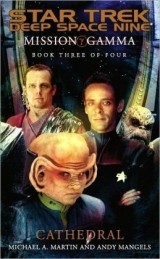

Текст книги "Cathedral "

Автор книги: Andy Mangels

Соавторы: Michael Martin

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

“A police station,” Bowers said.

“An interdimensional ski lodge,” Tenmei said with a tiny smirk.

“A hospital,” Dax said quietly. “Or a church.”

“Whatever it is,” Bowers said, “could it be related to the fight between our alien guests and the folks who attacked them?”

“Until we crack the language barrier,” T’rb said, “the reasons for that conflict will pretty much be anybody’s guess.”

Bowers scowled. “Maybe not. It would help if some of our engineering detachment could snoop around a bit aboard the damaged ship. See if they can find what they’re doing way out on the fringes of this system.”

“Unfortunately,” Vaughn said, “the aliens seem to be supervising every move our people make over there. It looks like interviewing our patients may be our only hope for figuring out the aliens—and the artifact.”

Vaughn noticed the wry smile that had appeared on the doctor’s face at Ezri’s suggestion that the artifact might be a church of some sort. “Regarding the alien object,” Bashir continued, looking in Ezri’s direction as he spoke, “all we really know is that an intelligent and perhaps extinct species built it more than five hundred million years ago for some purpose which remains obscure. We also know that this structure possesses certain higher-dimensional characteristics that we don’t fully understand. We really don’t have any other information—except for the alien text file we downloaded from one of the thing’s internal computers.”

Vaughn smiled back at Bashir. From Vaughn’s perspective, the doctor was a mere pup. Vaughn knew that in his century-long life, he’d very likely forgotten more than even a genetically enhanced thirty-five-year-old could have learned. But Vaughn was often impressed by how painstakingly empirical Bashir could be in the pursuit of knowledge. And he was occasionally amused by the young doctor’s apparent obliviousness to all matters mystical. He recalled the Orb experience that had led to his taking command of this ship—and to this mission. Yes, mortal beings had built the alien artifact; this was not the work of enigmatic gods or supernatural spirits.

But knowing those facts made the thing no less wonderful or awe-inspiring to Vaughn.

Aloud, he said, “That alien text file has got to be the key to discovering the artifact’s origin and purpose.” He fixed his gaze on the Defiant’s security chief. “Mr. Bowers? Lieutenant Nog placed the text file in your care. Please give us a report.”

Bowers touched a control on his padd, and the holographic image of the alien artifact was replaced by scrolling lines of swooping, unreadable characters. “For starters,” Bowers said, “the file is huge.More than eighty megaquads, which is about a third of our computer core’s overall storage capacity.”

“That fact alone is going to put a real strain on our number-crunching—or, in this case, text-crunching—resources,” said Cassini.

“It’s too bad we have to tie up so much of the computer core,” Tenmei said, “with a document we can’t even read.”

“You mean we can’t read it yet,”T’rb said, apparently very sure of his abilities. “Cassini and I have already started running a cross-comparison between this text and samples of written language groups we’ve downloaded from adjacent sectors of Gamma Quadrant space.”

Cassini sounded equally confident. “It might take a while, but if we’ve ever flown anywhere near the Gamma Quadrant’s equivalent of the Rosetta stone, we’ll crack this thing. It’s just a matter of time.”

“Perhaps then we’ll also be able to converse with Dr. Bashir’s new patients,” Vaughn said.

Bowers leaned back wearily in his chair. “That would be a relief, sir. It’s damned difficult to work out repair schedules and visits to the aliens in the medical bay when all you have is the one or two concepts the universal translator can recognize. Everything else comes down to hand gestures and interpretive dance.”

“We can’t assume that the language the Kuka—that the aliens speak,” Bashir said, “is in any way related to the ancient text.”

It’s not like Julian to stammer like that,Vaughn thought, scowling. Glancing at Ezri, he thought he noticed something different about her as well. She seemed to be getting rather pale. And was one of her eyelids beginning to droop?

Stroking his neatly trimmed beard, Vaughn said to Bashir, “I want to know more about this interdimensional wake the Saganencountered near the artifact. Specifically: Could it have had any harmful effect on the shuttle’s crew?”

Bashir paused for a moment before answering. “It’s possible, sir. But I’ll need to run some tests before I can say for certain.”

“I haverun some tests,” said Tenmei. Vaughn and Bashir both favored her with a blank look. “On the Saganitself, I mean. The Saganis in close to optimal condition. Except for a peculiar quantum resonance pattern, that is.”

“Meaning what?” Vaughn said.

Tenmei shook her head and shrugged. “I wish I knew.”

Vaughn abruptly put aside every reverent thought he’d had about the alien artifact thus far. He didn’t like the direction this was taking one bit.

Vaughn looked at Ezri again. This time he had no doubt—she was indeed looking pale. Why hadn’t Julian noticed? “Lieutenant, how long have you been feeling ill?”

Ezri sighed wearily, evidently deciding it was best to come clean. “It happened…I think it started during the flight back from the alien artifact.”

“I see.” Vaughn was fully aware that this fact might or might not be significant. Shifting his gaze to Bashir, he said, “Has anyone else from the Sagan’s crew experienced any symptoms?”

The doctor suddenly looked uncomfortable, as though he wanted to be parsecs from the mess hall. He appeared to be groping for words.

That wasn’t like him at all.

“Doctor?”

“I…believe I may have experienced a lapse in concentration while tending to our alien patients,” he said finally. “I’m not at all certain what to make of it. If anything.”

Vaughn felt his cheeks flush with anger. He glared first at Bashir, then at Ezri. “And you were both planning on reporting these difficulties exactly when?”

Bashir stiffened at that. “With respect, sir, at the time neither of us was aware that there wasa problem. I’m still not entirely convinced there is one now.”

Vaughn moved his hand through the air as though to wave the question of timeliness away. “All right. But what about Nog? How has he been feeling?”

“I’ll contact him,” Bashir said. “He’s still making repairs to the alien vessel.”

At that moment, Dax cried out and collapsed across the conference table, clutching her belly and screaming in pain.

Ignoring the pain raging in his leg, Nog watched as the alien EPS conduits finally lit up in the correct sequence. Power had begun flowing into the proper channels. And, more importantly, nothing had exploded.

Permenter heaved a theatrical sigh of relief, then displayed an I-told-you-it-was-going-to-workgrin to the still sheepish-looking Senkowski. Even Shar wore a triumphant smile, which Nog knew was a carefully constructed affectation on the Andorian’s part, for the benefit of the humans around him. Even the alien engineer looked pleased, his chitinous mandibles moving from side to side to display what might have been happiness or gratitude.

“Release the magnetic bottles now, Shar,” Nog said. After Shar touched the appropriate controls, Nog could feel the rumble in the deckplates that signaled the resumption of a controlled matter-antimatter reaction. Now that warp power was partially restored, the rest of the repairs would go forward much more easily. Force fields could be erected strategically throughout the ship, buttressing the collapsed sections and reinforcing the crude patching that had already been applied to some of the exterior hull breaches.

But I won’t have to supervise the rest of it directly,Nog thought, now eager to get to the Defiant’s medical bay so that Dr. Bashir could examine his leg.

The deckplates continued throbbing, with increasing intensity.

The throbbing sensation moved up from the deckplates and into Nog’s left leg, which suddenly felt as though it had been thrust directly into an unshielded antimatter pile. Nog screamed and watched the bulkheads trade places in slow motion. Deck became wall. Bulkhead became ceiling. His back pressed up—or down?—against something cold and unyielding.

He looked up, straight into the impenetrable eyes of the alien engineer. Beside the alien stood Shar, his image pulled and twisted as by a crazily warped mirror.

“Defiant,emergency beam-out!” he heard Shar shout as darkness engulfed him.

7

Two weeks,RO thought as she leaned back in the chair behind the security office desk. Unbidden, a muscle in her upper back began rhythmically clenching and unclenching itself. Rolling her shoulders to work out the kink, she tossed the padd containing the incident report—the unfinishedincident report—onto the desk.

Two weeks, and I’m still mopping up after Thriss.

The door chime rang. Ro looked through the glass to see who was trying to monopolize her time now.But the moment she saw who it was, she relaxed and ordered the computer to open the door.

“Didn’t expect to find you still in your office so late, Ro,” said Lieutenant Commander Phillipa Matthias, leaning tentatively through the doorway. “Got a minute?”

Ro smiled. She genuinely liked the station’s new counselor, not simply because she was friendly toward her—not to mention solicitous of her sometimes prickly moods—but also because she spoke plainly and directly. Starfleet counselors were rarely so refreshingly free of professional psychobabble as was Matthias.

Ro also knew that she could rely on Phillipa not to waste her time. “A minute?” she said as she rose from behind her desk and stretched. “I’ve got as many as you need. Tell me: Have the Andorians agreed to talk to you?”

Phillipa bit her lip, looking uncharacteristically uncomfortable. “Well, doctor-patient confidentiality would have constrained what I could tell you. IfDizhei and Anichent had decided to open up to me. But they haven’t. Frankly, I’m not a bit surprised. Andorians aren’t known for being overly fond of the counseling trade.”

“I wonder why.”

“It’s the antennae.”

“Come again?”

“Those antennae are a wonderful means of nonverbal communication. Sometimes unintentionally so. That’s why Andorians are lousy at keeping their poker hands a secret, but absolutely terrific at judging other people’s emotional states. They probably realize it, too, which explains why they aren’t keen on having counselors around. Especially when they’re this raw emotionally.”

Ro felt another slow, pounding, warp-core-breach of a headache coming on. She understood, and sympathized with, the anguish Anichent and Dizhei were experiencing. She recalled all too well the desolation she had felt after a Jem’Hadar minefield claimed the life of Jalik, a fellow Maquis fighter. And there had been her father’s grisly death at the hands of Cardassian torturers, which she had witnessed at the tender age of seven. But she also knew that it was possible to survive such horrors. Despite all the death and cruelty she had witnessed during her brief span, Ro had never felt so completely paralyzed as those two young Andorians seemed to be. After so many interminable days of mourning, couldn’t one of them find the emotional wherewithal to give her a somewhat coherent statement regarding Thriss’s death? Even in the face of personal tragedy, official reports still had to be filed.

Life had to go on for the surviving members of Shar’s bondgroup.

“Have they let Dr. Tarses speak with them?” Ro said. “Or changed their minds about letting him perform an autopsy?”

Phillipa shook her head. “They let Simon in tonight, just before he went off-shift. He visited on the pretext of checking on the stasis chamber they’ve borrowed from the infirmary. But that’s allthey’d let him do. For me, they wouldn’t even open up the door to their quarters.”

Shar’s quarters,Ro thought. The rooms where the despondent Thriss had taken her own life. Where two of her soul mates still maintained a vigil, two long weeks later.

“Do you feel they’re dangerous?” Ro said at length, recalling how Anichent had charged at her, lunacy shining in his cold gray eyes.

“Anyone that overwrought always has the potential to be dangerous, at least to himself. But when the person in question is an Andorian, that makes things even more volatile.”

“In other words, I’d better maintain the guards I posted outside Shar’s quarters.”

Phillipa nodded, but looked apprehensive. “As long as they stay out in the corridor, and a few doors away. Like I said, those antennae can be pretty sensitive, especially to the EM fields produced by phasers. That said, my sense is that they’re likely to refrain from any further, ah, demonstrative behaviors.”

“What makes you say that?”

“Because they have each other. And grief shared is grief halved.”

Ro wanted to believe that. But she understood only too well the impulse to spread grief around, the way nerakflowers scattered themselves on the wind beside the River Glyrhond.

“Maybe I should make another stab at talking with them,” she said, recovering her padd and walking toward the security office door with it. Phillipa followed her out into the corridor, her brow scored with consternation.

“I don’t think that’s such a great idea, Ro.”

Ro stopped in front of the turbolift just as its doors opened. “You just finished explaining that they wouldn’t talk to you because you’ve got too much empathy.”

Ro stepped inside, treading on Phillipa’s response as she moved. “That’s an accusation nobody’s ever made about me.”

The turbolift doors quietly closed on Phillipa’s wordless you’ll-be-sorryexpression.

Standing in the habitat ring, Ro looked down the corridor to her left. Four doors away, Corporal Hava stood at parade rest, his hand near the butt of his phaser. Ro turned her head to the right, where Sergeant Shul Torem stood quietly an equal distance away in the opposite direction. Somehow, the grizzled veteran managed to appear both relaxed and vigilant.

Clutching a padd tightly in her right hand, Ro was uncomfortably aware of her own weapon’s conspicuous absence as she pressed the door chime before her.

“Go away.”

It was Dizhei’s voice. Though the gray duranium door muffled it considerably, Ro could hear the underlying rawness.

“Go away. Whoever you are.”

“It’s Lieutenant Ro,” Ro said, relieved that Anichent hadn’t been the one to answer the door. “I’m here on official business.”

A long beat passed before Dizhei spoke again. She sounded calmer now, though she seemed to be trying very hard to rein in her emotions. “Please, Lieutenant. We do not desire any visitors right now. Anichent and I will contact you. Later. When we are ready. After Shar returns.”

Ro was quickly growing tired of conversing through a metal door. “Shar isn’t due back from the Gamma Quadrant for several more weeks. I understand your grief, Dizhei. And you already know that I respect your people’s funerary customs. But I have regulations to follow and reports to file. Certain things need to be resolved, sooner rather than later.”

The heavy gray door stood as mute and inert as a Sh’dama-era stone monolith.

After nearly half a minute, Ro broke the silence. “How does Anichent feel about speaking with me? I’ll only need a few minutes of his time.”

More silence. Ro’s spine suddenly felt as though it had been dipped in liquid nitrogen as a thought occurred to her: What if Anichent wasn’t merely being reclusive?

Perhaps he couldn’tcome to the door.

“Dizhei? Open the door now. Please. I really need to speak with Anichent.”

Nothing.

Ro gestured toward both guards, who responded by quietly drawing their weapons. She hated that things were coming to this. But she had to know what was going on behind that metal slab.

Tapping her combadge, Ro said, “Computer, security override at the personal quarters of Ensign Thirishar ch’Thane. Authorization Ro-Gamma-Seven-Four.”

The door slid aside and Ro entered the room, holding herself bowstring-taut. Hava and Shul followed a few paces behind her.

The air was moist, and hot as summertime in Musilla Province. The darkness of the small main room was broken by the flames that danced atop a pair of tall, pungent-smelling candles. Countless bejeweled pinpoints adorned the emptiness beyond the large oval window. Between the candles, at the room’s spinward edge, stood a bier surrounded by the faint bluish glow of a large stasis chamber. Thriss’s corpse, clad in a simple white gown, lay in state atop the bier, per Andorian custom. The pale cerulean light that bathed the body gave it an oddly lifelike aspect, as though Thriss were merely sleeping and might be awakened by an errant footfall or a creaking deckplate.

In spite of herself, Ro made a special effort to be silent as she stepped toward the two figures who knelt before the bier. She stood for a long moment behind them, allowing her eyes to adjust to the wan candlelight and the room’s fluttering, crepuscular shadows.

She watched Anichent and Dizhei in profile, observing that they both seemed to be in a deep meditative state. They looked tired and gaunt, their nondescript Andorian prayer robes draped over their bodies like sails. Ro couldn’t determine whether they had continued cutting their flesh, as they had begun doing immediately after Thriss’s death. Their eyes were closed, their limp antennae draped back across disheveled white hair. Neither of them acknowledged her presence. Ro couldn’t tell whether they were indeed sharing their grief, or if each was trapped in some solitary emotional purgatory.

Thanks to a briefing Phillipa had given her, Ro felt she knew at least the basics of Andorian biology and funerary customs. Because their species’ reproduction depended upon all four members of a bond, the death of any one of them was a terrible blow to the survivors—and often produced some extreme grieving rituals. Obviously, neither Dizhei nor Anichent seemed able either to let go of their lost love or to go on with their lives. They wouldn’t prepare Thriss’s body for interment or even allow a proper autopsy. Before any of those things could happen, all three surviving members of their sundered marriage quad had to assemble in shared grief beside Thriss’s body. Therefore, they were determined to await Shar’s return, consuming only water—and interacting with no one—until that day.

No matter how far off that day might be.

If not for their tangled white manes, blue skin, and antennae, Dizhei and Anichent might have been a pair of Bajoran religious acolytes, beseeching the Prophets for guidance. Ro had always felt somewhat detached from—not to mention bemused by—the fervent religious beliefs of many of her fellow Bajorans. Her father’s murder at the hands of Bajor’s Cardassian oppressors had taught her that piety and a concussion grenade nearly always got better results than did piety alone.

The self-abnegation on display before her stirred up some of the conflicted feelings the Bajoran faith frequently roused within her. And even though she knew that it was useless to judge another culture’s practices against those of her own, the sight roused an even deeper, more fundamental sentiment.

It made her angry.

She brought her padd down against the top of a low table, hard. In the silence of the room, the noise sounded like a thunderclap.

Dizhei started as though she’d been dealt a physical blow. She turned toward Ro, glowering. Ro could hear Shul and Hava moving in behind her, ready to react. But Dizhei did not rise to her feet.

“Is this intrusion a sample of what we can expect from Bajor after it enters the Federation?” Dizhei said, fairly hissing the words. Gone was the veneer of amiability Ro had noted when the Andorian first came aboard the station several weeks ago.

Ro picked up her padd, ignoring the comment. “I apologize for barging in, Dizhei. But I had reason to suspect that Anichent might be in danger.”

Dizhei laughed, a harsh sound that contained no humor. “Because we Andorians are such a violently emotional lot, no doubt.”

“I never said that,” Ro said. She clutched the padd in a death grip.

Dizhei’s gaze softened as she seemed to consider her next words carefully before uttering them. “You didn’t have to, Lieutenant. We both know it’s true.”

Anichent lifted his head then, as though it were supporting an enormous weight. Still kneeling, he gazed up at Ro, who felt her legs and shoulders tensing in an involuntary fight-or-flight reaction. Her pulse quickened, and she heard a sharp intake of breath from Hava, who now stood beside her.

“She saw it so clearly,” Anichent whispered, the despondence behind his words almost palpable. “More clearly than any of the rest of us ever could have.”

Ro knew that he could only be referring to Thriss. “What did she see?”

Before Anichent could respond, Dizhei cut him off with a harsh Andorii monosyllable. Anichent lowered his head and closed his eyes once again, as though lost in prayer or meditation.

Dizhei fixed her eyes on Ro’s. “Your men can lower their weapons,” she said quietly. “Anichent can barely move, let alone attack you.”

“Stay alert,” Ro told Shul, who grunted an acknowledgment. To Dizhei she said, “I really hate to be indelicate, but without an autopsy, station regulations require me to log an official statement from Thriss’s closest available family members. Councillor zh’Thane doesn’t qualify, but as members of Thriss’s bondgroup, either of you does. I’m sorry, but this is the only way I can officially close the matter. It’ll take maybe ten minutes. Then we’ll be gone, and won’t bother you anymore.”

Dizhei looked incredulous and angry. “Surely you have more important things to do with your time right now than to harass us.”

“As a matter of fact, I do,” Ro said, feeling her own pique beginning to rise with the inevitability of gravity. “This station is going to be swarming with Federation and Bajoran VIPs over the next few days. I’ve got to stage-manage the Federation signing ceremony, and it’s going to be a security nightmare as it is. I can’t afford to have a case like this still open and unresolved here with all of that going on.”

“I see,” Dizhei said, her ice-blue eyes narrowing, her antennae moving forward as though searching for something to impale.

Tamping down her anger, Ro raised a hand in supplication. “Look. I know this is a terrible time for you. But surely two weeks has been time enough—”

“Time,” Anichent said in a voice rough enough to strike sparks, his speech slurring as he raised his head again. “What is time when there is no future?”

Ro approached Anichent more closely, watching as the candlelight flickered in his gray eyes. Gone was the upbeat, sharp-witted intellectual she’d observed weeks ago. ThisAnichent was a mere husk. A vacant, hollowed-out revenant.

“You’ve drugged him,” Ro said to Dizhei. It wasn’t a question.

Dizhei nodded. “To save his life.”

“We’ve got to get him to the infirmary.”

“No. I know the Andorian pharmacopoeia better than your Dr. Tarses does. Anichent is far safer here. Where I can watch over him.”

All at once, Ro understood. Anichent wouldbe safer in a place where he wasn’t likely to come out of his drug trance at an inopportune time. In a place where he couldn’t succumb to the temptation to throw himself willfully into death’s jaws. A semantically twisted phrase she’d encountered once during a Starfleet Academy history course sprang to her mind.

Police-assisted suicide.

The remainder of Ro’s anger dissipated as she considered the likely source of the Andorian people’s violence. It wasn’t innate, as with the Jem’Hadar. Or indoctrinated, as with the Klingons. Instead, it was born of pain.

I understand pain.

“Stand down,” Ro said to the guards. “Dismissed.” Hava didn’t need to be told twice, but Shul required a moment’s persuasion before he, too, departed.

“Do you truly believe that you understand now?” Dizhei said after she and Ro were essentially alone. Anichent had retreated once again into his drugged stupor.

Dizhei rose to her feet and approached Ro, who managed to keep from flinching, but steeled herself against the possibility of another violent outburst.

Ro nodded cautiously. “He’s lost hope.”

Dizhei responded with a barely perceptible shake of the head. She spoke softly, as though fearing that the oblivious Anichent might overhear. “No. It’s more profound than even that, Lieutenant. He believes that hope itself no longer exists. That Thriss’s death is merely an augury for our entire species.”

“There’s always hope,” Ro said, without convincing even herself.

“Looming extinction has a way of snuffing out hope,” Dizhei said.

My son has also ravaged the lives of Anichent and Dizhei,zh’Thane had said. Ro recalled the councillor’s explanation of how Andorian marriage quads were groomed for their unions from childhood, and how few years the young adult bondmates had to produce offspring. It came to her then that the odds of Dizhei and Anichent finding a replacement for Thriss might be remote—perhaps impossibly so.

She saw it so clearly,Anichent had said. Ro knew that utter, bleak despair was what Thriss must have seen. Not just for herself, but for her entire world.

And here I am, barging in and interrogating them about her. Good job, Laren.Ro felt as though she’d just kicked a helpless Drathan puppy lig.

Dizhei resumed speaking. “Anichent truly believes that we are dying as a species because of our complicated reproductive processes. I tell you this only because I know that Shar considers you a good friend. He trusts you.”

Ro felt the warning sting of tears in her eyes, but held them back by sheer force of will.

“It’s mutual,” Ro said. “We have a number of things in common.” We’re both outsiders who don’t share our secrets with very many others. And especially not our fears.

Dizhei’s antennae slackened once again. She studied Ro in silence, obviously waiting for her to make the next move.

“Do you believe that Anichent is right?” Ro said softly.

Dizhei closed her eyes and sighed, composing her thoughts before speaking. “There are times when I’m not at all certain that he’s wrong. But I can’t afford to let myself think that way often. If I do, then the rest of us will be lost, along with whatever tiny chance remains of finding another bondmate to replace Thriss in time to produce a child.”

Dizhei straightened as though buoyed by her own words. Her bearing suddenly became almost regal. This is how Charivretha zh’Thane must have looked thirty years ago, Ro thought.

“I will watch over Thriss until Shar returns, as our customs demand. And I will do the same for Anichent, to keep him from following her over the precipice. Even if doing so occupies every moment of every day until Shar returns. Even if it kills me.”

Ro considered the despair that had stalked so many of her friends and loved ones. Few, if any, of her intimates had ever had such sound reasons for despondence as bond-sundered Andorians. These were people for whom complex reproductive biology was the single defining attribute of their lives. After suddenly losing that capability, how could one notsuccumb to hopelessness? Ro felt an uncharacteristic but irresistible urge to get a drink. Or perhaps several.

“Now, about that report you wanted,” Dizhei said, her antennae probing forward as though sniffing the air.

Ro shut down her padd and lowered it. A bead of sweat traced a leisurely path between her shoulder blades.

“It will wait,” she said, suddenly overwhelmed by the enormity of Dizhei’s burden—and by Anichent’s hopelessness. Routine police work now seemed utterly trivial by comparison. “Please forget I asked. And forgive me.”

Ro hastily excused herself, then stepped back into the cool corridor before Dizhei could see the tears she could no longer restrain.

Halfway through her third glass of spring wine, Ro felt considerably calmer.

“Whoa there,” said Treir, who sat across the table in Ro’s dimly lit booth. She eyed the two empty wine-glasses significantly. “Maybe you’d better consider slowing down to sublight speed, Lieutenant.”

“I’m off duty at the moment,” Ro said, swirling her wine. This vintage was a little drier than she was used to, but still serviceable. “And sometimes the best way to handle your troubles is to drown them.”

The Orion woman offered a wry smile, her teeth a dazzling white against her jade-green skin, much of which was displayed by the strategically placed gaps in her designer dabo girl costume. She raised her warp core breach, a beverage Ro had never been able to distinguish from industrial solvent, in a toast. Although Treir’s drinking vessel dwarfed Ro’s, in the viridianskinned woman’s large but graceful hands it was proportionally the same size.

“To the drowning of troubles,” Treir said, and they both drank. “Or at least to taking them out for a nice, brisk swim. Let’s see, now. Which troubles are in most urgent need of drowning? There’s the Andorians that have taken up residence in Ensign ch’Thane’s quarters. And the signing ceremonies for Bajor’s entry into the Federation.”

Ro offered a wan smile as she raised her glass to her lips. “You should talk to Lieutenant Commander Matthias about apprenticing in the counseling business.”

Ro reflected on how much their relationship had changed since she and Quark had rescued Treir from the employ of the Orion pirate Malic a few months back. There was obviously a great deal more to Treir than her brassy exterior had initially led Ro to believe.

Treir glanced quickly over her shoulder, then returned her attention to Ro, to whom she spoke in a conspiratorial whisper. “Oh, and don’t forget the single most horrific item on the entire dreary list of troubles to be drowned—there’s still the matter of that second date my boss somehow tricked you into.”

Ro nearly spit her wine across the table. Lately she’d been so wrapped up in station business that she’d completely forgotten.

“I heard that!” The voice belonged to Quark, though it took Ro a moment to zero in on his exact whereabouts. Then she saw that the owner and proprietor of DS9’s principle hospitality establishment was standing three booths away, beside the small group of Terrellians whose drinks he had just delivered.