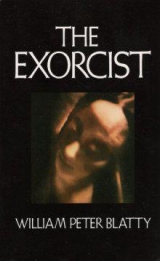

Текст книги "The Exorcist"

Автор книги: William Peter Blatty

Жанр:

Мистика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

"Willie what?"

"Oh, well, nothing." She, shrugged as she tugged her gaze away from the manservant's brawny back. The oven was clean, she had noticed. Why was Karl still polishing?

She reached for a cigarette. Kinderman lit it.

"So then only your daughter would know when Dennings left the house."

"It was really an accident?"

"Oh, of course. It's routine, Miss MacNeil, its routine.

Mr. Dennings wasn't robbed and he had no enemies, none that we know of, that is, in the District."

Chris darted a momentary glance to Karl but then shifted it quickly bade to Kinderman. Had he noticed? Apparently not. He was fingering the sculpture.

"It's got a name, this kind of bird; I can't think of it. something." He noticed Chris staring and looked vaguely embarrassed. "Forgive me, you're busy. Well, a minute and we're done. Now your daughter, she would know when Mr. Dennings left?"

"No, she wouldn't. She was heavily sedated."

"Ah, dear me, a shame, a shame." His droopy eyelids seeped concern. "It's serious?"

"Yes, I'm afraid it is."

"May I ask...?" he probed with a delicate gesture.

'We still don't know."

"Watch out for drafts," he cautioned firmly.

Chris looked blank.

"A draft in the winter when a house is hot is a magic carpet for bacteria. My mother used to say that. Maybe that's folk myth. Maybe." He shrugged. "But a myth, to speak plainly, to me is like a menu in a fancy French restaurant: glamorous, complicated camouflage for a fact you wouldn't otherwise swallow, like maybe lima beans," he said earnestly.

Chris relaxed. The shaggy dog padding fuddled through cornfields had returned.

"That's hers, that's her room"–he was thumbing toward the ceiling–"with that great big window looking out on these steps?"

Chris nodded.

"Keep the window closed and she'll get better."

"Well, it's always closed and it's always shuttered" Chris said as he dipped a pudgy hand in the inside pocket of his jacket.

"She'll get better," he repeated sententiously. "Just remember, 'An ounce of prevention...' "

Chris drummed her fingertips on the tabletop again.

"You're busy. Well, we're finished. Just a note for the record–routine–we're all done."

From the pocket of the jacket he'd extracted a crumpled mimeographed program of a high-school production of Cyrano de Bergerac and now groped in the pockets of his coat, where he netted a toothmarked yellow stub of a number 2 pencil, whose point had the look of having been sharpened with the blade of a scissors. He pressed the program flat on the table, brushing out the wrinkles. "Now just a name or two," he puffed. "That's Spencer with a c?"

"Yes, c."

"A c," he repeated, writing the name in a margin of the program. "And the housekeepers? John and Willie...?"

"Karl and Willie Engstrom."

"Karl. That's right, it's Karl. Karl Engstrom." He scribbled the names in a dark, thick script. "Now the times I remember," he told her huskily, turning the program around in search of white space. "Times I–Oh. Oh, no, wait. I forgot. Yes, the housekeepers. You said they got home at what time?"

'I didn't say. Karl, what time did you get in last night?" Chris called to him.

The Swiss turned around, his face inscrutable. "Exactly nine-thirty, madam."

"Yeah, that's right, you'd forgotten your key. I remember I looked at the clock in the kitchen when you rang the doorbell."

"You saw a good film?" the detective asked Karl. "I never go by reviews," he explained to Chris in a breathy aside. "It's what the people think, the audience."

"Paul Scofield in Lear" Karl informed the detective.

"Ah, I saw that; that's excellent. Excellent. Marvelous "

"Yes, at the Crest," Karl continued. "The six-o'clock showing. Then immediately after I take the bus from in front of the theater and–"

"Please, that's not necessary," the detective pro-tested with a gesture. "Please."

"I don't mind."

"If you insist."

"I get off at Wisconsin Avenue and M Street. Nine-twenty, perhaps. And then I walk to the house."

"Look, you didn't have to tell me," the detective told him, "but anyway, thank you, it was very considerate. You liked the film?"

"It was excellent."

"Yes, I thought so too. Exceptional. Well, now..." He turned back to Chris and to scribbling on the program. "I've wasted your time, but I have a job." He shrugged. "Well, only a moment and finished. Tragic... tragic..." he breathed as he jotted down fragments in margins. "Such a talent. And a man who knew people, I'm sure: how to handle them. With so many elements who could make him look good or maybe make him look bad–like the cameraman, the sound man, the composer, whatever.... Please correct me if I'm wrong, bud it seems to me nowadays a director of importance has also to be almost a Dale Carnegie. Am I wrong?"

"Oh, well, Burke had a temper," Chris sighed.

The detective repositioned the program. "Ah, well, maybe so with the big shots. People his size." Once again he was scribbling. "But the key is the little people, the menials, the people who handle the minor details that if they didn't handle right would be major details. Don't you think?"

Chris glanced at her fingernails and ruefully shook her head. "When Burke let fly, he never discriminated," she murmured with a weak, wry smile. "No, sir. It was only when he drank, though."

"Finished. We're finished." Kinderman was dotting a final i. "Oh, no, wait," he abruptly remembered. "Mrs. Engstrom. They went and came together?" He was gesturing toward Karl.

"No, she went to see a Beatles film," Chris answered just as Karl was turning to reply. "She got in a few minutes after I did."

"Why did I ask that? It wasn't important." He shrugged as he folded up the program and tucked it away in the pocket of his jacket along with the pencil. "Well, that's that. When I'm back in the office, no doubt I'll remember something I should have asked. With me, that always happens. Oh, well, I could call you," he puffed, standing up.

Chris rose along with him.

"Well, I'm going out of town for a couple of weeks," she said.

"It can wait" he assured her. "It can wait." He was staring of the sculpture with a smiling fondness. "Cute. So cute," he said. He'd leaned over and picked it up and was rubbing his thumb along is beak.

Chris bent over to pick up a thread on the kitchen floor.

"Have you got a good doctor?" the detective asked her. "I mean for your daughter."

He replaced the figure and began to leave. Glumly Chris followed, winding the thread around her thumb.

"Well, I've sure got enough of them," she murmured. "Anyway, I'm checking her into a clinic that's supposed to be great at doing what you do, only viruses."

"Let's hope they're a great deal better. It's out of town, this clinic?"

"Yes, it is."

"It's a good one?"

"We'll see."

"Keep her out of the draft."

They had reached the front door of the house. He put a hand on the doorknob. "Well, I would say that it's been a pleasure, but under the circumstances..." He bowed his head and shook it. "I'm sorry. Really. I'm terribly sorry."

Chris folded her arms and looked down at the rug. She nodded briefly.

Kinderman opened the door and stepped outside. As he turned to Chris, he was putting on his hat. "Well, good luck with your daughter."

"Thanks." She smiled wanly. "Good luck with the world."

He nodded with a gentle warmth and sadness, then waddled away. Chris watched as he listed toward a waiting squad car parked near the corner in front of a fire hydrant. He flung up a hand to his hat as a shearing wind sprang sharp from the south. The hem of his coat flapped. Chris closed the door.

When he'd entered the passenger side of the squad car, Kinderman fumed and looked back at the house. He thought he saw movement at Regan's window, a quick, lithe figure flashing to the side and out of view. He wasn't sure. He'd seen it peripherally as he'd turned. But he noted that the shutters were open. Odd. For a moment he waited. No one appeared. With a puzzled frown, the detective turned and opened the glove compartment, extracting a small brown envelope and a penknife. Unclasping the smallest of the blades of the knife, he held his thumb inside the envelope and surgically scraped paint from Regan's sculpture from under his thumbnail. When he had finished and was sealing the envelope, he nodded to the detective-sergeant behind, the wheel. They pulled away.

As they drove down Prospect Street, Kinderman pocketed the envelope. "take it easy," he captioned the sergeant, glancing at the traffic building up ahead. "This is business, not pleasure." He rubbed at his eyes with weary fingers. "Ah, what a life," he sighed. "What a life."

Later, that evening, while Dr. Klein was injecting Regan with fifty milligrams of Sparine to assure her tranquillity on the journey to Dayton, Lieutenant Kinderman stood brooding in his office, palms pressed flat atop his desk as he pored over fragments of baffling data. The narrow beam of an ancient desk lamp flared on a clutter of scattered reports. There was no other light. He believed that it helped him narrow the focus of concentration.

Kinderman's breathing labored heavy in the darkness as his glance flitted here; now there. Then he took a deep breath and shut his eyes. Mental Clearance Sale! he instructed himself, as he did whenever he wished to tidy his brain for a fresh point of view: Absolutely Everything Must Go!

When he opened his eyes, he examined the pathologist's report on Dennings: ... tearing of the spinal cord with fractured skull and neck, plus numerous contusions, lacerations, and abrasions; stretching of the neck skin; ecchymosis of the neck skin; shearing of platysma, sternomastoid, splenius, trapezius and various smaller muscles of the neck, with fracture of the spine and of the vertebrae and shearing of both the anterior and posterior spinous ligaments....

He looked out a window at the dark of the city. The Capitol dome light glowed. The Congress was working late. He shut his eyes again, recalling his conversation with the District pathologist at eleven-fifty-five on the night of Denning's death.

"It could have happened in the fall?"

"No, it's very unlikely. The sternomastoids and the trapezius muscles alone are enough to prevent it. Then you've also got the various articulations of the cervical spine to be overcome as well as the ligaments holding the bores together."

"Speaking plainly, however, is it possible?"

"Well, of course, he was drunk and these muscles were doubtless somewhat relaxed. Perhaps if the force of the initial impact were sufficiently powerful and–"

"Falling maybe twenty or thirty feet before he hit?"

"Yes, that, and if immediately after impact his head got stuck in something; to other words, if there were immediate interference with the normal rotation of the head and body as a unit, well maybe–I say just maybe–you could get this result."

"Could another human being have done it?"

"Yes, but he'd have to be an exceptionally powerful man."

Kinderman had checked Karl Engstrom's story regarding his whereabouts at the time of Denning's death. The show times matched, as did the schedule that night of a D. C. Transit bus. Moreover, the driver of the bus that Karl had claimed he had boarded by the theater went off duty at Wisconsin and M, where Karl had stated he alighted at approximately twenty minutes after nine. A change of drivers had taken place, and the off-duty driver had logged the time of his arrival at the transfer point: precisely nine-eighteen.

Yet on Kinderman's desk was a record of a felony charge against Engstrom on August 27, 1963, alleging he had stolen a quantity of narcotics over a period of months from the home of a doctor in Beverly Hills where he and Willie were then employed.

... born April 20, 1921, in Zurich, Switzerland. Married to Willie nee Braun September 7, 1941. Daughter, Elvira, born New York City, January 11, 1943, current address unknown. Defendant...

The remainder the detective found baffling: The doctor, whose testimony was sine qua non for successful prosecution, abruptly–and without any explanation–dropped the charges.

Why would he done so?

The Engstrom were hired by Chris MacNeil only two months later, which meant that the doctor had given them a favorable reference.

Why would he do so?

Engstrom had certainly pilfered the drugs, and yet a medical examination at the time of the charge had failed to yield the slightest sign that the man was an addict, or even a user.

Why not?

With his eyes still closed, the detective softly recited Lewis Carroll's "Jabberwocky": " 'Twas brillig and the slithy tones..." Another of his mind-clearing tricks.

When he'd finished reciting, he opened his eyes and fixed his gaze on the Capitol rotunda, trying to keep his mind a blank. But as usual, he found the task impossible. Sighing, he glanced at the police psychologist's report on the recent desecrations at Holy Trinity: "... statue... phallus... human excrement... Damien Karras," he had underscored in red. He breathed in the silence and then reached for a scholarly work on witchcraft, turning to a page he had marked with a paper clip: Black Mass... a form of devil worship, the ritual, in the main, consisting of (1) exhortation (the "sermon") to performance of evil among the community, (2) coition with the demon (reputedly painful, the demon's penis invariably described as "icy cold"), and (3) a variety of desecrations that were largely sexual in nature. For example, communion Hosts of unusual size were prepared (compounded of flour, feces, menstrual blood and pus), which then were slit and used as artificial vaginas with which the priests would ferociously copulate while raving that they were ravishing the Virgin Mother of God or that they were sodomizing Christ. In another instance of such practice, a statue of Christ was inserted deep in a girl's vagina while into her anus was inserted the Host, which the priest then crushed as he shouted blasphemies and sodomized the girl. Life-sized images of Christ and the Virgin Mary also played a frequent role in the ritual. The image of the Virgin, for example–usually painted to give her a dissolute, sluttish appearance–was equipped with breasts which cultists sucked, and also a vagina into which the penis might be inserted. The statues of Christ were equipped with a phallus for fellatio by both the men and the women, and also for insertion into the vagina of the women and the anus of the men. Occasionally, rather than an image, a human figure was bound to a cross and made to function in place of the statue, and upon the discharge of his semen it was collected in a blasphemously consecrated chalice and used in the making of the communion host, which was destined to be consecrated on an altar coveted with excrement. This– Kinderman flipped the pages to an underlined paragraph dealing with ritualistic murder. He read it slowly, nibbling at the pad of an index finger, and when he had finished he frowned at the page and shook his head. He lifted a brooding glance to the -lamp. He flicked it out. He left his office and drove to the morgue.

The young attendant at the desk wan munching at a ham and cheese sandwich on rye, and brushed the crumbs from a crossword puzzle as Kinderman approached him.

"Dennings," the detective whispered hoarsely.

The attendant nodded, filling in a five-letter horizontal, then rose with his sandwich and moved down the hall.

Kinderman followed him, hat in hand, followed faint scent of caraway seed and mustard to rows of refrigerated lockers, to the dreamless cabinet used for the filing of sightless eyes.

They halted at locker 32, The expressionless attendant slid it out. He bit at his sandwich, and a fragment of mayonnaise-speckled crust fell lightly to the shroud.

For a moment Kinderman stared down; then, slowly and gently, he pulled back the sheet to expose what he'd seen and yet could not accept.

Burke Dennings' head was turned completely around, facing backward.

CHAPTER FIVE

Cupped in the warm, green hollow of the campus, Damien Karras, jogged alone around an oval, loamy track in khaki shorts and a cotton T-shit drenched with the cling of healing sweat. Up ahead, on a hillock, the lime-white dome of the astronomical observatory pulsed with the beat of his stride; behind him, the medical school fell away with churned-up shards of earth and care.

Since release from his duties, he came here daily, lapping the miles and chasing sleep. He had almost caught it; almost eased the clutch of grief that gripped at his heart like a deep tattoo. It held him gentler now.

Twenty laps...

Much gentler.

More! Two more!

Much gentler...

Powerful leg muscles blooded and stinging, rippling with a long and leonine grace, Karras thumped around a turn when he noticed someone sitting on a bench to– the side where he'd laid out his towel, sweater and pants: a middle-aged man in a floppy overcoat and pulpy, crushed felt hat. He seemed to be watching him. Was he? Yes... head turning as Karras passed.

The priest accelerated, digging at the final lap with pounding strides that jarred the earth, then he slowed to a panting, gulping walk as he passed the bench without a glance, both hands pressed light to his throbbing sides. The heave of his rock-muscled chest and shoulders stretched his T-shirt, distorting the stenciled word PHILOSOPHERS inscribed across the front in once-blade letters now faded to a hint by repeated washings.

The man in the overcoat stood up and began to approach him.

"Father Karras?" Lieutenant Kinderman called hoarsely.

The priest turned around and nodded briefly, squinting into sunlight, waiting for Kinderman to reach him, then beckoned him along as once again he began to move. "Do you mind? I'll cramp," he panted. "Yes, of course." the detective answered, nodding with a wincing lack of enthusiasm as be tucked his hands into his pockets. The walk from the parking lot had tired him.

"Have–have we met?" asked the Jesuit.

"No, Father. No, but they said that you looked like a boxer; some priest at the residence hall; I forget." He was tugging out his wallet. "So bad with names."

"And yours?"

"William Kinderman, Father." He flashed his identification. "Homicide."

"Really?" Karras scanned the badge and identification card with a shining, boyish interest. Flushed and perspiring, his face had an eager look of innocence as he turned to the waddling detective. "What's this about?"

"Hey, you know something, Father?" Kinderman answered, inspecting the Jesuit's rugged features. "It's true, you do look like a boxer. Excuse me; that scar, you know, there by your eye?" He was pointing. "Like Brando, it looks like, in Waterfront, just exactly Marlon Brando. They gave him a scar"–he was illustrating, pulling at the corner of his eye–"that made his eye look a little bit closed, just a little, made him look a little dreamy all the time, always sad. Well, that's you," he said, pointing. "You're Brando. People tell you that, Father?"

"No, they don't."

"Ever box?"

"Oh, a little."

"You're from here in the District?"

"New York."

"Golden Gloves. Am I right?"

"You just made captain." Karras smiled. "Now what can I do for you?"

"Walk a little slower, please. Emphysema." The detective was gesturing at his throat.

"Oh, I'm sorry." Karras slowed his pace.

"Never mind. Do you smoke?"

"Yes, I do."

"You shouldn't."

"Well, now tell me the problem."

"Of course; I'm digressing. Incidentally, you're busy?" the detective inquired. "I'm not interrupting?"

"Interrupting what?" asked Karras, bemused.

"Well, mental prayer, perhaps."

"You will make captain." Karras smiled cryptically.

"Pardon me, I missed something?"

Karras shook his head; but the smile lingered. "I doubt that you ever miss a thing," he remarked. His sidelong glance toward Kinderman was sly and warmly twinkling.

Kinderman halted and mounted a massive and hopeless effort at looking befuddled, but glancing at the Jesuit's crinkling eyes, he lowered his head and chuckled ruefully. "Ah, well. Of course... of course... a psychiatrist. Who am I kidding?" He shrugged. "Look, it's habit with me, Father. Forgive me. Schmaltz–that's the Kinderman method: pure schmaltz. Well, I'll stop and tell you straight what it's all about."

"The desecrations," Karras said, nodding.

"So I wasted my schmaltz, the detective said quietly.

"Sorry"

"Never mind, Father; that I deserved. Yes, the things in the church," he confirmed. "Correct. Only maybe something else besides, something serious."

"Murder?"

"Yes. kick me again, I enjoy it."

"Well, Homicide Division." The Jesuit shrugged.

"Never mind, never mind, Marlon Brando; never mind.

People tell you for a priest you're a little bit smart-ass?"

"Mea culpa," Karras murmured. Though he was smiling, he felt a regret that perhaps he'd diminished the man's self esteem. He hadn't meant to. And now he felt glad of a chance to express a sincere perplexity. "I don't get it, though," he added, taking care that he wrinkled his brow. "What's the connection?"

"Look, Father, could we keep this between us? Confidential? Like a matter of confession, so to speak?"

"Of course." He was eyeing the detective earnestly. "What is it?"

"You know that director who was doing the film here, Father? Burke Dennings?"

"Well, I've seen him."

"You've seen him." The detective nodded. "You're also familiar with how he died?"

"Well, the papers..." Karras shrugged again.

"That's just part of it."

"Oh?"

"Only part of it. Part. Just a part. Listen, what do you know on the subject of witchcraft?"

"What?"

"Listen, patience; I'm leading up to something. Now witchcraft, please–you're familiar?"

"A little."

"From the witching end, not the hunting."

"Oh, I once did a paper on it" Karras smiled. "The psychiatric end."

"Oh, really? Wonderful! Great! That's a bonus. A plus. You could help me a lot, a lot more than I thought. Listen, Father. Now witchcraft..."

He reached up and gripped at the Jesuit's arm as they rounded a turn and approached the bench. "Now me, I'm a layman and, plainly speaking, not well educated. Not formally. No. But I read. Look; I know what they say about self-made men, that they're horrible examples of unskilled labor. But me, I'll speak plainly, I'm not ashamed. Not at all, I'm–" Abruptly he arrested the flow, looked down and shook his head. "Schmaltz. It's habit. I can't stop the schmaltz. Look, forgive me; you're busy."

"Yes, I'm praying."

The Jesuit's soft delivery had been dry and expressionless. Kinderman halted for a moment and eyed him. "You're serious? No."

The detective faced forward again and they walked. "Look, I'll come to the point: the desecrations. They remind you of anything to do with witchcraft?"

"Maybe. Some rituals used in Black Mass."

"A-plus. And now Dennings–you read how he died?"

"In a fall"

"Well, I'll tell you, and–please–confidential!"

"Of course."

The detective looked suddenly pained as he realized that Karras had no intention of stopping at the bench. "Do you mind?" he asked wistfully.

"What?"

"Could we stop? Maybe sit?"

"Oh, sure." They began to move back toward the bench.

"You won't cramp?"

"No, I'm fine now."

"You're sure?"

"I'm fine."

"All right, all right, if you insist."

"You were saying?"

"In a second, please, just one second."

Kinderman settled his aching bulk on the bench with a sigh of content. "Ah, better, that's better," he said as the Jesuit picked up his towel and wiped his perspiring face. "Middle age. What a life."

"Burke Dennings?-"

"Burke Dennings, Burke Dennings, Burke Dennings..." The detective was nodding down at his shoes. Then he glanced up at Karras. The priest was wiping the back of his neck. "Burke Dennings, good Father, was found at the bottom of that long flight of steps at exactly five minutes after seven with his head turned completely around and backward."

Peppery shouts drifted muffled from the baseball diamond where the varsity team held practice. Karras stopped wiping and held the lieutenant's steady gaze. "It didn't happen in the fall?" he said at last.

"Sure, it's possible." Kinderman shrugged. "But..."

"Unlikely," Karras brooded.

"And so what comes to mind in the contest of witchcraft?"

The Jesuit sat down slowly, looking pensive. "Well," he said finally, "supposedly demons broke the necks of witches that way. At least, that's the myth."

"A myth?"

"Oh, largely," he said, turning to Kinderman. "Although people did die that way, I suppose: likely members of a coven who either defected or gave away secrets. That's just a guess. But I know it was a trademark of demonic assassins."

Kinderman nodded. "Exactly. Exactly. I remembered the connection from a murder in London. That's now. I mean, lately, just four or five years ago, Father. I remembered that I read it in the papers."

"Yes, I read it too, but I think it turned out to be some sort of hoax. Am I wrong?"

"No, that's right, Father, absolutely right. But in this case, at least, you can see some connection, maybe, with that and the things in the church. Maybe somebody crazy, Father, maybe someone with a spite against the Church. Some unconscious rebellion, perhaps..."

"Sick priest," murmured Karras. "That it?"

"Listen, you re the psychiatrist, Father; you tell me."

"Well, of course, the desecrations are clearly pathological," Karras said thoughtfully, slipping on his sweater. "And if Dennings was murdered–well, I'd guess that the killer's pathological too."

"And perhaps had some knowledge of witchcraft?"

"Could be."

"Could be," the detective grunted. "So who fits the bill, also lives in the neighborhood, and also has access in the night to the church?"

"Sick priest," Karras said, reaching out moodily beside him to a pair of sun-bleached khaki pants.

"Listen, Father, this is hard for you–please!–I understand. But for priests on the campus here, you're the psychiatrist, Father, so–"

"No, I've had a change of assignment."

"Oh, really? In the middle of the year?"

"That's the Order," Karras shrugged as he pulled on the pants.

"Still, you'd know who was sick at the time and who wasn't, correct? I mean, this kind of sickness. You'd know that."

"No, not necessarily, Lieutenant. Not at all. It would only be an accident, in fact, if I did. You see, I'm not a psychoanalyst. All I do is counsel. Anyway," he commented, buttoning his trousers, "I really know of no one who fits the description."

"Ah, yes; doctor's ethics. If you knew. You wouldn't tell."

"No, I probably wouldn't."

"Incidentally–and I mention it only in passing–this ethic is lately considered illegal. Not to bother you with trivia, but lately a psychiatrist in sunny California, no less, was put in jail for not telling the police what he knew about a patient."

"That a threat?"

"Don't talk paranoid. I mention it in passing."

"I could always tell the judge it was a matter of confession," said the Jesuit, grinning wryly as he stood to tuck his shirt in. "Plainly speaking," he added.

The detective glanced up at him, faintly gloomy. "Want to go into business, Father?" he said Then looked away dismally. " 'Father'... what 'Father'?" he asked rhetorically. "You're a Jew; I could tell when I met you."

The Jesuit chuckled.

"Yes, laugh," said Kinderman. "Laugh." But then he smiled, looking impishly pleased with himself. He turned with beaming eyes. "That reminds me. The entrance examination to be a policeman, Father? When I took it, one question went something like: 'What are rabies and what would you do for them?' Know what some dumbhead put down for an answer? Emis? 'Rabies,' he said, 'are Jew priests, and I would do anything that I could for them.' Honest!" He'd raised up a hand as in oath.

Karras laughed. "Come on, I'll walk you to your car. Are you parked in the lot?"

The detective looked up at him, reluctant to move. "Then we're finished?"

The priest put a foot on the bench, leaning over, an arm resting heavily on his knee. "Look, I'm really not covering up," he said. "Really. If I knew of a priest like the one you're looking for, the least I would do is to tell you that there was such a man without giving you his name. Then I guess I'd report it to the Provincial. But I don't know of anyone who even comes close."

"Ah, well," the detective sighed. "I never thought it was a priest in the first place. Not really." He nodded toward the parking lot. "Yes, I'm over there."

They started walking.

"What I really suspect," the detective continued, "if I said it out loud you would call me a nut. I don't know. I don't know." He was shaking his head. "All these clubs and these cults where they kill for no reason. It makes you start thinking peculiar things. To keep up with the times, these days, you have to be a little bit crazy."

Karras nodded.

"What's that thing on your shirt?" the detective asked him, motioning his head toward the Jesuit's chest.

"What thing?"

"On the T-shirt," the detective clarified. "The writing. 'Philosophers.' "

"Oh, I taught a few courses one year," said Karras, "at Woodstock Seminary in Maryland. I played on the lower-class baseball team. They were called the Philosophers.'

"Ah, and the upper-class team?"

"Theologians."

Kinderman smiled and shook his head. "Theologians three, Philosophers two," he mused.

"Philosophers three, Theologians two."