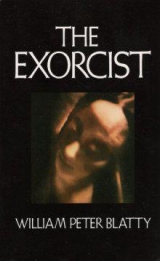

Текст книги "The Exorcist"

Автор книги: William Peter Blatty

Жанр:

Мистика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

He waited for the laughter to ebb before hd spoke: "Quam profundus est imus Oceanus Indicus?" What is the depth of the Indian Ocean at its deepest point?

The demon's eyes glittered: "La plume de ma tante," it rasped.

"Responde Latine."

"Bon jour! Bonne nuit!"

"Quam–"

Karras broke off as the eyes rolled upward into their sockets and the gibberish entity appeared.

Impatient and frustrated, Karras demanded, "Let me speak to the demon again!"

No answer. Only the breathing from another shore.

"Quis es tu?'" he snapped hoarsely. Voice frayed.

Still the breathing.

"Let me speak to Burke Dennings!"

A hiccup. Breathing. A hiccup. Breathing.

"Let me speak to Burke Dennings!"

The hiccupping, regular and wrenching, continued. Karras shook his head. Then he walked to a chair and sat on its edge. Hunched over. Tense. Tormented. And waiting...

Time passed. Karras drowsed. Then jerked his head up. Stay awake! With blinking, heavy lids, he looked over at Regan. No hiccupping. Silent.

Sleeping?

He walked over to the bed and looked down. Eyes closed. Heavy breathing. He reached down and felt her pulse, then stooped and carefully examined her lips. They were parched. He straightened up and waited. Then at last he left the room.

He went down to the kitchen in search of Sharon; and found her at the table eating soup and a sandwich. "Can I fix you something to eat, Father Karras?" she asked him. "You must be hungry."

"

"Thanks, no, I'm not," he answered. Sitting down, he reached over and picked up a pencil and pad by Sharon's typewriter. "She's been hiccupping," he told her. "Have you had any Compazine prescribed?"

"Yes, we've got some."

He was writing on the pad. "Then tonight give her half of a twenty-five-milligram suppository."

"Right."

"She's beginning to dehydrate," he continued, "so I'm switching her to intravenous feedings. First thing in the morning, call a medical-supply house and have them deliver these right away." He slid the pad across the table to Sharon. "In the Meantime, she's sleeping, so you could start her on a Sustagen feeding."

"Okay." Sharon nodded. "I will." Spooning soup, she turned the pad around and looked at the list."

Karras watched her. Then he frowned in concentration.

"You're her tutor."

"Yes, that's right."

"Have you taught her any Latin?"

She was puzzled. "No, I haven't.-"

"Any German?"

"Only French."

"What level? La plume de ma tante?"

"Pretty much."

"But no German or Latin."

"Huh-nh, no."

"But the Engstroms, don't they sometimes speak German?"

"Oh, sure."

"Around Regan?"

She shrugged. "I suppose." She stood up and took her plates to the sink. "As a matter of fact, I'm pretty sure."

"Have you ever studied Latin?" Karras asked her.

"No, I haven't."

"But you'd recognize the general sound."

"Oh, I'm sure." She rinsed the soup bowl and put it in the rack.

"Has she ever spoken Latin in your presence?"

"Regan?"

"Since her illness."

"No, never."

"Any language at all?" probed Karras.

She tuned off the faucet, thoughtful. "Well, I might have imagined it, I guess, but..."

"What?"

"Well, I think..." She frowned. "Well, I could have sworn I heard her talking in Russian."

Karras stared. "Do you speak it?" he asked her, throat dry.

She shrugged. "Oh, well, so-so." She began to fold the dishcloth: "I just studied it in college, that's all. "

Karras sagged. She did pick the Latin from my brain. Staring bleakly; he lowered his brow to his hand, into doubt, into torments of knowledge and reason: Telepathy more common in states of great tension: speaking always in a language known to someone in the room: "... thinks the same things I'm thinking...": "Bon jour...": "La plume de ma tante...": "Bonne nuit..." With thoughts such as these, he slowly watched blood turning back into wine.

What to do? Get some sleep. Then come back es»d try again... try again... try again.

He stood up and looked blearily at Sharon. She was leaning with her back against the sink, arms folded, watching him thoughtfully. "I'm going over to the residence," he told her. "As soon as Regan's awake, I'd like a call."

"Yes, I'll call you."

"And the Compazine," he reminded her. "You won't forget?"

She shook her head. "No, I'll take care of it right away," she said.

He nodded. With hands in hip pockets, he looked down, trying to think of what he might have forgotten to tell Sharon. Always something to be done. Always something overlooked when even everything was done.

"Father, what's going on?" he heard her ask gravely. "What is it? What's really going on with Rags?"

He lifted up eyes that were haunted and seared. "I really don't know," he said emptily.

He turned and walked out of the kitchen.

As he passed through the entry hall, Karras heard footsteps coming up rapidly behind him.

"Father Karras!"

He turned. Saw Karl with his sweater.

"Very sorry," said the servant as he handed it over. "I was thinking to finish much before. But I forget."

The vomit stains were gone and it had a sweet smell. "That was thoughtful of you, Karl," the priest said gently. "Thank you."

"Thank you, Father Karras."

There was a tremor in his voice and his eyes were full.

"Thank you for your helping Miss Regan," Karl finished. Then he averted his head, self-conscious, and swiftly left the entry.

Karras watched, remembering him in Kinderman's car. More mystery. Confusion. Wearily he opened the door. It was night. Despairing, he stepped out of darkness into darkness.

He crossed to the residence, groping toward sleep, but as he entered his room he looked down and saw a message slip pink on the floor. He picked it up. From Frank. The tapes. Home number. "Please call...."

He picked up the telephone and requested the number. Waited. His hands shook with desperate hope.

"Hello?" A young boy. Piping voice.

"May I speak to your father, please."

"Yes. just a minute." Phone clattering. Then quickly picked up. Still the boy. "Who is this?"

"Father Karras."

"Father Karits?"

His heart thumping, Karras spoke evenly, "Karras. Father Karras..."

Down went the phone again.

Karras pressed digging fingers against his brow.

Phone noise.

"Father Karras?"

'Yes, hello, Frank. I've been trying to reach you."

"Oh, I'm sorry. I've been working on your tapes at the house."

"Are you finished?"

"Yes, I am. By the way, this is pretty weird stuff."

"I know." Karras tried to flatten the tension in his voice. "What's the story, Frank? What have you found?"

"Well, this 'type-token' ratio, first..."

"Yes?"

"Well, I didn't have enough of a sampling to be absolutely accurate, you understand, but I'd say it's pretty close, or at least as close as you can get with these things. Well, at any rate, the two different voices on the tapes, I would say, are probably separate personalities."

"Probably?"

"Well, I wouldn't want to swear to it in court. In fact, I'd have to say the variance is really pretty minimal."

"Minimal..." Karras repeated dully. Well, that's the ball game. "And what about the gibberish?" he asked without hope. "Is it any kind of language?"

Frank chuckled.

"What's funny?" asked the Jesuit moodily.

"Was this really some sneaky psychological testing, Father?"

"I don't know what you mean, Frank."

"Well, I guess you got your tapes mixed around or something. It's–"

"Frank, is it a language or not?" cut in Karras.

"Oh, I'd say it was a language, all right."

Karras stiffened. "Are you kidding?"

'No, I'm not."

"What's the language?" he asked, unbelieving.

"English."

For a moment, Karras was mute, and when he spoke there was an edge to his voice. "Frank, we seem to have a very poor connection; or would you like to let me in on the joke?"

"Got your tape recorder there?" asked Frank.

It was sitting on his desk. "Yes, I do."

"Has it got a reverse-play position?"

"Why?"

"Has it got one?"

"Just a second." Irritable, Karras set down the phone and took the top off the tape recorder to check it. "Yes, it's got one. Frank, what's this all about?"

"Put your tape on the machine and play it backward."

"What?"

"You've got gremlins." Frank laughed, "Look, play it and I'll talk to you tomorrow. Good night, Father."

"Night, Frank."

"Have fun."

Karras hung up. He looked baffled. He hunted up the gibberish tape and threaded it onto the recorder. First he ran it forward, listening. Shook his head. No mistake. It was gibberish.

He let it run through to the end and then played it in reverse. He heard his voice speaking backward. Then Regan–or someone–in English!

... Marin marin karras be us let us...

English. Senseless; but English! How on earth could she do that? he marveled.

He listened to it all, then rewound and played the tape through again. And again. And then realized that the order of speech was inverted.

He stopped the tape and rewound it. With a pencil and paper, he sat down at the desk and began to play the tape from the beginning while transcribing the words, working laboriously and long with almost constant stops and starts of the tape recorder. When finally it was done, he made another transcription on a second sheet of paper, reversing the order of the words. Then he leaned back and read it: ... danger. Not yet. [indecipherable] will die. Little time. Now the [indecipherable]. Let her die. No, no, sweet! it is sweet in the body! I feel! There is [indecipherable]. Better [indecipherable] than the void. I fear the priest. Give us time. Fear the priest! He is [indecipherable]. No, not this one: the [indecipherable], the one who [indecipherable]. He is ill. Ah, the blood, feel the blood, how it [sings?].

Here, Karras asked, "Who are you?" with the answer: I am no me. I am no one.

Then Karras: "Is that your name?" and then: I have no name. I am no one. Many. Let us be. Let us warm in the body. Do not [indecipherable] from the body into void, into [indecipherable]. Leave us. Leave us. Let us be. Karras. [Marin?

Marin?]...

Again and again he read it over, haunted by its tone, by the feeling that more than one person was speaking, until finally repetition itself dulled the words into commonness. He set down the tablet on which he'd transcribed them and rubbed at his face, at his eyes, at his thoughts. Not an unknown language. And writing backward with facility was hardly paranormal or even unusual. But speaking backward: adjusting and altering the phonetics so that playing them backward would make them intelligible;. wasn't such performance beyond the reach of even a hyperstimulated intellect? The accelerated unconscious referred to by Jung? No. Something...

He remembered. He went to his shelves for a book: Jung's Psychology and Pathology of So-called Occult Phenomena. Something similar here, he thought. What?

He found it: an account of an experiment with automatic writing in which the unconscious of the subject seemed able to answer his questions and anagrams.

Anagrams!

He propped the book open on the desk, leaned over and read an account of a portion of the experiment: 3rd DAY What is man? Tefi hasl esble lies.

Is that an anagram? Yes.

How many words does it contain? Five.

What is the first word? See.

What is the second word? Eeeee.

See? Shall I interpret it myself? Try to!

The subject found this solution: "The life is less able." He was astonished at this intellectual pronouncement, which seemed to him to prove the existence of an intelligence independent of his own. He therefore went on to ask: Who are you? Clelia.

Are you a woman? Yes.

Have you lived on earth? No.

Will you come to life? Yes.

When? In six years.

Why are you conversing with me? E if Cledia el.

The subject interpreted this answer as an anagram for "I Clelia feel."

4TH DAY

Am I the one who answers the questions? Yes.

Is Clelia there? No.

Who is there, then? Nobody.

Does Clelia exist at all? No.

Then with whom was I speaking yesterday? With nobody.

Karras stopped reading. Shook his head. Here was no paranormal performance: only the limitless abilities of the mind.

He reached for a cigarette, sat down and lit it. "I am no one. Many." Eerie. Where did it come from, he wondered, this content of her speech?

"With nobody."

From the same place Clelia had come from? Emergent personalities?

"Marin... Marin..."

"Ah, the blood..."

"He is ill...."

Haunted, he glanced at his copy of Satan and moodily leafed to the opening inscription: "Let not the dragon be my leader...."

He exhaled smoke and closed his eyes. He coughed. His throat felt raw and inflamed. He crushed out the cigarette, eyes watering from smoke. exhausted. His bones felt like iron pipe. He got up and put out a "Do Not Disturb" sign on the door, then he flicked out the room light, shuttered his window blinds, kicked off his shoes and collapsed on the bed. Fragments. Regan. Dennings. Kinderman. What to do? He must help. How?

Try the Bishop with what little he had? He did not think so. He could never convincingly argue the case.

He thought of undressing, getting under the covers. Too tired. This burden. He wanted to be free.

"... Let us be!"

Let me be, he responded to the fragment. He drifted into motionless, dark granite sleep.

The ringing of a telephone awakened him. Groggy, he fumbled toward the light switch. What time was it? A few minutes after three. He reached blindly for the telephone. Answered. Sharon. Would he come to the house right away? He would come. He hung up the telephone, feeling trapped again, smothered and enmeshed.

He went into the bathroom and splashed cold water on his face, dried off and then started from the room, but at the door, he turned around and came back for his sweater. He pulled it over his head and then went out into the street.

The air was thin and still in the darkness. Some cats at a garbage can scurried in fright as he crossed toward the house.

Sharon met him at the door. She was wearing a sweater and was draped in a blanket. She looked frightened. Bewildered. "Sorry, Father," she whispered as he entered the house, "but I thought you ought to see this."

"What?"

"You'll see. Let's be quiet, now. I don't want to wake up Chris. She shouldn't see this." She beckoned.

He followed her, tiptoeing quietly up the stairs to Regan's bedroom. Entering, the Jesuit felt chilled to the bone. The room was icy. He frowned in bewilderment at Sharon, and she nodded at him solemnly. "Yes. Yes, the heat's on," she whispered. Then she turned and stared at Regan, at the whites of her eyes glowing eerily in lamplight. She seemed to be in coma. Heavy breathing. Motionless. The nasogastric tube was in place, the Sustagen seeping slowly into her body.

Sharon moved quietly toward the bedside and Karras followed, still staggered by the cold. When they stood by the bed, he saw beads of perspiration on Regan's forehead; glanced down and saw her hands gripped firmly in the restraining straps.

Sharon. She was bending, gently pulling the top of Regan's pajamas wide apart, and an overwhelming pity hit Karras at the sight of the wasted chest, the protruding ribs where one might count the remaining weeks or days of her life.

He felt Sharon's haunted eyes upon him. "I don't know if it's stopped," she whispered. "But watch: just keep looking at her chest."

She turned and looked down, and the Jesuit, puzzled, followed her gaze. Silence. The breathing. Watching. The cold. Then the Jesuit's brows knitted tightly as he saw something happening to the skin: a faint redness, but in sharp definition; like handwriting. He peered down closer.

"There, it's coming," whispered Sharon.

Abruptly the gooseflesh on Karras' arms was not from the icy cold in the room; was from what he was seeing on Regan's chest; was from bas-relief script rising up in clear letters of blood-red skin. Two words: help me "That's her handwriting," whispered Sharon.

At 9: 00 that morning, Damien Karras came to the president of Georgetown University and asks for permission to seek an exorcism. He received it, and immediately afterward went to the Bishop of the diocese, who listened with grave attention to all that Karras had to say.

"You're convinced that it's genuine?" the Bishop asked finally.

"I've made a prudent judgment that it meets the conditions set forth in the Ritual," answered Karras evasively. He still did not dare believe. Not his mind but his heart had tugged him to this moment; pity and the hope for a cure through suggestion.

"You would want to do the exorcism yourself?" asked the Bishop.

He felt a moment of elation; saw the door swinging open to fields, to escape from the crushing weight of caring and that meeting each twilight with the ghost of his faith. "Yes, of course," answered Karras.

"How's your health?"

"All right."

"Have you ever been involved with this sort of thing before?"

"No, I haven't."

"Well, we'll see. It might be best to have a man with experience. There aren't too many, of course, but perhaps someone back from the foreign missions. Let me see who's around. In the meantime, I'll call you as soon as we know."

When Karras had left him, the Bishop called the president of Georgetown University, and they talked about him for the second time that day.

"Well, he does know the background," said the president at a point in their conversation. "I doubt there's any danger in just having him assist. There should be a psychiatrist present, anyway."

"And what about the exorcist? Any ideas? I'm blank."

"Well, now, Lankester Merrin's around."

"Merrin? I had a notion he was over is Iraq. I think I read he was working on a dig around Nineveh."

"Yes, down below Mosul. That's right. But he finished and came back around three or four months ago, Mike.

He's at Woodstock."

"Teaching?"

"No, working on another book."

"God help us! Don't you think he's too old, though? "How's his health?"

"Well, it must be all right or he wouldn't still be running around digging up tombs, don't you think?"

"Yes, I suppose so."

"And besides, he's had experience, Mike."

"I didn't know that."

"Well, at least that's the word."

"When was that?"

"Oh, maybe ten or twelve years ago, I think, in Africa. Supposedly the exorcism lasted for months. I heard it damn near killed him."

"Well, in that case, I doubt that he'd want to do another one."

"We do what we're told here, Mike. All the rebels are over with you seculars."

"Thanks for reminding me."

"Well, what do you think?"

"Look, I'll leave it up to you and the Provincial."

Early that silently waiting evening, a young scholastic preparing for the priesthood wandered the grounds of Woodstock Seminary in Maryland. He was searching for a slender, gray-haired old Jesuit. He found him on a pathway, strolling through a grove. He handed him a telegram. The old man thanked him, serene, eyes kindly, then turned and renewed his contemplation; continued his walk through a nature that he loved. Now and then he would pause to hear the song of a robin, to watch a bright butterfly hover on a branch. He did not open and read the telegram. He knew what it said. He had known. He had read it in the dust of the temples of Nineveh. He was ready.

He continued his farewells.

IV: "And let my cry come unto Thee..."

"He who abides in love, abides in God, and God in him..." –Saint Paul.

CHAPTER ONE

In the breathing dark of his quiet office, Kinderman brooded above his desk.

He adjusted the desk-lamp beams a fraction. Below him were records, transcripts, exhibits; police files; crime-lab reports; scribbled notes. In a pensive mood, he had carefully fashioned them into a collage in the shape of a rose, as if to belie the ugly conclusion to which they had led him; that he could not accept.

Engstrom was innocent. At the time of Dennings' death, he had been visiting his daughter, supplying her with money for the purchase of drugs. He had lied about his whereabouts that night in order to protect her and to shield her mother, who believed Elvira to be dead and past all harm and degradation.

It was not from Karl that Kinderman had learned this. On the night of their encounter in Elvira's hallway, the servant remained obdurately silent. It was only when Kinderman apprised the daughter of her father's involvement in the Dennings case that Elvira volunteered the truth. There were witnesses to confirm it. Engstrom was innocent. Innocent and silent concerning events in Chris MacNeil's house.

Kinderman frowned at the rose collage. Something was wrong with the composition. He shifted a petal point–the corner of a deposition–a trifle lower and to the right.

Roses. Elvira. He had warned her grimly that failure to check herself into a clinic within two weeks would result in his dogging her trail with warrants until he had evidence to effect her arrest. Yet he did not really believe she would go. There were times when he stared at the law unblinkingly as he would the noonday sun in the hope it would temporarily blind him while some quarry made its escape.

Engstrom was innocent. What remained?

Kinderman, wheezing, shifted his weight. Then he closed his eyes and imagined he was soaking in a lapping hot bath. Mental Closeout Sale! he bannered at himself: Moving to New Conclusions! Positively Everything Must Go! For a moment he waited, unconvinced. Then, Positively! he added sternly.

He opened his eyes and examined afresh the bewildering data.

Item: The death of director Burke Dennings seemed somehow linked to the desecrations at Holy Trinity. Both involved witchcraft and the unknown desecrator could easily be Dennings' murderer.

Item: An expert on witchcraft, a Jesuit priest, had been seen making visits to the home of the MacNeils.

Item: The typewritten sheet of paper containing the text of the blasphemous altar card discovered at Holy Trinity had been checked for latent fingerprints. Impressions had been found on both sides. Some had been made by Damien Karras. But still another set had been found that, from their size, were adjudged to be those of a person with very small hands, quite possibly a child.

Item: The typing on the altar card had been analyzed and compared with the typed impressions on the unfinished letter that Sharon Spencer had pulled from her typewriter, crumpled up, and tossed at a wastepaper basket, missing it, while Kinderman had been questioning Chris. He had picked it up and smuggled it out of the house. The typing on this letter and the typing on the altar-card sheet had been done on the same machine. According to the reports however, the touch of the typists differed. The person who had typed the blasphemous text had a touch far heavier than Sharon Spencer's. Since the typing of the former, moreover, had not been "hunt and peck" but, rather, skillfully accomplished, it suggested that the unknown typist of the altar-card text was a person of extraordinary strength.

Item: Burke Dennings–if his death was not an accident–had been killed by a person of extraordinary strength.

Item: Engstrom was no longer a suspect.

Item: A check of domestic airline reservations disclosed that Chris MacNeil had taken her daughter to Dayton, Ohio. Kinderman had known that the daughter was ill and was being taken to a clinic. But the clinic in Dayton would have to be Barringer. Kinderman had checked and the clinic confirmed that the daughter had been in for observation. Though the clinic refused to state the nature of the illness, it was obviously a serious mental disorder.

Item: Serious mental disorders at times caused extraordinary strength.

Kinderman sighed and closed his eyes. The same. He was back to the same conclusion. He shook his head. Then he opened his eyes and stared at the center of the paper rose: a faded old copy of a national news magazine. On the cover were Chris and Regan. He studied the daughter: the sweet, freckled face and the ribboned ponytails, the missing front tooth in the grin. He looked out a window into darkness. A drizzling rain had begun to fall.

He went down to the garage, got into the unmarked black sedan and then drove through rain-slick, shining streets to the Georgetown area, where he parked on the eastern side of Prospect Street. And sat. For a quarter of an hour. Sat. Staring at Regan's window. Should he knock at the door and demand to see her? He lowered his head. Rubbed at his brow. William F. Kinderman, you are sick! You are ill! Go home! Take medicine! Sleep!

He looked up at the window again and ruefully shook his head. Here his haunted logic had led him.

He shifted his gaze as a cab pulled up to the house. He started the engine and turned on the windshield wipers.

From the cab stepped a tall old man. Black raincoat and hat and a battered valise. He paid the driver, then turned and stood motionless, staring at the house. The cab pulled away and rounded the corner of Thirty-sixth Street. Kinderman quickly pulled out to follow. As he turned the corner, he noticed that the tall old man hadn't moved, but was standing under street-light glow, in mist, like a melancholy traveler frozen in time. The detective blinked his lights at the taxi.

Inside, at that moment, Karras and Karl pinned Regan's arms while Sharon injected her with Librium, bringing the total amount injected in the last two hours to four hundred milligrams. The dosage, Karras knew, was staggering. But after a lull of many hours, the demonic personality had suddenly awaked in a fit of fury so frenzied that Regan's debilitated system could not for very long endure it.

Karras was exhausted. After his visit to the Chancery Office that morning, he returned to the house to tell Chris what had happened Then he set up an intravenous feeding for Regan, went back to his room and fell on his bed. After only an hour and a half of sleep, however, the telephone had wrenched him awake. Sharon. Regan was still unconscious and her pulse had been gradually slipping lower. Karras had then rushed to the house with his medical bag and pinched Regan's Achilles tendon, looking for reaction to pain. There was none. He pressed down hard on one of her fingernails. Again no reaction. He was worried. Though he knew that in hysteria and in states of trance there was sometimes an insensitivity to pain, he now feared coma, a state from which Regan might slip easily into death. He checked her blood pressure: ninety over sixty; then pulse rate: sixty. He had waited in the room then, and checked her again every fifteen minutes for an hour and a half before he was satisfied that blood pressure and pulse rate had stabilized, meaning Regan was not in shock but in a state of stupor. Sharon was instructed to continue to check the pulse each hour. Then he'd returned to his room and his sleep. But again the telephone woke him up. The exorcist, the Chancery Office told him, would be Lankester Merrin. Karras would assist.

The news had stunned him. Merrin! the philosopher-paleontologist! the soaring, staggering intellect! His books had stirred ferment in the Church; for they interpreted his faith in the terms of science, in terms of a matter that was still evolving, destined to be spirit and joined to God.

Karras telephoned Chris at once to convey the news, but found that she'd heard from the Bishop directly. He had told her that Merrin would arrive the next day. "I told the Bishop he could stay at the house," Chris said. "It'll just be a day or so, won't it?" Before answering, Karras paused. "I don't know." And then, pausing again, said, "You mustn't expect too much."

"If it works, I mean," Chris had answered. Her tone had been subdued. "I didn't mean to imply that it wouldn't," he reassured her. "I just meant that it might take time."

"How long?"

"It varies." He knew that an exorcism often took weeks, even months; knew that frequently it failed altogether. He expected the latter; expected that the burden, barring cure through suggestion, would fall once again, and at the last, upon him. "It can take a few days or weeks," he'd then told her. "How long has she got, Father Karras?..."

When he hung up the phone, he'd felt heavy, tormented. Stretched out on the bed, he thought of Merrin. Merrin! An excitement and a hope seeped through him. A sinking disquiet followed. He himself had been the natural choice for exorcist, yet the Bishop had passed him over. Why? Because Merrin had done this before?

As he closed his eyes, he recalled that exorcists were selected on the basis of "piety" and "high moral qualities"; that a passage in the gospel of Matthew related that Christ, when asked by his disciples the cause of their failure in an effort at exorcism, had answered them: "... because of your little faith."

The Provincial had known about his problem; so had the president, Karras reflected. Had either told the Bishop?

He had turned on his bed then, damply despondent; felt somehow unworthy; incompetent; rejected. It stung. Unreasonably, it stung. Then, finally, sleep came pouring into emptiness, filling in the niches and cracks in his heart.

But again the ring of the phone woke him, Chris calling to inform him of Regan's new frenzy. Back at the house, he checked Regan's pulse. It was strong. He gave Librium, then again. And again. Finally, he made his way to the kitchen, briefly joining Chris at the table for coffee. She was reading a book, one of Merrin's that she'd ordered delivered to the house. "Way over my head," she told him softly, yet she looked touched and deeply moved. "But there's some of it so beautiful–so great." She flipped back through pages to a passage she had marked, and handed the book across the table to Karras. He read: ... We have familiar experience of the order, the constancy, the perpetual renovation of the material world which surrounds us. Frail and transitory as is every part of it, restless and migratory as are its elements, still it abides. It is bound together by a law of permanence, and though it is ever dying, it is ever coming to life again. Dissolution does but give birth to fresh modes of organization, and one death is the parent of a thousand lives. Each hour, as it comes, is but a testimony how fleeting, yet how secure; how certain, is the great whole. It is like an image on the waters, which is ever the same, though the waters ever flow. The sun sinks to rise again; the day is swallowed up in the gloom of night, to be born out of it, as fresh as if it had never been quenched. Spring passes into summer, and through summer and autumn into winter, only the more surely, by its own ultimate return, to triumph over that grave towards which it resolutely hastened from its first hour. We mourn the blossoms of May because they are to wither; but we know that May is one day to have its revenge upon November, by the revolution of that solemn circle which never stops–which teaches us in our height of hope, ever to be sober, and in our depth of desolation, never to despair.