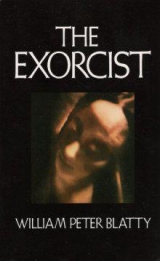

Текст книги "The Exorcist"

Автор книги: William Peter Blatty

Жанр:

Мистика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

Annotation

Originally published in 1971, The Exorcist, one of the most controversial novels ever written, went on to become a literary phenomenon: It spent fifty-seven weeks on the New York Times bestseller list, seventeen consecutively at number one. Inspired by a true story of a child’s demonic possession in the 1940s, William Peter Blatty created an iconic novel that focuses on Regan, the eleven-year-old daughter of a movie actress residing in Washington, D.C. A small group of overwhelmed yet determined individuals must rescue Regan from her unspeakable fate, and the drama that ensues is gripping and unfailingly terrifying. Two years after its publication, The Exorcist was, of course, turned into a wildly popular motion picture, garnering ten Academy Award nominations. On opening day of the film, lines of the novel’s fans stretched around city blocks. In Chicago, frustrated moviegoers used a battering ram to gain entry through the double side doors of a theater. In Kansas City, police used tear gas to disperse an impatient crowd who tried to force their way into a cinema. The three major television networks carried footage of these events; CBS’s Walter Cronkite devoted almost ten minutes to the story. The Exorcist was, and is, more than just a novel and a film: it is a true landmark. Purposefully raw and profane, The Exorcist still has the extraordinary ability to disturb readers and cause them to forget that it is “just a story.” Published here in this beautiful fortieth anniversary edition, it remains an unforgettable reading experience and will continue to shock and frighten a new generation of readers.

Спасибо, что скачали книгу в бесплатной электронной библиотеке Royallib.ru

Все книги автора

Эта же книга в других форматах

Приятного чтения!

THE EXORCIST

William Peter Blatty

To my brothers and sisters, Maurice, Edward and Alyce, and in loving memory of my parents.

'Now when [Jesus] stepped ashore, there met him a certain man who for a long time was possessed by a devil.... Many times it had laid hold of him and he was bound with chains.... but he would break the bonds asunder.... And Jesus asked him, saying, "What is thy name?" And he said Legion....'

–Luke 8: 27-30

James Torello: Jackson was hung up on that meat hook. He was so heavy he bent it. He was on that thing three days before he croaked.

Frank Buccieri (giggling): Jackie, you shoulda seen the guy. Like an elephant, he was, and when Jimmy hit him with that electric prod...

Torello (excitedly): He was floppin' around on that hook, Jackie.

We tossed water on him to give the prod a better charge, and he's screamin'....

–Excerpt from FBI wiretap of Cosa Nostra telephone conversation relating to murder of William Jackson ...

There's no other explanation for some of the things the Communists did. Like the priest who had eight nails driven into his skull.... And there were seven little boys and their teacher. They were praying the Our Father when soldiers came upon them. One soldier whipped out his bayonet and sliced off the teacher's tongue. The other took chopsticks and drove them into the ears of the seven little boys. How do you treat cases like that?

Dr. Tom Dooley

Dachau, Auschwitz, Buchenwald

AUTHOR'S NOTE I Have taken a few liberties with the current geography of Georgetown University, notably with respect to the present location of the Institute of Languages and Linguistics. Moreover, the house on Prospects Street does not exist, nor does the reception room of the Jesuit residence halls as I have described it.

The fragment of prose attributed to Lankester Merrin is not my creation, but is taken from a sermon of John Henry Newman entitled 'The Second Spring'.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My special thanks to Herbert Tanney, M. D.; Mr. Joseph E. Jeffs, Librarian, Georgetown University; Mr. William Bloom; and Mrs. Ann Harris, my editor at Harper & Row, for their invaluable assistance and generosity in the preparation of this work. I would also like to thank the Rev. Thomas V. Bermingham, S. J., Vice-Provincial for Formation of the New York Province of the Society of Jesus, for suggesting the subject matter of this novel; and Mr. Marc Jaffe of Bantam Books for his singular (and lonely) faith in its eventual worth. To these mentions I would like to add Dr. Bernard M. Wagner of Georgetown University, for teaching me to write, and the Jesuits, for teaching me to think.

PROLOGUE

Northern Iraq

The blaze of sun wrung pops of sweat from the old man's brow, yet he cupped his hands around the glass of hot sweet tea as if to warm them. He could not shake the premonition. It clang to his back like chill wet leaves.

The dig was over. The tell had been sifted, stratum by stratum, its entrails examined, tagged and shipped: the beds and pendants; glyptics; phalli; ground-stone mortars stained with ocher; burnished pots. Nothing exceptional. An Assyrian ivory toilet box. And man. The bones of man. The brittle remnants of cosmic torment that once made him wonder if matter was Lucifer upward-groping back to his God. And yet now he knew better. The fragrance of licorice plant and tamarisk tugged his gaze to poppied hills; to reeded plains; to the ragged, rock-strewn bolt of road that flung itself headlong into dread. Northwest was Mosul; east, Erbil; south was Baghdad and Kirkuk and the fiery furnace of Nebuchadnezzar. He shifted his legs underneath the table in front of the lonely roadside chaykhana and stared at the grass stains on his boots and khaki pants. He sipped at his tea. The dig was over. What was beginning? He dusted the thought like a clay-fresh find but he could not tag it.

Someone wheezed from within the chaykhana: the withered proprietor shuffling toward him, kicking up dust in Russian-made shoes that he wore like slippers, groaning backs pressed under his heels. The dark of his shadow slipped over the table.

"Kaman chay, chawaga?"

The man, in khaki shook his head, staring down at the laceless, crusted shoes caked thick with debris of the pain of living. The stuff of the cosmos, he softly reflected: matter; yet somehow finally spirit. Spirit and the shoes were to him but aspects of a stuff more fundamental, a stuff that was primal and totally other.

The shadow shifted. The Kurd stood waiting like an ancient debt. The old man in khaki looked up into eyes that were damply bleached as if the membrane of an eggshell had been pasted over the irises. Glaucoma. Once he could not have loved this man.

He slipped out his wallet and probed for a coin among its tattered, crumpled tenants: a few dinars; an Iraqi driver's license; a faded plastic calendar card that was twelve years out of date. It bore an inscription on the reverse: WHAT WE GIVE TO THE POOR IS WHAT WE TAKE WITH US WHEN WE DIE. The card had been printed by the Jesuit Missions. He paid for his tea and left a tip of fifty fils on a splintered table the color of sadness.

He walked to his jeep. The gentle, rippling click of key sliding into ignition was crisp in the silence. For a moment he waited, feeling at the stillness. Clustered on the summit of a towering mound, the fractured rooftops of Erbil hovered far in the distance, poised in the clouds like a rubbled, mud-stained benediction. The leaves clutched tighter at the flesh of his back.

Something was waiting.

"Allah ma'ak, chawaga."

Rotted teeth. The Kurd was grinning, waving farewell. The man in khaki groped for a warmth in his pit of his being and came up with a wave and a mustered smile. It dimmed as he looked away. He started the engine, turned in a narrow, eccentric U and headed toward Mosul. The Kurd stood watching, puzzled by a heart– dropping sense of loss as the jeep gathered speed. What was it that was gone? What was it he had felt in the stranger's presence? Something like safety, he remembered; a sense of protection and deep well-being. Now it dwindled in the distance with the fast-moving jeep. He felt strangely alone.

The painstaking inventory was finished by ten after six. The Mosul curator of antiquities, an Arab with sagging cheeks, was carefully penning a final entry into the ledger on his desk. For a moment he paused, looking up at his friend, as he dipped his penpoint into an inkpot. The man in khaki seemed lost in thought. He was standing by a table, hand in his pockets, staring down at some dry, tagged whisper of the past. The curator observed him, curious, unmoving; then returned to the entry, writing in a firm, very small neat script. Then at last he sighed, setting down the pen as he noted the time. The train to Baghdad left at eight. He blotted the page and offered tea.

The man in khaki shook his head, his eyes still fixed upon something on the table. The Arab watched him, vaguely troubled. What was in the air? There was something in the air. He stood up and moved closer; then felt a vague prickling at the base of his neck as his friend at last moved, reaching down for an amulet and cradling it pensively in his hand. It was a green stone head of the demon Pazuzu, personification of the southwest wind. Its dominion was sickness and disease. The head was pierced. The amulet's owner had worn it as a shield.

"Evil against evil," breathed the curator, languidly fanning himself with a French scientific periodical, an olive-oil thumbprint smudged on the cover.

His friend did not move; he did not comment.

"Is something wrong?"

No answer.

"Father?"

The man in khaki still appeared not to hear, absorbed in the amulet, the last of his finds. After a moment he set it down, then lifted a questioning look to the Arab. Had he said something?

"Nothing."

They murmured farewells.

At the door, the curator took the old man's hand with an extra firmness. "My heart has a wish, Father: that you would not go."

His friend answered softly in terms of tea; of times; of something to be done.

"No, no, no, I meant home."

The man in khaki fixed his gaze on a speck of boiled chick-pea nestled in a corner of the Arab's mouth; yet his eyes were distant. "Home," he repeated. The word had the sound of an ending: "The States," the Arab curator added, instantly wondering why he had.

The man in khaki looked into the dark of the other's concern. He had never found it difficult to love this man.

"Good-bye;" he whispered; then quickly turned and stepped into the gathering gloom of the streets and a journey home whose length seemed somehow undetermined.

"I will see you in a year!" the curator called after him from the doorway. But the man in khaki never looked back. The Arab watched his dwindling form as he crossed a narrow street at an angle, almost colliding with a swiftly moving droshky. Its cab bore a corpulent old Arab woman, her face a shadow behind the black lace veil draped loosely over her like a shroud. He guessed she was rushing to some appointment. He soon lost sight of his hurrying friend.

The man in khaki walked, compelled.. Shrugging loose of the city, he breached the outskirts, crossing the Tigris. Nearing the ruins, he slowed his pace, for– with every step the inchoate presentiment took firmer, more horrible form. Yet he had to know. He would have to prepare.

A wooden plank that bridged the Khosr, a muddy stream, creaked under his weight. And then he was there; he stood on the mound where once gleamed fifteen-gated Nineveh, feared nest of Assyrian hordes. Now the city lay sprawled in the bloody dust of its predestination. And yet he was here, the air was still thick with him, that Other who ravaged his dreams.

A Kurdish watchman, rounding a corner, unslung his rifle and began to run toward him, then abruptly stopped and grinned with a wave of recognition and proceeded on his rounds.

The man in khaki prowled the ruins. The Temple of Nabu. The Temple of Ishtar. He sifted vibrations. At the palace of Ashurbanipal he paused; then shifted a sidelong glance to a limestone statue hulking in situ: ragged wings; taloned feet; bulbous, jutting, stubby penis and a mouth stretched taut in a feral grin. The demon Pazuzu.

Abruptly he sagged.

He knew.

It was coming.

He stared at the dust. Quickening shadows.. He heard dim yappings of savage dog packs prowling the fringes of the city. The orb of the sun was beginning to fall below the rim of the world. He rolled his shirt sleeves down and buttoned them as a shivering breeze sprang up. Its source was southwest.

He hastened toward Mosul and his train, his heart encased in the icy conviction that soon he would face an ancient enemy.

I: The Beginning

CHAPTER ONE

Like the brief doomed flare of exploding suns that registers dimly on blind men's eyes, the beginning of the horror passed almost unnoticed; in the shriek of what followed, in fact, was forgotten and perhaps not connected to the horror at all. It was difficult to judge.

The house was a rental. Brooding. Tight. A bride colonial gripped by ivy in the Georgetown section of Washington, D. C. Across the street was a fringe of campus belonging to Georgetown University; to the rear, a sheer embankment plummeting steep to busy M Street and, beyond, the muddy Potomac. Early on the morning of April 1, the house was quiet. Chris MacNeil was propped in bed, going over her lines for the neat day's filming; Regan, her daughter, was sleeping down the hall; and asleep downstairs in a room off the pantry were the middle-aged housekeepers, Willie and Karl. At approximately 12: 25 A. M., Chris glanced from her script with a frown of puzzlement. She heard rapping sounds. They were odd. Muffed. Profound. Rhythmically clustered. Alien code tapped out by a dead man.

Funny.

She listened for a moment; then dismissed it; but as the rappings persisted she could not concentrate. She slapped down the script on the bed.

Jesus, that bugs me!

She got up to investigate.

She went out to the hallway and looked around. It seemed to be coming from Regan's bedroom.

What is she doing?

She padded down the hall and the rappings grew suddenly louder, much faster, and as she pushed on the door and stepped into the room, they abruptly ceased.

What the heck's going on?

Her pretty eleven-year-old was asleep, cuddled tight to a large stuffed round-eyed panda. Pookey. Faded from years of smothering; years of smacking, warm, wet kisses.

Chris moved softly to her bedside and leaned over for a whisper. "Rags? You awake?"

Regular breathing. Heavy. Deep.

Chris shifted her glance around the room. Dim light from the hall fell pale and splintered on Regan's paintings; on Regan's sculptures; on more stuffed animals.

Okay, Rags. Old mother's ass is draggin'. Say it. "April Fool!"

And yet Chris knew it wasn't like her. The child had a shy and very diffident nature. Then who was the trickster? A somnolent mind imposing order on the rattlings of heating pipes or plumbing? Once, in the mountains of Bhutan, she had stared for hours at a Buddhist monk who was squatting on the ground in meditation. Finally, she thought she had seen him levitate. Perhaps. Recounting the story to someone, she invariably added "perhaps." And perhaps her mind, that untiring raconteur of illusion, had embellished the rappings.

Bullshit! I heard it!

Abruptly, she flicked a quick glance to the ceiling. There! Faint scratchings.

Rats in the attic, for pete's sake! Rats!

She sighed. That's it. Big tails. Thump, thump. She felt oddly relieved. And then noticed the cold. The room. It was icy.

She padded to the window. Checked it. Closed. She touched the radiator. Hot.

Oh, really?

Puzzled, she moved to the bedside and, touched her hand to Regan's cheek. It was smooth as thought and lightly perspiring.

I must be sick!

She looked at her daughter, at the turned-up nose and freckled face, and on a quick, warm impulse leaned over the bed and kissed her cheek. "I sure do love you," she whispered, then returned to her room and her bed and her script.

For a while, Chris studied. The film was a musical comedy remake of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. . A subplot had been added dealing with campus insurrections. Chris was starring. She played a psychology teacher who sided with the rebels. And she hated it. It's dumb! This scene is absolutely dumb! Her mind, though untutored, never mistook slogans for truth, and like a curious bluejay she would peck relentlessly through verbiage to find the glistening, hidden fact. And so the rebel cause, to her, was "dumb." It didn't make sense. How come? she now wondered. Generation gap? That's a crock; I'm thirty-two. It's just plain dumb, that's all, it's...!

Cool it. One more week.

They'd completed the interiors in Hollywood. All that remained were a few exterior scenes on the campus of Georgetown University, starting tomorrow. It was Easter vacation and the students were away.

She was getting drowsy. Heavy lids. She turned to a page that was curiously ragged. Bemused, she smiled. Her English director. When especially tense, he would tear, with quivering, fluttering hands, a narrow strip from the edge of the handiest page and then chew it, inch by inch, until it was all in a ball in his mouth.

Dear Burke.

She yawned, then glanced fondly at the side of her script. The pages looked gnawed. She remembered the rats. The little bastards sure got rhythm. She made a mental note to have Karl set traps for them in the morning.

Fingers relaxing. Script slipping loose. She let it drop. Dumb. It's dumb. A fumbling hand groping out to the light switch. There. She sighed. For a time she was motionless, almost asleep; and then kicked off her covers with a lazy leg. Too freaking hot.

A mist of dew clung soft and gentle to the windowpanes.

Chris slept. And dreamed about death in the staggering particular, death as if death were still never yet heard of while something was ringing, she gasping, dissolving, slipping off into void, thinking over and over, I am not going to be, I will die, I won't be, and forever and ever, oh, Papa, don't let them, oh, don't let them do it, don't let me be nothing forever and melting, unraveling, ringing, the ringing– The phone!

She leaped up with her heart pounding, hand to the phone and no weight in her stomach; a core with no weight and her telephone ringing.

She answered. The assistant director.

"In makeup at six, honey."

"Right."

"How ya feelin'?"

"If I go to the bathroom and it doesn't burn, then I figure I'm ahead."

He chuckled. "I'll see yon.'

"Right. And thanks."

She hung up. And for moments sat motionless, thinking of the dream. A dream? More like thought in the half life of waking. That terrible clarity. Gleam of the skull. Non-being. Irreversible. She could not imagine it. God, it can't be!

She considered. And at last bowed her head. But it is.

She went to the bathroom, put on a robe, and padded quickly down to the kitchen, down to life in sputtering bacon.

"Ah, good morning, Mrs. MacNeil."

Gray, drooping Willie, squeezing oranges, blue sacs beneath her eyes. A trace of accent. Swiss, like Karl's. She wiped her hands on a paper towel and started moving toward the stove.

"I'll get it, Willie." Chris, ever sensitive, had seen her weary look, and as Willie now grunted and turned back to the sink, the actress poured coffee, then moved to the breakfast nook. Sat down. And warmly smiled as she looked at her plate. A blush-red rose. Regan. That angel. Many a morning, when Chris was working, Regan would quietly slip out of bed, come down to the kitchen and place a flower, then grope her way crusty-eyed back to her sleep. Chris shook her head; rueful; recalling: she had almost named her Goneril. Sure. Right on. Get ready for the worst. Chris chuckled at the memory. Sipped at her coffee. As her gaze caught the rose again, her expression turned briefly sad, large green eyes grieving in a waiflike face. She'd recalled another flower. A son. Jamie. He had died long ago at the age of three, when Chris was very young and an unknown chorus girl on Broadway. She had sworn she would not give herself ever again as she had to Jamie; as she had to his father, Howard MacNeil. She glanced quickly from the rose, and as her dream of death misted upward from the coffee, she quickly lit a cigarette. Willie brought juice and Chris remembered the rats.. "Where's Karl?" she asked the servant.

"I am here, madam!"

Catting in lithe through a door off the pantry. Commanding. Deferential. Dynamic. Crouching. A fragment of Kleenex pressed tight to his chin where he'd nicked himself shaving. "Yes?" Thickly muscled, he breathed by the table. Glittering eyes. Hawk nose. Bald head.

"Hey, Karl, we've got rats in the attic. Better get us some traps."

"Where are rats?"

"I just said that."

"But the attic is clean."

"Well, okay, we've got tidy rats!"

"No rats."

"Karl, I heard them last night," Chris said patiently, controlling.

"Maybe plumbing," Karl probed; "maybe boards."

"Maybe rats! Will you buy the damn traps and quit arguing?"

"Yes, madam!" Bustling away. "I go now!"

"No not now, Karl! The stores are all closed!"

'They are closed!" chided Willie.

"I will see."

He was gone.

Chris and Willie traded glances, and then Willie shook her head, turning back to the bacon. Chris sipped at her coffee. Strange. Strange man. Like Willie, hard-working; very loyal; discreet. And yet something -about him made her vaguely uneasy. What was it? His subtle air of arrogance? Defiance? No. Something else. Something hard to pin down. The couple had been with her for almost six years, and yet Karl was a mask–a talking, breathing, untranslated hieroglyph running her errands on stilted legs. Behind the mask, though, something moved; she could hear his mechanism ticking like a conscience. She stubbed out her cigarette; heard the front door creaking open, then shut.

"They are closed," muttered Willie.

Chris nibbled at bacon, then returned to her room, where she dressed in her costume sweater and skirt. She glanced in a mirror and solemnly stared at her short red hair, which looked perpetually tousled; at the burst of freckles on the small, scrubbed face; then crossed her eyes and grinned idiotically. Hi, little wonderful girl next door! Can I speak to your husband? Your lover? Your pimp? Oh, your pimp's in the poorhouse? Avon calling! She stuck out her tongue at herself. Then sagged. Ah, Christ, what a life! She picked up her wig box, slouched downstairs, and walked out to the piquant tree-lined street.

For a moment she paused outside the house and gulped at the morning. She looked to the right. Beside the house, a precipitous plunge of old stone steps fell away to M Street far below. A little beyond was the upper entry to the Car Barn, formerly used for the housing of streetcars: Mediterranean, tiled roof; rococo turrets; antique brick. She regarded it wistfully. Fun. Fun street. Dammit, why don't I stay? But the house? Start to live? From somewhere a bell began to toll. She glanced toward the sound. The tower clock on the Georgetown campus. The melancholy resonance echoed on the river; shivered; seeped through her tired heart. She walked toward her work; toward ghastly charade; toward the straw-stuffed, antic imitation of dust.

She entered the main front gates of the campus and her depression diminished; then grew even less as she looked at the row of trailer dressing rooms aligned along the driveway close to the southern perimeter wall; and by 8 A. M. and the day's first shot, she was almost herself: She started an argument over the script.

"Hey, Burke? Take a look at this damned thing, will ya?"

"Oh, you do have a script, I see! How nice!" Director Burke Dennings, taut and, elfin, left eye twitching yet gleaming with mischief, surgically shaved a narrow strip from a page of her script with quivering fingers "I believe I'll munch," he cackled.

They were standing on the esplanade that fronted the administration building and were knotted in the center of actors; lights; technicians; extras; grips. Here and there a few spectators dotted the lawn, mostly Jesuit faculty. Numbers of children. The cameraman, bored, picked up Daily Variety as Dennings put the paper in his mouth and giggled, his breath reeking faintly of the morning's first gin.

"Yes, I'm terribly glad you've been given a script."

A sly, frail man in his fifties, he spoke with a charmingly broad British accent so clipped and precise that it lofted even crudest obscenities to elegance, and when he drank, he seemed always on the verge of guffaw; seemed constantly struggling to retain his composure.

"Now then, tell me, my baby. What is it? What's wrong?"

The scene in question called for the dean of the mythical college in the script to address a gathering of students in an effort to squelch a threatened "sit-in." Chris would then run up the steps to the esplanade, tear the bullhorn away from the dean and then point to the main administration building and shout, "Let's tear it down!"

"It just doesn't make sense," said Chris.

"Well, it's perfectly plain," lied Dennings.

"Why the heck should they tear down the building, Burke? What for?"

"Are you sending me up?"

"No, I'm asking 'what for?' "

"Because it's there, loves!"

"In the script?"

"No, on the grounds!"

"Well, it doesn't make sense, Burke. She just wouldn't do that."

"She would."

"No, she wouldn't."

"Shall we summon the writer? I believe he's in Paris!"

"Hiding?"

"Fucking!"

He'd clipped it off with impeccable diction, fox eyes glinting in a face like dough as the word rose crisp to Gothic spires. Chris fell weak to his shoulders, laughing. "Oh, Burke, you're impossible, dammit!"

"Yes." He said it like Caesar modestly confirming reports of his triple rejection of the crown. "Now then, shall we get on with it?"

Chris didn't hear. She'd darted a furtive, embarrassed glance to a nearby Jesuit, checking to see if he'd heard the obscenity. Dark, rugged face. Like a boxer's. Chipped. In his forties. Something sad about the eyes; something pained; and yet warm and reassuring as they fastened on hers. He'd heard. He was smiling. He glanced at his watch and moved away.

"I say, shall we get on with it!"

She turned, disconnected. "Yeah, sure, Burke, let's do it."

"Thank heaven."

"No, wait!"

"Oh, good Christ!"

She complained about the tag of the scene.. She felt that the high point was reached with her line as opposed to her running through the door of the building immediately afterward.

"It adds nothing," said Chris. "It's dumb."

"Yes, it is, love, it is," agreed Burke sincerely. "However, the cutter insists that we do it," he continued, "so there we are. You see?"

"No, I don't."

"No, of course not. It's stupid. You see, since the following scene"–he giggled–"begins with Jed coming at us through a door, the cutter feels certain of a nomination if the scene preceding ends with you moving off through a door."

"That's dumb."

"Well, of course it is! It's vomit! It's simply cunting puking mad! Now then, why don't we shoot it and trust me to snip it from the final cut. It should make -a rather tasty munch."

Chris laughed. And agreed. Burke glanced toward the cutter, who was known to be a temperamental egotist given to time-wasting argumentation. He was busy with the cameraman. The director breathed a sigh of relief.

Waiting on the lawn at the base of the steps while the lights were warming, Chris looked toward Dennings as he flung an obscenity at a hapless grip and then visibly glowed. He seemed to revel in his eccentricity. Yet at a certain point in his drinking, Chris knew, he would suddenly explode into temper, and if it happened at three or four in the morning, he was likely to telephone people in power, and viciously abuse them over trifling provocations. Chris remembered a studio chief whose offense had consisted in remarking mildly at a screening that the cuffs of Dennings' shirt looked slightly frayed, prompting Dennings to awaken him at approximately 3 A. M. to describe him as a "cunting boor" whose father was "more that likely mad!" And on the following day, he would pretend to amnesia and subtly radiate with pleasure when those he'd offended described in detail what he had done. Although, if it suited him, he would remember. Chris thought with a smile of the night he'd destroyed his studio suite of offices in a gin-stoked, mindless rage, and how later, when confronted with an itemized bill and Polaroid photos detailing the damage, he'd archly dismissed them as "Obvious fakes, the damage was far, far worse than that!" Chris did not believe that Dennings was either an alcoholic or a hopeless problem drinker, but rather that he drank because it was expected of him: he was living up to his legend.

Ah, well, she thought; I guess it's a kind of immortality.

She turned, looking over her shoulder for the Jesuit who had smiled. He was walking in the distance, despondent, head lowered, a lone black cloud in search of the rain.

She had never liked priests. So assured. So secure. And yet this one...

"All ready, Chris?" Dennings.

"Yeah, ready."

"All right, absolute quiet!" The assistant director "Roll the film," ordered Burke.

"Speed."

"Now action!"

Chris ran up the steps while extras cheered and Dennings watched her, wondering what was on her mind. She'd given up the arguments far too quickly. He turned a significant look to the dialogue coach, who padded up to him dutifully and proffered his open script like an aging altar boy the missal to his priest at solemn Mass.

They worked with intermittent sun. By four, the overcast of roiling clouds was thick in the sky, and the assistant director dismissed the company for the day.