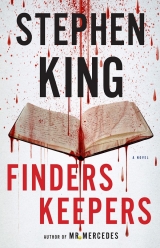

Текст книги "Finders Keepers"

Автор книги: Stephen Edwin King

Жанры:

Триллеры

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

A bolt of pain that had nothing to do with his hangover went through Morris’s head. ‘No! Not her! It can’t be! That bitch came over on the Ark!’

Cafferty smiled. ‘I deduce you’ve had doings with the Great Bukowski before.’

‘Check your file,’ Morris said dully. Although it probably wasn’t there. The Sugar Heights thing would be under seal, as he had told Andy.

Fucking Andy Halliday. This is more his fault than mine.

‘Homo.’

Cafferty frowned. ‘What did you say?’

‘Nothing. Go on.’

‘My file consists of last night’s arrest report. The good news is that your fate will be in some other judge’s hands when you come to trial. The better news, for me, at least, is that by that point, someone else will be representing you. My wife and I are moving to Denver and you, Mr Bellamy, will be just a memory.’

Denver or hell, it made no difference to Morris. ‘Tell me what I’m charged with.’

‘You don’t remember?’

‘I was in a blackout.’

‘Is that so.’

‘It actually is,’ Morris said.

Maybe he could trade the notebooks, although it hurt him to even consider it. But even if he made the offer – or if Cafferty made it – would a prosecutor grasp the importance of what was in them? It didn’t seem likely. Lawyers weren’t scholars. A prosecutor’s idea of great literature would probably be Erle Stanley Gardner. Even if the notebooks – all those beautiful Moleskines – did matter to the state’s legal rep, what would he, Morris, gain by turning them over? One life sentence instead of three? Whoopee-ding.

I can’t, no matter what. I won’t.

Andy Halliday might have been an English Leather-wearing homo, but he had been right about Morris’s motivation. Curtis and Freddy had been in it for cash; when Morris assured them the old guy might have squirreled away as much as a hundred thousand, they had believed him. Rothstein’s writings? To those two bumblefucks, the value of Rothstein’s output since 1960 was just a misty maybe, like a lost goldmine. It was Morris who cared about the writing. If things had gone differently, he would have offered to trade Curtis and Freddy his share of the money for the written words, and he was sure they would have taken him up on it. If he gave that up now – especially when the notebooks contained the continuation of the Jimmy Gold saga – it would all have been for nothing.

Cafferty rapped his phone on the Plexi, then put it back to his ear. ‘Cafferty to Bellamy, Cafferty to Bellamy, come in, Bellamy.’

‘Sorry. I was thinking.’

‘A little late for that, wouldn’t you say? Try to stick with me, if you please. You’ll be arraigned on three counts. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to plead not guilty to each in turn. Later, when you go to trial, you can change to guilty, should it prove to your advantage to do so. Don’t even think about bail, because Bukowski doesn’t laugh; she cackles like Witch Hazel.’

Morris thought, This is a case of worst fears realized. Rothstein, Dow, and Rogers. Three counts of Murder One.

‘Mr Bellamy? Our time is fleeting, and I’m losing patience.’

The phone sagged away from his ear and Morris brought it back with an effort. Nothing mattered now, and still the lawyer with the guileless Richie Cunningham face and the weird middle-aged baritone voice kept pouring words into his ear, and at some point they began to make sense.

‘They’ll work up the ladder, Mr Bellamy, from first to worst. Count one, resisting arrest. For arraignment purposes, you plead not guilty. Count two, aggravated assault – not just the woman, you also got one good one in on the first-responding cop before he cuffed you. You plead not guilty. Count three, aggravated rape. They may add attempted murder later, but right now it’s just rape … if rape can be called just anything, I suppose. You plead—’

‘Wait a minute,’ Morris said. He touched the scratches on his cheek, and what he felt was … hope. ‘I raped somebody?’

‘Indeed you did,’ Cafferty said, sounding pleased. Probably because his client finally seemed to be following him. ‘After Miss Cora Ann Hooper …’ He took a sheet of paper from his briefcase and consulted it. ‘This was shortly after she left the diner where she works as a waitress. She was heading for a bus stop on Lower Marlborough. Says you tackled her and pulled her into an alley next to Shooter’s Tavern, where you had spent several hours imbibing Jack Daniel’s before kicking the jukebox and being asked to leave. Miss Hooper had a battery-powered Police Alert in her purse and managed to trigger it. She also scratched your face. You broke her nose, held her down, choked her, and proceeded to insert your Johns Hopkins into her Sarah Lawrence. When Officer Philip Ellenton hauled you off, you were still matriculating.’

‘Rape. Why would I …’

Stupid question. Why had he spent three long hours tearing up that home in Sugar Heights, just taking a short break to piss on the Aubusson carpet?

‘I have no idea,’ Cafferty said. ‘Rape is foreign to my way of life.’

And mine, Morris thought. Ordinarily. But I was drinking Jack and got up to hijinks.

‘How long will they give me?’

‘The prosecution will ask for life. If you plead guilty at trial and throw yourself on the mercy of the court, you might only get twenty-five years.’

Morris pleaded guilty at trial. He said he regretted what he’d done. He blamed the booze. He threw himself on the mercy of the court.

And got life.

2013 – 2014

By the time he was a high school sophomore, Pete Saubers had already figured out the next step: a good college in New England where literature instead of cleanliness was next to godliness. He began investigating online and collecting brochures. Emerson or BC seemed the most likely candidates, but Brown might not be out of reach. His mother and father told him not to get his hopes up, but Pete didn’t buy that. He felt that if you didn’t have hopes and ambitions when you were a teenager, you’d be pretty much fucked later on.

About majoring in English there was no question. Some of this surety had to do with John Rothstein and the Jimmy Gold novels; so far as Pete knew, he was the only person in the world who had read the final two, and they had changed his life.

Howard Ricker, his sophomore English teacher, had also been life-changing, even though many kids made fun of him, calling him Ricky the Hippie because of the flower-power shirts and bellbottoms he favored. (Pete’s girlfriend, Gloria Moore, called him Pastor Ricky, because he had a habit of waving his hands above his head when he got excited.) Hardly anyone cut Mr Ricker’s classes, though. He was entertaining, he was enthusiastic, and – unlike many of the teachers – he seemed to genuinely like the kids, who he called ‘my young ladies and gentlemen.’ They rolled their eyes at his retro clothes and his screechy laugh … but the clothes had a certain funky cachet, and the screechy laugh was so amiably weird it made you want to laugh along.

On the first day of sophomore English, he blew in like a cool breeze, welcomed them, and then printed something on the board that Pete Saubers never forgot:

‘What do you make of this, ladies and gentlemen?’ he asked. ‘What on earth can it mean?’

The class was silent.

‘I’ll tell you, then. It happens to be the most common criticism made by young ladies and gentlemen such as yourselves, doomed to a course where we begin with excerpts from Beowulf and end with Raymond Carver. Among teachers, such survey courses are sometimes called GTTG: Gallop Through the Glories.’

He screeched cheerfully, also waggling his hands at shoulder height in a yowza-yowza gesture. Most of the kids laughed along, Pete among them.

‘Class verdict on Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal”? This is stupid! “Young Goodman Brown,” by Nathaniel Hawthorne? This is stupid! “Mending Wall,” by Robert Frost? This is moderately stupid! The required excerpt from Moby-Dick? This is extremely stupid!’

More laughter. None of them had read Moby-Dick, but they all knew it was hard and boring. Stupid, in other words.

‘And sometimes!’ Mr Ricker exclaimed, raising one finger and pointing dramatically at the words on the blackboard. ‘Sometimes, my young ladies and gentlemen, the criticism is spot-on. I stand here with my bare face hanging out and admit it. I am required to teach certain antiquities I would rather not teach. I see the loss of enthusiasm in your eyes, and my soul groans. Yes! Groans! But I soldier on, because I know that much of what I teach is not stupid. Even some of the antiquities to which you feel you cannot relate now or ever will, have deep resonance that will eventually reveal itself. Shall I tell you how you judge the not-stupid from the is-stupid? Shall I impart this great secret? Since we have forty minutes left in this class and as yet no grist to grind in the mill of our combined intellects, I believe I will.’

He leaned forward and propped his hands on the desk, his tie swinging like a pendulum. Pete felt that Mr Ricker was looking directly at him, as if he knew – or at least intuited – the tremendous secret Pete was keeping under a pile of blankets in the attic of his house. Something far more important than money.

‘At some point in this course, perhaps even tonight, you will read something difficult, something you only partially understand, and your verdict will be this is stupid. Will I argue when you advance that opinion in class the next day? Why would I do such a useless thing? My time with you is short, only thirty-four weeks of classes, and I will not waste it arguing about the merits of this short story or that poem. Why would I, when all such opinions are subjective, and no final resolution can ever be reached?’

Some of the kids – Gloria was one of them – now looked lost, but Pete understood exactly what Mr Ricker, aka Ricky the Hippie, was talking about, because since starting the notebooks, he had read dozens of critical essays on John Rothstein. Many of them judged Rothstein to be one of the greatest American writers of the twentieth century, right up there with Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Faulkner, and Roth. There were others – a minority, but a vocal one – who asserted that his work was second-rate and hollow. Pete had read a piece in Salon where the writer had called Rothstein ‘king of the wisecrack and the patron saint of fools.’

‘Time is the answer,’ Mr Ricker said on the first day of Pete’s sophomore year. He strode back and forth, antique bellbottoms swishing, occasionally waving his arms. ‘Yes! Time mercilessly culls away the is-stupid from the not-stupid. It is a natural, Darwinian process. It is why the novels of Graham Greene are available in every good bookstore, and the novels of Somerset Maugham are not – those novels still exist, of course, but you must order them, and you would only do that if you knew about them. Most modern readers do not. Raise your hand if you have ever heard of Somerset Maugham. And I’ll spell that for you.’

No hands went up.

Mr Ricker nodded. Rather grimly, it seemed to Pete. ‘Time has decreed that Mr Greene is not-stupid while Mr Maugham is … well, not exactly stupid but forgettable. He wrote some very fine novels, in my opinion – The Moon and Sixpence is remarkable, my young ladies and gentlemen, remarkable – and he also wrote a great deal of excellent short fiction, but none is included in your textbook.

‘Shall I weep over this? Shall I rage, and shake my fists, and proclaim injustice? No. I will not. Such culling is a natural process. It will occur for you, young ladies and gentlemen, although I will be in your rearview mirror by the time it happens. Shall I tell you how it happens? You will read something – perhaps “Dulce et Decorum Est,” by Wilfred Owen. Shall we use that as an example? Why not?’

Then, in a deeper voice that sent chills up Pete’s back and tightened his throat, Mr Ricker cried: ‘“Bent double, like old beggars under sacks, / Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge …” And so on. Cetra-cetra. Some of you will say, This is stupid. Will I break my promise not to argue the point, even though I consider Mr Owen’s poems the greatest to come out of World War I? No! It’s just my opinion, you see, and opinions are like assholes: everybody has one.’

They all roared at that, young ladies and gentlemen alike.

Mr Ricker drew himself up. ‘I may give some of you detentions if you disrupt my class, I have no problem with imposing discipline, but never will I disrespect your opinion. And yet! And yet!’

Up went the finger.

‘Time will pass! Tempus will fugit! Owen’s poem may fall away from your mind, in which case your verdict of is-stupid will have turned out to be correct. For you, at least. But for some of you it will recur. And recur. And recur. Each time it does, the steady march of your maturity will deepen its resonance. Each time that poem steals back into your mind, it will seem a little less stupid and a little more vital. A little more important. Until it shines, young ladies and gentlemen. Until it shines. Thus endeth my opening day peroration, and I ask you to turn to page sixteen in that most excellent tome, Language and Literature.’

One of the stories Mr Ricker assigned that year was ‘The Rocking-Horse Winner,’ by D.H. Lawrence, and sure enough, many of Mr Ricker’s young ladies and gentlemen (including Gloria Moore, of whom Pete was growing tired, in spite of her really excellent breasts) considered it stupid. Pete did not, in large part because events in his life had already caused him to mature beyond his years. As 2013 gave way to 2014 – the year of the famed Polar Vortex, when furnaces all over the upper Midwest went into maximum overdrive, burning money by the bale – that story recurred to him often, and its resonance continued to deepen. And recur.

The family in it seemed to have everything, but they didn’t; there was never quite enough, and the hero of the story, a young boy named Paul, always heard the house whispering, ‘There must be more money! There must be more money!’ Pete Saubers guessed that there were kids who considered that stupid. They were the lucky ones who had never been forced to listen to nightly arkie-barkies about which bills to pay. Or the price of cigarettes.

The young protagonist in the Lawrence story discovered a supernatural way to make money. By riding his toy rocking-horse to the make-believe land of luck, Paul could pick horse-race winners in the real world. He made thousands of dollars, and still the house whispered, ‘There must be more money!’

After one final epic ride on the rocking-horse – and one final big-money pick – Paul dropped dead of a brain hemorrhage or something. Pete didn’t have so much as a headache after finding the buried trunk, but it was still his rocking-horse, wasn’t it? Yes. His very own rocking-horse. But by 2013, the year he met Mr Ricker, the rocking-horse was slowing down. The trunk-money had almost run out.

It had gotten his parents through a rough and scary patch when their marriage might otherwise have crashed and burned; this Pete knew, and he never once regretted playing guardian angel. In the words of that old song, the trunk-money had formed a bridge over troubled water, and things were better – much – on the other side. The worst of the recession was over. Mom was teaching full-time again, her salary three thousand a year better than before. Dad now ran his own small business, not real estate, exactly, but something called real estate search. He had several agencies in the city as clients. Pete didn’t completely understand how it worked, but he knew it was actually making some money, and might make more in the years ahead, if the housing market continued to trend upward. He was agenting a few properties of his own, too. Best of all, he was drug-free and walking well. The crutches had been in the closet for over a year, and he only used his cane on rainy or snowy days when his bones and joints ached. All good. Great, in fact.

And yet, as Mr Ricker said at least once in every class. And yet!

There was Tina to think about, that was one very large and yet. Many of her friends from the old neighborhood on the West Side, including Barbara Robinson, whom Tina had idolized, were going to Chapel Ridge, a private school that had an excellent record when it came to sending kids on to good colleges. Mom had told Tina that she and Dad didn’t see how they could afford to send her there directly from middle school. Maybe she could attend as a sophomore, if their finances continued to improve.

‘But I won’t know anybody by then,’ Tina had said, starting to cry.

‘You’ll know Barbara Robinson,’ Mom said, and Pete (listening from the next room) could tell from the sound of her voice that Mom was on the verge of tears herself. ‘Hilda and Betsy, too.’

But Teens had been a little younger than those girls, and Pete knew only Barbs had been a real friend to his sister back in the West Side days. Hilda Carver and Betsy DeWitt probably didn’t even remember her. Neither would Barbara, in another year or two. Their mother didn’t seem to remember what a big deal high school was, and how quickly you forgot your little-kid friends once you got there.

Tina’s response summed up these thoughts with admirable succinctness. ‘Yeah, but they won’t know me.’

‘Tina—’

‘You have that money!’ Tina cried. ‘That mystery money that comes every month! Why can’t I have some for Chapel Ridge?’

‘Because we’re still catching up from the bad time, honey.’

To this Tina could say nothing, because it was true.

His own college plans were another and yet. Pete knew that to some of his friends, maybe most of them, college seemed as far away as the outer planets of the solar system. But if he wanted a good one (Brown, his mind whispered, English Lit at Brown), that meant making early applications when he was a first-semester senior. The applications themselves cost money, as did the summer class he needed to pick up if he wanted to score at least a 670 on the math part of the SATs. He had a part-time job at the Garner Street Library, but thirty-five bucks a week didn’t go far.

Dad’s business had grown enough to make a downtown office desirable, that was and yet number three. Just a low-rent place on an upper floor, and being close to the action would pay dividends, but it would mean laying out more money, and Pete knew – even though no one said it out loud – that Dad was counting on the mystery cash to carry him through the critical period. They had all come to depend on the mystery cash, and only Pete knew it would be gone before the end of ’14.

And yeah, okay, he had spent some on himself. Not a huge amount – that would have raised questions – but a hundred here and a hundred there. A blazer and a pair of loafers for the class trip to Washington. A few CDs. And books. He had become a fool for books since reading the notebooks and falling in love with John Rothstein. He began with Rothstein’s Jewish contemporaries, like Philip Roth, Saul Bellow, and Irwin Shaw (he thought The Young Lions was fucking awesome, and couldn’t understand why it wasn’t a classic), and spread out from there. He always bought paperbacks, but even those were twelve or fifteen dollars apiece these days, unless you could find them used.

‘The Rocking-Horse Winner’ had resonance, all right, bigtime resonance, because Pete could hear his own house whispering There must be more money … and all too soon there would be less. But money wasn’t all the trunk had contained, was it?

That was another and yet. One Pete Saubers thought about more and more as time passed.

For his end-of-year research paper in Mr Ricker’s Gallop Through the Glories, Pete did a sixteen-page analysis of the Jimmy Gold trilogy, quoting from various reviews and adding in stuff from the few interviews Rothstein had given before retreating to his farm in New Hampshire and going completely dark. He finished by talking about Rothstein’s tour of the German death camps as a reporter for the New York Herald – this for years before publishing the first Jimmy Gold book.

‘I believe that was the most important event of Mr Rothstein’s life,’ Pete wrote. ‘Surely the most important event of his life as a writer. Jimmy’s search for meaning always goes back to what Mr Rothstein saw in those camps, and it’s why, when Jimmy tries to live the life of an ordinary American citizen, he always feels hollow. For me, this is best expressed when he throws an ashtray through the TV in The Runner Slows Down. He does it during a CBS news special about the Holocaust.’

When Mr Ricker returned their papers, a big A+ was scrawled on Pete’s cover, which was a computer-scanned photo of Rothstein as a young man, sitting in Sardi’s with Ernest Hemingway. Below the A+, Mr Ricker had written See me after class.

When the other kids were gone, Mr Ricker looked at Pete so fixedly that Pete was momentarily scared his favorite teacher was going to accuse him of plagiarism. Then Mr Ricker smiled. ‘That is the best student paper I’ve read in my twenty-eight years of teaching. Because it was the most confident, and the most deeply felt.’

Pete’s face heated with pleasure. ‘Thanks. Really. Thanks a lot.’

‘I’d argue with your conclusion, though,’ Mr Ricker said, leaning back in his chair and lacing his fingers together behind his neck. ‘The characterization of Jimmy as “a noble American hero, like Huck Finn,” is not supported by the concluding book of the trilogy. Yes, he throws an ashtray at the television screen, but it’s not an act of heroism. The CBS logo is an eye, you know, and Jimmy’s act is a ritual blinding of his inner eye, the one that sees the truth. That’s not my insight; it’s an almost direct quote from an essay called “The Runner Turns Away,” by John Crowe Ransom. Leslie Fiedler says much the same in Love and Death in the American Novel.’

‘But—’

‘I’m not trying to debunk you, Pete; I’m just saying you need to follow the evidence of any book wherever it leads, and that means not omitting crucial developments that run counter to your thesis. What does Jimmy do after he throws the ashtray through the TV, and after his wife delivers her classic line, “You bastard, how will the kids watch Mickey Mouse now?”’

‘He goes out and buys another TV set, but—’

‘Not just any TV set, but the first color TV set on the block. And then?’

‘He creates the big successful ad campaign for Duzzy-Doo household cleaner. But—’

Mr Ricker raised his eyebrows, waiting for the but. And how could Pete tell him that a year later, Jimmy steals into the agency late one night with matches and a can of kerosene? That Rothstein foreshadows all the protests about Vietnam and civil rights by having Jimmy start a fire that pretty much destroys the building known as the Temple of Advertising? That he hitchhikes out of New York City without a look back, leaving his family behind and striking out for the territory, just like Huck and Jim? He couldn’t say any of that, because it was the story told in The Runner Goes West, a novel that existed only in seventeen closely written notebooks that had lain buried in an old trunk for over thirty years.

‘Go ahead and but me your buts,’ Mr Ricker said equably. ‘There’s nothing I like better than a good book discussion with someone who can hold up his end of the argument. I imagine you’ve already missed your bus, but I’ll be more than happy to give you a ride home.’ He tapped the cover sheet of Pete’s paper, Johnny R. and Ernie H., those twin titans of American literature, with oversized martini glasses raised in a toast. ‘Unsupported conclusion aside – which I put down to a touching desire to see light at the end of an extremely dark final novel – this is extraordinary work. Just extraordinary. So go for it. But me your buts.’

‘But nothing, I guess,’ Pete said. ‘You could be right.’

Only Mr Ricker wasn’t. Any doubt about Jimmy Gold’s capacity to sell out that remained at the end of The Runner Goes West was swept away in the last and longest novel of the series, The Runner Raises the Flag. It was the best book Pete had ever read. Also the saddest.

‘In your paper you don’t go into how Rothstein died.’

‘No.’

‘May I ask why not?’

‘Because it didn’t fit the theme, I guess. And it would have made the paper too long. Also … well … it was such a bummer for him to die that way, getting killed in a stupid burglary.’

‘He shouldn’t have kept cash in the house,’ Mr Ricker said mildly, ‘but he did, and a lot of people knew it. Don’t judge him too harshly for that. Many writers have been stupid and improvident about money. Charles Dickens found himself supporting a family of slackers, including his own father. Samuel Clemens was all but bankrupted by bad real estate transactions. Arthur Conan Doyle lost thousands of dollars to fake mediums and spent thousands more on fake photos of fairies. At least Rothstein’s major work was done. Unless you believe, as some people do—’

Pete looked at his watch. ‘Um, Mr Ricker? I can still catch my bus if I hurry.’

Mr Ricker did that funny yowza-yowza thing with his hands. ‘Go, by all means go. I just wanted to thank you for such a wonderful piece of work … and to offer a friendly caution: when you approach this kind of thing next year – and in college – don’t let your good nature cloud your critical eye. The critical eye should always be cold and clear.’

‘I won’t,’ Pete said, and hurried out.

The last thing he wanted to discuss with Mr Ricker was the possibility that the thieves who had taken John Rothstein’s life had stolen a bunch of unpublished manuscripts as well as money, and maybe destroyed them after deciding they had no value. Once or twice Pete had played with the idea of turning the notebooks over to the police, even though that would almost surely mean his parents would find out where the mystery money had been coming from. The notebooks were, after all, evidence of a crime as well as a literary treasure. But it was an old crime, ancient history. Better to leave well enough alone.

Right?

The bus had already gone, of course, and that meant a two-mile walk home. Pete didn’t mind. He was still glowing from Mr Ricker’s praise, and he had a lot to think about. Rothstein’s unpublished works, mostly. The short stories were uneven, he thought, only a few of them really good, and the poems he’d tried to write were, in Pete’s humble opinion, pretty lame. But those last two Jimmy Gold novels were … well, gold. Judging by the evidence scattered through them, Pete guessed the last one, where Jimmy raises a burning flag at a Washington peace rally, had been finished around 1973, because Nixon was still president when the story ended. That Rothstein had never published the final Gold books (plus yet another novel, this one about the Civil War) blew Pete’s mind. They were so good!

Pete took only one Moleskine at a time down from the attic, reading them with his door closed and an ear cocked for unexpected company when there were other members of his family in the house. He always kept another book handy, and if he heard approaching footsteps, he would slide the notebook under his mattress and pick up the spare. The only time he’d been caught was by Tina, who had the unfortunate habit of walking around in her sock feet.

‘What’s that?’ she’d asked from the doorway.

‘None of your beeswax,’ he had replied, slipping the notebook under his pillow. ‘And if you say anything to Mom or Dad, you’re in trouble with me.’

‘Is it porno?’

‘No!’ Although Mr Rothstein could write some pretty racy scenes, especially for an old guy. For instance the one where Jimmy and these two hippie chicks—

‘Then why don’t you want me to see it?’

‘Because it’s private.’

Her eyes lit up. ‘Is it yours? Are you writing a book?’

‘Maybe. So what if I am?’

‘I think that’s cool! What’s it about?’

‘Bugs having sex on the moon.’

She giggled. ‘I thought you said it wasn’t porno. Can I read it when you’re done?’

‘We’ll see. Just keep your trap shut, okay?’

She had agreed, and one thing you could say for Teens, she rarely broke a promise. That had been two years ago, and Pete was sure she’d forgotten all about it.

Billy Webber came rolling up on a gleaming ten-speed. ‘Hey, Saubers!’ Like almost everyone else (Mr Ricker was an exception), Billy pronounced it Sobbers instead of SOW-bers, but what the hell. It was sort of a dipshit name however you said it. ‘What you doin this summer?’

‘Working at the Garner Street libe.’

‘Still?’

‘I talked em into twenty hours a week.’

‘Fuck, man, you’re too young to be a wage-slave!’

‘I don’t mind,’ Pete said, which was the truth. The libe meant free computer-time, among the other perks, with no one looking over your shoulder. ‘What about you?’

‘Goin to our summer place up in Maine. China Lake. Many cute girls in bikinis, man, and the ones from Massachusetts know what to do.’

Then maybe they can show you, Pete thought snidely, but when Billy held out his palm, Pete slapped him five and watched him go with mild envy. Ten-speed bike under his ass; expensive Nike kicks on his feet; summer place in Maine. It seemed that some people had already caught up from the bad time. Or maybe the bad time had missed them completely. Not so with the Saubers family. They were doing okay, but—

There must be more money, the house had whispered in the Lawrence story. There must be more money. And honey, that was resonance.

Could the notebooks be turned into money? Was there a way? Pete didn’t even like to think about giving them up, but at the same time he recognized how wrong it was to keep them hidden away in the attic. Rothstein’s work, especially the last two Jimmy Gold books, deserved to be shared with the world. They would remake Rothstein’s reputation, Pete was sure of that, but his rep still wasn’t that bad, and besides, it wasn’t the important part. People would like them, that was the important part. Love them, if they were like Pete.

Only, handwritten manuscripts weren’t like untraceable twenties and fifties. Pete would be caught, and he might go to jail. He wasn’t sure exactly what crime he could be charged with – not receiving stolen property, surely, because he hadn’t received it, only found it – but he was positive that trying to sell what wasn’t yours had to be some kind of crime. Donating the notebooks to Rothstein’s alma mater seemed like a possible answer, only he’d have to do it anonymously, or it would all come out and his parents would discover that their son had been supporting them with a murdered man’s stolen money. Besides, for an anonymous donation you got zilch.