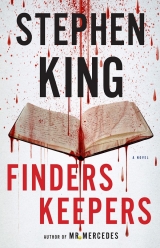

Текст книги "Finders Keepers"

Автор книги: Stephen Edwin King

Жанры:

Триллеры

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

Pete wishes he had never seen that fucking trunk.

He thinks, But I was only trying to do the right thing. Goddammit, that’s all I was trying to do!

Ellen sees the tears standing in the boy’s eyes, and notices for the first time – perhaps because he’s shaved off that silly singles-bar moustache – how thin his face has become. Really just half a step from gaunt. She drops her cell back into her purse and comes out with a packet of tissues. ‘Wipe your face,’ she says.

A voice from the bus calls out, ‘Hey Saubers! D’ja get any?’

‘Shut up, Jeremy,’ Ellen says without turning. Then, to Pete: ‘I should give you a week’s detention for this little stunt, but I’m going to cut you some slack.’

Indeed she is, because a week’s detention would necessitate an oral report to NHS Assistant Principal Waters, who is also School Disciplinarian. Waters would inquire into her own actions, and want to know why she had not sounded the alarm earlier, especially if she were forced to admit that she hadn’t actually seen Pete Saubers since dinner in the restaurant the night before. He had been out of her sight and supervision for nearly a full day, and that was far too long for a school-mandated trip.

‘Thank you, Ms Bran.’

‘Do you think you’re done throwing up?’

‘Yes. There’s nothing left.’

‘Then get on the bus and let’s go home.’

There’s more sarcastic applause as Pete comes up the steps and makes his way down the aisle. He tries to smile, as if everything is okay. All he wants is to get back to Sycamore Street and hide in his room, waiting for tomorrow so he can get this nightmare over with.

10

When Hodges gets home from the hospital, a good-looking young man in a Harvard tee-shirt is sitting on his stoop, reading a thick paperback with a bunch of fighting Greeks or Romans on the cover. Sitting beside him is an Irish setter wearing the sort of happy-go-lucky grin that seems to be the default expression of dogs raised in friendly homes. Both man and dog rise when Hodges pulls into the little lean-to that serves as his garage.

The young man meets him halfway across the lawn, one fisted hand held out. Hodges bumps knuckles with him, thus acknowledging Jerome’s blackness, then shakes his hand, thereby acknowledging his own WASPiness.

Jerome stands back, holding Hodges’s forearms and giving him a once-over. ‘Look at you!’ he exclaims. ‘Skinny as ever was!’

‘I walk,’ Hodges says. ‘And I bought a treadmill for rainy days.’

‘Excellent! You’ll live forever!’

‘I wish,’ Hodges says, and bends down. The dog extends a paw and Hodges shakes it. ‘How you doing, Odell?’

Odell woofs, which presumably means he’s doing fine.

‘Come on in,’ Hodges says. ‘I have Cokes. Unless you’d prefer a beer.’

‘Coke’s fine. I bet Odell would appreciate some water. We walked over. Odell doesn’t walk as fast as he used to.’

‘His bowl’s still under the sink.’

They go in and toast each other with icy glasses of Coca-Cola. Odell laps water, then stretches out in his accustomed place beside the TV. Hodges was an obsessive television watcher during the first months of his retirement, but now the box rarely goes on except for Scott Pelley on The CBS Evening News, or the occasional Indians game.

‘How’s the pacemaker, Bill?’

‘I don’t even know it’s there. Which is just the way I like it. What happened to the big country club dance you were going to in Pittsburgh with what’s-her-name?’

‘That didn’t work out. As far as my parents are concerned, what’s-her-name and I discovered that we are not compatible in terms of our academic and personal interests.’

Hodges raises his eyebrows. ‘Sounds a tad lawyerly for a philosophy major with a minor in ancient cultures.’

Jerome sips his Coke, sprawls his long legs out, and grins. ‘Truth? What’s-her-name – aka Priscilla – was using me to tweak the jealous-bone of her high school boyfriend. And it worked. Told me how sorry she was to get me down there on false pretenses, hopes we can still be friends, so on and so forth. A little embarrassing, but probably all for the best.’ He pauses. ‘She still has all her Barbies and Bratz on a shelf in her room, and I must admit that gave me pause. I guess I wouldn’t mind too much if my folks found out I was the stick she stirred her pot of love-soup with, but if you tell the Barbster, I’ll never hear the end of it.’

‘Mum’s the word,’ Hodges says. ‘So what now? Back to Massachusetts?’

‘Nope, I’m here for the summer. Got a job down on the docks swinging containers.’

‘That is not work for a Harvard man, Jerome.’

‘It is for this one. I got my heavy equipment license last winter, the pay is excellent, and Harvard ain’t cheap, even with a partial scholarship.’ Tyrone Feelgood Delight makes a mercifully brief guest appearance. ‘Dis here black boy goan tote dat barge an’ lift dat bale, Massa Hodges!’ Then back to Jerome, just like that. ‘Who’s mowing your lawn? It looks pretty good. Not Jerome Robinson quality, but pretty good.’

‘Kid from the end of the block,’ Hodges says. ‘Is this just a courtesy call, or …?’

‘Barbara and her friend Tina told me one hell of a story,’ Jerome says. ‘Tina was reluctant to spill it at first, but Barbs talked her into it. She’s good at stuff like that. Listen, you know Tina’s father was hurt in the City Center thing, right?’

‘Yes.’

‘If her big brother was really the one sending cash to keep the fam afloat, good for him … but where did it come from? I can’t figure that one out no matter how hard I try.’

‘Nor can I.’

‘Tina says you’re going to ask him.’

‘After school tomorrow, is the plan.’

‘Is Holly involved?’

‘To an extent. She’s doing background.’

‘Cool!’ Jerome grins big. ‘How about I come with you tomorrow? Get the band back together, man! Play all the hits!’

Hodges considers. ‘I don’t know, Jerome. One guy – a golden oldie like me – might not upset young Mr Saubers too much. Two guys, though, especially when one of them’s a badass black dude who stands six-four—’

‘Fifteen rounds and I’m still pretty!’ Jerome proclaims, waving clasped hands over his head. Odell lays back his ears. ‘Still pretty! That bad ole bear Sonny Liston never touched me! I float like a butterfly, I sting like a …’ He assesses Hodges’s patient expression. ‘Okay, sorry, sometimes I get carried away. Where are you going to wait for him?’

‘Out front was the plan. You know, where the kids actually exit the building?’

‘Not all of them come out that way, and he might not, especially if Tina lets on she talked to you.’ He sees Hodges about to speak and raises a hand. ‘She says she won’t, but big brothers know little sisters, you can take that from a guy who’s got one. If he knows somebody wants to ask him questions, he’s apt to go out the back and cut across the football field to Westfield Street. I could park there, give you a call if I see him.’

‘Do you know what he looks like?’

‘Uh-huh, Tina had a picture in her wallet. Let me be a part of this, Bill. Barbie likes that chick. I liked her too. And it took guts for her to come to you, even with my sister snapping the whip.’

‘I know.’

‘Also, I’m curious as hell. Tina says the money started coming when her bro was only thirteen. A kid that young with access to that much money …’ Jerome shakes his head. ‘I’m not surprised he’s in trouble.’

‘Me, either. I guess if you want to be in, you’re in.’

‘My man!’

This cry necessitates another fist-bump.

‘You went to Northfield, Jerome. Is there any other way he could go out, besides the front and Westfield Street?’

Jerome thinks it over. ‘If he went down to the basement, there’s a door that takes you out to one side, where the smoking area used to be, back in the day. I guess he could go across that, then cut through the auditorium and come out on Garner Street.’

‘I could put Holly there,’ Hodges says thoughtfully.

‘Excellent idea!’ Jerome cries. ‘Gettin the band back together! What I said!’

‘But no approach if you see him,’ Hodges says. ‘Just call. I get to approach. I’ll tell Holly the same thing. Not that she’d be likely to.’

‘As long as we get to hear the story.’

‘If I get it, you’ll get it,’ Hodges says, hoping he has not just made a rash promise. ‘Come by my office in the Turner Building around two, and we’ll move out around two fifteen. Be in position by two forty-five.’

‘You’re sure Holly will be okay with this?’

‘Yes. She’s fine with watching. It’s confrontation that gives her problems.’

‘Not always.’

‘No,’ Hodges says, ‘not always.’

They are both thinking of one confrontation – at the MAC, with Brady Hartsfield – that Holly handled just fine.

Jerome glances at his watch. ‘I have to go. Promised I’d take the Barbster to the mall. She wants a Swatch.’ He rolls his eyes.

Hodges grins. ‘I love your sis, Jerome.’

Jerome grins back. ‘Actually, so do I. Come on, Odell. Let’s shuffle.’

Odell rises and heads for the door. Jerome grasps the knob, then turns back. His grin is gone. ‘Have you been where I think you’ve been?’

‘Probably.’

‘Does Holly know you visit him?’

‘No. And you’re not to tell her. She’d find it vastly upsetting.’

‘Yes. She would. How is he?’

‘The same. Although …’ Hodges is thinking of how the picture fell over. That clack sound.

‘Although what?’

‘Nothing. He’s the same. Do me one favor, okay? Tell Barbara to get in touch if Tina calls and says her brother found out the girls talked to me on Friday.’

‘Will do. See you tomorrow.’

Jerome leaves. Hodges turns on the TV, and is delighted to see the Indians are still on. They’ve tied it up. The game is going into extra innings.

11

Holly spends Sunday evening in her apartment, trying to watch The Godfather Part II on her computer. Usually this would be a very pleasant occupation, because she considers it one of the two or three best movies ever made, right up there with Citizen Kane and Paths of Glory, but tonight she keeps pausing it so she can pace worry-circles around the living room of her apartment. There’s a lot of room to pace. This apartment isn’t as glitzy as the lakeside condo she lived in for a while when she first moved to the city, but it’s in a good neighborhood and plenty big. She can afford the rent; under the terms of her cousin Janey’s will, Holly inherited half a million dollars. Less after taxes, of course, but still a very nice nest egg. And, thanks to her job with Bill Hodges, she can afford to let the nest egg grow.

As she paces, she mutters some of her favorite lines from the movie.

‘I don’t have to wipe everyone out, just my enemies.

‘How do you say banana daiquiri?

‘Your country ain’t your blood, remember that.’

And, of course, the one everyone remembers: ‘I know it was you, Fredo. You broke my heart.’

If she was watching another movie, she would be incanting a different set of quotes. It is a form of self-hypnosis that she has practiced ever since she saw The Sound of Music at the age of seven. (Favorite line from that one: ‘I wonder what grass tastes like.’)

She’s really thinking about the Moleskine notebook Tina’s brother was so quick to hide under his pillow. Bill believes it has nothing to do with the money Pete was sending his parents, but Holly isn’t so sure.

She has kept journals for most of her life, listing all the movies she’s seen, all the books she’s read, the people she’s talked to, the times she gets up, the times she goes to bed. Also her bowel movements, which are coded (after all, someone may see her journals after she’s dead) as WP, which stands for Went Potty. She knows this is OCD behavior – she and her therapist have discussed how obsessive listing is really just another form of magical thinking – but it doesn’t hurt anyone, and if she prefers to keep her lists in Moleskine notebooks, whose business is that besides her own? The point is, she knows from Moleskines, and therefore knows they’re not cheap. Two-fifty will get you a spiral-bound notebook in Walgreens, but a Moleskine with the same number of pages goes for ten bucks. Why would a kid want such an expensive notebook, especially when he came from a cash-strapped family?

‘Doesn’t make sense,’ Holly says. Then, as if just following this train of thought: ‘Leave the gun. Take the cannoli.’ That’s from the original Godfather, but it’s still a good line. One of the best.

Send the money. Keep the notebook.

An expensive notebook that got shoved under the pillow when the little sister appeared unexpectedly in the room. The more Holly thinks about it, the more she thinks there might be something there.

She restarts the movie but can’t follow its well-worn and well-loved path with this notebook stuff rolling around in her head, so Holly does something almost unheard of, at least before bedtime: she turns her computer off. Then she resumes pacing, hands locked together at the small of her back.

Send the money. Keep the notebook.

‘And the lag!’ she exclaims to the empty room. ‘Don’t forget that!’

Yes. The seven months of quiet time between when the money ran out and when the Saubers boy started to get his underpants all in a twist. Because it took him seven months to think up a way to get more money? Holly thinks yes. Holly thinks he got an idea, but it wasn’t a good idea. It was an idea that got him in trouble.

‘What gets people in trouble when it’s about money?’ Holly asks the empty room, pacing faster than ever. ‘Stealing does. So does blackmail.’

Was that it? Did Pete Saubers try to blackmail somebody about something in the Moleskine notebook? Something about the stolen money, maybe? Only how could Pete blackmail someone about that money when he must have stolen it himself?

Holly goes to the telephone, reaches for it, then pulls her hand back. For almost a minute she just stands there, gnawing her lips. She’s not used to taking the initiative in things. Maybe she should call Bill first, and ask him if it’s okay?

‘Bill doesn’t think the notebook’s important, though,’ she tells her living room. ‘I think different. And I can think different if I want to.’

She snatches her cell from the coffee table and calls Tina Saubers before she can lose her nerve.

‘Hello?’ Tina asks cautiously. Almost whispering. ‘Who’s this?’

‘Holly Gibney. You didn’t see my number come up because it’s unlisted. I’m very careful about my number, although I’ll be happy to give it to you, if you want. We can talk anytime, because we’re friends and that’s what friends do. Is your brother back home from his weekend?’

‘Yes. He came in around six, while we were finishing up dinner. Mom said there was still plenty of pot roast and potatoes, she’d heat them up if he wanted, but he said they stopped at Denny’s on the way back. Then he went up to his room. He didn’t even want any strawberry shortcake, and he loves that. I’m really worried about him, Ms Holly.’

‘You can just call me Holly, Tina.’ She hates Ms, thinks it sounds like a mosquito buzzing around your head.

‘Okay.’

‘Did he say anything to you?’

‘Just hi,’ Tina says in a small voice.

‘And you didn’t tell him about coming to the office with Barbara on Friday?’

‘God, no!’

‘Where is he now?’

‘Still in his room. Listening to the Black Keys. I hate the Black Keys.’

‘Yes, me too.’ Holly has no idea who the Black Keys are, although she could name the entire cast of Fargo. (Best line in that one, delivered by Steve Buscemi: ‘Smoke a fuckin peace pipe.’)

‘Tina, does Pete have a special friend he might have talked to about what’s bothering him?’

Tina thinks it over. Holly takes the opportunity to snatch a Nicorette from the open pack beside her computer and pop it into her mouth.

‘I don’t think so,’ Tina says at last. ‘I guess he has friends at school, he’s pretty popular, but his only close friend was Bob Pearson, from down the block? And they moved to Denver last year.’

‘What about a girlfriend?’

‘He used to spend a lot of time with Gloria Moore, but they broke up after Christmas. Pete said she didn’t like to read, and he could never get tight with a girl who didn’t like books.’ Wistfully, Tina adds: ‘I liked Gloria. She showed me how to do my eyes.’

‘Girls don’t need eye makeup until they’re in their thirties,’ Holly says authoritatively, although she has never actually worn any herself. Her mother says only sluts wear eye makeup.

‘Really?’ Tina sounds astonished.

‘What about teachers? Did he have a favorite teacher he might have talked to?’ Holly doubts if an older brother would have talked to his kid sister about favorite teachers, or if the kid sister would have paid any attention even if he did. She asks because it’s the only other thing she can think of.

But Holly doesn’t even hesitate. ‘Ricky the Hippie,’ she says, and giggles.

Holly stops in mid-pace. ‘Who?’

‘Mr Ricker, that’s his real name. Pete said some of the kids call him Ricky the Hippie because he wears these old-time flower-power shirts and ties. Pete had him when he was a freshman. Or maybe a sophomore. I can’t remember. He said Mr Ricker knew what good books were all about. Ms … I mean Holly, is Mr Hodges still going to talk to Pete tomorrow?’

‘Yes. Don’t worry about that.’

But Tina is plenty worried. She sounds on the verge of tears, in fact, and this makes Holly’s stomach contract into a tight little ball. ‘Oh boy. I hope he doesn’t hate me.’

‘He won’t,’ Holly says. She’s chewing her Nicorette at warp speed. ‘Bill will find out what’s wrong and fix it. Then your brother will love you more than ever.’

‘Do you promise?’

‘Yes! Ouch!’

‘What’s wrong?’

‘Nothing.’ She wipes her mouth and looks at a smear of blood on her fingers. ‘I bit my lip. I have to go, Tina. Will you call me if you think of anyone he might have talked to about the money?’

‘There’s no one,’ Tina says forlornly, and starts to cry.

‘Well … okay.’ And because something else seems required: ‘Don’t bother with eye makeup. Your eyes are very pretty as they are. Goodbye.’

She ends the call without waiting for Tina to say anything else and resumes pacing. She spits the wad of Nicorette into the wastebasket by her desk and blots her lip with a tissue, but the bleeding has already stopped.

No close friends and no steady girl. No names except for that one teacher.

Holly sits down and powers up her computer again. She opens Firefox, goes to the Northfield High website, clicks OUR FACULTY, and there is Howard Ricker, wearing a flower-patterned shirt with billowy sleeves, just like Tina said. Also a very ridiculous tie. Is it really so impossible that Pete Saubers said something to his favorite English teacher, especially if it had to do with whatever he was writing (or reading) in a Moleskine notebook?

A few clicks and she has Howard Ricker’s telephone number on her computer screen. It’s still early, but she can’t bring herself to cold-call a complete stranger. Phoning Tina was hard enough, and that call ended in tears.

I’ll tell Bill tomorrow, she decides. He can call Ricky the Hippie if he thinks it’s worth doing.

She goes back to her voluminous movie folder and is soon once more lost in The Godfather Part II.

12

Morris visits another computer café that Sunday night, and does his own quick bit of research. When he’s found what he wants, he fishes out the piece of notepaper with Peter Saubers’s cell number on it, and jots down Andrew Halliday’s address. Coleridge Street is on the West Side. In the seventies, that was a middle-class and mostly white enclave where all the houses tried to look a little more expensive than they actually were, and as a result all ended up looking pretty much the same.

A quick visit to several local real estate sites shows Morris that things over there haven’t changed much, although an upscale shopping center has been added: Valley Plaza. Andy’s car may still be parked at his house out there. Of course it might be in a space behind his shop, Morris never checked (Christ, you can’t check everything, he thinks), but that seems unlikely. Why would you put up with the hassle of driving three miles into the city every morning and three miles back every night, in rush-hour traffic, when you could buy a thirty-day bus-pass for ten dollars, or a six-month’s pass for fifty? Morris has the keys to his old pal’s house, although he’d never try using them; the house is a lot more likely to be alarmed than the Birch Street Rec.

But he also has the keys to Andy’s car, and a car might come in handy.

He walks back to Bugshit Manor, convinced that McFarland will be waiting for him there, and not content just to make Morris pee in the little cup. No, not this time. This time he’ll also want to toss his room, and when he does he’ll find the Tuff Tote with the stolen computer and the bloody shirt and shoes inside. Not to mention the envelope of money he took from his old pal’s desk.

I’d kill him, thinks Morris – who is now (in his own mind, at least) Morris the Wolf.

Only he couldn’t use the gun, plenty of people in Bugshit Manor know what a gunshot sounds like, even a polite ka-pow from a little faggot gun like his old pal’s P238, and he left the hatchet in Andy’s office. That might not do the job even if he did have it. McFarland is big like Andy, but not all puddly-fat like Andy. McFarland looks strong.

That’s okay, Morris tells himself. That shit don’t mean shit. Because an old wolf is a crafty wolf, and that’s what I have to be now: crafty.

McFarland isn’t waiting on the stoop, but before Morris can breathe a sigh of relief, he becomes convinced that his PO will be waiting for him upstairs. Not in the hall, either. He’s probably got a passkey that lets him into every room in this fucked-up, piss-smelling place.

Try me, he thinks. You just try me, you sonofabitch.

But the door is locked, the room is empty, and it doesn’t look like it’s been searched, although he supposes if McFarland did it carefully … craftily—

But then Morris calls himself an idiot. If McFarland had searched his room, he would have been waiting with a couple of cops, and the cops would have handcuffs.

Nevertheless, he snatches open the closet door to make sure the Tuff Totes are where he left them. They are. He takes out the money and counts it. Six hundred and forty dollars. Not great, not even close to what was in Rothstein’s safe, but not bad. He puts it back, zips the bag shut, then sits on his bed and holds up his hands. They are shaking.

I have to get that stuff out of here, he thinks, and I have to do it tomorrow morning. But get it out to where?

Morris lies down on his bed and looks up the ceiling, thinking. At last he falls asleep.

13

Monday dawns clear and warm, the thermometer in front of City Center reading seventy before the sun is even fully over the horizon. School is still in session and will be for the next two weeks, but today is going to be the first real sizzler of the summer, the kind of day that makes people wipe the backs of their necks and squint at the sun and talk about global warming.

When Hodges gets to his office at eight thirty, Holly is already there. She tells him about her conversation with Tina last night, and asks if Hodges will talk to Howard Ricker, aka Ricky the Hippie, if he can’t get the story of the money from Pete himself. Hodges agrees to this, and tells Holly that was good thinking (she glows at this), but privately believes talking to Ricker won’t be necessary. If he can’t crack a seventeen-year-old kid – one who’s probably dying to tell someone what’s been weighing him down – he needs to quit working and move to Florida, home of so many retired cops.

He asks Holly if she’ll watch for the Saubers boy on Garner Street when school lets out this afternoon. She agrees, as long as she doesn’t have to talk to him herself.

‘You won’t,’ Hodges assures her. ‘If you see him, all you need to do is call me. I’ll come around the block and cut him off. Have we got pix of him?’

‘I’ve downloaded half a dozen to my computer. Five from the yearbook and one from the Garner Street Library, where he works as a student aide, or something. Come and look.’

The best photo – a portrait shot in which Pete Saubers is wearing a tie and a dark sportcoat – identifies him as CLASS OF ’15 STUDENT VICE PRESIDENT. He’s dark-haired and good-looking. The resemblance to his kid sister isn’t striking, but it’s there, all right. Intelligent blue eyes look levelly out at Hodges. In them is the faintest glint of humor.

‘Can you email these to Jerome?’

‘Already done.’ Holly smiles, and Hodges thinks – as he always does – that she should do it more often. When she smiles, Holly is almost beautiful. With a little mascara around her eyes, she probably would be. ‘Gee, it’ll be good to see Jerome again.’

‘What have I got this morning, Holly? Anything?’

‘Court at ten o’clock. The assault thing.’

‘Oh, right. The guy who tuned up on his brother-in-law. Belson the Bald Beater.’

‘It’s not nice to call people names,’ Holly says.

This is probably true, but court is always an annoyance, and having to go there today is particularly trying, even though it will probably take no more than an hour, unless Judge Wiggins has slowed down since Hodges was on the cops. Pete Huntley used to call Brenda Wiggins FedEx, because she always delivered on time.

The Bald Beater is James Belson, whose picture should probably be next to white trash in the dictionary. He’s a resident of the city’s Edgemont Avenue district, sometimes referred to as Hillbilly Heaven. As part of his contract with one of the city’s car dealerships, Hodges was hired to repo Belson’s Acura MDX, on which Belson had ceased making payments some months before. When Hodges arrived at Belson’s ramshackle house, Belson wasn’t there. Neither was the car. Mrs Belson – a lady who looked rode hard and put away still damp – told him the Acura had been stolen by her brother Howie. She gave him the address, which was also in Hillbilly Heaven.

‘I got no love for Howie,’ she told Hodges, ‘but you might ought to get over before Jimmy kills him. When Jimmy’s mad, he don’t believe in talk. He goes right to beatin.’

When Hodges arrived, James Belson was indeed beating on Howie. He was doing this work with a rake-handle, his bald head gleaming with sweat in the sunlight. Belson’s brother-in-law was lying in his weedy driveway by the rear bumper of the Acura, kicking ineffectually at Belson and trying to shield his bleeding face and broken nose with his hands. Hodges stepped up behind Belson and soothed him with the Happy Slapper. The Acura was back on the car dealership’s lot by noon, and Belson the Bald Beater was now up on assault.

‘His lawyer is going to try to make you look like the bad guy,’ Holly says. ‘He’s going to ask how you subdued Mr Belson. You need to be ready for that, Bill.’

‘Oh, for goodness sake,’ Hodges says. ‘I thumped him one to keep him from killing his brother-in-law, that’s all. Applied acceptable force and practiced restraint.’

‘But you used a weapon to do it. A sock loaded with ball bearings, to be exact.’

‘True, but Belson doesn’t know that. His back was turned. And the other guy was semiconscious at best.’

‘Okay …’ But she looks worried and her teeth are working at the spot she nipped while talking to Tina. ‘I just don’t want you to get in trouble. Promise me you’ll keep your temper and not shout, or wave your arms, or—’

‘Holly.’ He takes her by the shoulders. Gently. ‘Go outside. Smoke a cigarette. Chillax. All will be well in court this morning and with Pete Saubers this afternoon.’

She looks up at him, wide-eyed. ‘Do you promise?’

‘Yes.’

‘All right. I’ll just smoke half a cigarette.’ She heads for the door, rummaging in her bag. ‘We’re going to have such a busy day.’

‘I suppose we are. One other thing before you go.’

She turns back, questioning.

‘You should smile more often. You’re beautiful when you smile.’

Holly blushes all the way to her hairline and hurries out. But she’s smiling again, and that makes Hodges happy.

14

Morris is also having a busy day, and busy is good. As long as he’s in motion, the doubts and fears don’t have a chance to creep in. It helps that he woke up absolutely sure of one thing: this is the day he becomes a wolf for real. He’s all done patching up the Culture and Arts Center’s outdated computer filing system so his fat fuck of a boss can look good to his boss, and he’s done being Ellis McFarland’s pet lamb, too. No more baa-ing yes sir and no sir and three bags full sir each time McFarland shows up. Parole is finished. As soon as he has the Rothstein notebooks, he’s getting the hell out of this pisspot of a city. He has no interest in going north to Canada, but that leaves the whole Lower Forty-Eight. He thinks maybe he’ll opt for New England. Who knows, maybe even New Hampshire. Reading the notebooks there, near the same mountains Rothstein must have looked at while he was writing – that had a certain novelistic roundness, didn’t it? Yes, and that was the great thing about novels: that roundness. The way things always balanced out in the end. He should have known Rothstein couldn’t leave Jimmy working for that fucking ad agency, because there was no roundness in that, just a big old scoop of ugly. Maybe, deep down in his heart, Morris had known it. Maybe it was what kept him sane all those years.

He’s never felt saner in his life.

When he doesn’t show up for work this morning, his fat fuck boss will probably call McFarland. That, at least, is what he’s supposed to do in the event of an unexplained absence. So Morris has to disappear. Duck under the radar. Go dark.

Fine.

Terrific, in fact.

At eight this morning, he takes the Main Street bus, rides all the way to its turnaround point where Lower Main ends, and then strolls down to Lacemaker Lane. Morris has put on his only sportcoat and his only tie, and they’re good enough for him to not look out of place here, even though it’s too early for any of the fancy-schmancy stores to have opened. He turns down the alley between Andrew Halliday Rare Editions and the shop next door, La Bella Flora Children’s Boutique. There are three parking spaces in the small courtyard behind the buildings, two for the clothing shop and one for the bookshop. There’s a Volvo in one of the La Bella Flora spots. The other one is empty. So is the space reserved for Andrew Halliday.