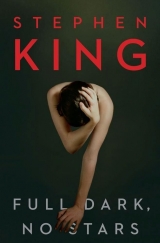

Текст книги "Full dark, no stars"

Автор книги: Stephen Edwin King

Жанр:

Ужасы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

In words of one syllable, you have to do the dirty to someone else if the dirty is to be lifted from you.

But stealing a single hypertension pill wasn’t exactly doing the dirty. Was it?

Elvid, meanwhile, was yanking his big umbrella closed. And when it was furled, Streeter observed an amazing and disheartening fact: it wasn’t yellow at all. It was as gray as the sky. Summer was almost over.

“Most of my clients are perfectly satisfied, perfectly happy. Is that what you want to hear?”

It was… and wasn’t.

“I sense you have a more pertinent question,” Elvid said. “If you want an answer, quit beating around the bush and ask it. It’s going to rain, and I want to get undercover before it does. The last thing I need at my age is bronchitis.”

“Where’s your car?”

“Oh, was that your question?” Elvid sneered openly at him. His cheeks were lean, not in the least pudgy, and his eyes turned up at the corners, where the whites shaded to an unpleasant and-yes, it was true-cancerous black. He looked like the world’s least pleasant clown, with half his makeup removed.

“Your teeth,” Streeter said stupidly. “They have points.”

“Your question, Mr. Streeter!”

“Is Tom Goodhugh going to get cancer?”

Elvid gaped for a moment, then started to giggle. The sound was wheezy, dusty, and unpleasant-like a dying calliope.

“No, Dave,” he said. “Tom Goodhugh isn’t going to get cancer. Not him.”

“What, then? What?”

The contempt with which Elvid surveyed him made Streeter’s bones feel weak-as if holes had been eaten in them by some painless but terribly corrosive acid. “Why would you care? You hate him, you said so yourself.”

“But-”

“Watch. Wait. Enjoy. And take this.” He handed Streeter a business card. Written on it was THE NON-SECTARIAN CHILDREN’S FUND and the address of a bank in the Cayman Islands.

“Tax haven,” Elvid said. “You’ll send my fifteen percent there. If you short me, I’ll know. And then woe is you, kiddo.”

“What if my wife finds out and asks questions?”

“Your wife has a personal checkbook. Beyond that, she never looks at a thing. She trusts you. Am I right?”

“Well…” Streeter observed with no surprise that the raindrops striking Elvid’s hands and arms smoked and sizzled. “Yes.”

“Of course I am. Our dealing is done. Get out of here and go back to your wife. I’m sure she’ll welcome you with open arms. Take her to bed. Stick your mortal penis in her and pretend she’s your best friend’s wife. You don’t deserve her, but lucky you.”

“What if I want to take it back,” Streeter whispered.

Elvid favored him with a stony smile that revealed a jutting ring of cannibal teeth. “You can’t,” he said.

That was in August of 2001, less than a month before the fall of the Towers.

In December (on the same day Winona Ryder was busted for shoplifting, in fact), Dr. Roderick Henderson proclaimed Dave Streeter cancer-free-and, in addition, a bona fide miracle of the modern age.

“I have no explanation for this,” Henderson said.

Streeter did, but kept his silence.

Their consultation took place in Henderson’s office. At Derry Home Hospital, in the conference room where Streeter had looked at the first pictures of his miraculously cured body, Norma Goodhugh sat in the same chair where Streeter had sat, looking at less pleasant MRI scans. She listened numbly as her doctor told her-as gently as possible-that the lump in her left breast was indeed cancer, and it had spread to her lymph nodes.

“The situation is bad, but not hopeless,” the doctor said, reaching across the table to take Norma’s cold hand. He smiled. “We’ll want to start you on chemotherapy immediately.”

In June of the following year, Streeter finally got his promotion. May Streeter was admitted to the Columbia School of Journalism grad school. Streeter and his wife took a long-deferred Hawaii vacation to celebrate. They made love many times. On their last day in Maui, Tom Goodhugh called. The connection was bad and he could hardly talk, but the message got through: Norma had died.

“We’ll be there for you,” Streeter promised.

When he told Janet the news, she collapsed on the hotel bed, weeping with her hands over her face. Streeter lay down beside her, held her close, and thought: Well, we were going home, anyway. And although he felt bad about Norma (and sort of bad for Tom), there was an upside: they had missed bug season, which could be a bitch in Derry.

In December, Streeter sent a check for just over fifteen thousand dollars to The Non-Sectarian Children’s Fund. He took it as a deduction on his tax return.

In 2003, Justin Streeter made the Dean’s List at Brown and-as a lark-invented a video game called Walk Fido Home. The object of the game was to get your leashed dog back from the mall while avoiding bad drivers, objects falling from tenth-story balconies, and a pack of crazed old ladies who called themselves the Canine-Killing Grannies. To Streeter it sounded like a joke (and Justin assured them it was meant as a satire), but Games, Inc. took one look and paid their handsome, good-humored son seven hundred and fifty thousand dollars for the rights. Plus royalties. Jus bought his parents matching Toyota Pathfinder SUVs, pink for the lady, blue for the gentleman. Janet wept and hugged him and called him a foolish, impetuous, generous, and altogether splendid boy. Streeter took him to Roxie’s Tavern and bought him a Spotted Hen Microbrew.

In October, Carl Goodhugh’s roommate at Emerson came back from class to find Carl facedown on the kitchen floor of their apartment with the grilled cheese sandwich he’d been making for himself still smoking in the frypan. Although only twenty-two years of age, Carl had suffered a heart attack. The doctors attending the case pinpointed a congenital heart defect-something about a thin atrial wall-that had gone undetected. Carl didn’t die; his roommate got to him just in time and knew CPR. But he suffered oxygen deprivation, and the bright, handsome, physically agile young man who had not long before toured Europe with Justin Streeter became a shuffling shadow of his former self. He was not always continent, he got lost if he wandered more than a block or two from home (he had moved back with his still-grieving father), and his speech had become a blurred blare that only Tom could understand. Goodhugh hired a companion for him. The companion administered physical therapy and saw that Carl changed his clothes. He also took Carl on biweekly “outings.” The most common “outing” was to Wishful Dishful Ice Cream, where Carl would always get a pistachio cone and smear it all over his face. Afterward the companion would clean him up, patiently, with Wet-Naps.

Janet stopped going with Streeter to dinner at Tom’s. “I can’t bear it,” she confessed. “It’s not the way Carl shuffles, or how he sometimes wets his pants-it’s the look in his eyes, as if he remembers how he was, and can’t quite remember how he got to where he is now. And… I don’t know… there’s always something hopeful in his face that makes me feel like everything in life is a joke.”

Streeter knew what she meant, and often considered the idea during his dinners with his old friend (without Norma to cook, it was now mostly takeout). He enjoyed watching Tom feed his damaged son, and he enjoyed the hopeful look on Carl’s face. The one that said, “This is all a dream I’m having, and soon I’ll wake up.” Jan was right, it was a joke, but it was sort of a good joke.

If you really thought about it.

In 2004, May Streeter got a job with the Boston Globe and declared herself the happiest girl in the USA. Justin Streeter created Rock the House, which would be a perennial bestseller until the advent of Guitar Hero made it obsolete. By then Jus had moved on to a music composition computer program called You Moog Me, Baby. Streeter himself was appointed manager of his bank branch, and there were rumors of a regional post in his future. He took Janet to Canc?n, and they had a fabulous time. She began calling him “my nuzzle-bunny.”

Tom’s accountant at Goodhugh Waste Removal embezzled two million dollars and departed for parts unknown. The subsequent accounting review revealed that the business was on very shaky ground; that bad old accountant had been nibbling away for years, it seemed.

Nibbling? Streeter thought, reading the story in The Derry News. Taking it a chomp at a time is more like it.

Tom no longer looked thirty-five; he looked sixty. And must have known it, because he stopped dying his hair. Streeter was delighted to see that it hadn’t gone white underneath the artificial color; Goodhugh’s hair was the dull and listless gray of Elvid’s umbrella when he had furled it. The hair-color, Streeter decided, of the old men you see sitting on park benches and feeding the pigeons. Call it Just For Losers.

In 2005, Jacob the football player, who had gone to work in his father’s dying company instead of to college (which he could have attended on a full-boat athletic scholarship), met a girl and got married. Bubbly little brunette named Cammy Dorrington. Streeter and his wife agreed it was a beautiful ceremony, even though Carl Goodhugh hooted, gurgled, and burbled all the way through it, and even though Goodhugh’s oldest child-Gracie-tripped over the hem of her dress on the church steps as she was leaving, fell down, and broke her leg in two places. Until that happened, Tom Goodhugh had looked almost like his former self. Happy, in other words. Streeter did not begrudge him a little happiness. He supposed that even in hell, people got an occasional sip of water, if only so they could appreciate the full horror of unrequited thirst when it set in again.

The honeymooning couple went to Belize. I’ll bet it rains the whole time, Streeter thought. It didn’t, but Jacob spent most of the week in a run-down hospital, suffering from violent gastroenteritis and pooping into paper didies. He had only drunk bottled water, but then forgot and brushed his teeth from the tap. “My own darn fault,” he said.

Over eight hundred US troops died in Iraq. Bad luck for those boys and girls.

Tom Goodhugh began to suffer from gout, developed a limp, started using a cane.

That year’s check to The Non-Sectarian Children’s Fund was of an extremely good size, but Streeter didn’t begrudge it. It was more blessed to give than to receive. All the best people said so.

In 2006, Tom’s daughter Gracie fell victim to pyorrhea and lost all her teeth. She also lost her sense of smell. One night shortly thereafter, at Goodhugh and Streeter’s weekly dinner (it was just the two men; Carl’s attendant had taken Carl on an “outing”), Tom Goodhugh broke down in tears. He had given up microbrews in favor of Bombay Sapphire gin, and he was very drunk. “I don’t understand what’s happened to me!” he sobbed. “I feel like… I don’t know… fucking Job!”

Streeter took him in his arms and comforted him. He told his old friend that clouds always roll in, and sooner or later they always roll out.

“Well, these clouds have been here a fuck of a long time!” Goodhugh cried, and thumped Streeter on the back with a closed fist. Streeter didn’t mind. His old friend wasn’t as strong as he used to be.

Charlie Sheen, Tori Spelling, and David Hasselhoff got divorces, but in Derry, David and Janet Streeter celebrated their thirtieth wedding anniversary. There was a party. Toward the end of it, Streeter escorted his wife out back. He had arranged fireworks. Everybody applauded except for Carl Goodhugh. He tried, but kept missing his hands. Finally the former Emerson student gave up on the clapping thing and pointed at the sky, hooting.

In 2007, Kiefer Sutherland went to jail (not for the first time) on DUI charges, and Gracie Goodhugh Dickerson’s husband was killed in a car crash. A drunk driver veered into his lane while Andy Dickerson was on his way home from work. The good news was that the drunk wasn’t Kiefer Sutherland. The bad news was that Gracie Dickerson was four months pregnant and broke. Her husband had let his life insurance lapse to save on expenses. Gracie moved back in with her father and her brother Carl.

“With their luck, that baby will be born deformed,” Streeter said one night as he and his wife lay in bed after making love.

“Hush!” Janet cried, shocked.

“If you say it, it won’t come true,” Streeter explained, and soon the two nuzzle-bunnies were asleep in each other’s arms.

That year’s check to the Children’s Fund was for thirty thousand dollars. Streeter wrote it without a qualm.

Gracie’s baby came at the height of a February snowstorm in 2008. The good news was that it wasn’t deformed. The bad news was that it was born dead. That damned family heart defect. Gracie-toothless, husbandless, and unable to smell anything-dropped into a deep depression. Streeter thought that demonstrated her basic sanity. If she had gone around whistling “Don’t Worry, Be Happy,” he would have advised Tom to lock up all the sharp objects in the house.

A plane carrying two members of the rock band Blink-182 crashed. Bad news, four people died. Good news, the rockers actually survived for a change… although one of them would die not much later.

“I have offended God,” Tom said at one of the dinners the two men now called their “bachelor nights.” Streeter had brought spaghetti from Cara Mama, and cleaned his plate. Tom Goodhugh barely touched his. In the other room, Gracie and Carl were watching American Idol, Gracie in silence, the former Emerson student hooting and gabbling. “I don’t know how, but I have.”

“Don’t say that, because it isn’t true.”

“You don’t know that.”

“I do,” Streeter said emphatically. “It’s foolish talk.”

“If you say so, buddy.” Tom’s eyes filled with tears. They rolled down his cheeks. One clung to the line of his unshaven jaw, dangled there for a moment, then plinked into his uneaten spaghetti. “Thank God for Jacob. He’s all right. Working for a TV station in Boston these days, and his wife’s in accounting at Brigham and Women’s. They see May once in awhile.”

“Great news,” Streeter said heartily, hoping Jake wouldn’t somehow contaminate his daughter with his company.

“And you still come and see me. I understand why Jan doesn’t, and I don’t hold it against her, but… I look forward to these nights. They’re like a link to the old days.”

Yes, Streeter thought, the old days when you had everything and I had cancer.

“You’ll always have me,” he said, and clasped one of Goodhugh’s slightly trembling hands in both of his own. “Friends to the end.”

2008, what a year! Holy fuck! China hosted the Olympics! Chris Brown and Rihanna became nuzzle-bunnies! Banks collapsed! The stock market tanked! And in November, the EPA closed Mount Trashmore, Tom Goodhugh’s last source of income. The government stated its intention to bring suit in matters having to do with groundwater pollution and illegal dumping of medical wastes. The Derry News hinted that there might even be criminal action.

Streeter often drove out along the Harris Avenue Extension in the evenings, looking for a certain yellow umbrella. He didn’t want to dicker; he only wanted to shoot the shit. But he never saw the umbrella or its owner. He was disappointed but not surprised. Deal-makers were like sharks; they had to keep moving or they’d die.

He wrote a check and sent it to the bank in the Caymans.

In 2009, Chris Brown beat the hell out of his Number One Nuzzle-Bunny after the Grammy Awards, and a few weeks later, Jacob Goodhugh the ex-football player beat the hell out of his bubbly wife Cammy after Cammy found a certain lady’s undergarment and half a gram of cocaine in Jacob’s jacket pocket. Lying on the floor, crying, she called him a son of a bitch. Jacob responded by stabbing her in the abdomen with a meat fork. He regretted it at once and called 911, but the damage was done; he’d punctured her stomach in two places. He told the police later that he remembered none of this. He was in a blackout, he said.

His court-appointed lawyer was too dumb to get a bail reduction. Jake Goodhugh appealed to his father, who was hardly able to pay his heating bills, let alone provide high-priced Boston legal talent for his spouse-abusing son. Goodhugh turned to Streeter, who didn’t let his old friend get a dozen words into his painfully rehearsed speech before saying you bet. He still remembered the way Jacob had so unselfconsciously kissed his old man’s cheek. Also, paying the legal fees allowed him to question the lawyer about Jake’s mental state, which wasn’t good; he was racked with guilt and deeply depressed. The lawyer told Streeter that the boy would probably get five years, hopefully with three of them suspended.

When he gets out, he can go home, Streeter thought. He can watch American Idol with Gracie and Carl, if it’s still on. It probably will be.

“I’ve got my insurance,” Tom Goodhugh said one night. He had lost a lot of weight, and his clothes bagged on him. His eyes were bleary. He had developed psoriasis, and scratched restlessly at his arms, leaving long red marks on the white skin. “I’d kill myself if I thought I could get away with making it look like an accident.”

“I don’t want to hear talk like that,” Streeter said. “Things will turn around.”

In June, Michael Jackson kicked the bucket. In August, Carl Goodhugh went and did him likewise, choking to death on a piece of apple. The companion might have performed the Heimlich maneuver and saved him, but the companion had been let go due to lack of funds sixteen months before. Gracie heard Carl gurgling but said she thought “it was just his usual bullshit.” The good news was Carl also had life insurance. Just a small policy, but enough to bury him.

After the funeral (Tom Goodhugh sobbed all the way through it, holding onto his old friend for support), Streeter had a generous impulse. He found Kiefer Sutherland’s studio address and sent him an AA Big Book. It would probably go right in the trash, he knew (along with the countless other Big Books fans had sent him over the years), but you never knew. Sometimes miracles happened.

***

In early September of 2009, on a hot summer evening, Streeter and Janet rode out to the road that runs along the back end of Derry’s airport. No one was doing business on the graveled square outside the Cyclone fence, so he parked his fine blue Pathfinder there and put his arm around his wife, whom he loved more deeply and completely than ever. The sun was going down in a red ball.

He turned to Janet and saw that she was crying. He tilted her chin toward him and solemnly kissed the tears away. That made her smile.

“What is it, honey?”

“I was thinking about the Goodhughs. I’ve never known a family to have such a run of bad luck. Bad luck?” She laughed. “Black luck is more like it.”

“I haven’t, either,” he said, “but it happens all the time. One of the women killed in the Mumbai attacks was pregnant, did you know that? Her two-year-old lived, but the kid was beaten within an inch of his life. And-”

She put two fingers to her lips. “Hush. No more. Life’s not fair. We know that.”

“But it is!” Streeter spoke earnestly. In the sunset light his face was ruddy and healthy. “Just look at me. There was a time when you never thought I’d live to see 2009, isn’t that true?”

“Yes, but-”

“And the marriage, still as strong as an oak door. Or am I wrong?”

She shook her head. He wasn’t wrong.

“You’ve started selling freelance pieces to The Derry News, May’s going great guns with the Globe, and our son the geek is a media mogul at twenty-five.”

She began to smile again. Streeter was glad. He hated to see her blue.

“Life is fair. We all get the same nine-month shake in the box, and then the dice roll. Some people get a run of sevens. Some people, unfortunately, get snake-eyes. It’s just how the world is.”

She put her arms around him. “I love you, sweetie. You always look on the bright side.”

Streeter shrugged modestly. “The law of averages favors optimists, any banker would tell you that. Things have a way of balancing out in the end.”

Venus came into view above the airport, glimmering against the darkening blue.

“Wish!” Streeter commanded.

Janet laughed and shook her head. “What would I wish for? I have everything I want.”

“Me too,” Streeter said, and then, with his eyes fixed firmly on Venus, he wished for more.