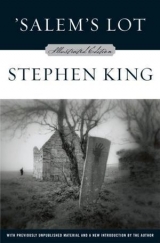

Текст книги "Salem's Lot"

Автор книги: Stephen Edwin King

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

ROUTE 12 JERUSALEM’S LOT

CUMBERLAND CUMBERLAND CTR

A sudden blackness came over him, dousing his good spirits like sand on fire. He had been subject to these since (his mind tried to speak Miranda’s name and he would not let it) the bad time and was used to fending them off, but this one swept over him with a savage power that was dismaying.

What was he doing, coming back to a town where he had lived for four years as a boy, trying to recapture something that was irrevocably lost? What magic could he expect to recapture by walking roads that he had once walked as a boy and were probably asphalted and straightened and logged off and littered with tourist beer cans? The magic was gone, both white and black. It had all gone down the chutes on that night when the motorcycle had gone out of control and then there was the yellow moving van, growing and growing, his wife Miranda’s scream, cut off with sudden finality when—

The exit came up on his right, and for a moment he considered driving right past it, continuing on to Chamberlain or Lewiston, stopping for lunch, and then turning around and going back. But back where? Home? That was a laugh. If there was a home, it had been here. Even if it had only been four years, it was his.

He signaled, slowed the Citroën, and went up the ramp. Toward the top, where the turnpike ramp joined Route 12 (which became Jointner Avenue closer to town), he glanced up toward the horizon. What he saw there made him jam the brakes on with both feet. The Citroën shuddered to a stop and stalled.

The trees, mostly pine and spruce, rose in gentle slopes toward the east, seeming to almost crowd against the sky at the limit of vision. From here the town was not visible. Only the trees, and in the distance, where those trees rose against the sky, the peaked, gabled roof of the Marsten House.

He gazed at it, fascinated. Warring emotions crossed his face with kaleidoscopic swiftness.

“Still here,” he murmured aloud. “By God.”

He looked down at his arms. They had broken out in goose flesh.

TWO

He deliberately skirted town, crossing into Cumberland and then coming back into ’salem’s Lot from the west, taking the Burns Road. He was amazed by how little things had changed out here. There were a few new houses he didn’t remember, there was a tavern called Dell’s just over the town line, and a pair of fresh gravel quarries. A good deal of the hardwood had been pulped over. But the old tin sign pointing the way to the town dump was still there, and the road itself was still unpaved, full of chuckholes and washboards, and he could see Schoolyard Hill through the slash in the trees where the Central Maine Power pylons ran on a northwest to southeast line. The Griffen farm was still there, although the barn had been enlarged. He wondered if they still bottled and sold their own milk. The logo had been a smiling cow under the name brand: “Sunshine Milk from the Griffen Farms!” He smiled. He had splashed a lot of that milk on his corn flakes at Aunt Cindy’s house.

He turned left onto the Brooks Road, passed the wrought-iron gates and the low fieldstone wall surrounding Harmony Hill Cemetery, and then went down the steep grade and started up the far side—the side known as Marsten’s Hill.

At the top, the trees fell away on both sides of the road. On the right, you could look right down into the town proper—Ben’s first view of it. On the left, the Marsten House. He pulled over and got out of the car.

It was just the same. There was no difference, not at all. He might have last seen it yesterday.

The witch grass grew wild and tall in the front yard, obscuring the old, frost-heaved flagstones that led to the porch. Chirring crickets sang in it, and he could see grasshoppers jumping in erratic parabolas.

The house itself looked toward town. It was huge and rambling and sagging, its windows haphazardly boarded shut, giving it that sinister look of all old houses that have been empty for a long time. The paint had been weathered away, giving the house a uniform gray look. Windstorms had ripped many of the shingles off, and a heavy snowfall had punched in the west corner of the main roof, giving it a slumped, hunched look. A tattered no-trespassing sign was nailed to the right-hand newel post.

He felt a strong urge to walk up that overgrown path, past the crickets and hoppers that would jump around his shoes, climb the porch, peek between the haphazard boards into the hallway or the front room. Perhaps try the front door. If it was unlocked, go in.

He swallowed and stared up at the house, almost hypnotized. It stared back at him with idiot indifference.

You walked down the hall, smelling wet plaster and rotting wallpaper, and mice would skitter in the walls. There would still be a lot of junk lying around, and you might pick something up, a paperweight maybe, and put it in your pocket. Then, at the end of the hall, instead of going through into the kitchen, you could turn left and go up the stairs, your feet gritting in the plaster dust which had sifted down from the ceiling over the years. There were fourteen steps, exactly fourteen. But the top one was smaller, out of proportion, as if it had been added to avoid the evil number. At the top of the stairs you stand on the landing, looking down the hall toward a closed door. And if you walk down the hall toward it, watching as if from outside yourself as the door gets closer and larger, you can reach out your hand and put it on the tarnished silver knob—

He turned away from the house, a straw-dry whistle of air slipping from his mouth. Not yet. Later, perhaps, but not yet. For now it was enough to know that all of that was still here. It had waited for him. He put his hands on the hood of his car and looked out over the town. He could find out down there who was handling the Marsten House, and perhaps lease it. The kitchen would make an adequate writing room and he could bunk down in the front parlor. But he wouldn’t allow himself to go upstairs.

Not unless it had to be done.

He got in his car, started it, and drove down the hill to Jerusalem’s Lot.

Chapter Two

Susan (

I

)

He was sitting on a bench in the park when he observed the girl watching him. She was a very pretty girl, and there was a silk scarf tied over her light blond hair. She was currently reading a book, but there was a sketch pad and what looked like a charcoal pencil beside her. It was Tuesday, September 16, the first day of school, and the park had magically emptied of the rowdier element. What was left was a scattering of mothers with infants, a few old men sitting by the war memorial, and this girl sitting in the dappled shade of a gnarled old elm.

She looked up and saw him. An expression of startlement crossed her face. She looked down at her book; looked up at him again and started to rise; almost thought better of it; did rise; sat down again.

He got up and walked over, holding his own book, which was a paperback Western. “Hello,” he said agreeably. “Do we know each other?”

“No,” she said. “That is…you’re Benjaman Mears, right?”

“Right.” He raised his eyebrows.

She laughed nervously, not looking in his eyes except in a quick flash, to try to read the barometer of his intentions. She was quite obviously a girl not accustomed to speaking to strange men in the park.

“I thought I was seeing a ghost.” She held up the book in her lap. He saw fleetingly that “Jerusalem’s Lot Public Library” was stamped on the thickness of pages between covers. The book was Air Dance, his second novel. She showed him the photograph of himself on the back jacket, a photo that was four years old now. The face looked boyish and frighteningly serious—the eyes were black diamonds.

“Of such inconsequential beginnings dynasties are begun,” he said, and although it was a joking throwaway remark, it hung oddly in the air, like prophecy spoken in jest. Behind them, a number of toddlers were splashing happily in the wading pool and a mother was telling Roddy not to push his sister so high. The sister went soaring up on her swing regardless, dress flying, trying for the sky. It was a moment he remembered for years after, as though a special small slice had been cut from the cake of time. If nothing fires between two people, such an instant simply falls back into the general wrack of memory.

Then she laughed and offered him the book. “Will you autograph it?”

“A library book?”

“I’ll buy it from them and replace it.”

He found a mechanical pencil in his sweater pocket, opened the book to the flyleaf, and asked, “What’s your name?”

“Susan Norton.”

He wrote quickly, without thinking: For Susan Norton, the prettiest girl in the park. Warm regards, Ben Mears. He added the date below his signature in slashed notation.

“Now you’ll have to steal it,” he said, handing it back. “ Air Danceis out of print, alas.”

“I’ll get a copy from one of those book finders in New York.” She hesitated, and this time her glance at his eyes was a little longer. “It’s an awfully good book.”

“Thanks. When I take it down and look at it, I wonder how it ever got published.”

“Do you take it down often?”

“Yeah, but I’m trying to quit.”

She grinned at him and they both laughed and that made things more natural. Later he would have a chance to think how easily this had happened, how smoothly. The thought was never a comfortable one. It conjured up an image of fate, not blind at all but equipped with sentient 20/20 vision and intent on grinding helpless mortals between the great millstones of the universe to make some unknown bread.

“I read Conway’s Daughter, too. I loved that. I suppose you hear that all the time.”

“Remarkably little,” he said honestly. Miranda had also loved Conway’s Daughter, but most of his coffeehouse friends had been noncommittal and most of the critics had clobbered it. Well, that was critics for you. Plot was out, masturbation in.

“Well, I did.”

“Have you read the new one?”

“ Billy Said Keep Going? Not yet. Miss Coogan at the drugstore says it’s pretty racy.”

“Hell, it’s almost puritanical,” Ben said. “The language is rough, but when you’re writing about uneducated country boys, you can’t…look, can I buy you an ice-cream soda or something? I was just getting a hanker on for one.”

She checked his eyes a third time. Then smiled, warmly. “Sure. I’d love one. They’re great in Spencer’s.”

That was the beginning of it.

TWO

“Is that Miss Coogan?”

Ben asked it, low-voiced. He was looking at a tall, spare woman who was wearing a red nylon duster over her white uniform. Her blue-rinsed hair was done in a steplike succession of finger waves.

“That’s her. She’s got a little cart she takes to the library every Thursday night. She fills out reserve cards by the ton and drives Miss Starcher crazy.”

They were seated on red leather stools at the soda fountain. He was drinking a chocolate soda; hers was strawberry. Spencer’s also served as the local bus depot and from where they sat they could look through an old-fashioned scrolled arch and into the waiting room, where a solitary young man in Air Force blues sat glumly with his feet planted around his suitcase.

“Doesn’t look happy to be going wherever he’s going, does he?” she said, following his glance.

“Leave’s over, I imagine,” Ben said. Now, he thought, she’ll ask if I’ve ever been in the service.

But instead: “I’ll be on that ten-thirty bus one of these days. Goodby, ’salem’s Lot. Probably I’ll be looking just as glum as that boy.”

“Where?”

“New York, I guess. To see if I can’t finally become self-supporting.”

“What’s wrong with right here?”

“The Lot? I love it. But my folks, you know. They’d always be sort of looking over my shoulder. That’s a bummer. And the Lot doesn’t really have that much to offer the young career girl.” She shrugged and dipped her head to suck at her straw. Her neck was tanned, beautifully muscled. She was wearing a colorful print shift that hinted at a good figure.

“What kind of job are you looking for?”

She shrugged. “I’ve got a B.A. from Boston University…not worth the paper it’s printed on, really. Art major, English minor. The original dipso duo. Strictly eligible for the educated idiot category. I’m not even trained to decorate an office. Some of the girls I went to high school with are holding down plump secretarial jobs now. I never got beyond Personal Typing I, myself.”

“So what does that leave?”

“Oh…maybe a publishing house,” she said vaguely. “Or some magazine…advertising, maybe. Places like that can always use someone who can draw on command. I can do that. I have a portfolio.”

“Do you have offers?” he asked gently.

“No…no. But…”

“You don’t go to New York without offers,” he said. “Believe me. You’ll wear out the heels on your shoes.”

She smiled uneasily. “I guess you should know.”

“Have you sold stuff locally?”

“Oh yes.” She laughed abruptly. “My biggest sale to date was to the Cinex Corporation. They opened a new triple cinema in Portland and bought twelve paintings at a crack to hang in their lobby. Paid seven hundred dollars. I made a down payment on my little car.”

“You ought to take a hotel room for a week or so in New York,” he said, “and hit every magazine and publishing house you can find with your portfolio. Make your appointments six months in advance so the editors and personnel guys don’t have anything on their calendars. But for God’s sake, don’t just haul stakes for the big city.”

“What about you?” she asked, leaving off the straw and spooning ice cream. “What are you doing in the thriving community of Jerusalem’s Lot, Maine, population thirteen hundred?”

He shrugged. “Trying to write a novel.”

She was instantly alight with excitement. “In the Lot? What’s it about? Why here? Are you—”

He looked at her gravely. “You’re dripping.”

“I’m—? Oh, I am. Sorry.” She mopped the base of her glass with a napkin. “Say, I didn’t mean to pry. I’m really not gushy as a rule.”

“No apology needed,” he said. “All writers like to talk about their books. Sometimes when I’m lying in bed at night I make up a Playboyinterview about me. Waste of time. They only do authors if their books are big on campus.”

The Air Force youngster stood up. A Greyhound was pulling up to the curb out front, air brakes chuffing.

“I lived in ’salem’s Lot for four years as a kid. Out on the Burns Road.”

“The Burns Road? There’s nothing out there now but the Marshes and a little graveyard. Harmony Hill, they call it.”

“I lived with my Aunt Cindy. Cynthia Stowens. My dad died, see, and my mom went through a…well, kind of a nervous breakdown. So she farmed me out to Aunt Cindy while she got her act back together. Aunt Cindy put me on a bus back to Long Island and my mom just about a month after the big fire.” He looked at his face in the mirror behind the soda fountain. “I cried on the bus going away from Mom, and I cried on the bus going away from Aunt Cindy and Jerusalem’s Lot.”

“I was born the year of the fire,” Susan said. “The biggest damn thing that ever happened to this town and I slept through it.”

Ben laughed. “That makes you about seven years older than I thought in the park.”

“Really?” She looked pleased. “Thank you…I think. Your aunt’s house must have burned down.”

“Yes,” he said. “That night is one of my clearest memories. Some men with Indian pumps on their backs came to the door and said we’d have to leave. It was very exciting. Aunt Cindy dithered around, picking things up and loading them into her Hudson. Christ, what a night.”

“Was she insured?”

“No, but the house was rented and we got just about everything valuable into the car, except for the TV. We tried to lift it and couldn’t even budge it off the floor. It was a Video King with a seven-inch screen and a magnifying glass over the picture tube. Hell on the eyes. We only got one channel anyway—lots of country music, farm reports, and Kitty the Klown.”

“And you came back here to write a book,” she marveled.

Ben didn’t reply at once. Miss Coogan was opening cartons of cigarettes and filling the display rack by the cash register. The pharmacist, Mr Labree, was puttering around behind the high drug counter like a frosty ghost. The Air Force kid was standing by the door to the bus, waiting for the driver to come back from the bathroom.

“Yes,” Ben said. He turned and looked at her, full in the face, for the first time. She had a very pretty face, with candid blue eyes and a high, clear, tanned forehead. “Is this town your childhood?” he asked.

“Yes.”

He nodded. “Then you know. I was a kid in ’salem’s Lot and it’s haunted for me. When I came back, I almost drove right by because I was afraid it would be different.”

“Things don’t change here,” she said. “Not very much.”

“I used to play war with the Gardener kids down in the Marshes. Pirates out by Royal’s Pond. Capture-the-flag and hide-and-go-seek in the park. My mom and I knocked around some pretty hard places after I left Aunt Cindy. She killed herself when I was fourteen, but most of the magic dust had rubbed off me long before that. What there was of it was here. And it’s still here. The town hasn’t changed that much. Looking out on Jointner Avenue is like looking through a thin pane of ice—like the one you can pick off the top of the town cistern in November if you knock it around the edges first—looking through that at your childhood. It’s wavy and misty and in some places it trails off into nothing, but most of it is still all there.”

He stopped, amazed. He had made a speech.

“You talk just like your books,” she said, awed.

He laughed. “I never said anything like that before. Not out loud.”

“What did you do after your mother…after she died?”

“Knocked around,” he said briefly. “Eat your ice cream.”

She did.

“Some things have changed,” she said after a while. “Mr Spencer died. Do you remember him?”

“Sure. Every Thursday night Aunt Cindy came into town to do her shopping at Crossen’s store and she’d send me in here to have a root beer. That was when it was on draft, real Rochester root beer. She’d give me a handkerchief with a nickel wrapped up in it.”

“They were a dime when I came along. Do you remember what he always used to say?”

Ben hunched forward, twisted one hand into an arthritic claw, and turned one corner of his mouth down in a paralytic twist. “Your bladder,” he whispered. “Those rut beers will destroy your bladder, bucko.”

Her laughter pealed upward toward the slowly rotating fan over their heads. Miss Coogan looked up suspiciously. “That’s perfect!Except he used to call me lassie.”

They looked at each other, delighted.

“Say, would you like to go to a movie tonight?” he asked.

“I’d love to.”

“What’s closest?”

She giggled. “The Cinex in Portland, actually. Where the lobby is decorated with the deathless paintings of Susan Norton.”

“Where else? What kind of movies do you like?”

“Something exciting with a car chase in it.”

“Okay. Do you remember the Nordica? That was right here in town.”

“Sure. It closed in 1968. I used to go on double dates there when I was in high school. We threw popcorn boxes at the screen when the movies were bad.” She giggled. “They usually were.”

“They used to have those old Republic serials,” he said. “ Rocket Man. The Return of Rocket Man. Crash Callahan and the Voodoo Death God.”

“That was before my time.”

“Whatever happened to it?”

“That’s Larry Crockett’s real estate office now,” she said. “The drive-in over in Cumberland killed it, I guess. That and TV.”

They were silent for a moment, thinking their own thoughts. The Greyhound clock showed 10:45 am.

They said in chorus: “Say, do you remember—”

They looked at each other, and this time Miss Coogan looked up at both of them when the laughter rang out. Even Mr Labree looked over.

They talked for another fifteen minutes, until Susan told him reluctantly that she had errands to run but yes, she could be ready at seven-thirty. When they went different ways, they both marveled over the easy, natural, coincidental impingement of their lives.

Ben strolled back down Jointner Avenue, pausing at the corner of Brock Street to look casually up at the Marsten House. He remembered that the great forest fire of 1951 had burned almost to its very yard before the wind had changed.

He thought: Maybe it should have burned. Maybe that would have been better.

THREE

Nolly Gardener came out of the Municipal Building and sat down on the steps next to Parkins Gillespie just in time to see Ben and Susan walk into Spencer’s together. Parkins was smoking a Pall Mall and cleaning his yellowed fingernails with a pocketknife.

“That’s that writer fella, ain’t it?” Nolly asked.

“Yep.”

“Was that Susie Norton with him?”

“Yep.”

“Well, that’s interesting,” Nolly said, and hitched his garrison belt. His deputy star glittered importantly on his chest. He had sent away to a detective magazine to get it; the town did not provide its deputy constables with badges. Parkins had one, but he carried it in his wallet, something Nolly had never been able to understand. Of course everybody in the Lot knew he was the constable, but there was such a thing as tradition. There was such a thing as responsibility. When you were an officer of the law, you had to think about both. Nolly thought about them both often, although he could only afford to deputy part-time.

Parkins’s knife slipped and slit the cuticle of his thumb. “Shit,” he said mildly.

“You think he’s a real writer, Park?”

“Sure he is. He’s got three books right in this library.”

“True or made up?”

“Made up.” Parkins put his knife away and sighed.

“Floyd Tibbits ain’t going to like some guy makin’ time with his woman.”

“They ain’t married,” Parkins said. “And she’s over eighteen.”

“Floyd ain’t going to like it.”

“Floyd can crap in his hat and wear it backward for all of me,” Parkins said. He crushed his smoke on the step, took a Sucrets box out of his pocket, put the dead butt inside, and put the box back in his pocket.

“Where’s that writer fella livin’?”

“Down to Eva’s,” Parkins said. He examined his wounded cuticle closely. “He was up lookin’ at the Marsten House the other day. Funny expression on his face.”

“Funny? What do you mean?”

“Funny, that’s all.” Parkins took his cigarettes out. The sun felt warm and good on his face. “Then he went to see Larry Crockett. Wanted to lease the place.”

“The Marstenplace?”

“Yep.”

“What is he, crazy?”

“Could be.” Parkins brushed a fly from the left knee of his pants and watched it buzz away into the bright morning. “Ole Larry Crockett’s been a busy one lately. I hear he’s gone and sold the Village Washtub. Sold it a while back, as a matter of fact.”

“What, that old laundrymat?”

“Yep.”

“What would anyone want to put in there?”

“Dunno.”

“Well.” Nolly stood up and gave his belt another hitch. “Think I’ll take a turn around town.”

“You do that,” Parkins said, and lit another cigarette.

“Want to come?”

“No, I believe I’ll sit right here for a while.”

“Okay. See you.”

Nolly went down the steps, wondering (not for the first time) when Parkins would decide to retire so that he, Nolly, could have the job full-time. How in God’s name could you ferret out crime sitting on the Municipal Building steps?

Parkins watched him go with a mild feeling of relief. Nolly was a good boy, but he was awfully eager. He took out his pocketknife, opened it, and began paring his nails again.

FOUR

Jerusalem’s Lot was incorporated in 1765 (two hundred years later it had celebrated its bicentennial with fireworks and a pageant in the park; little Debbie Forester’s Indian princess costume was set on fire by a thrown sparkler and Parkins Gillespie had to throw six fellows in the local cooler for public intoxication), a full fifty-five years before Maine became a state as the result of the Missouri Compromise.

The town took its peculiar name from a fairly prosaic occurrence. One of the area’s earliest residents was a dour, gangling farmer named Charles Belknap Tanner. He kept pigs, and one of the large sows was named Jerusalem. Jerusalem broke out of her pen one day at feeding time, escaped into the nearby woods, and went wild and mean. Tanner warned small children off his property for years afterward by leaning over his gate and croaking at them in ominous, gore-crow tones: “Keep ’ee out o’ Jerusalem’s wood lot, if ’ee want to keep ’ee guts in ’ee belly!” The warning took hold, and so did the name. It proves little, except that perhaps in America even a pig can aspire to immortality.

The main street, known originally as the Portland Post Road, had been named after Elias Jointner in 1896. Jointner, a member of the House of Representatives for six years (up until his death, which was caused by syphilis, at the age of fifty-eight), was the closest thing to a personage that the Lot could boast—with the exception of Jerusalem the pig and Pearl Ann Butts, who ran off to New York City in 1907 to become a Ziegfeld girl.

Brock Street crossed Jointner Avenue dead center and at right angles, and the township itself was nearly circular (although a little flat on the east, where the boundary was the meandering Royal River). On a map, the two main roads gave the town an appearance very much like a telescopic sight.

The northwest quadrant of the sight was north Jerusalem, the most heavily wooded section of town. It was the high ground, although it would not have appeared very high to anyone except perhaps a Midwesterner. The tired old hills, which were honeycombed with old logging roads, sloped down gently toward the town itself, and the Marsten House stood on the last of these.

Much of the northeast quadrant was open land—hay, timothy, and alfalfa. The Royal River ran here, an old river that had cut its banks almost to the base level. It flowed under the small wooden Brock Street Bridge and wandered north in flat, shining arcs until it entered the land near the northern limits of the town, where solid granite lay close under the thin soil. Here it had cut fifty-foot stone cliffs over the course of a million years. The kids called it Drunk’s Leap, because a few years back Tommy Rathbun, Virge Rathbun’s tosspot brother, staggered over the edge while looking for a place to take a leak. The Royal fed the mill-polluted Androscoggin but had never been polluted itself; the only industry the Lot had ever boasted was a sawmill, long since closed. In the summer months, fishermen casting from the Brock Street Bridge were a common sight. A day when you couldn’t take your limit out of the Royal was a rare day.

The southeast quadrant was the prettiest. The land rose again, but there was no ugly blight of fire or any of the topsoil ruin that is a fire’s legacy. The land on both sides of the Griffen Road was owned by Charles Griffen, who was the biggest dairy farmer south of Mechanic Falls, and from Schoolyard Hill you could see Griffen’s huge barn with its aluminum roof glittering in the sun like a monstrous heliograph. There were other farms in the area, and a good many houses that had been bought by the white-collar workers who commuted to either Portland or Lewiston. Sometimes, in autumn, you could stand on top of Schoolyard Hill and smell the fragrant odor of the field burnings and see the toylike ’salem’s Lot Volunteer Fire Department truck, waiting to step in if anything got out of hand. The lesson of 1951 had remained with these people.

It was in the southwest area that the trailers had begun to move in, and everything that goes with them, like an exurban asteroid belt: junked-out cars up on blocks, tire swings hanging on frayed rope, glittering beer cans lying beside the roads, ragged wash hung on lines between makeshift poles, the ripe smell of sewage from hastily laid septic tanks. The houses in the Bend were kissing cousins to woodsheds, but a gleaming TV aerial sprouted from nearly every one, and most of the TVs inside were color, bought on credit from Grant’s or Sears. The yards of the shacks and trailers were usually full of kids, toys, pickup trucks, snowmobiles, and motorbikes. In some cases the trailers were well kept, but in most cases it seemed to be too much trouble. Dandelions and witch grass grew ankle-deep. Out near the town line, where Brock Street became Brock Road, there was Dell’s, where a rock ’n’ roll band played on Fridays and a c/w combo played on Saturdays. It had burned down once in 1971 and was rebuilt. For most of the down home cowboys and their girlfriends, it was the place to go and have a beer or a fight.

Most of the telephone lines were two-, four-, or six-party connections, and so folks always had someone to talk about. In all small towns, scandal is always simmering on the back burner, like your Aunt Cindy’s baked beans. The Bend produced most of the scandal, but every now and then someone with a little more status added something to the communal pot.

Town government was by town meeting, and while there had been talk ever since 1965 of changing to the town council form with biannual public budget hearings, the idea gained no way. The town was not growing fast enough to make the old way actively painful, although its stodgy, one-for-one democracy made some of the newcomers roll their eyes in exasperation. There were three selectmen, the town constable, an overseer of the poor, a town clerk (to register your car you had to go far out on the Taggart Stream Road and brave two mean dogs who ran loose in the yard), and the school commissioner. The volunteer Fire Department got a token appropriation of three hundred dollars each year, but it was mostly a social club for old fellows on pensions. They saw a fair amount of excitement during grass fire season and sat around the Reliable tall-taling each other the rest of the year. There was no Public Works Department because there were no public water lines, gas mains, sewage, or light-and-power. The CMP electricity pylons marched across town on a diagonal from northwest to southeast, cutting a huge gash through the timberland 150 feet wide. One of these stood close to the Marsten House, looming over it like an alien sentinel.

What ’salem’s Lot knew of wars and burnings and crises in government it got mostly from Walter Cronkite on TV. Oh, the Potter boy got killed in Vietnam and Claude Bowie’s son came back with a mechanical foot—stepped on a land mine—but he got a job with the post office helping Kenny Danles and so thatwas all right. The kids were wearing their hair longer and not combing it neatly like their fathers, but nobody really noticed anymore. When they threw the dress code out at the Consolidated High School, Aggie Corliss wrote a letter to the Cumberland Ledger, but Aggie had been writing to the Ledgerevery week for years, mostly about the evils of liquor and the wonder of accepting Jesus Christ into your heart as your personal savior.