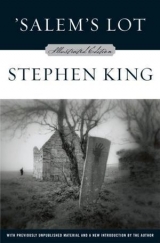

Текст книги "Salem's Lot"

Автор книги: Stephen Edwin King

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

He looked up at the Marsten House and spoke slowly.

“I think that house might be Hubert Marsten’s monument to evil, a kind of psychic sounding board. A supernatural beacon, if you like. Sitting there all these years, maybe holding the essence of Hubie’s evil in its old, moldering bones.

“And now it’s occupied again.

“And there’s been another disappearance.” He turned to her and cradled her upturned face in his hands. “You see, that’s something I never counted on when I came back here. I thought the house might have been torn down, but never in my wildest dreams that it had been bought. I saw myself renting it and…oh, I don’t know. Confronting my own terrors and evils, maybe. Playing ghost-breaker, maybe—be gone in the name of all the saints, Hubie. Or maybe just tapping into the atmosphere of the place to write a book scary enough to make me a million dollars. But no matter what, I felt that I was in control of the situation, and that would make all the difference. I wasn’t any nine-year-old kid anymore, ready to run screaming from a magic-lantern show that maybe came out of my own mind and no place else. But now…”

“Now what, Ben?”

“Now it’s occupied!” he burst out, and beat a fist into his palm. “I’m notin control of the situation. A little boy has disappeared and I don’t know what to make of it. It could have nothing to do with that house, but…I don’t believe it.” The last four words came out in measured lengths.

“Ghosts? Spirits?”

“Not necessarily. Maybe just some harmless guy who admired the house when he was a kid and bought it and became…possessed.”

“Do you know something about—” she began, alarmed.

“The new tenant? No. I’m just guessing. But if it is the house, I’d almost rather it was possession than something else.”

“What?”

He said simply, “Perhaps it’s called another evil man.”

FOUR

Ann Norton watched them from the window. She had called the drugstore earlier. No, Miss Coogan said, with something like glee. Not here. Haven’t been in.

Where have you been, Susan? Oh, where have you been?

Her mouth twisted down into a helpless ugly grimace.

Go away, Ben Mears. Go away and leave her alone.

FIVE

When she left his arms, she said, “Do something important for me, Ben.”

“Whatever I can.”

“Don’t mention those things to anyone else in town. Anyone.”

He smiled humorlessly. “Don’t worry. I’m not anxious to have people thinking I’ve been struck nuts.”

“Do you lock your room at Eva’s?”

“No.”

“I’d start locking it.” She looked at him levelly. “You have to think of yourself as under suspicion.”

“With you, too?”

“You would be, if I didn’t love you.”

And then she was gone, hastening up the driveway, leaving him to look after her, stunned by all he had said and more stunned by the four or five words she had said at the end.

SIX

He found when he got back to Eva’s that he could neither write nor sleep. He was too excited to do either. So he warmed up the Citroën, and after a moment of indecision, he drove out toward Dell’s place.

It was crowded, and the place was smoky and loud. The band, a country-and-western group on trial called the Rangers, was playing a version of “You’ve Never Been This Far Before,” which made up in volume for whatever it lost in quality. Perhaps forty couples were gyrating on the floor, most of them wearing blue jeans. Ben, a little amused, thought of Edward Albee’s line about monkey nipples.

The stools in front of the bar were held down by construction and mill workers, each drinking identical glasses of beer and all wearing nearly identical crepe-soled work boots, laced with rawhide.

Two or three barmaids with bouffant hairdos and their names written in gold thread on their white blouses (Jackie, Toni, Shirley) circulated to the tables and booths. Behind the bar, Dell was drawing beers, and at the far end, a hawklike man with his hair greased back was making mixed drinks. His face remained utterly blank as he measured liquor into shot glasses, dumped it into his silver shaker, and added whatever went with it.

Ben started toward the bar, skirting the dance floor, and someone called out, “Ben! Say, fella! How are you, buddy?”

Ben looked around and saw Weasel Craig sitting at a table close to the bar, a half-empty beer in front of him.

“Hello, Weasel,” Ben said, sitting down. He was relieved to see a familiar face, and he liked Weasel.

“Decided to get some night life, did you, buddy?” Weasel smiled and clapped him on the shoulder. Ben thought that his check must have come in; his breath alone could have made Milwaukee famous.

“Yeah,” Ben said. He got out a dollar and laid it on the table, which was covered with the circular ghosts of the many beer glasses that had stood there. “How you doing?”

“Just fine. What do you think of that new band? Great, ain’t they?”

“They’re okay,” Ben said. “Finish that thing up before it goes flat. I’m buying.”

“I been waitin’ to hear somebody say that all night. Jackie!” he bawled. “Bring my buddy here a pitcher! Budweiser!”

Jackie brought the pitcher on a tray littered with beer-soaked change and lifted it onto the table, her right arm bulging like a prizefighter’s. She looked at the dollar as if it were a new species of cockroach. “That’s a buck fawty,” she said.

Ben put another bill down. She picked them both up, fished sixty cents out of the assorted puddles on her tray, banged them down on the table, and said, “Weasel Craig, when you yell like that you sound like a rooster gettin’ its neck wrung.”

“You’re beautiful, darlin’,” Weasel said. “This is Ben Mears. He writes books.”

“Meetcha,” Jackie said, and disappeared into the dimness.

Ben poured himself a glass of beer and Weasel followed suit, filling his glass professionally to the top. The foam threatened to overspill and then backed down. “Here’s to you, buddy.”

Ben lifted his glass and drank.

“So how’s that writin’ goin’?”

“Pretty good, Weasel.”

“I seen you goin’ round with that little Norton girl. She’s a real peach, she is. You couldn’t do no better there.”

“Yes, she’s—”

“ Matt!” Weasel bawled, almost startling Ben into dropping his glass. By God, he thought, he doessound like a rooster saying good-by to this world.

“Matt Burke!” Weasel waved wildly, and a man with white hair raised his hand in greeting and started to cut through the crowd. “Here’s a fella you ought to meet,” Weasel told Ben. “Matt Burke’s one smart son of a whore.”

The man coming toward them looked about sixty. He was tall, wearing a clean flannel shirt open at the throat, and his hair, which was as white as Weasel’s, was cut in a flattop.

“Hello, Weasel,” he said.

“How are you, buddy?” Weasel said. “Want you to meet a fella stayin’ over to Eva’s. Ben Mears. Writes books, he does. He’s a lovely fella.” He looked at Ben. “Me’n Matt grew up together, only he got an education and I got the shaft.” Weasel cackled.

Ben stood up and shook Matt Burke’s bunched hand gingerly. “How are you?”

“Fine, thanks. I’ve read one of your books, Mr Mears. Air Dance.”

“Make it Ben, please. I hope you liked it.”

“I liked it much better than the critics, apparently,” Matt said, sitting down. “I think it will gain ground as time goes by. How are you, Weasel?”

“Perky,” Weasel said. “Just as perky as ever I could be. Jackie!” he bawled. “Bring Matt a glass!”

“Just wait a minute, y’old fart!” Jackie yelled back, drawing laughter from the nearby tables.

“She’s a lovely girl,” Weasel said. “Maureen Talbot’s girl.”

“Yes,” Matt said. “I had Jackie in school. Class of ’71. Her mother was ’51.”

“Matt teaches high school English,” Weasel told Ben. “You and him should have a lot to talk about.”

“I remember a girl named Maureen Talbot,” Ben said. “She came and got my aunt’s wash and brought it back all folded in a wicker basket. The basket only had one handle.”

“Are you from town, Ben?” Matt asked.

“I spent some time here as a boy. With my Aunt Cynthia.”

“Cindy Stowens?”

“Yes.”

Jackie came with a clean glass, and Matt tipped beer into it. “It really is a small world, then. Your aunt was in a senior class I taught my first year in ’salem’s Lot. Is she well?”

“She died in 1972.”

“I’m sorry.”

“She went very easily,” Ben said, and refilled his glass. The band had finished its set, and the members were trouping toward the bar. The level of conversation went down a notch.

“Have you come back to Jerusalem’s Lot to write a book about us?” Matt asked.

A warning bell went off in Ben’s mind.

“In a way, I suppose,” he said.

“This town could do much worse for a biographer. Air Dancewas a fine book. I think there might be another fine book in this town. I once thought I might write it.”

“Why didn’t you?”

Matt smiled—an easy smile with no trace of bitterness, cynicism, or malice. “I lacked one vital ingredient. Talent.”

“Don’t you believe it,” Weasel said, refilling his glass from the dregs of the pitcher. “Ole Matt’s got a world of talent. Schoolteachin’ is a wonnerful job. Nobody appreciates schoo’teachers, but they’re…” He swayed a little in his chair, searching for completion. He was becoming very drunk. “Salt of the earth,” he finished, took a mouthful of beer, grimaced, and stood up. “Pardon me while I take a leak.”

He wandered off, bumping into people and hailing them by name. They passed him on with impatience or good cheer, and watching his progress to the men’s room was like watching a pinball racket and bounce its way down toward the flipper buttons.

“There goes the wreck of a fine man,” Matt said, and held up one finger. A waitress appeared almost immediately and addressed him as Mr Burke. She seemed a trifle scandalized that her old English Classics teacher should be here, boozing it up with the likes of Weasel Craig. When she turned away to bring them another pitcher, Ben thought Matt looked a trifle bemused.

“I like Weasel,” Ben said. “I get a feeling there was a lot there once. What happened to him?”

“Oh, there’s no story there,” Matt said. “The bottle got him. It got him a little more each year and now it’s got all of him. He won a Silver Star at Anzio in World War II. A cynic might believe his life would have had more meaning if he had died there.”

“I’m not a cynic,” Ben said. “I like him still. But I think I better give him a ride home tonight.”

“That would be good of you. I come out here now and then to listen to the music. I like loud music. More than ever, since my hearing began to fail. I understand that you’re interested in the Marsten House. Is your book about it?”

Ben jumped. “Who told you that?”

Matt smiled. “How does that old Marvin Gaye song put it? I heard it through the grapevine. Luscious, vivid idiom, although the image is a bit obscure if you consider it. One conjures up a picture of a man standing with his ear cocked attentively toward a Concord or Tokay…I’m rambling. I ramble a great deal these days but rarely try to keep it in hand anymore. I heard from what the gentlemen of the press would call an informed source—Loretta Starcher, actually. She’s the librarian at our local citadel of literature. You’ve been in several times to look at the Cumberland Ledgerarticles pertaining to the ancient scandal, and she also got you two true-crime books that had articles on it. By the way, the Lubert one is good—he came to the Lot and researched it himself in 1946—but the Snow chapter is speculative trash.”

“I know,” Ben said automatically.

The waitress set down a fresh pitcher of beer and Ben suddenly had an uncomfortable image: Here is a fish swimming around comfortably and (he thinks) unobtrusively, flicking here and there amongst the kelp and the plankton. Draw away for the long view and there’s the kicker: It’s a goldfish bowl.

Matt paid the waitress and said, “Nasty thing that happened up there. It’s stayed in the town’s consciousness, too. Of course, tales of nastiness and murder are always handed down with slavering delight from generation to generation, while students groan and complain when they’re faced with a George Washington Carver or a Jonas Salk. But it’s more than that, I think. Perhaps it’s due to a geographical freak.”

“Yes,” Ben said, drawn in spite of himself. The teacher had just stated an idea that had been lurking below the level of his consciousness from the day he had arrived back in town, possibly even before that. “It stands on that hill overlooking the village like—oh, like some kind of dark idol.” He chuckled to make the remark seem trivial—it seemed to him that he had said something so deeply felt in an unguarded way that he must have opened a window on his soul to this stranger. Matt Burke’s sudden close scrutiny of him did not make him feel any better.

“That is talent,” he said.

“Pardon me?”

“You have said it precisely. The Marsten House has looked down on us all for almost fifty years, at all our little peccadilloes and sins and lies. Like an idol.”

“Maybe it’s seen the good, too,” Ben said.

“There’s little good in sedentary small towns. Mostly indifference spiced with an occasional vapid evil—or worse, a conscious one. I believe Thomas Wolfe wrote about seven pounds of literature about that.”

“I thought you weren’t a cynic.”

“You said that, not I.” Matt smiled and sipped at his beer. The band was moving away from the bar, resplendent in their red shirts and glittering vests and neckerchiefs. The lead singer took his guitar and began to chord it.

“At any rate, you never answered my question. Is your new book about the Marsten House?”

“I suppose it is, in a way.”

“I’m pumping you. Sorry.”

“It’s all right,” Ben said, thinking of Susan and feeling uncomfortable. “I wonder what’s keeping Weasel? He’s been gone a hell of a long time.”

“Could I presume on short acquaintanceship and ask a rather large favor? If you refuse, I’ll more than understand.”

“Sure, ask,” Ben said.

“I have a creative writing class,” Matt said. “They are intelligent children, eleventh-and twelfth-graders, most of them, and I would like to present someone who makes his living with words to them. Someone who—how shall I say?—has taken the word and made it flesh.”

“I’d be more than happy to,” Ben said, feeling absurdly flattered. “How long are your periods?”

“Fifty minutes.”

“Well, I don’t suppose I can bore them too badly in that length of time.”

“Oh? I do it quite well, I think,” Matt said. “Although I’m sure you wouldn’t bore them at all. This next week?”

“Sure. Name a day and a time.”

“Tuesday? Period four? That goes from eleven o’clock until ten of twelve. No one will boo you, but I suspect you will hear a great many stomachs rumble.”

“I’ll bring some cotton for my ears.”

Matt laughed. “I’m very pleased. I will meet you at the office, if that’s agreeable.”

“Fine. Do you—”

“Mr Burke?” It was Jackie, she of the heavy biceps. “Weasel’s passed out in the men’s room. Do you suppose—”

“Oh? Goodness, yes. Ben, would you—”

“Sure.”

They got up and crossed the room. The band had begun to play again, something about how the kids in Muskogee still respected the college dean.

The bathroom smelled of sour urine and chlorine. Weasel was propped against the wall between two urinals, and a fellow in an army uniform was pissing approximately two inches from his right ear.

His mouth was open and Ben thought how terribly old he looked, old and ravaged by cold, impersonal forces with no gentle touch in them. The reality of his own dissolution, advancing day by day, came home to him, not for the first time, but with shocking unexpectedness. The pity that welled up in his throat like clear, black waters was as much for himself as for Weasel.

“Here,” Matt said, “can you get an arm under him when this gentleman finishes relieving himself?”

“Yes,” Ben said. He looked at the man in the army uniform, who was shaking off in leisurely fashion. “Hurry it up, can you, buddy?”

“Why? He ain’t in no rush.”

Nevertheless, he zipped up and stepped away from the urinal so they could get in.

Ben got an arm around Weasel’s back, hooked a hand in his armpit, and lifted. For a moment his buttocks pressed against the tiled wall and he could feel the vibrations from the band. Weasel came up with the limp mail sack weight of utter unconsciousness. Matt slid his head under Weasel’s other arm, hooked his own arm around Weasel’s waist, and they carried him out the door.

“There goes Weasel,” someone said, and there was laughter.

“Dell ought to cut him off,” Matt said, sounding out of breath. “He knows how this always turns out.”

They went through the door into the foyer, and then out onto the wooden steps leading down to the parking lot.

“Easy,” Ben grunted. “Don’t drop him.”

They went down the stairs, Weasel’s limp feet clopping on the risers like blocks of wood.

“The Citroën…over in the last row.”

They carried him over. The coolness in the air was sharper now, and tomorrow the leaves would be blooded. Weasel had begun to grunt deep in his throat and his head jerked weakly on the stalk of his neck.

“Can you put him to bed when you get back to Eva’s?” Matt asked.

“Yes, I think so.”

“Good. Look, you can just see the rooftop of the Marsten House over the trees.”

Ben looked. Matt was right; the top angle just peeked above the dark horizon of pines, blotting out the stars at the rim of the visible world with the regular shape of human construction.

Ben opened the passenger door and said, “Here. Let me have him.”

He took Weasel’s full weight and slipped him neatly into the passenger seat and closed the door. Weasel’s head lolled against the window, giving it a flattened, grotesque look.

“Tuesday at eleven?”

“I’ll be there.”

“Thanks. And thanks for helping Weasel, too.” He held out his hand and Ben shook it.

He got in, started the Citroën, and headed back toward town. Once the roadhouse neon had disappeared behind the trees, the road was deserted and black, and Ben thought, These roads are haunted now.

Weasel gave a snort and a groan beside him and Ben jumped. The Citroën swerved minutely on the road.

Now, why did I think that?

No answer.

SEVEN

He opened the wing window so that it scooped cold air directly onto Weasel on the ride home, and by the time he drove into Eva Miller’s dooryard, Weasel had attained a soupy semiconsciousness.

Ben led him, half stumbling, up the back porch steps and into the kitchen, which was dimly lit by the stove’s fluorescent. Weasel moaned, then muttered deep in his throat, “She’s a lovely girl, Jack, and married women, they know…know…”

A shadow detached itself from the hall and it was Eva, huge in an old quilted housecoat, her hair done up in rollers and covered with a filmy net scarf. Her face was pale and ghostly with night cream.

“Ed,” she said. “Oh, Ed…you do go on, don’t you?”

His eyes opened a little at the sound of her voice, and a smile touched his features. “On and on and on,” he croaked. “Wouldn’t you know it more than the rest?”

“Can you get him up to his room?” she asked Ben.

“Yes, no sweat.”

He tightened his grip on Weasel and somehow got him up the stairs and down to his room. The door was unlocked and he carried him inside. The minute he laid him on the bed, signs of consciousness ceased and he fell into a deep sleep.

Ben paused a moment to look around. The room was clean, almost sterile, things put away with barrackslike neatness. As he began to work on Weasel’s shoes, Eva Miller said from behind him, “Never mind that, Mr Mears. Go on up, if you like.”

“But he ought to be—”

“I’ll undress him.” Her face was grave and full of dignified, measured sadness. “Undress him and give him an alcohol rub to help with his hangover in the morning. I’ve done it before. Many times.”

“All right,” Ben said, and went upstairs without looking back. He undressed slowly, thought about taking a shower, and decided not to. He got into bed and lay looking at the ceiling and did not sleep for a long time.

Chapter Six

The Lot (

II

)

Fall and spring came to Jerusalem’s Lot with the same suddenness of sunrise and sunset in the tropics. The line of demarcation could be as thin as one day. But spring is not the finest season in New England—it’s too short, too uncertain, too apt to turn savage on short notice. Even so, there are April days which linger in the memory even after one has forgotten the wife’s touch, or the feel of the baby’s toothless mouth at the nipple. But by mid-May, the sun rises out of the morning’s haze with authority and potency, and standing on your top step at seven in the morning with your dinner bucket in your hand, you know that the dew will be melted off the grass by eight and that the dust on the back roads will hang depthless and still in the air for five minutes after a car’s passage; and that by one in the afternoon it will be up to ninety-five on the third floor of the mill and the sweat will roll off your arms like oil and stick your shirt to your back in a widening patch and it might as well be July.

But when fall comes, kicking summer out on its treacherous ass as it always does one day sometime after the midpoint of September, it stays awhile like an old friend that you have missed. It settles in the way an old friend will settle into your favorite chair and take out his pipe and light it and then fill the afternoon with stories of places he has been and things he has done since last he saw you.

It stays on through October and, in rare years, on into November. Day after day the skies are a clear, hard blue, and the clouds that float across them, always west to east, are calm white ships with gray keels. The wind begins to blow by the day, and it is never still. It hurries you along as you walk the roads, crunching the leaves that have fallen in mad and variegated drifts. The wind makes you ache in some place that is deeper than your bones. It may be that it touches something old in the human soul, a chord of race memory that says Migrate or die—migrate or die. Even in your house, behind square walls, the wind beats against the wood and the glass and sends its fleshless pucker against the eaves and sooner or later you have to put down what you were doing and go out and see. And you can stand on your stoop or in your dooryard at mid-afternoon and watch the cloud shadows rush across Griffen’s pasture and up Schoolyard Hill, light and dark, light and dark, like the shutters of the gods being opened and closed. You can see the goldenrod, that most tenacious and pernicious and beauteous of all New England flora, bowing away from the wind like a great and silent congregation. And if there are no cars or planes, and if no one’s Uncle John is out in the wood lot west of town banging away at a quail or pheasant; if the only sound is the slow beat of your own heart, you can hear another sound, and that is the sound of life winding down to its cyclic close, waiting for the first winter snow to perform last rites.

TWO

That year the first day of fall (real fall as opposed to calendar fall) was September 28, the day that Danny Glick was buried in the Harmony Hill Cemetery.

Church services were private, but the graveside services were open to the town and a good portion of the town turned out—classmates, the curious, and the older people to whom funerals grow nearly compulsive as old age knits their shrouds up around them.

They came up Burns Road in a long line, twisting up and out of sight over the next hill. All the cars had their lights turned on in spite of the day’s brilliance. First came Carl Foreman’s hearse, its rear windows filled with flowers, then Tony Glick’s 1965 Mercury, its deteriorating muffler bellowing and farting. Behind that, in the next four cars, came relatives on both sides of the family, one bunch from as far away as Tulsa, Oklahoma. Others in that long, lights-on parade included: Mark Petrie (the boy Ralphie and Danny had been on their way to see the night Ralphie disappeared) and his mother and father; Richie Boddin and family; Mabel Werts in a car containing Mr and Mrs William Norton (sitting in the backseat with her cane planted between her swelled legs, she talked with unceasing constancy about other funerals she had attended all the way back to 1930); Lester Durham and his wife, Harriet; Paul Mayberry and his wife, Glynis; Pat Middler, Joe Crane, Vinnie Upshaw, and Clyde Corliss, all riding in a car driven by Milt Crossen (Milt had opened the beer cooler before they left, and they had all shared out a solemn six-pack in front of the stove); Eva Miller in a car which also contained her close friends Loretta Starcher and Rhoda Curless, who were both maiden ladies; Parkins Gillespie and his deputy, Nolly Gardener, riding in the Jerusalem’s Lot police car (Parkins’s Ford with a stick-on dashboard bubble); Lawrence Crockett and his sallow wife; Charles Rhodes, the sour bus driver, who went to all funerals on general principles; the Charles Griffen family, including wife and two sons, Hal and Jack, the only offspring still living at home.

Mike Ryerson and Royal Snow had dug the grave early that morning, laying strips of fake grass over the raw soil they had thrown out of the ground. Mike had lighted the Flame of Remembrance that the Glicks had specified. Mike could remember thinking that Royal didn’t seem himself this morning. He was usually full of little jokes and ditties about the work at hand (cracked, off-key tenor: “They wrap you up in a big white sheet, an’ put you down at least six feet….”), but this morning he had seemed exceptionally quiet, almost sullen. Hung over, maybe, Mike thought. He and that muscle-bound buddy of his, Peters, had certainly been slopping it up down at Dell’s the night before.

Five minutes ago, when he had seen Carl’s hearse coming over the hill about a mile down the road, he had swung open the wide iron gates, glancing up at the high iron spikes as he always did since he had found Doc up there. With the gates open, he walked back to the newly dug grave where Father Donald Callahan, the pastor of the Jerusalem’s Lot parish, waited by the grave. He was wearing a stole about his shoulders and the book he held was open to the children’s burial service. This was what they called the third station, Mike knew. The first was the house of the deceased, the second at the tiny Catholic Church, St Andrew’s. Last station, Harmony Hill. Everybody out.

A little chill touched him and he looked down at the bright plastic grass, wondering why it had to be a part of every funeral. It looked like exactly what it was: a cheap imitation of life discreetly masking the heavy brown clods of the final earth.

“They’re on their way, Father,” he said.

Callahan was a tall man with piercing blue eyes and a ruddy complexion. His hair was a graying steel color. Ryerson, who hadn’t been to church since he turned sixteen, liked him the best of all the local witch doctors. John Groggins, the Methodist minister, was a hypocritical old poop, and Patterson, from the Church of the Latter-day Saints and Followers of the Cross, was as crazy as a bear stuck in a honey tree. At a funeral for one of the church deacons two or three years back, Patterson had gotten right down and rolled on the ground. But Callahan seemed nice enough for a Pope-lover; his funerals were calm and comforting and always short. Ryerson doubted if Callahan had gotten all those red and broken veins in his cheeks and around his nose from praying, but if Callahan did a little drinking, who was to blame him? The way the world was, it was a wonder all those preachers didn’t end up in looney bins.

“Thanks, Mike,” he said, and looked up at the bright sky. “This is going to be a hard one.”

“I guess so. How long?”

“Ten minutes, no more. I’m not going to draw out his parents’ agony. There’s enough of that still ahead of them.”

“Okay,” Mike said, and walked toward the rear of the graveyard. He would jump over the stone wall, go into the woods, and eat a late lunch. He knew from long experience that the last thing the grieving family and friends want to see during the third station is the resident gravedigger in his dirt-stained coveralls; it kind of put a crimp in the minister’s glowing pictures of immortality and the pearly gates.

Near the back wall he paused and bent to examine a slate headstone that had fallen forward. He stood it up and again felt a small chill go through him as he brushed the dirt from the inscription:

HUBERT BARCLAY MARSTEN

October 6, 1889

August 12, 1939

The angel of Death who holdeth

The bronze Lamp beyond the golden door

Hath taken thee into dark Waters

And below that, almost obliterated by thirty-six seasons of freeze and thaw:

God Grant He Lie Still

Still vaguely troubled and still not knowing why, Mike Ryerson went back into the woods to sit by the brook and eat his lunch.

THREE

In the early days at the seminary, a friend of Father Callahan’s had given him a blasphemous crewelwork sampler which had sent him into gales of horrified laughter at the time, but which seemed more true and less blasphemous as the years passed: God grant me the SERENITY to accept what I cannot change, the TENACITY to change what I may, and the GOOD LUCK not to fuck up too often.This in Old English script with a rising sun in the background.

Now, standing before Danny Glick’s mourners, that old credo recurred.

The pallbearers, two uncles and two cousins of the dead boy, had lowered the coffin into the ground. Marjorie Glick, dressed in a black coat and a veiled black hat, her face showing through the mesh in the netting like cottage cheese, stood swaying in the protective curve of her father’s arm, clutching a black purse as though it were a life preserver. Tony Glick stood apart from her, his face shocked and wandering. Several times during the church service he had looked around, as if to verify his presence among these people. His face was that of a man who believes he is dreaming.

The church can’t stop this dream, Callahan thought. Nor all the serenity, tenacity, or good luck in the world. The fuck-up has already happened.

He sprinkled holy water on the coffin and the grave, sanctifying them for all time.

“Let us pray,” he said. The words rolled melodiously from his throat as they always had, in shine and shadow, drunk or sober. The mourners bowed their heads.