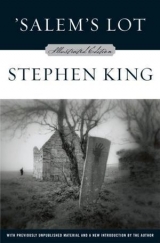

Текст книги "Salem's Lot"

Автор книги: Stephen Edwin King

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

“Wind her, Franklin!” Virgil cried, and let out a massive belch as the pickup crashed through the gate, knocking it onto the can-littered verge of the road. Franklin shifted into second and shot up the rutted, chuck-holed road. The truck bounced madly on its worn springs. Bottles fell off the back end and smashed. Seagulls took to the air in screaming, circling waves.

A quarter of a mile beyond the gate, the Burns Road fork (now known as the Dump Road) ended in a widening clearing that was the dump. The close-pressing alders and maples gave way to reveal a great flat area of raw earth which had been scored and runneled by the constant use of the old Case bulldozer which was now parked by Dud’s shack. Beyond this flat area was the gravel pit where current dumping went on. The trash and garbage, glitter-shot with bottles and aluminum cans, stretched away in gigantic dunes.

“Goddamn no-account hunchbacked pisswah, looks like he ain’t plowed nor burned all the week long,” Franklin said. He jammed both feet on the brake pedal, which sank all the way to the floor with a mechanical scream. After a while the truck stopped. “He’s laid up with a case, that’s what.”

“I never knew Dud to drink much,” Virgil said, tossing his empty out the window and pulling another from the brown bag on the floor. He opened it on the door latch, and the beer, crazied up from the bumps, bubbled out over his hand.

“All them hunchbacks do,” Franklin said wisely. He spat out the window, discovered it was closed, and swiped his shirtsleeve across the scratched and cloudy glass. “We’ll go see him. Might be somethin’ in it.”

He backed the truck around in a huge, wandering circle and pulled up with the tailgate hanging over the latest accumulation of the Lot’s accumulated throwaway. He switched off the ignition, and silence pressed in on them suddenly. Except for the restless calling of the gulls, it was complete.

“Ain’t it quiet,” Virgil muttered.

They got out of the truck and went around to the back. Franklin unhooked the S-bolts that held the tailgate and let it drop with a crash. The gulls that had been feeding at the far end of the dump rose in a cloud, squalling and scolding.

The two of them climbed up without a word and began heaving the Crappie off the end. Green plastic bags spun through the clear air and smashed open as they hit. It was an old job for them. They were a part of the town that few tourists ever saw (or cared to)—firstly, because the town ignored them by tacit agreement, and secondly, because they had developed their own protective coloration. If you met Franklin’s pickup on the road, you forgot it the instant it was gone from your rearview mirror. If you happened to see their shack with its tin chimney sending a pencil line of smoke into the white November sky, you overlooked it. If you met Virgil coming out of the Cumberland greenfront with a bottle of welfare vodka in a brown bag, you said hi and then couldn’t quite remember who it was you had spoken to; the face was familiar but the name just slipped your mind. Franklin’s brother was Derek Boddin, father of Richie (lately deposed king of Stanley Street Elementary School), and Derek had nearly forgotten that Franklin was still alive and in town. He had progressed beyond black sheepdom; he was totally gray.

Now, with the truck empty, Franklin kicked out a last can– clink!—and hitched up his green work pants. “Let’s go see Dud,” he said.

They climbed down from the truck and Virgil tripped over one of his own rawhide lacings and sat down hard. “Christ, they don’t make these things half-right,” he muttered obscurely.

They walked across to Dud’s tarpaper shack. The door was closed.

“Dud!” Franklin bawled. “Hey, Dud Rogers!” He thumped the door once, and the whole shack trembled. The small hook-and-eye lock on the inside of the door snapped off, and the door tottered open. The shack was empty but filled with a sickish-sweet odor that made them look at each other and grimace—and they were barroom veterans of a great many fungoid smells. It reminded Franklin fleetingly of pickles that had lain in a dark crock for many years, until the fluid seeping out of them had turned white.

“Son of a whore,” Virgil said. “Worse than gangrene.”

Yet the shack was astringently neat. Dud’s extra shirt was hung on a hook over the bed, the splintery kitchen chair was pushed up to the table, and the cot was made up Army-style. The can of red paint, with fresh drips down the sides, was placed on a fold of newspaper behind the door.

“I’m about to puke if we don’t get out of here,” Virgil said. His face had gone a whitish-green.

Franklin, who felt no better, backed out and shut the door.

They surveyed the dump, which was as deserted and sterile as the mountains of the moon.

“He ain’t here,” Franklin said. “He’s back in the woods someplace, laying up snookered.”

“Frank?”

“What,” Franklin said shortly. He was out of temper.

“That door was latched on the inside. If he ain’t there, how did he get out?”

Startled, Franklin turned around and regarded the shack. Through the window, he started to say, and then didn’t. The window was nothing but a square cut into the tarpaper and buttoned up with all-weather plastic. The window wasn’t large enough for Dud to squirm through, not with the hump on his back.

“Never mind,” Franklin said gruffly. “If he don’t want to share, fuck him. Let’s get out of here.”

They walked back to the truck, and Franklin felt something seeping through the protective membrane of drunkenness—something he would not remember later, or want to: a creeping feeling; a feeling that something here had gone terribly awry. It was as if the dump had gained a heartbeat and that beat was slow yet full of terrible vitality. He suddenly wanted to go away very quickly.

“I don’t see any rats,” Virgil said suddenly.

And there were none to be seen; only the gulls. Franklin tried to remember a time when he had brought the Crappie to the dump and seen no rats. He couldn’t. And he didn’t like that, either.

“He must have put out poison bait, huh, Frank?”

“Come on, let’s go,” Franklin said. “Let’s get the hell out of here.”

SEVEN

After supper, they let Ben go up and see Matt Burke. It was a short visit; Matt was sleeping. The oxygen tent had been taken away, however, and the head nurse told Ben that Matt would almost certainly be awake tomorrow morning and able to see visitors for a short time.

Ben thought his face looked drawn and cruelly aged, for the first time an old man’s face. Lying still, with the loosened flesh of his neck rising out of the hospital johnny, he seemed vulnerable and defenseless. If it’s all true, Ben thought, these people are doing you no favors, Matt. If it’s all true, then we’re in the citadel of unbelief, where nightmares are dispatched with Lysol and scalpels and chemotherapy rather than with stakes and Bibles and wild mountain thyme. They’re happy with their life support units and hypos and enema bags filled with barium solution. If the column of truth has a hole in it, they neither know nor care.

He walked to the head of the bed and turned Matt’s head with gentle fingers. There were no marks on the skin of his neck; the flesh was blameless.

He hesitated a moment longer, then went to the closet and opened it. Matt’s clothes hung there, and hooked over the closet door’s inside knob was the crucifix he had been wearing when Susan visited him. It hung from a filigreed chain that gleamed softly in the room’s subdued light.

Ben took it back to the bed and put it around Matt’s neck.

“Here, what are you doing?”

A nurse had come in with a pitcher of water and a bedpan with a towel spread decorously over the opening.

“I’m putting his cross around his neck,” Ben said.

“Is he a Catholic?”

“He is now,” Ben said somberly.

EIGHT

Night had fallen when a soft rap came at the kitchen door of the Sawyer house on the Deep Cut Road. Bonnie Sawyer, with a small smile on her lips, went to answer it. She was wearing a short ruffled apron tied at the waist, high heels, and nothing else.

When she opened the door, Corey Bryant’s eyes widened and his mouth dropped open. “Buh,” he said. “Buh…Buh…Bonnie?”

“What’s the matter, Corey?” She put a hand on the doorjamb with light deliberation, pulling her bare breasts up to their sauciest angle. At the same time she crossed her feet demurely, modeling her legs for him.

“Jeez, Bonnie, what if it had been—”

“The man from the telephone company?” she asked, and giggled. She took one of his hands and placed it on the firm flesh of her right breast. “Want to read my meter?”

With a grunt that held a note of desperation (the drowning man going down for the third time, clutching a mammary instead of a straw), he pulled her to him. His hands cupped her buttocks, and the starched apron crackled briskly between them.

“Oh my,” she said, wiggling against him. “Are you going to test my receiver, Mr Telephone Man? I’ve been waiting for an important call all day—”

He picked her up and kicked the door shut behind him. She did not need to direct him to the bedroom. He knew his way.

“You’re sure he’s not going to be home?” he asked.

Her eyes gleamed in the darkness. “Why, who can you mean, Mr Telephone Man? Not my handsome hubby…he’s in Burlington, Vermont.”

He put her down on the bed crossways, with her legs dangling off the side.

“Turn on the light,” she said, her voice suddenly slow and heavy. “I want to see what you’re doing.”

He turned on the bedside lamp and looked down at her. The apron had been pulled away to one side. Her eyes were heavy-lidded and warm, the pupils large and brilliant.

“Take that thing off,” he said, gesturing.

“You take it off,” she said. “You can figure out the knots, Mr Telephone Man.”

He bent to do it. She always made him feel like a dry-mouth kid stepping up to the plate for the first time, and his hands always trembled when they got near her, as if her very flesh was transmitting a strong current into the air all around her. She never left his mind completely anymore. She was lodged in there like a sore inside the cheek which the tongue keeps poking and testing. She even cavorted through his dreams, golden-skinned, blackly exciting. Her invention knew no bounds.

“No, on your knees,” she said. “Get on your knees for me.”

He dropped clumsily onto his knees and crawled toward her, reaching for the apron ties. She put one high-heeled foot on each shoulder. He bent to kiss the inside of her thigh, the flesh firm and slightly warm under his lips.

“That’s right, Corey, that’s just right, keep going up, keep—”

“Well, this is cute, ain’t it?”

Bonnie Sawyer screamed.

Corey Bryant looked up, blinking and confused.

Reggie Sawyer was leaning in the bedroom doorway. He was holding a shotgun cradled loosely over his forearm, barrels pointed at the floor.

Corey felt a warm gush as his bladder let go.

“So it’s true,” Reggie marveled. He stepped into the room. He was smiling. “How about that? I owe that tosspot Mickey Sylvester a case of Budweiser. Goddamn.”

Bonnie found her voice first.

“Reggie, listen. It isn’t what you think. He broke in, he was like a crazy-man, he, he was—”

“Shut up, cunt.” He was still smiling. It was a gentle smile. He was quite big. He was wearing the same steel-colored suit he had been wearing when she had kissed him good-by two hours before.

“Listen,” Corey said weakly. His mouth felt full of loose spit. “Please. Please don’t kill me. Not even if I deserve it. You don’t want to go to jail. Not over this. Beat me up, I got that coming, but please don’t—”

“Get up off your knees, Perry Mason,” Reggie Sawyer said, still smiling his gentle smile. “Your fly’s unzipped.”

“Listen, Mr Sawyer—”

“Oh, call me Reggie,” Reggie said, smiling gently. “We’re almost best buddies. I’ve even been getting your sloppy seconds, isn’t that right?”

“Reggie, this isn’t what you think, he raped me—”

Reggie looked at her and his smile was gentle and benign. “If you say another word, I’m going to jam this up inside you and let you have some special airmail.”

Bonnie began to moan. Her face had gone the color of unflavored yogurt.

“Mr Sawyer…Reggie…”

“Your name’s Bryant, ain’t it? Your daddy’s Pete Bryant, ain’t he?”

Corey’s head bobbed madly in agreement. “Yeah, that’s right. That’s just right. Listen—”

“I used to sell him number two fuel oil when I was driving for Jim Webber,” Reggie said, smiling with gentle reminiscence. “That was four or five years before I met this high-box bitch here. Your daddy know you’re here?”

“No, sir, it’d break his heart. You can beat me up, I got that coming, but if you kill me my daddy’d find out and I bet it’d kill him dead as shit and then you’d be responsible for two—”

“No, I bet he don’t know. Come on out in the living room a minute. We got to talk this over. Come on.” He smiled gently at Corey to show him that he meant him no harm and then his eyes flicked to Bonnie, who was staring at him with bulging eyes. “You stay right there, puss, or you ain’t never going to know how Secret Stormcomes out. Come on, Bryant.” He gestured with the shotgun.

Corey walked out into the living room ahead of Reggie, staggering a little. His legs were rubber. A patch between his shoulder blades began to itch insanely. That’s where he’s going to put it, he thought, right between the shoulder blades. I wonder if I’ll live long enough to see my guts hit the wall—

“Turn around,” Reggie said.

Corey turned around. He was beginning to blubber. He didn’t want to blubber, but he couldn’t seem to help it. He supposed it didn’t matter if he blubbered or not. He had already wet himself.

The shotgun was no longer dangling casually over Reggie’s forearm. The double barrels were pointing directly at Corey’s face. The twin bores seemed to swell and yawn until they were bottomless wells.

“You know what you been doin’?” Reggie asked. The smile was gone. His face was very grave.

Corey didn’t answer. It was a stupid question. He did keep on blubbering, however.

“You slept with another guy’s wife, Corey. That your name?”

Corey nodded, tears streaming down his cheeks.

“You know what happens to guys like that if they get caught?”

Corey nodded.

“Grab the barrel of this shotgun, Corey. Very easy. It’s got a five-pound pull and I got about three on it now. So pretend…oh, pretend you’re grabbing my wife’s tit.”

Corey reached out one shaking hand and placed it on the barrel of the shotgun. The metal was cool against his flushed palm. A long, agonized groan came out of his throat. Nothing else was left. Pleading was done.

“Put it in your mouth, Corey. Both barrels. Yes, that’s right. Easy!…that’s okay. Yes, your mouth’s big enough. Slip it right in there. You know all about slipping it in, don’t you?”

Corey’s jaws were open to their widest accommodation. The barrels of the shotgun were pushed back nearly to his palate, and his terrified stomach was trying to retch. The steel was oily against his teeth.

“Close your eyes, Corey.”

Corey only stared at him, his swimming eyes as big as tea saucers.

Reggie smiled his gentle smile again. “Close those baby blue eyes, Corey.”

Corey closed them.

His sphincter let go. He was only dimly aware of it.

Reggie pulled both triggers. The hammers fell on empty chambers with a double click-click.

Corey fell onto the floor in a dead faint.

Reggie looked down at him for a moment, smiling gently, and then reversed the shotgun so the butt end was up. He turned to the bedroom.

“Here I come, Bonnie. Ready or not.”

Bonnie Sawyer began to scream.

NINE

Corey Bryant was stumbling up the Deep Cut Road toward where he had left his phone truck parked. He stank. His eyes were bloodshot and glassy. There was a large bump on the back of his head where he had struck it on the floor when he fainted. His boots made dragging, scuffing sounds on the soft shoulder. He tried to think about the scuffing sounds and nothing else, most notably about the sudden and utter ruin of his life. It was quarter past eight.

Reggie Sawyer had still been smiling gently when he ushered Corey out the kitchen door. Bonnie’s steady, racking sobs had come from the bedroom, counterpointing his words. “You go on up the road like a good boy, now. Get in your truck and go back to town. There’s a bus that comes in from Lewiston for Boston at quarter to ten. From Boston you can get a bus to anywhere in the country. That bus stops at Spencer’s. You be on it. Because if I ever see you again, I’m going to kill you. She’ll be all right now. She’s broke in now. She’s gonna have to wear pants and long-sleeve blouses for a couple of weeks, but I didn’t mark her face. You just want to get out of ’salem’s Lot before you clean yourself up and start thinking you are a man again.”

And now here he was, walking up this road, about to do just what Reggie Sawyer said. He could go south from Boston…somewhere. He had a little over a thousand dollars saved in the bank. His mother had always said he was a very saving soul. He could wire for the money, live on it until he could get a job and begin the years-long job of forgetting this night—the taste of the gun barrel, the smell of his own shit satcheled in his trousers.

“Hello, Mr Bryant.”

Corey gave a stifled scream and stared wildly into the dark, at first seeing nothing. The wind was moving in the trees, making shadows jump and dance across the road. Suddenly his eyes made out a more solid shadow, standing by the stone wall that ran between the road and Carl Smith’s back pasture. The shadow had a manlike form, but there was something…something…

“Who are you?”

“A friend who sees much, Mr Bryant.”

The form shifted and came from the shadows. In the faint light, Corey saw a middle-aged man with a black mustache and deep, bright eyes.

“You’ve been ill used, Mr Bryant.”

“How do you know my business?”

“I know a great deal. It’s my business to know. Smoke?”

“Thanks.” He took the offered cigarette gratefully. He put it between his lips. The stranger struck a light, and in the glow of the wooden match he saw that the stranger’s cheekbones were high and Slavic, his forehead pale and bony, his dark hair swept straight back. Then the light was gone and Corey was dragging harsh smoke into his lungs. It was a dago cigarette, but any cigarette was better than none. He began to feel a little calmer.

“Who are you?” he asked again.

The stranger laughed, a startlingly rich and full-bodied sound that drifted off on the slight breeze like the smoke of Corey’s cigarette.

“Names!” he said. “Oh, the American insistence on names! Let me sell you an auto because I am Bill Smith! Eat at this one! Watch that one on television! My name is Barlow, if that eases you.” And he burst into laughter again, his eyes twinkling and shining. Corey felt a smile creep onto his own lips and could scarcely believe it. His troubles seemed distant, unimportant, in comparison to the derisive good humor in those dark eyes.

“You’re a foreigner, aren’t you?” Corey asked.

“I am from many lands; but to me this country…this town…seems full of foreigners. You see? Eh? Eh?” He burst into that full-throated crow of laughter again, and this time Corey found himself joining in. The laughter escaped his throat under full pressure, rising a bit with delayed hysteria.

“Foreigners, yes,” he resumed, “but beautiful, enticing foreigners, bursting with vitality, full-blooded and full of life. Do you know how beautiful the people of your country and your town are, Mr Bryant?”

Corey only chuckled, slightly embarrassed. He did not look away from the stranger’s face, however. It held him rapt.

“They have never known hunger or want, the people of this country. It has been two generations since they knew anything close to it, and even then it was like a voice in a distant room. They think they have known sadness, but their sadness is that of a child who has spilled his ice cream on the grass at a birthday party. There is no…how is the English?…attenuation in them. They spill each other’s blood with great vigor. Do you believe it? Do you see?”

“Yes,” Corey said. Looking into the stranger’s eyes, he could see a great many things, all of them wonderful.

“The country is an amazing paradox. In other lands, when a man eats to his fullest day after day, that man becomes fat…sleepy…piggish. But in this land…it seems the more you have the more aggressive you become. You see? Like Mr Sawyer. With so much; yet he begrudges you a few crumbs from his table. Also like a child at a birthday party, who will push away another baby even though he himself can eat no more. Is it not so?”

“Yes,” Corey said. Barlow’s eyes were so large, and so understanding. It was all a matter of—

“It is all a matter of perspective, is it not?”

“Yes!” Corey exclaimed. The man had put his finger on the right, the exact, the perfect, word. The cigarette dropped unnoticed from his fingers and lay smoldering on the road.

“I might have bypassed such a rustic community as this,” the stranger said reflectively. “I might have gone to one of your great and teeming cities. Bah!” He drew himself up suddenly, and his eyes flashed. “What do I know of cities? I should be run over by a hansom crossing the street! I should choke on nasty air! I should come in contact with sleek, stupid dilettantes whose concerns are…what do you say? inimical?…yes, inimical to me. How should a poor rustic like myself deal with the hollow sophistication of a great city…even an American city? No! And no and no! I spiton your cities!”

“Oh yes!” Corey whispered.

“So I have come here, to a town which was first told of to me by a most brilliant man, a former townsman himself, now lamentably deceased. The folk here are still rich and full-blooded, folk who are stuffed with the aggression and darkness so necessary to…there is no English for it. Pokol; vurderlak; eyalik. Do you follow?”

“Yes,” Corey whispered.

“The people have not cut off the vitality which flows from their mother, the earth, with a shell of concrete and cement. Their hands are plunged into the very waters of life. They have ripped the life from the earth, whole and beating! Is it not true?”

“Yes!”

The stranger chuckled kindly and put a hand on Corey’s shoulder. “You are a good boy. A fine, strong boy. I don’t think you want to leave this so-perfect town, do you?”

“No…” Corey whispered, but he was suddenly doubtful. Fear was returning. But surely it was unimportant. This man would allow no harm to come to him.

“And so you shall not. Ever again.”

Corey stood trembling, rooted to the spot, as Barlow’s head inclined toward him.

“And you shall yet have your vengeance on those who would fill themselves while others want.”

Corey Bryant sank into a great forgetful river, and that river was time, and its waters were red.

TEN

It was nine o’clock and the Saturday night movie was coming on the hospital TV bolted to the wall when the phone beside Ben’s bed rang. It was Susan, and her voice was barely under control.

“Ben, Floyd Tibbits is dead. He died in his cell some time last night. Dr Cody says acute anemia—but I wentwith Floyd! He had high blood pressure. That’s why the Army wouldn’t take him!”

“Slow down,” Ben said, sitting up.

“There’s more. A family named McDougall out in the Bend. A little ten-month-old baby died out there. They took Mrs McDougall away in restraints.”

“Have you heard how the baby died?”

“My mother said Mrs Evans came over when she heard Sandra McDougall screaming, and Mrs Evans called old Dr Plowman. Plowman didn’t say anything, but Mrs Evans told my mother that she couldn’t see a thing wrong with the baby…except it was dead.”

“And both Matt and I, the crackpots, just happen to be out of town and out of action,” Ben said, more to himself than to Susan. “Almost as if it were planned.”

“There’s more.”

“What?”

“Carl Foreman is missing. And so is the body of Mike Ryerson.”

“I think that’s it,” he heard himself saying. “That has to be it. I’m getting out of here tomorrow.”

“Will they let you go so soon?”

“They aren’t going to have anything to say about it.” He spoke the words absently; his mind had already moved on to another subject. “Have you got a crucifix?”

“Me?” She sounded startled and a little amused. “Gosh, no.”

“I’m not joking with you, Susan—I was never more serious. Is there anyplace where you can get one at this hour?”

“Well, there’s Marie Boddin. I could walk—”

“No. Stay off the streets. Stay in the house. Make one yourself, even if it only means gluing two sticks together. Leave it by your bed.”

“Ben, I still don’t believe this. A maniac, maybe, someone who thinkshe’s a vampire, but—”

“Believe what you want, but make the cross.”

“But—”

“Will you do it? Even if it only means humoring me?”

Reluctantly: “Yes, Ben.”

“Can you come to the hospital tomorrow around nine?”

“Yes.”

“Okay. We’ll go upstairs and fill in Matt together. Then you and I are going to talk to Dr James Cody.”

She said, “He’s going to think you’re crazy, Ben. Don’t you know that?”

“I suppose I do. But it all seems more real after dark, doesn’t it?”

“Yes,” she said softly. “God, yes.”

For no reason at all he thought of Miranda and Miranda’s dying: the motorcycle hitting the wet patch, going into a skid, the sound of her scream, his own brute panic, and the side of the truck growing and growing as they approached it broadside.

“Susan?”

“Yes.”

“Take good care of yourself. Please.”

After she hung up, he put the phone back in the cradle and stared at the TV, barely seeing the Doris Day-Rock Hudson comedy that had begun to unreel up there. He felt naked, exposed. He had no cross himself. His eyes strayed to the windows, which showed only blackness. The old, childlike terror of the dark began to creep over him and he looked at the television where Doris Day was giving a shaggy dog a bubble bath and was afraid.

ELEVEN

The county morgue in Portland is a cold and antiseptic room done entirely in green tile. The floors and walls are a uniform medium green, and the ceiling is a lighter green. The walls are lined with square doors which look like large bus-terminal coin lockers. Long parallel fluorescent tubes shed a chilly neutral light over all of this. The decor is hardly inspired, but none of the clientele have ever been known to complain.

At quarter to ten on this Saturday night, two attendants were wheeling in the sheet-covered body of a young homosexual who had been shot in a downtown bar. It was the first stiff they had received that night; the highway fatals usually came in between 1:00 and 3:00 am.

Buddy Bascomb was in the middle of a Frenchman joke that had to do with vaginal deodorant spray when he broke off in midsentence and stared down the line of locker doors M-Z. Two of them were standing open.

He and Bob Greenberg left the new arrival and hurried down quickly. Buddy glanced at the tag on the first door he came to while Bob went down to the next.

TIBBITS, FLOYD MARTIN

Sex: M

Admitted: 10/4/75

Autops. sched.: 10/5/75

Signator: J.M. Cody, M.D.

He yanked the handle set inside the door, and the slab rolled out on silent casters.

Empty.

“Hey!” Greenberg yelled up to him. “This fucking thing is empty! Whose idea of a joke—”

“I was on the desk all the time,” Buddy said. “No one went by me. I’d swear to it. It must have happened on Carty’s shift. What’s the name on that one?”

“McDougall, Randall Fratus. What does this abbreviation inf. mean?”

“Infant,” Buddy said dully. “Jesus Christ, I think we’re in trouble.”

TWELVE

Something had awakened him.

He lay still in the ticking dark, looking at the ceiling.

A noise. Some noise. But the house was silent.

There it was again. Scratching.

Mark Petrie turned over in bed and looked through the window and Danny Glick was staring in at him through the glass, his skin grave-pale, his eyes reddish and feral. Some dark substance was smeared about his lips and chin, and when he saw Mark looking at him, he smiled and showed teeth grown hideously long and sharp.

“Let me in,” the voice whispered, and Mark was not sure if the words had crossed dark air or were only in his mind.

He became aware that he was frightened—his body had known before his mind. He had never been so frightened, not even when he got tired swimming back from the float at Popham Beach and thought he was going to drown. His mind, still that of a child in a thousand ways, made an accurate judgment of his position in seconds. He was in peril of more than his life.

“Let me in, Mark. I want to play with you.”

There was nothing for that hideous entity outside the window to hold on to; his room was on the second floor and there was no ledge. Yet somehow it hung suspended in space…or perhaps it was clinging to the outside shingles like some dark insect.

“Mark…I finally came, Mark. Please…”

Of course. You have to invite them inside. He knew that from his monster magazines, the ones his mother was afraid might damage or warp him in some way.

He got out of bed and almost fell down. It was only then that he realized fright was too mild a word for this. Even terror did not express what he felt. The pallid face outside the window tried to smile, but it had lain in darkness too long to remember precisely how. What Mark saw was a twitching grimace—a bloody mask of tragedy.

Yet if you looked in the eyes, it wasn’t so bad. If you looked in the eyes, you weren’t so afraid anymore and you saw that all you had to do was open the window and say, “C’mon in, Danny,” and then you wouldn’t be afraid at all because you’d be at one with Danny and all of them and at one with him. You’d be—

No! That’s how they get you!

He dragged his eyes away, and it took all of his willpower to do it.

“Mark, let me in! I command it! Hecommands it!”

Mark began to walk toward the window again. There was no help for it. There was no possible way to deny that voice. As he drew closer to the glass, the evil little boy’s face on the other side began to twitch and grimace with eagerness. Fingernails, black with earth, scratched across the windowpane.

Think of something. Quick! Quick!

“The rain,” he whispered hoarsely. “The rain in Spain falls mainly on the plain. In vain he thrusts his fists against the posts and still insists he sees the ghosts.”