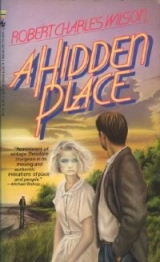

Текст книги "A Hidden Place"

Автор книги: Robert Charles Wilson

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

Chapter Eleven

Nancy told it the best way she could, shivering in the damp. She wished she could be Anna, could communicate these truths with that same reassuring candor. But she was only herself. She did not look at Travis’s eyes, the fear and the cynicism there were too frightening.

Her voice was quavery and small in the silence. Anna, she said carefully, was from another time and place, another world, very far away in one sense, but ” in another very near; a world that was very ancient but that had always had a tenuous connection with this one… and she closed her eyes, and the words echoed in her memory…

“The passage between is freer for us,” Anna had said, her eyes wide and her emaciated body very still, “though it can work the other way, too. There is the ancient human tradition of the vision-quest, the spirit-walk. The Greeks at Eleusis, the American Indians in the wilderness, the stylites on their pillars. They all want the same thing. To see—if only for a moment. A glimpse of the Jeweled World.” And Nancy, listening, had felt a curious kind of recognition, intuitive, as if she had seen that place, too, as if it had been vouchsafed to her in some long-forgotten dream. A shining antipodes. She saw it in the darkness. A landscape of perfect shapes.

“Faerie,” she said breathlessly. “The land under the hill.”

“In a way. But a real place, too. Substantial. The laws of nature function differently there, I think, but they do function, and as remorselessly as here. A place, not a land of abstractions.” She sighed, a papery sound. “When we cross—and we have our own vision-quests, our own spirit-walks—we’ve been called by other names. Demon, succubus, changeling…”

“But you’re not that.”

“It depends,” Anna said, her smile sphinxlike, “on who you ask.”

Nancy struggled to shape her thoughts. “But I mean … in spite of everything, it doesn’t seem as if … I mean, you know history and you speak English and you have a name. …”

All that, Anna said, was a kind of camouflage. When she’d entered this world she had put on humanity like a suit of clothes… but a real humanity, flesh and blood and psyche, there was a physical change. Creath Burack had found her newly minted, days old; lost, but with a functioning human body and a store of human knowledge. “All the teeming voices of humanity are there to delve and borrow. …”

“You read minds?”

“In a sense. The minds beneath minds. I can’t read your thoughts, if that’s what you mean.”

“You invented Anna Blaise.”

“In a way I made her out of parts. But I am Anna Blaise. Anna Blaise is a translation of myself.”

“There was Creath. And Grant Bevis. And Travis Fisher.”

“Understand,” Anna said. She touched Nancy’s forehead, and again there was that quaver of strangeness. “In here, you—all of you—are many things at once. Male and female. Adult and child. Paradoxes upon paradoxes. Whereas we are made more simply. Think of Anna Blaise as the pole of a magnet. Think of the way a magnet works on iron filings—quite without volition.”

“Magnets,” Nancy said, “have two poles.”

“You are,” Anna said, “very astute.”

Nancy took a cigarette and gave one to Travis, the last of a dearly bought packet of Wings. She trembled, lighting it. The dampness of the air almost smothered the match flame. She allowed herself to look at him as he inhaled a lungful of smoke, held it a moment, released it like steam into the cold. His face was unreadable.

“Lost,” Travis said. “You said she’s lost?”

And Nancy felt a surge of hope.

Two of them had journeyed here together.

It was not traveling in any sense Nancy would recognize, Anna had said, but she could imagine it that way if she wished: an ocean voyage, say. There had been a storm; in effect the two of them had been shipwrecked. Lost and separated in a huge and quite “foreign land. They were essential to one another; separately they were powerless, embedded in their disguises, more human than not. Alone she was powerless even to attempt to leave this place. Together it might be possible… but they had lost one another. They were castaways.

She had needed a place to conceal herself. The elementary femaleness of the Anna Blaise persona helped: Creath had secreted her in the boardinghouse like a buried treasure. It had not been pleasant but it had been necessary; the environment in which she found herself, its seasons and its people, was wildly hostile. And, touching her, Nancy found herself imagining it: Anna-made-human lost in the prairie darkness, disoriented, Creath Burack wrapping a blanket around her, pulling her into the car, into the hot miasma of his maleness, the stink of his cigars; Liza Burack gazing on with a disapproval that would mature into a kind of stony; impotent hatred. In all this, her terrible aloneness.

“But this Other,” Nancy said. “He’s looking for you?”

She nodded.

“Has been—since you moved in with the Buracks?” “Yes.”

“He’s like you?”

A frown had crossed her face. “No.” “A man.”

“In his human avatar, yes. Nancy, listen: among us male and female mean something very different. Apart, we’re very nearly two distinct species. Bone is not like me.”

“That’s his name? Bone?”

“The name he was given. His disguise is poorer and his nature is more elementary. He’s been searching, yes, but we’ve only just made contact. It’s easier,” she said faintly, “when the need is more profound.”

A tramp, drawn by the cigarette smoke, stood staring at Nancy and Travis. She had taken to wearing the whalebone knife as a matter of course and her hand strayed to it now. The tramp’s face was a cipher, eyes lidded and expressionless. His hands were buried in his pockets.

“Come on,” Travis said.

The rain had tapered off, though the thick gray clouds still tumbled overhead. The prairie was shrouded and wet-smelling, the horizon invisible. They walked a distance along the railway tracks, Travis scuffing up the gravel between the ties. She wondered what was going on in his head. Whether he believed her… but he must, she thought; it was no more fanciful than his own intuition,– it was Travis, after all, who had insisted that Anna was not human. “Bone,” he said abruptly, “what the hell kind of name is that?”

“He’s not like her.”

“She needs him?”

“She’s sick.”

“Sick how?”

“Sick with the separation. They were never meant to be apart so long. Their time ran out, and it’s hurting her.”

We can’t sustain ourselves this way, she had said: we can’t sustain our humanity. Or be sustained if we lose it. The changes must come. …

“This Bone: he’s sick, too?”

She said, “Yes, but it’s not the same kind of sickness. The need is intense in both of them. Bone is different: he doesn’t talk much, he has trouble with ideas, maybe doesn’t even know for sure where he is or where he came from. Only that he’s trying to find her. He’s like an animal following an instinct. He’s big, he’s very strong, but the time is running out for him, too. But he knows where to find her, which direction to go: she thinks he’ll be here. Soon.”

“Christ God.” He shook his head. “Nancy—”

“You saw some of it, didn’t you? You saw her Change.”

“I don’t ever want to see it again.”

The afternoon had edged on. The sun was headed down. Nancy felt cold, tired, hungry. Her flat-soled shoes were all scuffed up and there were burdocks clinging to her cloth coat.

“I don’t trust her,” Travis said, still, gazing back at Haute Montagne where it stood on the prairie, the towers of the granaries stark against the sky. How small it looked from here, Nancy thought. “She could be anything,” he said, “you ever think of that? We don’t know what she is or what this Bone is. Only what she tells us. And she’s lied before.”

“I believe her,” Nancy said.

“Maybe she picked us because we’d believe her. Not Creath, not Aunt Liza, not anybody else in town.”

“Because we’d understand.” Oh, Travis, she thought, I’ve touched her, I know—but how to explain that? “Out at the tracks that night, she saw something in you, a goodness—”

“Or a gullibility.”

“Travis, what is it? Why does she frighten you so?”

He was a long time answering. The answer had sprung up in him but there was no way to articulate it: because of what Mama was, he thought, because of how she died; because of what he had done with Nancy and what he had wanted to do with Anna Blaise. The whole sour mess of it. He felt torn inside: some wound there had been opened. Fundamentally, he distrusted the femaleness of the Anna-thing; like all femaleness it concealed too much.

“It had to be us,” Nancy was saying. “She took a chance, you know, telling us anything at all. But she needs somebody. She can’t live out these two weeks without somebody to bring her food, somebody to help her through the Changes—somebody who’ll know and somebody who’ll do it anyway. You know anybody else who’d do that? Anybody else back there!”

“It’s only a town,” Travis said. “They hate us.”

He looked at her. She was skinny and dragged-out looking. Her hair was tangled. “You still believe that? You’re too good for them?”

She straightened defiantly and her eyes went shiny with tears. “This town,” she said, “this goddamn town—I am too big for this town!”

And a look of surprise washed over her.

“That’s why she picked us,” Travis said gently. “We’re alone. Cut off.”

“Like she is.”

“Maybe.” He added, “When wolves go after a sheep, the first thing they do is cut it off from the flock.”

“That’s just crazy. She’s so weak!”

“What about this Bone? What if they do get together?” He thought of his vision of Anna Blaise– wet wings unfolding behind her. “They don’t care about us.”

“Come tomorrow,” Nancy said. “Talk to her.” She said, her voice rising, “I told you what you wanted to know!”

“I didn’t make any promises.”

“Travis, the only goddamn wolves around here are the ones in Haute Montagne, and they are circling, and they have cut me off—both of us—and, Travis, maybe you can ride away from it all, but– goddammit—I can’t, and they’re gonna bring me down!”

He thought of Anna Blaise in her damp shack, her pale skin stretched fine, her eyes huge and burning; he thought of this Bone, hardly human, tracking her across the night. He closed his eyes. The Jeweled World. He trembled, thinking of it: of what she had been and what she might become. And what he stood to lose or gain in the process.

“Tomorrow,” Nancy said.

“Maybe,” he said softly. “Maybe.”

Chapter Twelve

Creath Burack nodded, not cordially, at the sullen-faced boy who had come through the door of his office.

He felt content, alone here in this pineboard room. There was the reassuring rumble of the compressors, the metallic smell of the dust, the calendars tacked on the wall like pieces of mosaic. He had spent much of his life here. He sat in the wooden reclining chair with his feet on an upturned waste-basket. Too long in this position and the narrow bands of the back-support bit into his spine like teeth. He was getting older; comfort, like most things, could be taken only in moderation. He stirred dully, sat up, blinking.

“Heard you might have a job free,” the boy said.

Creath Burack squinted.

“You,” he said, “you’re Greg Morrow, aren’t you? Bill Morrow’s kid?” He nodded to himself. He remembered Bill Morrow, a fat granary worker who used to show up at the First Baptist stinking of flax and bathtub liquor, sullen little dark-skinned wife who had died of rheumatic fever three years back– yeah. “Yeah, I seen you before. Aren’t you working over at the mill?”

“Got laid off,” the boy said. “Heard about your job.”

My Christ, the older man thought, but he is not handsome. Round ugly face. And his lip curled like that. Creath felt a swelling resentment of the boy’s youth, plainly misspent. He could think of no good reason not to show this kid the gate. But play him, first, he thought—like a fish on a line. “What job’s that?”

“The one the shit-heel farmboy lost,” Greg said, maybe sensing that he was not welcome here.

“Shit-heel farmboy, huh.” Creath was secretly amused. “You got a strange idea how to beg for a job.”

“Fuck it, I’m not begging,” Greg Morrow said. He turned to the door.^

Some instinct made Creath say, “Hang on a minute.”

Greg hesitated.

“It’s not much of a job,” Creath said. “Pick up trash, stand in on the machine sometimes, deliver sometimes, lift and load always.” He smiled. “It pays shit.”

Greg remained sullen but appeared confused, as if he had been praised and scolded both at once. That was good.

“Try it out,” Creath said. “See if you can get a handle on it.”

“Now?” The kid brightened. “Right now.”

That had been before lunch.

The kid worked straight through, mopping down the loading docks with scalding water and ammonia. Then the work crew filtered back, gazing at Greg with mute curiosity, at the enthusiastic way Creath played foreman to him,– slowly they had caught on, finding him scutwork of their own, lolling against the limp boards of the icehouse while Greg Morrow manhandled the big slabs in and out with an inadequate pair of tongs. The muffled laughter became audible, and at one point Greg looked around with a dark, startled suspicion in his eyes. But everyone had turned away.

After the five o’clock bell he showed up back in Creath’s office, steaming wet and obviously exhausted. Natural enough, Creath thought. He had done the work of two men.

“What time do I come in tomorrow?”

“Sleep late.” Creath grinned at him. “The job’s not available.”

“What the fuck—”

“We’re not hiring. Thanks anyway.”

“You bastard, you owe me a day’s pay!”

“I don’t remember signing anything,” Creath said mildly. “And watch your dirty mouth.”

Greg did a long slow burn but he did, at last, turn to leave. Creath felt an immense, perverse satisfaction. Damn but hadn’t the kid done a job with that mop!

But Greg hesitated and turned back to him now, smiling faintly, and his posture took on that easy insolence again. Creath said, “You too dumb to find the door?”

“Maybe I’m good for something after all.” Creath was instantly suspicious. “I don’t get it.” “You want her back?” “Want who back?” “You know.”

The insinuation was plain.

Creath felt beads of sweat break out on his forehead. Guilt and doubt gusted over him both at once. By God, he thought, I have put all that behind me.

Demons of lust, he thought. Demons of—of—

“I can find her,” Greg Morrow said, and he was smiling now, a secret and insinuating smile. “I know where she is. I can find her.”

I have put all that behind me.

“I don’t want to know,” Creath said faintly. “I don’t want to know!”

“Maybe you don’t. That’s okay. I’ll get lost.” He opened the door.

“No,” Creath heard himself say. “Wait. …” “Huh?”

“Be in at nine,” Creath said weakly.

Greg Morrow only nodded.

The kid was gone, then, and Creath sat back, swabbing his forehead with his big checked handkerchief. After a moment he took out the bottle of Saskatchewan corn whiskey he kept in the bottom drawer, Volstead Act or no Volstead Act; he drank from the neck of the bottle. Backsliding. But there were worse demons than Demon Drink.

The memory of the tent revival came back blindingly strong—the fine high euphoria that had blossomed like a thorny wildflower behind his eyes. The two ecstasies warred inside him. Ecstasy of sin, ecstasy of faith. He felt his heart falter in his chest.

I know where she is, the boy had said. I can find her.

Was it possible? That she was still here, still in Haute Montagne, hidden somewhere—was that truly possible?

No, Creath thought. It’s a ruse, a trick, a lie. It cannot be. It must not be allowed.

He reached a second time for the bottle.

God forgive me, he thought. I want her back.

His hand was trembling.

Still smarting with humiliation, Greg Morrow nursed the spastic Model T down the south end of The Spur, out past the scabbed towers of the granaries to his daddy’s property, with its sprung doors like torn hip pockets and its elephant’s graveyard of rust-pocked farm machinery.

Inside, his old man was asleep. Dusk gathered complex shadows about the prostrate form on the sofa in the front room. A bottle of hooch, inevitably, lay on the plank floor next to him.

Greg experienced a wave of disgust. He harbored no illusions about the sort of man his father was. Shit-poor, he thought, shit-drunk—and shit-stupid.

He stomped into the kitchen. There were cans of charity food from the churches, a few, in the cupboard. Hoover, one of his father’s five aging and incontinent cats, sat smugly on the wooden counter-top. Greg put out his arm and swiped Hoover down to the peeling linoleum.

Shit-stupid, he thought, that was the sum of it. This town had reduced his old man to a kind of ruin, a living analogue of the junk machines rotting in the front yard, and there was no reason for it but a blind, complacent stupidity.

Greg had not done all that well in school and had left, in any case, when he was old enough to work. But he had discovered a simple truth that raised him above the level of his old man.

Small actions, he thought, have big consequences.

You pull strings. That was how it was done. He had watched the people who ran the town, and that was how they did it. Nothing big, nothing showy. A tug here, a tug there.

And more: Anyone could do it.

Today, for instance. Maybe he had endured that humiliation at the ice plant. But he had also got himself a job.

And all it took, he thought, was a word. The right word.

There were times he wished he could communicate this truth to his father. If they beat on you, he wanted to say, you don’t have to beat back, and you don’t have to take it (though his father had done both, copiously)—you just have to watch. And know. And learn the words to say, the strings to pull.

Revenge was available.

In his head Greg had kept a running tabulation of every humiliation he had suffered, every beating he had endured. His own and his old man’s. The memories were polished with handling.

He thought of Creath Burack. He thought of Travis Fisher and Nancy Wilcox.

Strings, he thought. Lots of strings there.

He opened a can of beans and chased Hoover, yowling, out the back door.

Night had begun to fall.

In the darkness under the railway trestle Travis dreamed.

His dreams were not coherent. Delirious with the cold, he was ravaged by visions. He dreamt of the Pale Woman, and recognized her from a lifetime of dreams: she was pure, virginal, white-robed; her face was his mother’s face except when it was Anna’s or, somehow, Nancy’s. He knew from looking at her that she was untouched, utterly female, desirable– and he was ashamed of his own arousal. He wanted to touch her, defile her. And in the dream she was always moving away from him, retreating, unapproachable; her purity, like some fundamental principle, was preserved.

He woke shivering in the darkness as the night freight passed by above him. Sparks showered down and the roaring made his ears ache dully. When the train was gone there was only the sound of the prairie wind rattling in the high beams of the trestle.

He sat up, frightened, the residue of the dream lingering in the dark air. If he closed his eyes he could see her, the Pale Woman, as clearly as ever. She was, he realized, the woman his mother had not been, the woman his mother had failed to be; she was the woman he had looked for in Nancy, too, and most particularly in Anna Blaise.

The woman he had not found.

And he thought, shivering in the darkness, stricken: What if there is no such woman? What if she doesn’t exist?

Chapter Thirteen

Nancy spent the next day at the switchman’s shack waiting for Travis to arrive, leaping up with a mixed gladness and terror whenever she heard a sound outside.

“He might come,” Anna admitted, her white stick-fingers laced in her lap. “If he does, he will have taken a step away from being—” She hesitated. “The thing he might have become.” “He’ll be here,” Nancy said. Anna was visible in the band of daylight falling through the open door. No one would mistake her for human now, Nancy thought. The Change had progressed too far. It was, Anna had explained, the natural sloughing-off of her humanity. But her need, the sickness of her separation from Bone, was also visible. The exaggerated orbit of her joints, the wildness of her eyes and the thinness of her lips, had only emphasized her decline. Nancy looked at her and thought of a child’s toy, one of those loose-jointed slat puppets connected by bits of string… but made of china or porcelain rather than wood, and with bright blue balls of glass for eyes.

“He might,” Anna said, “but he might not. You should be prepared for that.”

Her plain prairie accent, coming from that body, was like a bad joke. But no, Nancy thought, not really. The voice, for all its plainness, was high and lilted, a kind of song, like singing heard far off on a summer night, and it was that voice, the reassurance of it, that helped keep Nancy sane through all this. Physically Anna was frighteningly strange; she was alien, now unmistakably so; but that wonderful half-familiar voice contained a calming cadence, a necessary link to the known.

“He’ll come,” Nancy said, and: “What do you mean—a step away from being what!”

“He’s two people. You must have seen that. Part of him is the Travis who has been so often hurt and victimized, and that part of him is sympathetic. He wants to help. But there is this other Travis Fisher, the Travis Fisher who believes in a kind of female purity, who believes that women ought to be pristine, above nature, incorruptible—all the things he thought I was.”

“Or the things you chose to show him.”

“Maybe I deluded him. If so, it was not by choice. It’s in my nature to be a mirror. Like Creath, he looked at me and saw a hidden part of himself.”

It was at such times, Nancy thought, that Anna seemed most wholly alien. Her eyes grew distant, as if she were looking directly into Travis’s skull, peering somehow into the coral growths of his unconscious mind. Nancy had taught herself something about modern psychology; yes, she thought, there is some truth in all this. “He believed in you.”

“He thought I was that woman. But he wanted you to be that woman, too. The woman he once believed his mother was.”

His mother, Nancy thought, yes, my God. “He must feel—betrayed—”

“Betrayed and angry. And that’s the other part of Travis Fisher: this huge anger. A part of him hates us—hates both of us—for not being pure enough or good enough.”

“There were times,” Nancy said, nodding, “the way he’d look at me—”

“He suppresses the hate, of course. He believes in chivalry. And unlike Creath he is not by nature cruel. But the hate has had a good deal of trauma to feed on. It could displace his better instincts.”

“But if he understood—”

“It’s not as simple as that. All this lives in the deepest part of him.”

“Phantoms,” Nancy said scornfully. “Ghosts.”

Anna shrugged. “Travis’s virtuous woman is a kind of ghost, yes. Like your ghost.” Nancy frowned. “The ghost,” Anna went on, “of your father. Or the man you invented out of the memory of your father. The ghost you’ve been trying to placate all these years. …”

“I thought you couldn’t read minds.”

“Only the deepest parts.” After a moment: “I’m sorry.” Her voice was faint. “I shouldn’t have spoken.”

Nancy was astonished to find her eyes filling with tears. She dabbed her face with the wrists of her blouse. It was all crazy, of course. Anna was not human,– Travis was right; she could hardly be expected to understand how real people thought or felt. “It’s not really like that.” She turned back defiantly. “He was—he—”

But Anna held up her hand, pleadingly. “Truly, I’m sorry. I have to rest now.”

Nancy went out into the meadow—the sun was disturbingly low in the sky—to wait for Travis. He would come. He must. But the meadow was empty and the wind cut through this threadbare winter coat like a darning needle. She hugged herself and went back to the meager shelter of the switchman’s shack. Inside, she let her head loll against the fibrous wallboards and closed her eyes. When she opened them she gasped.

Anna was convulsing.

Her eyes had rolled up into her head. Her skin, always alarmingly pale, was dead-white now, blood-drained. The convulsions traversed her body; her spine bucked and arched over the thin stained mattress… “Anna!”

This was not the Change, Nancy thought dazedly, this was something else. Something new, something worse. She put her arm around the alien woman to steady her.

The contact was electric. So quickly that she could not steel herself, her mind was filled with hideous images.

The earth lurching under her feet. Fear. Fear and the footsteps behind her. A train roaring blackly in the near distance. The cold wind, the footsteps, the gun, the shockingly loud sound of it, pain invading her body in huge radiant arcs—

–and she was distantly aware of the scream that filled the confined space of the shack: it might have been Anna’s, or hers, or both.

Liza Burack picked up the phone on the second ring. She had been answering telephones more eagerly this autumn now that she had come to believe in the possibility of good news. “Yes?”

“Liza!” the voice on the other end boomed out. “This is Bob Clawson!”

She had not seen him since the Rotarian picnic four years ago, but Liza remembered the high-school principal well: the ample belly, the prissy three-piece suit he had worn, coat and all, all through that hot July day, fearful of betraying his dignity to the handful of high-school students who had shown up with their parents. “Good to hear your voice,” Liza said courteously. “Can I help you?”

“Actually, it was Creath I wanted to speak to.”

“Creath is putting in an extra hour at the ice plant.”

“Bull for work? Eh? Well, that’s good. That’s fine. I can call again another time.”

“May I tell him what this is about?” Liza was curious now, because Bob Clawson was town council, Bob Clawson was white collar, Bob Clawson didn’t phone up just anybody… and at that long-since picnic he had avoided the Buracks the way he might have avoided a rabid dog.

“Just a little group some of us are getting together,” Clawson said amiably. “I heard about your speech at the Women last week. Meat and potatoes Americanism, my wife tells me. Not enough of that going around these days.”

“Bad times,” Liza said automatically.

“Some of us are more than a little concerned.” Liza imagined who “some of us” might be: Bob Clawson knew every judge and lawyer and realtor in the county. “We wanted to get together, talk about doing something to protect the town. Thought Creath might be interested.”

She felt a small thrill run through her. Of course, their rehabilitation could not be complete so soon; Clawson must have some secondary reason for wanting Creath, some dirty work he wanted done. But it was a stepping stone. She thought, we are at least on probation.

“I’m sure Creath will be anxious to talk to you,” she said.

“Well, I appreciate that, Liza.”

“Yes.”

“Good talking to you. I’ll call back, then.”

“Yes.” She thought of asking for his number but decided against it: better not to appear too anxious. “Thank you,” she said.

She hung up the phone and leaned a moment on the dust mop, waiting for her heart to calm its aggravated beat.

Everything was happening so quickly!

The evening was naturally anxious. Creath absorbed the news without visible reaction—only smoked his cigars and played the big Atwater-Kent radio. But Liza could tell by the way he held the paper creased in thirds, not turning the pages, that it was on his mind.

The phone rang at half past eight. Creath waited for Liza to pick it up. Bob Clawson. She passed the receiver to her husband; he motioned her out of the parlor and pushed shut the door with his foot.

Liza lingered in the hallway. She was not eavesdropping. Her posture was erect, disdainful. Still, she thought, words have a way of slipping through doors.

Tonight, however, Creath’s tone was suppressed; the conversation went on a maddeningly long time, but all Liza heard was “yes” and “no” and … if she had made it out correctly… one other word.

By nine Creath was out of the parlor. He went directly to the kitchen and poured a drink of water from the tap. From the way the veins stood out on his face Liza guessed he would have preferred hard liquor. “What is it,” she said, “what?”

“Nothing much,” Creath said: but it was the same falsely casual tone in which he had customarily lied to her about Anna Blaise (a memory she quickly suppressed). “Just Bob Clawson getting together some bullshit—pardon me—some two-bit smoker. Bunch of men griping about the Red Menace. Harmless, I guess.” lie took a big swallow of water. “Guess I’ll go.”

Liza nodded dutifully. Secretly, however, she retained her suspicions. She did not think “two bit” would describe any organization Bob Clawson would ever bother to get involved with.

And as for “smoker”—well, that was possible. Anything was possible. But the word that had drifted through the parlor door had not sounded much like “smoker” or “two bit.”

The word Liza had heard was “vigilante.”

Later that evening Liza got a phone call of her own: Helena Baxter calling to let her know that the votes from the last meeting had been counted; that the results were not official, of course, until the announcement the following weekend, but—speaking strictly off the record—it looked like Liza had won a landslide victory.

Travis watched the switchman’s hut from the reedy bank of the Fresnel River, dusk gathering around him like the cupped palms of two huge black hands. He hadn’t eaten for two days—his money had run out and there had been nothing to scrounge at the hobo jungle—and voices circled like birds inside him.

He was not sure how he had come to this. He was dead broke, his clothes were torn and stiff with dirt, the only way he had of washing himself was to dip his body in the frigid river water. All this was foreign to him. Mama had always been scrupulously clean; she had kept their small house soaped and dusted and aired. The thought created in him a wave of nostalgia so physical it left him weak-kneed. And his traitorous memory chose that moment to echo back something Creath had said (it seemed like) a long time ago: Well, we all know where that path inclines, I guess.