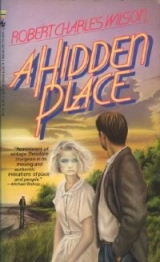

Текст книги "A Hidden Place"

Автор книги: Robert Charles Wilson

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

I am a guest in his home, Travis thought, teeth clenched. I cannot say what I think. But he looked at Creath Burack with a barely restrained loathing.

“Creath,” Liza said, gently warning.

“It’s only what the boy has to hear. Better he should know it now than come to it hard later on.”

Liza, silent, delivered a steaming pot roast to the table. The heat and humidity of it filled the dining room,– Travis felt a drop of sweat travel down his chest. His stomach felt shriveled.

“Because,” Creath went on, “and I say this honestly, I won’t accept second-best from you down at the plant. Some might say it was favoritism, my hiring you on at all. Now I don’t believe that. I don’t mink it is un-Christian to help a family member in need. The opposite. But charity does not extend to indulgence. That’s all I’m trying to put across. Work is what is required. Maybe things have been easy for you before. But the sad truth is that they will not be easy now.”

Travis said quietly, “When Mama was sick I hired the men to harvest. I drove a tractor, and a team of horses when we sold the tractor. And when we couldn’t hire hands I took what I could of the harvest myself.”

“Well,” Creath said, “we know what the upshot of that was, don’t we?”

“Creath,” Liza said quickly, “will you give us the blessing?”

Creath muttered a may-God-be-thanked and was reaching for the boiled peas when the Buracks’ other roomer came down the stairs.

She had been silent on the carpeted steps and Travis was startled at the shadow. He had forgotten about the attic room. He stood up from the table, a gesture his mother had taught him was polite when a woman enters.

There was a brief, tense silence.

“Travis Fisher,” Liza said distantly, “this is Anna Blaise.”

He stared at her a long moment before he remembered to take her hand. “Meet you,” he said clumsily, and she made a movement like a curtsy.

He knew he was being impolite, but she was shockingly beautiful. She was young, Travis thought, maybe his own age, but the longer he looked at her the less certain he was. She was radiant and smooth-skinned but her eyes contained depths he did not associate with youth. Her face was round. Her hair was blond and rough-cut and tied back behind her with an alluring carelessness. She gazed at the floor as if uncertain what she ought to do or say; but beneath this shyness there was an inference of great poise, an economy of motion. Travis felt clumsy next to her.

“Why don’t we all sit down,” Liza said flatly.

“Yes,” Anna said, and her voice was a match for the rest of her, calm and modulated, like the playing of a distant flute. She sat down opposite Liza Burack and made the table a symmetry.

For a time, no one spoke. The rattle of their cutlery was loud in the silence.

Covertly Travis watched the girl eat. She kept her eyes downcast, took small portions, used her knife and fork daintily. It occurred to him to marvel that the Buracks had taken in another boarder. He remembered his aunt and uncle being intensely private people. Family people. Times were bad, he thought; they must need the money. But where had she come from?

“I’m from Oklahoma,” he ventured to say. “Near Beaumont.”

Her eyes were on him very briefly. “Yes,” she said. “The Buracks told me you were coming.”

“You from around here?” “Not too far,” she said. “Working in town?”

“I work here,” she said. “In the house. I do sewing. I—”

“For Christ’s sake,” Creath said, “leave her alone.”

Travis was mortified. “I’m sorry,” he said.

Anna Blaise smiled and shrugged.

Something wrong here, Travis thought. Odd and wrong. But he went about his eating.

“Didn’t make but a dent in that pot roast,” Liza said with a sigh when they were finished. She rose, moaning a little, and picked up the big china platter. Anna stood up unbidden and took her own plate, Travis’s, Creath’s.

There was the sound of clattering in the kitchen, a gush of running water.

Creath withdrew a big Virginia cigar and made a ceremony of lighting it. He looked at Travis for a time over the glowing tip.

“Don’t think I don’t know what’s happening,” the older man said.

“Sir?”

“Keep your voice down.” He sighed out a plume of smoke. “You think I don’t know. But I do. The heat, the summer—and you look at her—you have feelings. But there will be none of that in this house. Don’t answer me! This is not a conversation. This is the rules. She is way out of your class, Travis Fisher.”

Travis groped for an answer, astonished. But before he could speak Liza had come back from the kitchen with syrupy wedges of blackberry pie laid out on china plates.

“My!” Creath said expansively. “This is a treat.”

* * *

It was round about midnight when Nancy Wilcox walked past the Burack house on DeVille.

She was coming from the open field where the railway trestle crossed the Fresnel River, where Greg Morrow had left her when she refused to let him put his hand up her skirt.

Greg was a pretty rough character, oldest son of a granary worker. He owned a decade-old Tin Lizzie with a blown cylinder in which he squired around whichever female he could talk into a ride. He chewed tobacco and he used what the Baptist Women called “gutter language.” Precisely the kind of date her mother would disapprove of… which was maybe why Nancy had agreed to go with him in the first place. His crudity was kind of fascinating.

Ultimately, however, Greg was not the person Nancy wanted to do it with. If she had had any doubts, the events at the trestle had settled them. She was not a prude; she had read about free love in a book by H. G. Wells before her mother caught her with it (and had the small volume deleted from the town library); she had even done it a couple of times before, with a boy named Marcus whose family had since moved west.

But not with Greg. Greg seemed to think it was owed him, something that was his by right, and Nancy did not feel obliged to encourage him in this delusion. So he had kicked her out of the Lizzie down by the trestle, which made her a little nervous because lately there had been hoboes gathering there; she had seen their fires flickering in the angular darkness under the railway bridge. But she just walked steady and kept her head about her and pretty soon she was back among the streetlights and the box elders. She would catch righteous hell for getting home so late, of course. But in a way she was glad. She liked this time of night, liked to listen to the town ticking and cooling after a blast-furnace July day like this one had been. The midnight breeze on her face was soothing; the trees chattered to themselves in what she liked to imagine was a secret language.

She gazed up at the gray outline of the Burack house against the stars.

In the darkness it appeared to be just what that Mrs. Burack obviously imagined it was: a sturdy keystone in Haute Montagne’s social structure. You couldn’t see the peeling paint, the rain gutters clotted with mulch. Nancy smiled to herself, thinking of what her mother always said about the Buracks: something odd there, something definitely odd, and that girl in the attic!—about as talkative as a deaf-mute, and a lot less wholesome.

Nancy peered up at the attic room and saw a faint light flicker there, like fox fire behind the sun-yellowed blinds.

“Strange,” she said to herself…

And there was that Fisher boy, now, too, the one who had stopped by the diner this afternoon. There had been rumblings about his situation, a fatherless family, mother a runabout, hints of some darker truth. But that could have been just the Baptist Women’s rumor mill at work, Nancy thought, grinding a very modest kernel of truth. He had seemed nice. If distracted. He had left his magazine at the diner. Nancy had gazed a long time at the cover of it: horses, guns, a range of purple mountains. He is from far away.

She let the night air carry back her hair. She felt like a shadow sometimes, blowing through these night streets. Time carried her on like a cork on a wave—she was already eighteen—and she had lately become desperate with wondering: where was she bound? She sometimes dreamed of mountains (like the mountains on Travis Fisher’s pulp magazine), of cities, of oceans. She shivered, gazing up at the old Burack house.

She wondered what sort of person Travis Fisher was, and what he dreamed about.

In the attic room, the light flared brighter.

Travis lay in bed, exhausted but helplessly awake, an uneasy excitement running in him like a river. He felt the unfamiliar pressure of the mattress under him. He had covered his nakedness with a single sheet, because it was summer and all the heat in the house traveled up to these high narrow rooms and was retained there. The attic, he thought, must be sizzling.

She doesn’t make much noise.

Anna Blaise, he thought, tasting the name: Anna Blaise, Anna Blaise.

He had heard, during the long evening, the restless treadle of her sewing machine, her radio playing briefly. Then silence. Later on, the quick compression of bedsprings.

The house made its own sounds, sighs and moans. Travis had propped open the window with a hardware-store expansion screen and every once in a while a breeze picked up the corner of the sheet. Sleep, he thought, and it was a prayer now: sleep, oh, sleep.

Shortly after midnight he heard footsteps on the stairway beyond his door.

Slow, heavy footsteps coming up from below. Aunt Liza didn’t carry that much bulk—it could only be Creath.

This time of night! Travis thought.

The footsteps paused outside his door and then proceeded upward.

Strange, Travis thought.

And now they were over his head. Creath, for sure.

A brief, low burr of conversation. Anna’s voice like faraway music, Creath’s like the grumble of some rusted old machine.

The repetitive complaint of the bedsprings.

Jesus God Almighty, Travis thought, that poor little girl!—and he covered his ears with his pillow.

Chapter Two

The evenings were essentially the same for the next week and a half: an elaborate ritual dinner, Anna’s opacity and silences, Creath’s clenched-fist approach to conversation. Later there might be radio, Creath lighting up a cigar and occupying the parlor easy chair for the duration of “Amos Andy” or Ed Wynn or, Sundays, Father Coughlin’s “Golden Hour of the Little Flower.” Then everybody eased upstairs to hot and insulated beds, and Travis, if he stayed awake, might hear Creath tiptoeing into the attic room… not always, but too often. It forced Travis to look at his Aunt Liza’s nervous flutters with a greater degree of sympathy: she knows, he thought, she must know.

Weekdays Creath drove him down to the ice plant before dawn. The thought of all that ice had made Travis imagine the plant might be a nice place in which to endure this long summer. But—although he did sometimes enter the cool length of the storeroom where block ice lay stacked like uncut fragments from some fairy-tale diamond mine—most of his work was in the tin shed where the refrigerating machinery roared and thumped, perversely twenty degrees hotter than the outside air. The work he did was mostly lifting and cleaning, and he quickly learned that the other men who worked here, mechanics and loaders and drivers, considered him a liability, contemptible, the boss’s nephew. He ate bagged lunches alone in a weedy field beyond the loading dock, staring into the brown Fresnel River. The ice industry was doomed, Creath had said, victim of the goddamned Kelvinator. It might survive a while longer here in Haute Montagne, but orders were already way down for this time of year. Travis found the knowledge perversely consoling. The work itself was tedious and frustrating, and when the frustration threatened to overwhelm him he decided to ask Nancy Wilcox for a date.

That Friday evening after work he told Creath to let him off at the corner of Lambeth and The Spur. Creath accelerated his Model A pickup through a yellow light and said, “Your aunt will have dinner ready. You not hungry?”

“I’ll get something down here.” He avoided the older man’s eyes. “Maybe see a movie.”

“Waste of money,” Creath said, but he downshifted the truck and slowed long enough to allow Travis to leap out.

There were still a couple of hours of daylight left. The sky was a powdery blue, the shadows stark and angular. He went directly to the diner. Nancy Wilcox had not been on his mind nearly as much as Anna Blaise… but Anna Blaise was a mystery, at once violated and aloof, as unapproachable as a cat. Nancy was someone he might talk to.

She was there in the murky interior of the diner. An overhead fan stirred the air. The tables were all busy and there was a second waitress on duty. He sat at the counter, smiled, ordered the chuck steak and a coleslaw side and wondered how to approach her.

He was not shy with women, not in the ordinary sense, but he had had only a pittance of real experience. Back home only Millie Gardner, the neighbor girl, had spoken much with him, and by the time Travis left Millie was just turning twelve and had already begun to grow aloof. Other than that he had talked to his mother, his schoolteachers, a couple of girls doing what they obviously perceived as a kind of distasteful social work when he was left conspicuously alone at school functions. It was humiliating; but there were others who were, in a way, worse off; who were ostracized for some mental or physical deformity and not solely on account of their family situation. And although he had often enough prayed that it was otherwise, Travis knew, at least, that he was not despised altogether for himself.

But that was back home. This was a new place. Here it was still possible that Travis could expect some of what he had so far been pointedly denied. Nobody knew him here, and that simple fact was as tantalizing as a promise.

He lingered over the steaming plate of food, which he did not much want, killing time. There was no good opportunity to talk. Nancy moved deftly between the tall aluminum coffee urn and the soda fountain, balanced plates on her arms, pinned table orders on the silver carousel for the kitchen to pick up. He watched her pluck a strand of steamed black hair out of her eyes and thought: well, this is impossible. Nevertheless he lingered over his coffee and asked for refills. The hot black coffee made his heart beat faster. His eyes were on her constantly. And he thought: she at least notices me here.

In time the tables began to empty, the humidity eased. She filled his cup for the third time and said, “Eight o’clock.”

He looked at her, stupefied.

She put her elbows on the counter. “That’s when I get off. Eight o’clock. That’s what you want to know, isn’t it?”

“I guess it is.”

“I’ve seen the Cagney film at the Rialto but there’s a new one at the Fox. Jewel Robbery. William Powell and Kay Francis. You like William Powell?”

“He’s pretty good.”

Travis had seen three moving pictures in his life. She smiled. “Well, I guess I’m going over there after work.”

“I guess so am I,” he said.

She surprised him by stopping off at the Haute Montagne Public Library and slipping three fat volumes into the night depository: a Hemingway novel, a book on astronomy, and something by a German named Carl Gustav Jung.

Travis said, “You read all that?”

“Uh-huh.” She gave him that smile again: it was harder now, defiant, and he guessed she must have been ribbed about her reading. “Don’t you read?”

“Magazines mostly” In fact he had had a fair amount of time for reading in the long winters back home. She would already have seen the dime western; and he was not prepared to admit to the stacks of stolen, borrowed, or dearly bought science fiction and adventure pulps he had ploughed through. Not when she was dumping Carl Gustav Jung into the night slot.

They moved along the darkened sidewalks back toward Lawson Spur and the Fox Theater.

There was a short line at the ticket box and Travis saw other girls there, high-school girls or just older, and observed how they looked at Nancy Wilcox, the crabbed sidelong glances and covert stares. It was a phenomenon he recognized, and he thought: What is there about her? He paid for two tickets and they sat together in the mezzanine, gazing down silently for a time at the plush velvet curtains over the screen while a fat woman played overtures on the Wurlitzer. Travis felt the girl’s warm pressure next to him. She smelled good, he thought, some perfume and just a lingering indication that she had put in a long day in a hot restaurant. It was a wholesome smell. It aroused him and it made him nervous: he wondered what was expected of him, whether he should hold her hand or keep to himself. He did not want to insult her. Then the lights flickered down, the organ hissed into silence, the movie started. It was one of those cock-tail-and-evening-gown movies, everybody pronouncing calculated bon mots in rooms that seemed to Travis too impossibly large and lushly furnished. He watched in a sort of dazed incomprehension, and when Nancy pressed her body toward him he intertwined his arm with hers and they were, at least, that close.

After the movie they went for Cokes.

The Wilcox girl’s hair had strayed down in front of her eyes again. She probed at the ice with her straw and said, “You don’t go out much, do you?”

“Is it so obvious?”

“No, Travis. Nothing wrong. Just you seemed a bit uncomfortable is all.”

Travis was carefully silent.

She said, “I guess you were kind of a misfit back where you came from.”

“Your mother told you that?”

“Said as much, I guess, but that’s not what I mean. I mean the way you move, the way you talk. Very, I don’t know, wary. Like something’s going to jump out at you.”

“A misfit,” he said. “I guess that’s about it.”

“I’m a misfit. Did you know that?” She sipped her Coke again.

“Those books?”

“Partly. Nobody reads in this town. Miss Thayer who works at the library, she doesn’t even read. But that’s not all of it.” She said, as if offering a vital confidence, “I don’t get along with people.”

“I know what that’s like,” Travis said.

“Partly it’s my mother. She makes a profession out of being righteous. She believes the world is going straight to hell. So I guess the pressure’s on me to live up to all that. I’m supposed to be perfect—a saintly little female Imitation of Christ. I guess I just, ah, cracked.” She laughed. “She’s so afraid of everything, you know, Travis? Afraid and suspicious. And I’m the opposite.”

He smiled distantly. “Never afraid?”

“Not of what she’s afraid of.”

“What’s she afraid of?”

Nancy gazed out the big window of the diner. It was way past dark now. All the cars had their lights on. “Love. Sex. Politics. Dirty words.” She waved her hand. “All that.”

“Oh,” Travis said, taken aback.

“Are you afraid of those things?” She was staring at him now.

“Hell, no,” he said, hoping it was not a lie.

But she laughed and seemed to loosen up. “No,” she said, “no, I don’t guess you are.” And she drained her Coke. “Walk me home?”

At the corner of the street where she lived Nancy turned and touched his arm. “I don’t want my mother to see us. She’ll be on to us soon enough anyway. You can kiss me if you want, Travis.”

The offer surprised him. He was clumsy but earnest.

She nodded thoughtfully then, as if she had entered some particularly revealing notation in a private notebook. His hands lingered on her.

“One day,” she said, “you have to tell me the truth about it.”

“About what?”

“You know. Where you came from. What happened there.” She hesitated. “Your mother.” “She was a very fine woman,” Travis said. “Is that the truth?” He stepped away from her. “Yes.”

Chapter Three

Three Sundays after Travis arrived in Haute Montagne, Liza Burack made up her special mille-feuilles for the Baptist Women’s bake sale.

The day was dusty and hot, as all the days had been that parched summer, and the baked goods were set up on the lawn of the First Baptist, in the shadow of the high quatrefoil stained-glass windows which were the building’s only adornment. Reverend Shaffer had brought out the big sprucewood tables and Mrs. Clawson had provided drop cloths. The edibles were displayed thereon—quite artistically, Liza thought, the candies and pastries in attractive circles like tiny works of art. Shirley Croft’s almond cake had been given, as usual, pride of place. Shirley herself stood guard against the circling flies, flailing with an elder branch and wearing the sort of vigilant expression her late husband might have displayed to the Germans at the Battle of the Somme. Faye Wilcox was at one end of the table, Liza at the other, like the two polarities of an electrical cell.

I will just drift down, Liza thought. After all. Appearances. And what with the way things were going… well.

She moved lightly past the creamhoms and butter cookies.

She liked these times best, she thought, all the people around her, the aimless chatter. It was like being pulled in many directions at once. If she closed her eyes she could almost imagine herself floating, the baked goods like scattered islands in an ocean of afternoon, the heat on her like a benediction. Everything condensed in this minute point of experience.

But such ideas worried her (her thoughts strayed too easily these days) and she forced herself to stay on course: Faye Wilcox, she instructed herself, talk to Faye.

The Wilcox woman was heavy and hostile. Her arms were laced under her bosom. It looked for all the world as if her body were some unpleasant excresence that had leaked, unavoidably, into public sight. Well, Liza thought, it’s that outfit, hardly better than a sack. But who am I to talk? She glanced with momentary embarrassment at herself. Her cornflower dress was streaked with white from the morning’s baking. She had neglected to change. And had she combed her hair? Lord, Lord, where was her mind?

“Lovely afternoon, Liza.” It was Reverend Shaffer, cruising across the broad green church lawn. He was a young man and there was, Liza thought, something almost feminine about him, such a contrast with the Reverend Kinney who had died just two autumns ago. Reverend Shaffer used the pulpit to deliver obscure parables, to pose questions; Reverend Kinney had been more concerned with answers. It was, Liza thought, too symptomatic of the changes that had overtaken the nation, the town, her life. But she mustn’t dwell on that. “It is nice,” she said.

The flies were intense, the heat debilitating, there were no customers.

“Everybody loves your napoleons,” the Reverend said.

“Mille-feuilles,” Liza said automatically. “Pardon me?”

“Mother always called them mille-feuilles. Mary-Jane—that’s my sister—my, how she loved those pastries! She was always pestering Mother. ‘Make up your mill-fills, Mama, make up your mill-fills!’ She ate and ate and never got fat. Not like me____”

“And how is your sister?” the Reverend asked, puzzled.

“Dead,” Liza said. “Dead and, I presume, in hell.”

Reverend Shaffer frowned. “The judgment’s not ours to make, Mrs. Burack.”

“You didn’t know Mary-Jane, Reverend. Please—take a mille-feuille.”

But the Reverend only gazed at her coolly and drifted away.

How different it had been when she was a girl. In those days there had been virtue and vice, distilled and pure essences between which one might choose. Not this muddying, not this terrible confusion. Liza straightened her spine and gazed at the Wilcox woman—Nancy’s mother.

“Love your butter tarts,” she said.

Faye Wilcox looked at her as if from a great distance. “You haven’t even tried one, Liza dear.”

“Oh, I couldn’t. But they’re so beautiful. Just so perfect.”

“Thank you,” Faye said.

“Did you see my mille-feuilles?”

“Lovely as always.”

She is so hard, Liza thought sadly. Hard as granite. At one time, of course, they had been friends– allies, at least; wary, but with the same goals before them. In those days (it would have been three years ago: she remembered the annual picnic, “Summer 1929” printed on the invitation cards) Liza had been the leading light of the Baptist Women. It was Liza who had organized the letter campaign to the public school board concerning their thoughtless promotion of the Darwin Theory in the high-school textbooks; it was Liza who had chaired the Temperance Committee. Everyone agreed that without Liza Burack the Baptist Women would have been a vastly less effectual organization.

But then things had begun to happen. Things over which she had no control. That Blaise girl had moved in. Creath began to act strangely. Mary-Jane had come down sick off in Oklahoma, and there was no way Liza could visit, not merely on account of the distance but because of the sort of woman Mary-Jane had allowed herself to become.

The upshot of it all was: Liza faded. She had heard other people use that expression. Faded. It was an odd word. It made her think of flowers left too long in a vase. She thought with some astonishment: I have faded.

And of course Faye Wilcox had stepped into the vacuum Liza had left; and now it was Faye who organized the letter campaigns, the library boycotts; now it was Faye everyone looked to for guidance.

But Faye had her own Achilles’ heel, Liza thought, suppressing a certain vindictive pleasure. She had that daughter of hers, who was quite notorious. Faye herself complained sometimes, though she was shrewd enough to blame it on the schools…

And now, Liza thought, Nancy Wilcox and Travis Fisher were going together.

“I suppose,” Liza said, “you’ve heard about Nancy and my sister’s boy?”

Faye adopted a stern equanimity. Her eyes were steely, buried in small effusions of flesh. “I know they’ve been seen together.”

“My goodness, hasn’t Nancy talked it over with you?”

“Nancy is not inclined to do that.” “Faye, that girl doesn’t appreciate what you do for her.”

Faye relaxed a little. “Indeed she does not. I’m sometimes grateful Martin isn’t alive to hear the back talk she gives me. It would break his heart.”

“You deserve better.”

“It’s in the Lord’s hands,” Faye Wilcox said primly. “And Travis? Have you had any trouble—?”

“Creath says he is unhappy at work. But no real trouble, no, thank God.”

“The times …” Faye Wilcox said.

“Oh, yes.”

“Of course, the boy’s mother …”

“Tragic.” Liza added, “I mean, her death.”

“One wonders if tendencies are inherited.”

“He is a hard worker, in spite of what Creath says. He seems quite stable here. The influence of the home counts for so much, don’t you think?”

Faye nodded grudgingly and brushed the air above her butter tarts. Flies buzzed.

“Still, it could be worse,” Liza said. “The two of them.”

Faye Wilcox gazed across the lawn, the baking asphalt street, her eyes unfocused.

“It could be,” she admitted.

There, Liza thought. It had been decided. In that strained admission, a truce. Nancy and Travis would be allowed to continue seeing each other.

It was, for both Liza and Faye, the best of the meager alternatives. Faye had accepted it… grudgingly, no doubt, for it returned to Liza a measure of control.

Now, Liza thought, now what does this mean? What does this portend for the future?

“Those tarts just look so good,” Liza said.

Faye held one out to her by the paper wrapper, an offering. “Please.”

“Thank you,” Liza said, biting deeply into the pastry.

The ripe sweetness of it exploded in her mouth.

Trav and Nancy made Friday night a regular thing. Twice, as the month crawled toward September, he met her on Saturday as well. When there was nothing at the Fox or the Rialto they walked up The Spur toward the railway depot or out to the wide, grassy fields where the Fresnel ran beyond the town. Nancy knew where the wild strawberry patches were, though the dry season had yielded very few berries. And, slowly, Travis had come to know Nancy.

He liked her. He harbored an admiration for her frankness, her outrageous willingness to defy convention. She had quite consciously put herself in a position Travis had long occupied against his will: outsider, loner—“misfit” was the word she liked to use. And that fascinated him. But it disturbed him, too, the lightheartedness of it, as if she were playing a game with something really quite dangerous, something she did not altogether understand… compromising her femininity with this reckless curiosity. He liked her, but in a strange way he was also afraid of her.

They had come to the strawberry fields again. The sun was going down now, the day’s heat beginning to abate, darkness rising from the eastern horizon beyond the ruin of a shack where, Nancy said, an eccentric railway switchman had once lived. The town was not far away—the train depot was hardly more than a quarter mile distant, obscured by a stand of trees—but their isolation seemed complete. They found a few berries and then Nancy put out a blanket over a bare patch of ground by the tumbledown hut, and they sat there watching the river run with their backs against the sun-warmed wood. A breeze had come up… the twilight breeze, Nancy called it.

She held his hand, and her skin was warm and dry.

She said after a time, “You like that place? The Burack place?”

Travis shrugged. “It’s all right.”

“You don’t sound too enthusiastic.”

“I don’t have much choice. It’s a place to live.”

“You make money down at the plant?”

“Some.”

She smiled knowingly. “I bet that Creath Burack siphons off most of it for rent. Am I right?”

“He takes a share. I save a little.” She was leading up to something, Travis thought.

“How about that girl upstairs?”

“Anna?” He shrugged uncomfortably. “I don’t see much of her.”

“She’s a big mystery, you know. Everybody talked about her for a while. Still do sometimes.”

“Really? She’s so quiet—”

“Travis, that’s a major crime in itself. But there’s more to it. There must be. Sure, she’s quiet. Nobody knows where she comes from or how she happened to end up in Haute Montagne. One day she was living at the Buracks’, that’s all anybody knows. But there are rumors. Man named Grant Bevis, used to live next door to your aunt and uncle, married man—he left town real quick not too long after Anna Blaise moved in. Anna takes in sewing but she never shows her face in town. Answers the door sometimes… probably gets all her work that way: people take her sewing just so they can get a glance at her.” Nancy gazed up at a solitary cloud. “They say she’s beautiful.”