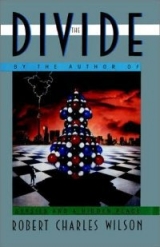

Текст книги "The Divide"

Автор книги: Robert Charles Wilson

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 14 страниц)

6

Bad night for Amelie.

The rain didn’t let up. Worse, she felt as if a similar cold cloudiness had invaded the apartment. Benjamin was quiet all through dinner, which was spaghetti and bottled sauce with some extra garlic and hamburger; the kind of meal Amelie assumed a man would like, substantial, with the steam from the cookpot fogging the windows. Amelie seldom had the opportunity to fix dinner. But today was her day off; she had planned this in advance.

Benjamin was quiet all through the meal. He didn’t pay attention to the food, ate mechanically, frowned around his fork.

She put on the kettle for coffee, brooding.

It was that woman, Amelie knew, the one who had come looking for John—the one who had driven Benjamin home. She had said something to him; she was on his mind. Amelie wanted to ask what this was all about, but she was scared of seeming jealous. Of seeming not to trust him. Maddeningly, Benjamin didn’t talk about it either. His silence was so substantial it was like an item of clothing, a strange black hat he had worn into the house. She tried to negotiate around it, to accommodate herself to his mood … but it was too obvious to really ignore.

She stacked the dishes and put Bon Jovi on the stereo. The tape-player part still worked, but Roch’s little two-step had twisted the tonearm off its bearings. Amelie hoped Benjamin wouldn’t notice. She didn’t want to tell him about Roch.

The truth was that Amelie didn’t feel too secure about men in general. She imagined that if she had a shrink this was the kind of thing she would confess to him. I don’t feel too secure about men. It was one of those things you can know about yourself, but knowing doesn’t make it better. Maybe this was because of her shitty adolescence, her absentee father—who knew what? On TV these problems always had neat beginnings and tidy, logical ends. In life, it was different. The time when she came here from Montreal with Roch—that was an example.

It’s funny, she thought, you say a word like prostitution and it sounds truly horrifying. Like “AIDS” or “cancer.” But she had never thought of it that way when she was doing it. She met a couple of other girls who had been on the street a long time and they talked about hooking or turning tricks, but those words didn’t apply, either. Not that she was too good for it: it was just that her mind veered away from the topic. She was surviving. Being paid for sex … it just wasn’t something you thought much about, before or during or after. And when you stop doing it, you don’t have to think about it. And so it goes away. It doesn’t show. No visible scars … although sometimes, in her paranoid moments, Amelie wasn’t so sure about that. Sometimes she developed the urge to hide her face when she rode the buses or waited on tables.

But by and large it was something she could forget about, and that was why Roch had pissed her off so intensely. Reminding her of that. Worse, acting like it was something she might do again. As if, once you do it, you’re never any better than that: it’s what you are. Trained reflex. Go fetch. Lie down and roll over.

But really, that was just Roch. Roch always had a hard time figuring out what anybody else was doing or thinking. One time, when he was nine or ten, Roch asked a friend of Amelie’s named Jeanette how come she was so ugly. Jeanette turned brick red and slapped his face. Roch wasn’t hurt, his feelings weren’t hurt, but he was almost comically surprised. Later he asked Amelie: what happened? Did he break a rule or something?

All Roch wanted was a little cash, a loan. He hadn’t meant anything by it.

She was too sensitive, that was all.

What was really frightening was the question of how Roch might respond to the beating John had given him. Because, the thing was, Roch could not forget a humiliation. He harbored grudges and generally tried to pay them back with interest.

But, Amelie told herself, there was no point in dwelling on it now.

She dried the dishes, put the towel up to dry, joined Benjamin in the main room. The TV was a black-and-white model Amelie had bought from a thrift shop, attached to a bow-tie antenna from a garage sale. The rooming house didn’t have cable, so they watched sitcoms on the CBC all evening. Benjamin didn’t say a word—just folded his hands in his lap and seemed to watch, though his eyes were foggy and distracted. Sometime around midnight, they went to bed.

* * *

She was almost asleep, lying on her back in the dark room listening to the sound of the rain against the window, when he said:

“What if I went away for a while?”

She felt suddenly cold.

She sat up. “Where would you go?”

He shrugged. “I don’t want to talk about that part of it.”

Everything seemed in sudden high relief: the faint streetlight against the cloth curtains, the coolness of the bedsheets where they touched her thighs. “Is it connected with this woman?”

Saying it out loud at last.

He said, “She’s a doctor.”

“Are you sick?”

“Maybe.”

“Is it about—” Another taboo. “About John?”

He nodded in the darkness, a shadow.

Amelie said, “Well, I don’t want you to leave.”

“But if I have to?”

“I don’t know what that means—’have to.’ If you have to, then you just do it.”

“I mean, would you be here for me.”

His voice was solemn, careful.

“I don’t know,” she said. Thinking: Christ, yes, of course I’ll be here!

He was the best thing in her life and if there was even a chance of him coming back … but she couldn’t say that. “Maybe,” she said.

He nodded again.

He said, “Well, maybe it won’t happen.”

“Talk to me,” she said. “Before you do anything.”

“I’ll try,” Benjamin said.

And then silence. And the rain beating down.

* * *

They woke a little after dawn and made love.

There was one frightening moment, when Amelie looked into his eyes, and for a second—not longer than that—she had the terrifying feeling that it was John looking down at her, his cold and penetrating vision a kind of rape … but then she blinked, and the world slid back into place; he was Benjamin again, moving against her with a passion that was also kindness and which she had allowed herself to think of as love.

The vision of him crowded out her fear.

He was Benjamin. And that was good.

7

For the rest of that rainy October week Susan immersed herself in the mystery of John Shaw.

I’ve talked to him, she thought. In a sense, I know him…

But beyond that loomed the inescapable fact:He is not entirely human.

There was no way to reconcile these ideas.

She tried to stay in her hotel room in case he called, but by Thursday morning she was overcome with cabin fever. She left a firm order at the desk to take any phone messages and set out on foot with no real direction in mind.

The rain had stopped, at least. The sky was overcast and the wind was cold, but even that was gratifying after the monotony of recycled hotel air. She walked west, away from the downtown core. Toronto was a banking city, crowded with stark office towers; its charm, she had decided, was peripheral to this, in Chinatown or the University district. She turned north along University Avenue, willfully avoiding the direction of Benjamin’s office. Shortly before noon she found herself between a phalanx of peanut carts and the granite steps of the Royal Ontario Museum, with pennies in her pocket and nowhere else to go.

Inside, the museum was all high domed ceilings and Egyptians, botanical displays and gemstones under glass. Susan appreciated these, but she especially liked the dark vaults of the dinosaur arcade, cool Pleistocene fluorescence and faint voices like the drip of water. The articulated bones of Triceratops regarded her with the stately indifference of geological time. Susan returned the look for almost a quarter of an hour, reverently.

Beyond Triceratops, the corridor wound away to the left. She eased back slowly into human history; where she was startled, turning a corner, by the Evolution of Man.

It was one of those museum displays that compare the skull sizes, tools, curvature of the spine across the eons. Here was Homo habilis leading the human march out of Olduvai, but surely, Susan thought, the entire concept was archaic: did anyone still believe evolution had proceeded in this reasonable arc? From stone club to Sidewinder missile, here at the pinnacle of time?

But she supposed John would have had a place here, too, if anyone had known about him. Dr. Kyriakides had once told her that he wanted to engineer the next step in human evolution. “A better human being. One who would make us obsolete. Or at least embarrass us for our vices.”

So here would be John, leading the march toward the future, a little taller and a little brighter and in his hand—what? A pocket H-bomb? A neutrino evaporator? Or he might be as pristine as Dr. Kyriakides had envisioned him … as weaponless and innocent as a child.

She turned away. Suddenly she wanted the high ceilings of the main arcades, not this cloistered space. But before she left she paused before the diorama of Neolithic Man, stooped and feral in wax, wincing at the first light of human awareness. Our father, she thought. Mine and John’s, too; as obdurate, inscrutable, and foreign as every father is.

* * *

Still he did not call.

Friday afternoon she phoned Maxim Kyriakides at his office at the University.

He said, “I should have come myself. Forced the issue. Then he could not have avoided me.”

“I don’t think that’s what he needs. That is—I had the impression—it would have made things worse.”

“You may be right. Still, I could come there if necessary.” He added, “I suppose I’m feeling guilty about demanding so much of your time.”

“It’s all right.”

“Is it really? You weren’t so obliging when you began the project. I had to talk you into leaving.”

“I think it’s different now—meeting him and all. I wasn’t sure what to expect. Some kind of monster.”

“Are you sure he’s not?”

She was quietly shocked. “I don’t know what you mean.”

“Only that it’s easy to forget that he is what he is. He has abilities you won’t have encountered. His point of view is unique. He may not feel bound by conventional behavior.”

“I understand that.”

“Do you really, Susan? I hope so. I worry that you might be projecting your own concerns onto him. That would be a mistake.”

“I know.” (But she was blushing.) “There’s no danger of that.”

“Then I’m sorry I mentioned it.” He was being very Old World now, very charming. “I really do appreciate the work you’re doing, Susan.”

She thanked him—cautiously.

He said, “Stay as long as you like. But keep in touch.”

“I will.”

“And ultimately—if there’s nothing we can do—”

“I know,” she said. “I’m prepared for that.”

She was lying, of course.

* * *

Benjamin called that evening. The call was brief, but Susan could hear the anxiety in his voice.

“There’s a problem,” he said.

“What is it? Is it John? Is he sick?”

Cold night and the city bright but impersonal beyond the windows.

“He’s thinking of leaving town,” Benjamin said. “You want the truth? I think he’s afraid of you.”

“We have to talk,” Susan said.

* * *

She met him at an all-night cafeteria on Yonge Street.

The club next door was hosting a high-powered reggae band; the bass notes came pulsing through the wall. Susan ordered coffee and drank it black.

Benjamin came in from the street shivering in his checkerboard flannel jacket. She marveled again at how unlike John he was: nothing to distinguish this man from anyone else on the street. He smiled as he pulled up his chair, but the smile was perfunctory.

He shucked his jacket and ordered a coffee. He added cream and sugar, sipped once, said: “Oh—hey, that’s good. I needed that.”

“You look tired.”

“I am. Ever since we had our talk … I guess I’m kind of reluctant to fall asleep. Don’t know who’ll wake up. He wants more time, Susan. All of a sudden he’s fighting me.”

“I didn’t know he had a choice.”

“You come to terms with something like this. But there was never any real conflict before. I mean, you don’t understand what it’s like. It’s not something you think about if you can help it. You just live your life. I think … John was fading because he didn’t really care anymore. He let me do what I wanted and he wasn’t around much. Now … this whole thing has stirred him up.”

Susan leaned forward across the table. “You can tell that?”

“I feel him wanting to be awake.” Benjamin sat back in his chair, regarding her. “You think that’s a good thing, don’t you?”

“Well, I—I mean, it’s important to know—”

“I had to take a couple of days off.” Benjamin smiled ruefully. “John was kind enough to phone in sick for me.”

“You said he was thinking about going away?”

“Both of us have been. I talked to Amelie about it. I asked her if it would be okay, you know, if I didn’t see her for a while.”

“What did she say?”

“Basically, that it would be okay, but it wouldn’t make her happy.” He took a compulsive gulp of coffee. “If we do this—if we go for treatment—would it be possible for Amelie to come along? There’s not much to keep her here. I mean, budget permitting and all.”

“I’d have to talk to Dr. Kyriakides. It may be possible.” She hoped not. But that was petty. “You were saying about John—”

“John’s pulling in the opposite direction. I don’t usually have much access to his thoughts, you know, but some things come through. He’s thinking of leaving, but not for treatment. He wants to hit the road. Get out of town. Run away.”

“From me?”

“From this doctor of yours. From the situation But yes, you’re a part of it. I think you disturbed him a little bit. There’s something about you that worries him.”

“What? I don’t understand!”

Benjamin shrugged. “Neither do I.”

“You think there’s a chance he’ll really do it?”

“Leave? I don’t know. I really don’t. Maybe, if he panics. This is all new territory for me, you know. It’s hard to explain, but … I was just getting used to living a life. I mean, I know what I am. I’m a shadow. I’m aware of that. I was always a shadow. I’m something he made up. But I look around, I have thoughts, I see things—I’m as alive as you are.” He shook his head. “I don’t want to go back to the way it was before. You know what I like, Susan? I like the sunshine. I like the light.” His gaze was very steady and for a moment he did remind her of John. “So is that why you’re here? To send me back into the shadows?”

Susan inspected the Formica tabletop. “No. No one wants that.”

“Because you’re right. There is something happening to us. Something up here.” He tapped his head. “I can feel it. Like the boundaries are loosening up. Things are stirring around. And I don’t know where that’s taking me.” He added, “I have to admit I’m a little bit scared.”

Susan took his hand. “Both of you need help. We have to make sure both of you get it.”

“The thing is, I don’t know if I can do that. I’ll do what I can. Whatever happens, I’ll try to keep in touch. I’ll let you know where we are. But I’m not in charge here. It’s not my choice.”

“Tell me what I can do.”

“I don’t know.” He smiled wearily. “Probably nothing.”

8

Tony Morriseau was hanging out at the comer of Church and Wellesley minding his own business when he saw the Chess Player coming toward him.

Actually, stalking him was more like it. This was unusual, and Tony regarded the Chess Player’s lanky figure with a faint, first tremor of unease.

Tony knew the Chess Player from the All-Nite Donut Shop on Wellesley. Tony had never spoken to him, but the guy was a fixture there, poised over his board like a patient, predatory animal. Hardly anybody ever played him. Certainly not Tony. Tony wasn’t into games. His experience was that the Chess Player didn’t talk and nobody talked to the Chess Player.

Still, Tony recognized him. Tony was a quarter Cree on his mother’s side and liked to think he had that old Indian thing, keeping his ear to the ground. Tony made most of his money—which was not really a lot—selling dope out of the back of his 78 Corvette, parked just down the block. His profit margins weren’t high and his only steady customers were the local gay trade and some high school kids. Still, Tony was a fixture on the street; he had been here since ’84. Same Corvette, same business. He told himself it was only temporary. He wanted to make significant money, and this—dealing in streetcorner volume at a pathetic margin, from a supplier who had been known to refer to Tony as “pinworm”—this wasn’t the way to do it. He would find something else. But until then …

Until then it was business as usual—and what did this geek want from him, anyhow?

Tony pressed his back against a brick wall and gave the Chess Player a cautious nod. The evening traffic rolled down Church Street under the lights; an elderly Korean couple strolled past, heads down in abject courtesy. Tony looked at the Chess Player, now directly in front of him, and the Chess Player stared back. Big deep hollow eyes, round head, burr haircut. He made Tony distinctly nervous. Tony said, “Do I know you?”

“No,” the Chess Player said. “But I know you. I want to buy something.”

“Maybe I don’t have anything to sell.”

The Chess Player reached into his pocket and pulled out a roll of bills. He peeled a fifty off the top and stuffed it into the pocket of Tony’s down vest. Tony’s heart began to pump faster, and it might have been the money but it might also have been the look on the guy’s face. He thought: Am I afraid? And thought: Fuck, no. Not me.

He transferred the bill to his hip pocket. “So what is it you want?”

“Amphetamines,” the Chess Player said, and Tony was briefly amused at how dainty he made it sound: amphetamines.

“How many?”

“How many have you got?”

Tony did a little mental calculation. He began to feel better. “Come with me,” he said.

Down the block to the Corvette. Checking the guy out sideways as they walked. Tony kept most of his stock in the back of the ’Vette. He had been ripped off twice; and while that was something you expected—he was not a volume dealer and he could eat the occasional losses—it was also something you didn’t want to set yourself up for. But Tony was fairly smart about people (his Cree instinct, he told himself), and he didn’t believe the Chess Player was a thief. Something else. Something strange, maybe something a little bit dangerous. But not a thief.

Tony opened the car door and rooted out a Ziploc bag of prescription pharmaceuticals from the space under the driver’s seat. He held the bag low inside the angle of the door, displaying it to the buyer but not to the public. “Some of these suit your fancy?”

“All of them.”

“That would be—you’d be talking some serious money there.”

He named a price and the Chess Player peeled off the bills. Large money amounts and no haggling. It was like a dream. Tony stuffed the cash into his rear pocket, a tight little bulge. He could go home. He could have a drink. He was prepared to celebrate.

But the Chess Player leaned in toward him and said, very quietly and calmly, “I want the car, too.”

Tony was too startled to react at once. The Corvette! It was his only real possession. He had bought it from a retired dentist in Mississauga for a fraction of what it was worth. Put some money into it. The fiberglass body had been through some serious damage, but that was purely cosmetic. Under the hood, it was mainly original numbers. “Fuck, man, you can’t have my car—that’s my car.”

But it came out like a whine, a token protest, and Tony realized with a deep sense of shock that he was afraid of this man; it was just that he could not say exactly why.

Big, almost luminous eyes peering into his. Christ, Tony thought, he can see right through me!

Without blinking, the Chess Player pulled out his roll of bills again.

Tony stared at the cash as it came off the roll. It was like a machine at work. Crisp new money. He counted up to $5000; then—without thinking—he said, “Hey, look, I paid less than that for it … it needs bodywork, you know?”

The Chess Player put the money in Tony’s vest pocket. The touch of his fingers there was weirdly disturbing. “Buy a new car,” the Chess Player said. “Give me the keys.”

Be damned if Tony didn’t do just that. Handed them over without a word. Mysterious.

He would spend a lot of long nights wondering about it.

The Chess Player was about to climb in and drive away when Tony shook his head—it was like waking up from a bad dream into a hangover—and said, “Hey! My property!”

“Take what you want,” the Chess Player said.

Panicking, Tony retrieved ten ounces of seeded brown marijuana and a milk carton of Valium and stuffed them hastily into a brown paper A P bag.

The door slammed closed as the Corvette pulled away.

He watched as the automobile faded into the night traffic, southbound on Church, all the while thinking to himself: What was that? Jesus Christ almighty!—what was that?

* * *

John Shaw stopped off at the apartment to pack a change of clothes and leave a note.

Within ten minutes he had folded every useful item into two denim shoulderbags, including the bulk of the money he had withdrawn from his private accounts. The note to Amelie was more difficult.

He hesitated over pen and paper, thinking about the man who had sold him the Corvette.

He wasn’t proud of what he’d done. It was a skill he had mastered a long time ago, a finely honed vocabulary of body and voice. With the right gestures and the necessary words, he could intimidate almost anyone—play the primate chords of fear, anger, love, or distaste, and do so at will. For a time, when his contempt for humanity had reached its zenith, he did it often. It was a means to an end, as irrelevant to ethical considerations as the shearing of a sheep.

Or so he had thought.

That time had passed; but he was pleased by the outcome of the little experiment he had just performed on Tony Morriseau. Old skills intact. So much had been lost, obscured by unconsciousness. But maybe not permanently.

He had been asleep. Now he was awake.

He wrote:

Must leave. Try to understand.

He wondered how much more he ought to say. He could summon up Benjamin long enough to compose a more serious message. Could even play at being Benjamin without invoking the real, or potent, Benjamin. But he was reluctant to do that now … it was a mistake he had made too often before.

He debated signing Benjamin’s name, then decided it would be more honest, and possibly kinder, not to. In the end he simply hung the note (two sentences, five words) on the kitchen cupboard.

Hurrying to escape these small, crowded rooms.

* * *

The Corvette protested only a little when he nosed it onto the expressway and into the light midnight traffic northbound out of the city. He had been awake for two days now and some of the old clarity had come back to him. He was able to read the condition of the Corvette’s engine through the grammar of its purrs and hesitations, and his sense was that the vehicle was old but basically sound. Something catastrophic might happen, a crack in the engine block or an embolism in an oil line; but the pistons were turning over neatly, the gears meshed, the brakes were clean. With any luck, the car would get him where he was going.

The rain that had hovered over the province for the last two weeks had finally drifted off eastward. It was a clear, cold night. Between the glaring road-lights—growing sparse out here in farm territory—he was able to see a scatter of stars. He had always liked looking at the stars and sometimes felt a special connection with them, in their isolation in the dark sky. It was the kinship he felt for all lost, strange, and distant things.

The road arrowed up a long incline, an ancient glacial moraine, and suddenly the stars were right in front of him. Impulsively, he edged the Corvette’s gas pedal down. It was long past midnight and nothing was moving here but a heavily freighted lumber truck. He took the Corvette past it in an eyeblink. A brief taste of diesel through the cracked wing window, then onward. He watched the speedometer creep up. At eighty-five mph the Corvette was showing some of its age and neglect. He read a whiff of hot metal and oil, the spark plugs burning themselves clean.

He liked this—the farms and empty autumn fields blurring behind him; the sense of motion. But more than that. It was a private pleasure, uniquely his own. His reflexes and his sense of timing seldom came up against their inherent limits; it was exhilarating to push that envelope a little. He was very far from those limits even now—the speedometer still inching upward—but he was attentive, focused, and energized. Every shiver of the chassis or tremor of the road became significant information, raw data flooding him. He came up fast on a sixteen-wheel Mayflower truck and passed it, left the trucker’s horn screaming impotently down a corridor of cold night air.

This was a world only he was fit to inhabit, he thought, this landscape of speed and reflex. For anyone else it would be next door to death. For John it was a sunny meadowland through which his thoughts ran in a cool, rapid cascade.

There was a shimmy now from the rear end of the Corvette.

And he would have to slow down soon in any case, or risk running some radar trap or pushing the engine past its tolerances. In any case, it was time to fill the gas tank. But he allowed himself one moment more. This fine intoxication.

He was beginning to ease back on the gas pedal when the Corvette fishtailed coming around a slow curve.

He was on top of it instantly, manhandling the wheel, feeling the sudden change from vehicular momentum to deadly inertia. There was a long spin on the cool night pavement, tire treads fraying and screaming as the rear end wheeled around and the car tottered, wanting to turn over. John held onto the steering wheel, focused into this long moment … working with the car’s huge momentum, tugging it back from the brink, correcting and correcting again as the tires etched long V’s and Ws on the dark pavement.

He had the Corvette under control within microseconds. A moment later it was motionless on the shoulder of the road.

Sudden silence and the ticking of the hot engine. Wind in a dark October marsh off to the right of him.

A shiver of relief ran up his spine.

He looked at his hand. It was shaking.

He opened the glove compartment, tugged out the Ziploc bag, rolled an amphetamine cap into his mouth.

He dry-swallowed the pill and angled the car slowly back onto the highway, carefully thinking now about nothing at all.

* * *

Fundamentally, it was a question of past and future.

He took the first car ferry of the morning across Georgian Bay to the northern shore of Lake Superior. The North Shore was a stark landscape of pine and rock and the brittle blue Superior horizon. Gas station towns, souvenir stands, Indian reservations; black bear and deer in the outback. During the last world war, captive German military officers had been assigned logging duty in this wilderness. There were places, John understood, where their K-ration tins lay rusting under the pine needles and the washboard lumber roads. In summer the highway would have been crowded with tourists; but it was late in the year now and the campgrounds were vacant and unsupervised. He drove all day through the cold, transparent air; after nightfall he turned down a dirt track road to an empty campsite near the lakeshore. He zipped up his insulated windbreaker and stoked a kindling fire in one of the brick-lined barbecue pits; When he had achieved a satisfactory blaze he added on windfall until the fire was roaring and crackling. Then he settled back to rising sparks and stars and the lonely sound of Lake Superior washing at the shore. The fire warmed his hands and face; his back was cold. He heated a can of soup until the steam rose up in the wintery air.

When the meal was finished, he sat in the car with the passenger door opened toward the fire, thinking about the past and the future.

The past was simple. He contained it. He contained it in a way no other human being could contain it, as a body of mnemonic experience he could call up at will—his life like an open book.

Excepting the chaos of his earliest infancy, there was not a day of his life that John could not instantly evoke. He had divided his life into three fundamental episodes—his time with Dr. Kyriakides, his time with the Woodwards, his time as an adult. Four, if you counted the recent re-emergence of Benjamin as a new and distinct epoch. And each category was a vast book of days, of autumns and winters and summers and springs, each welling from its own past and arrowing toward its own future with a logic that had always seemed incontrovertible.

Until now. For most of his life he had been running toward the future as if it contained some sort of salvation. In the last few years, mysteriously, that had changed. The future, he thought, was a promise that might not be kept. Now he was running … not quite aimlessly, because he had a destination in mind; not toward the past, precisely; but toward a place where his life had taken a certain turn. A fork in the road. Maybe it would be possible to retrace his steps, turn the other way; this time, maybe, toward a genuine future, an authentic light.

He recognized the strong element of rationalization in this. Self-deception was a vice he had never permitted himself. But there comes a time when your back is to the wall. So you follow an instinct. You do what you have to.

A sudden, bitter wind came off the lake. The fire was dying. He banked the embers and then shut himself into the car, blinking at the darkness and afraid to sleep. He looked longingly at the glove compartment, picturing the bag of pills there. But he had to pace himself. He felt the fatigue poisons running through his body. No choice now but to sleep.

Anyway—he would need the pills more, later.

He watched the stars until the windows clouded with the vapor of his breath. Finally, with an almost violent suddenness, he slept.

* * *

He drove west into the broad prairie land.

Coming through Manitoba he ran into a frontal system, rain and wet snow that sidelined the Corvette in a little town called Atelier while the Dominion Service Station and Garage replaced the original tires with fresh snow-treads. John checked into a motel called The Traveller and picked up some books at the local thrift shop.