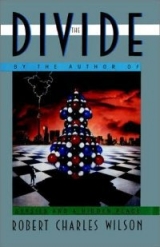

Текст книги "The Divide"

Автор книги: Robert Charles Wilson

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 14 страниц)

The Divide

by Robert Charles Wilson

PART 1

PRIVATE EXPERIMENTS

1

Such an ordinary house. Such an ordinary beginning.

But I want it to be an ordinary house, Susan Christopher thought. An ordinary house with an ordinary man in it. Not this monster—to whom I must deliver a message.

It was a yellow brick boardinghouse in the St. Jamestown area of Toronto, a neighborhood of low-rent high-rises and immigrant housing. Susan was from suburban Los Angeles—lately from the University of Chicago—and she felt misplaced here. She stood for a moment in the chill, sunny silence of the afternoon, double-checking the address Dr. Kyriakides had written on a slip of pink memo paper. This number, yes, this street.

She fought a momentary urge to run away.

Then up the walk through a scatter of October leaves, pausing a moment in the cold foyer … the inner door stood open … finally down a corridor to the door marked with a chipped gilt number 2.

She knocked twice, aware of her small knuckles against the ancient veneer of the door. Across the hall, a wizened East Indian man peered out from behind his chain-lock. Susan looked up at the ceiling, where a swastika had been spray-painted onto the cloudy stucco. She was about to knock again when the door opened under her hand.

But it was a woman who answered … a young woman in a white blouse, denim skirt, torn khaki jacket. Her feet were bare on the cracked linoleum. The woman’s expression was sullen—her lips in a ready, belligerent pout—and Susan dropped her eyes from the narrow face to the jacket, where there was a small constellation of buttons and badges: BON JOVI, JIM MORRISON, LED ZEPPELIN…

“You want something?”

Susan guessed this was a French-Canadian accent, nasal and impatient. She forced herself to meet the woman’s eyes. Woman or girl? Older than she had first seemed: maybe around my age, Susan thought; but it was hard to be sure, with the make-up and all.

She cleared her throat. “I’m looking for John Shaw.”

“Oh …him.”

“Is he here?”

“No.” The girl ran a hand through her hair. Long nails. Short hair.

“But he lives here?”

“Uh—sometimes. Are you a friend of his?”

Susan shook her head. “Not exactly … are you?”

Now there was the barest hint of a smile. “Not exactly.” The girl extended her hand. “I’m Amelie”

The hand was small and cool. Susan introduced herself; Amelie said, “He’s not here … but you can maybe find him at the 24-Hour on Wellesley. You know, the doughnut shop?”

Susan nodded. She would look for ” Wellesley ” on her map.

Amelie said, “Is it important? You look kind of, ah, worried.”

“It’s pretty important,” Susan said, thinking: Life or death. Dr. Kyriakides had told her that.

* * *

Susan saw him for the first time, her first real look at him, through the plate-glass window of the doughnut shop.

She allowed herself this moment, seeing him without being seen. She recognized him from the pictures Dr. Kyriakides had shown her. But Susan imagined that she might have guessed who he was, just from looking at him—that she would have known, at least, that he was not entirely normal.

To begin with, he was alone.

He sat at a small table in the long room, three steps down from the sidewalk. His face was angled up at the October sunlight, relishing it. There was a chessboard in front of him—the board built into the lacquered surface of the table and the pieces arranged in ready ranks.

She had dreamed about this, about meeting him, dreams that occasionally bordered on nightmares. In the dreams John Shaw was barely human, his head unnaturally enlarged, his eyes needle-sharp and unblinking. The real John Shaw was nothing like that, of course, in his photographs or here, in the flesh; his monstrosities, she thought, were buried—but she mustn’t think of him that way. He was in trouble and he needed her help.

Hello, John Shaw, she thought.

His hair was cut close, a burr cut, but that was fashionable now; he was meticulously clean-shaven. Regular features, frown lines, maps of character emerging from the geography of his fairly young face. Here is a man, Susan thought, who worries a lot. A gust of wind lifted her hair; she reached up to smooth it back and he must have glimpsed the motion. His head turned—a swift owlish flick of the eyes—and for that moment he did not seem human; the swivel of his head was too calculated, the focus of his eyes too fine. His eyes, suddenly, were like the eyes in her dreams.

John Shaw regarded her through the window and she felt spotlit, or, worse, pinned—a butterfly in a specimen case.

Both of them were motionless in this tableau until, finally, John Shaw raised a hand and beckoned her inside.

Well, Susan Christopher thought, there’s no turning back now, is there?

Breathing hard, she moved down the three cracked steps and through the door of the shop. There was no one inside but John Shaw and the middle-aged woman refilling the coffee machine. Susan approached him and then stood mute beside the table: she couldn’t find the words to begin.

He said, “You might as well sit down.”

His voice was controlled, unafraid, neutral in accent. Susan took the chair opposite him. They were separated, now, by the ranks of the chessboard.

He said, “Do you play?”

“Oh … I didn’t come here to play chess.”

“No. Max sent you.”

Her eyes widened at this Holmes-like deduction. John said, “Well, obviously you were looking for me. And I’ve taken some pains to be unlooked-for. I could imagine the American government wanting a word with me. But you don’t look like you work for the government. It wasn’t a long shot—I’m assuming I’m correct?”

“Yes,” Susan stammered. “Dr. Kyriakides … yes.”

“I thought he might do this. Sometime.”

“It’s more important than you think.” But how to say this? “He wants you to know—”

John hushed her. “Humor me,” he said. “Give me a game.”

She looked at the board. In high school, she had belonged to the chess club. She had even played in a couple of local tournaments—not too badly. But—

“You’ll win,” she said.

“You know that about me?”

“Dr. Kyriakides said—”

“Your move,” John said.

She advanced the white king’s pawn two squares, reflexively.

“No talk,” John instructed her. “As a favor.” He responded with his own king’s pawn. “I appreciate it.”

She played out the opening—a Ruy Lopez—but was soon in a kind of free fall; he did something unexpected with his queen’s knight and her pawn ranks began to unravel. His queen stood in place, a vast but nonspecific threat; he gave up a bishop to expose her king, and the queen at last came swooping out to give checkmate. They had not even castled.

Of course, the winning was inevitable. She knew—Dr. Kyriakides had told her—that John Shaw had played tournament chess for a time; that he had never lost a game; that he had dropped out of competition before his record and rating began to attract attention. She wondered how the board must look to him. Simple, she imagined. A graph of possibilities; a kindergarten problem.

He thanked her and began to set up the pieces again, his large hands moving slowly, meticulously. She said, “You spend a lot of time here?”

“Yes.”

“Playing chess?”

“Sometimes. Most of the regulars have given up on me.”

“But you still do it.”

“When I get the chance.”

“But surely … I mean, don’t you always win?”

He looked at her. He smiled, but the smile was cryptic … she couldn’t tell whether he was amused or disappointed.

“One hopes,” John Shaw said.

* * *

She walked back with him to the rooming house, attentive now, her fears beginning to abate, but still reluctant: how could she tell him? But she must. She used this time to observe him. What Dr. Kyriakides had told her was true: John wore his strangeness like a badge. There was no pinning down exactly what it was that made him different. His walk was a little ungainly; he was too tall; his eyes moved restlessly when he spoke. But none of that added up to anything significant. The real difference, she thought, was more subtle. Pheremones, or something on that level. She imagined that if he sat next to you on a bus you would notice him immediately—turn, look, maybe move to another seat. No reason, just this uneasiness. Something odd here.

It was almost dark, an early October dusk. The streetlights blinked on, casting complex shadows through the brittle trees. Coming up the porch stairs to the boardinghouse, Susan saw him hesitate, stiffen a moment, lock one hand in a fierce embrace of the banister. My God, she thought, it’s some kind of seizure—he’s sick—but it abated as quickly as it had come.

He straightened himself up and put his key in the door.

Susan said, “Will Amelie be here?”

“Amelie works a night shift at a restaurant on Yonge Street. She’s out by six most evenings.”

“You live with her?”

“No. I don’t live with her.”

The apartment seemed even more debased, in this light, than Susan had guessed from her earlier glimpse. It consisted of one main room abutting a closet-sized bedroom—she could make out the jumbled bedclothes through the door—and an even tinier kitchen. The place smelled greasy: Amelie’s dinner, Susan guessed, leftovers still congealing in the pan. Salvation Army furniture and a sad, dim floral wallpaper. Why would he live here? Why not a mansion—a palace? He could have had that. But he was sick, too … maybe that had something to do with it.

She said, “I know what you are.”

He nodded mildly, as if to say, Yes, all right He shifted a stack of magazines to make room for himself on the sofa. “You’re one of Max’s students?”

“I was,” she corrected. “Molecular biology. I took a sabbatical.”

“Money?”

“Money mostly. My father died after a long illness. It was expensive. There was the possibility of loans and so forth, but I didn’t feel—I just didn’t enjoy the work anymore. Dr. Kyriakides offered me a job until I was ready to face my thesis again. At first I was just collating notes, you know, doing some library research for a book he’s working on. Then—”

“Then he told you about me.”

“Yes.”

“He must trust you.”

“I suppose so.”

“I’m sure of it. And he sent you here?”

“Finally, yes. He wasn’t sure you’d be willing to talk directly to him. But it’s very important.”

“Not just auld long syne?”

“He wants to see you.”

“For medical reasons?”

“Yes.”

“Am I ill, then?”

“Yes.”

He smiled again. The smile was devastating—superior, knowing, but at the same time obviously forced, an act of bravery. He said, “Well, I thought so.”

* * *

Susan had no relish for this talk of illness. Her father’s illness had dominated her life for almost a year, keeping her on a dizzying rollercoaster of falling grades, missed deadlines, serial flights to California. In her graduate work she had been doing lab chores for Dr. Kyriakides, a study involving the enzyme mechanics of cancerous cell division; and it had been too painful an irony, that shuttle between the colonies of laboratory cells and her father’s bed, where he was dying of liver cancer. There is such a thing, Susan thought, as too much knowledge. She could not bear this meticulous understanding of the mechanism of her father’s death. She began to dream of malignant cells, chromosomes writhing inside their nuclei like angry, poisonous insects.

She suspected that the work Dr. Kyriakides gave her was a kind of charity. He had explained to her—the sophisticated European to the parvenu Californian WASP—that this was good and useful, that a person in mourning ought to have tasks to attend to. She was skeptical but grateful, and within a month she began to admit he was right: there was solace in the library stacks, in the numbers that marched so eloquently across the cool amber screen of her PC terminal. Her grasp of the work began to deepen. Dr. Kyriakides was a brilliant man; the book would be brilliant. Their relationship was not a friendship but something that, in Susan’s opinion, was much finer. She began to feel like a colleague. She took her own work more seriously.

Then, in August, Dr. Kyriakides had escorted her to a Creek restaurant in the mezzanine of a downtown hotel and had ordered impressively for both of them: medallions of lamb, an expensive wine. She had wondered with vast apprehension whether he meant to proposition her.

Instead he leaned forward and gazed into the bowl of his wine goblet. “A quarter of a century ago,” he said, “when I was just out of Harvard, and the government was paying so many smart people to commit such stupid acts, I did something I should not have done.”

It was the first time she’d heard the name John Shaw.

* * *

You can see his illness, she thought now. Waves of discomfort seemed to sweep across John’s face. He clenched his teeth a moment; then he said, “I’m sorry.”

“Dr. Kyriakides wants to see you,” Susan said. “The changes you’re going through aren’t necessarily irreversible.”

“He told you that?”

“He can help.”

“No,” John said.

“He told me you might react this way. But there’s no one else you can go to. And hewants to help.”

“I think it’s beyond that.”

“How can you be sure?”

“No offense intended. But my guess is as good as Max’s.”

“But,” Susan began, and then faltered. The pain he was suffering—if it was in fact a physical pain—overtook him again. The smile that had grown small and ironic now disappeared altogether. His knuckles whitened against the arm of the chair; his face seemed to change, as if a great variety of emotions had overtaken him, a sudden shifting … she thought of wind across a wheatfield.

She was frightened now.

She said, “What can I do? Can I help?”

He shook his head. “You can leave.”

The rejection was absolute. It hurt.

Susan said, “Well, maybe you’re right—maybe he can’t help.”

It was her own moment of cruelty. But it caught his attention. She persisted, “But what if you’re wrong? There’s at least a chance. Dr. Kyriakides said—”

“ Fuck Dr. Kyriakides.”

Susan was quietly shocked. She stood up, blushing.

“No, wait,” John said. “Leave your number.”

“What?”

“Leave your number. Or your address, your hotel room. Write it down. There’s paper over there. I’ll call. I promise. We can talk it over. But right now—I need to be alone right now.”

She nodded, scribbled down her name and the hotel, moved to the door. She turned back with the idea of making some final entreaty, but it was pointless. He had dismissed her; she was as good as invisible. He sat with his eyes closed and his head pressed between his hands … containing himself, as if he might explode, Susan thought as she hurried down the walk into the cold October night; or shutting out the world, as if it might rush in and drown him.

2

Amelie Desjardins understood very quickly that she was having a bad day—and that it would only get worse.

George, the manager at the Goodtime Grill, had put her on a split shift for the week. She worked from eleven-thirty to two-thirty, took an afternoon break, then she was back from five-thirty to eight o’clock at night. Which pretty much fucks up your day, Amelie thought, since she was too tired to do much after the lunch rush except trek back to St. Jamestown for a nap—her nap having been interrupted this afternoon by the woman looking for John.

Which was mysterious in itself, and Amelie might have worried more about it … but she had other things on her mind.

First she had come in to work a little late, and George climbed down her throat about it. Then there was prep and set-up, and it seemed as if every salt shaker in the place had gone empty all at once, which was a hassle. Then Alberto, the cook, chose this terrific time to start coming on to her, and that was a balancing act you wouldn’t wish on a trapeze artist, because you have to be on good terms with the cook. A friendly cook will juggle substitutions, fill your orders fast, do you a hundred little favors that add up to tips … but when you came right down to it Amelie thought Alberto was about as oily as the deep-fat fryer, which, not coincidentally, he seldom cleaned. Alberto rolled through the steamy kitchen like a huge, sweating demiurge, when he wasn’t peeking through the door of the changing room trying to catch a waitress in her underwear. So it was “You look really good tonight, Alberto,” and winking at him, and sharing some of her tips, and then getting the hell out of his way before he could deliver one of his patented demeaning gropes. It amounted to a nasty kind of ballet, and today Amelie was just slow enough that she was forced to dislodge Alberto with her elbow—which left him in a vengeful sulk throughout the dinner rush.

Amelie was philosophical about working at the Goodtime. It was not a prestigious restaurant, but it was not a dive, either; it was a working-class wine-and-beer establishment that had been in business for thirty-five years in this location and would probably be edged out before long by the rising rents—judging by the plague of croissant houses and sushi bars that had descended on the neighborhood. At the Goodtime, there was always a fish-and-chips lunch special. Fifteen tables and a few framed photographs of the Parthenon. The walls had recently been stuccoed.

Amelie had been working at the Goodtime for almost a year now and she had a kind of seniority, for what it was worth—the newer girls would come to her with questions. But seniority counted for shit. Seniority did not prevent the occurrence of truly rotten days.

Like today, when the new girl Tracy innocently grabbed off a couple of her regulars and seated them in her own section. Like today, when she was stiffed for a tip on a big meal. Like today, when some low-life picked a busy moment to walk out on his check—which George would sometimes forgive, but, of course, not today; today he docked her for the bill.

It was maybe not the worst day Amelie had ever experienced. That honor was held by the memorable occasion on which a female customer had come in during the afternoon, ordered the Soup of the Day, meticulously garnished the soup with crushed soda crackers, then retired to the Ladies and opened her wrists. Both wrists, thoroughly and fatally. Amelie had found her there.

George told her later that this had happened four times during the history of the Goodtime and that restaurant toilets were a popular place for suicides—strange as that seemed. Well, Amelie thought, maybe a suicide doesn’t want a cheerful place to die. Still, she could not imagine taking her final breath in one of those grim salmon-colored stalls.

So this was a bad day, but not the worst day—she was consoling herself with that thought—when Tracy tapped her shoulder and said there was a call for her on the pay phone.

Bad news in itself. No one was supposed to take calls on the pay phone. She could think of only one person who would call her here.

“Thanks,” she said, and delivered an order to Alberto, then checked to see if George was hanging around before she picked up the receiver.

It was Roch.

Her intuition had been correct:

Avery bad day.

He said, “You’re still working at that pit?”

“Listen,” Amelie said, “this is not a good time for me.”

“I haven’t called you for months.”

“You shouldn’t call me at work.”

“Then come by my place—when you get off tonight.”

“We don’t have anything to talk about.”

Amelie realized that her hand was cramping around the receiver, that both hands were sweaty, that her voice sounded high and throttled in her own ears.

Roch said, “Don’t be so shitty to your brother,” and she recognized the tone of offhanded belligerence that was always a kind of warning signal, a red flag. She heard herself become placating:

“It’s just—it’s like I said—a bad time. I can’t talk now. Call me at home, Roch, okay?”

“You’ll be home tonight?”

“Well—” She didn’t like the way he pounced on that. “I’m not sure—”

“What, you have plans?”

She took a deep breath. “I’m living with someone.”

“What? You’re doingwhat?” The outrage and the hurt in his voice made her feel a hot rush of guilt. Crazy, of course. Why should she consult him? But she hadn’t. And he was family.

But she could never have told him about Benjamin. She had been hoping—in a wistful, unconscious way—that the two of them would never have to meet.

The party at Table Four was signaling for her. This was, Amelie recognized, a truly shitty day.

She forced herself to say that she was living with a guy and that it might not be all right for Roch to come over, she just couldn’t say, maybe he ought to phone up first. There was a very long silence and then Roch’s voice became very sweet, very ingratiating: “All right, look—I just want you to be happy, okay?”

“I’m serious,” Amelie insisted.

“So am I. I’d like to meet this guy.”

“I don’t know if that’s a good idea.”

“Hey! I’ll be nice. What is it, you don’t trust me?”

“I just—well, call me, all right? Call me before you do anything.”

“Whatever you want.”

She waited until the line went dead, then stood with her forehead pressed against the cool glass of the enclosure. Took a breath, smoothed a wrinkle out of her uniform, forced herself to turn back toward the tables.

George was standing there—hands on his hips, a monumental frown. “You know you’re not supposed to use this phone.”

She managed, “I’m sorry.”

“By the way, the corner table? The party that was waiting for the bill? They had to leave.” Now George smiled. ” Tracy took your tip.”

* * *

She was out of the place by nine.

Nine o’clock on a Friday in October and Yonge Street was crowded with the usual … well, Amelie thought of them astypes. Street kids with leather jackets and weird haircuts. Blue-haired old ladies in miniskirts. Lots of the kind of lonely people you see scurrying past on nights like this, with no discernible destination but in a wild hurry to get there: heads down, shoulders up, mean and shy at the same time. It made her glad to have a home to head for, even if it was only a shitty apartment in St. Jamestown. Shitty but not, of course, cheap—nothing in this town was cheap.

She peered into the shop windows, trying to distract herself, but it was a chilly night and she felt intimidated by the warm glow of interiors and the orange light spilling out of bus windows as she trudged past the transit station. Nights like this had always seemed comfortless to her. You could smell winter gathering like an army just over the horizon. Nights like this, her thoughts ran in odd directions.

She thought about Roch, although she didn’t want to.

She thought about Benjamin.

Impossible to imagine the two of them together. They were so different … although (and here was the only similarity) each of them seemed to Amelie endlessly mysterious.

Roch should not have been a mystery. Roch, after all, was her brother. They shared family … if you could call it family, an absentee father and a mother who was arrested for shoplifting with such startling regularity that she had been banned from Eaton’s, Simpson’s, and Ogilvy’s. Sometimes Amelie felt as if she had been raised by a Social Welfare caseworker. She’d been fostered out twice. But the thing was, you learned to adapt.

Roch, her little brother, never did. They grew up in a rough part of Montreal and went to the kind of Catholic school where the nuns carried wooden rulers with metal edges embedded in them—in certain hands, a deadly weapon. The nuns were big on geometry and devotions. Amelie, however, had had her own agenda. In an era when the Parti Quebecois was dismantling English from the official culture, Amelie had resolved to teach herself the language. Not just the debased English everybody knew; not just the English you needed to follow a few American TV shows.Real English. She had conceived of a destiny outside Montreal. She saw herself living in English Canada, maybe eventually the States. Doing something glamorous—she wasn’t sure what. Maybe it would involve show business. Maybe she would manage a famous rock band.

Maybe she would wait tables.

Roch was different. He never had any ambitions that Amelie could figure out. When he was real little he would follow her around as singlemindedly as a duckling; she would tow him down St. Catherine’s Street on sunny summer days, buy Cokes and hot dogs and spend the afternoon watching the Types from the steps of Christ Church Cathedral.

Roch had needed the company. He never had friends. He took a long time learning to talk and he wasn’t reading with any facility until he was in fifth grade. Roch, it turned out, was slow. Not stupid—Amelie made this important distinction—just slow. When Roch learned something, he hung on to it fiercely. But he took his time. And in that school, in that place, taking your time was a bad thing. It made you look stupid. Not clever-stupid or sullen-stupid or anything dignified; it made you look dog-dumb, especially if you were also small and ugly and fat. Amelie had been bruised a few times defending Roch in the schoolyard. And that was when she bothered to stand up for him. A thirteen-year-old girl sometimes doesn’t want to know when her idiot brother is catching flack. She thought of him that way, too—her idiot brother—at least sometimes.

But Rochwasn’t stupid, Amelie knew, and he learned a lot.

He learned not to trust anybody. He learned that you could do what you wanted, if you were big enough and strong enough.

And he learned to get mad. He had a real talent for getting mad. Pointlessly, agonizingly mad; skin-tearing mad; going home and vomiting mad.

And then, eventually, he learned something else: he learned that if you grow up a little bit, and put on some muscle, then you can inspire fear in other people—and oh, what an intoxicating discovery that must have been.

Amelie trudged along Wellesley into St. Jamestown, past the hookers on the comer of Parliament, thinking October-night thoughts. She stopped at a convenience store to pick up a couple of TV dinners, the three-hundred-calorie kind. She was skinny—she knew it, in an offhand way—but her reflection in the shop windows always looked fat. Mama had been fat, with a kind of listless alcoholic fatness Amelie dreaded. Amelie was young and skinny and she meant to stay that way.

She put Roch out of her mind and thought about Benjamin instead, and that lightened her mood. She even managed a smile, standing at the check-out counter. Because Benjamin was the great discovery of her life.

A recent discovery.

He had come into the Goodtime just about six months ago, on one of those ugly spring days when the wind is raw and wet and just about anybody is liable to wander in off the street. She took him at first for one of those wanderers: a tall, benign-looking, shy man with a puppydog smile, his collar turned up and a black woolen cap plastered to his head. An oddball, but not a Type, exactly; he looked straight at her in a way Amelie appreciated. She remembered thinking the odds were mixed on somebody like that: he might tip generously or not at all … you could never tell.

But he did tip, and he came back the next day, and the day after that. Pretty soon he was one of her regulars. He came in late one Wednesday and she told him, “I’m going off-shift—you’re late,” and he said, “Well, I’ll walk you home,” in that straight-ahead way, and Amelie said that would be all right—she didn’t even have to think about it—and pretty soon they were seeing each other. Pretty soon after that he moved out of his basement room on Bathurst and into the St. Jamestown apartment.

Benjamin was decent, well-meaning, kind.

Roch enjoyed crushing people like that.

Amelie’s smile faded.

And of course there was the other problem, which she tried not to think about, because, even among these other mysteries, it wastoo mysterious, too strange.

The thing about Benjamin was, he wasn’t always Benjamin.

* * *

The apartment was a mess, but it felt warm and cozy when Amelie let herself in. She kicked off her shoes, ran some hot water for the dishes, plugged a Doors tape into the stereo.

She was not deeply into Sixties rock, but there was something about Morrison: he just never sounded old-fashioned. The tape wasStrangeDays; the song that came up was “People Are Strange.” Loping drumbeat and Ray Manzarek moaning away on keyboard. That real sparse guitar sound. And Morrison’s voice doing his usual psycho-sexy thing.

Timeless. But she turned it down a little when she peeked into the bedroom and saw Benjamin asleep under the covers. He slept odd hours; that was one of the strange things about him. But she doubted the tape would wake him—he slept like a slab of granite.

Back to the dishes, Amelie thought.

Awright, yeah! said Morrison.

And if Roch came by—

But maybe he wouldn’t. She consoled herself with that thought, bearing down with the scrub brush on one of the Chinese dragon bowls she’d bought in Chinatown. The basic fact about Roch was his unpredictability. He might say he was going to do something, but that didn’t mean shit. You never could tell.

She took some marginal comfort in these thoughts, losing herself in the rhythm of the music and the soapy smell of the hot water.

She was draining the sink when the last song, “The Music’s Over,” faded out. She heard the click of the tape as it switched off, the faint metallic transistor hiss from the speakers … and the knock at the door.

* * *

“You should have called.”

“I tried earlier. You weren’t home.” Roch stood blinking in the hallway. “You’re supposed to invite me in.”

Amelie stood aside as he came through the door.

“Place is a mess,” he observed.

“I just got home, all right?”

He shrugged and sat down.

It was six months since Amelie had seen her brother, but it was obvious he hadn’t let up on his gym work. He was six foot one, a head taller than Amelie, and his shoulders bulked out under his bomber jacket. AD the body work, however, had done nothing for his looks. His face was wide and pasty, his lips were broad. He stood with his hands in his jacket pockets and Amelie could see them moving there, knitting and unraveling, making fists, the fingernails digging into the palms. She told him to sit down.

He pushed aside a pile of newspapers and sprawled on the sofa.

Amelie made coffee and talked to him from the kitchen. There had been a letter from Montreal: Mama was adjusting to the new apartment even though it was smaller than the old one. Uncle Baptiste had been in town, looking for work when the Seaway trade picked up again. She kept her voice down, because it was possible even now that Benjamin might sleep through the whole thing … that Roch would say what he had to say and then leave. She pinned her hopes on that.